CHAPTER 24

Median Neuropathy

Definition

There are three general areas in which the median nerve can become entrapped around the elbow and forearm. Because this chapter mainly deals with entrapment below the elbow and above the wrist, the most proximal and least frequent entrapment is not discussed but merely mentioned. Elbow median nerve entrapment is the compression of the nerve by a dense band of connective tissue called the ligament of Struthers, an aberrant ligament found immediately above the elbow. The topics discussed in this chapter are compression of the median nerve at or immediately below the elbow, where the pronator teres muscle compresses it, and compression distally of a branch of the median nerve—the anterior interosseous nerve.

Increased risk for pronator syndrome may be associated with individuals involved in repetitive elbow, wrist, and hand movements, such as chopping wood, playing racket sports, rowing, weightlifting, and throwing. However, pronator syndrome is four times more likely to affect women than men, suggesting that the dominant risk factor is an anatomic anomaly (structural variation) and not overuse. The dominant arm is most likely to be affected, particularly if the individual is heavily muscled (muscle hypertrophy). Pronator syndrome is most commonly diagnosed in individuals between the ages of 40 and 50 years [1]. Pronator syndrome is rare but is the second most common cause of medial nerve compression after carpal tunnel syndrome. Pronator syndrome is responsible for less than 1% of all median nerve entrapment disorders [2]. Anterior interosseous syndrome has a similar 1% occurrence rate in median nerve entrapment disorders [3].

Pronator Teres Syndrome

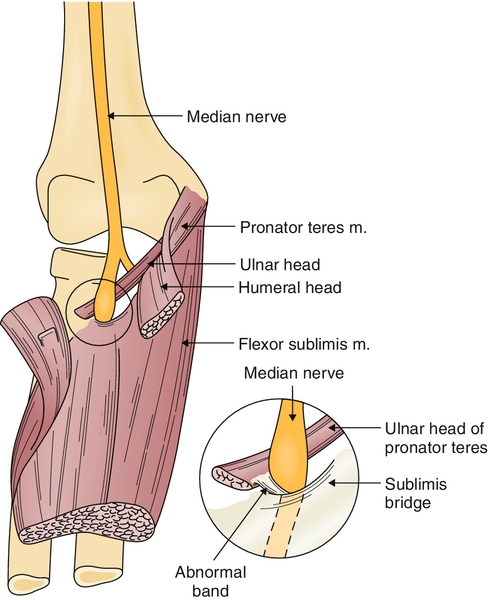

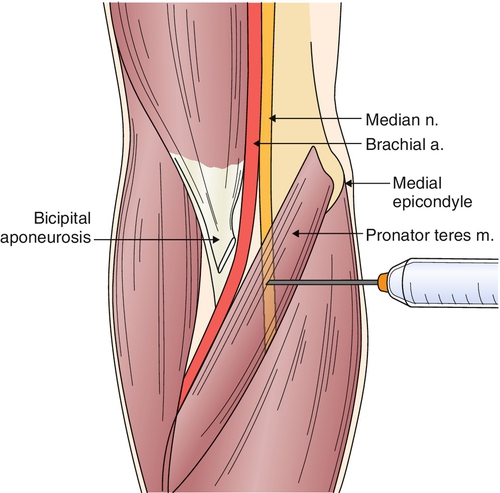

Pronator teres syndrome [4,5] is a symptom complex that is produced where the median nerve crosses the elbow and becomes entrapped as it passes first beneath the lacertus fibrosus—a thick fascial band extending from the biceps tendon to the forearm fascia—then between the two heads (superficial and deep) of the pronator teres muscle and under the edge of the flexor digitorum sublimis (Fig. 24.1). Compression may be related to a local process, such as pronator teres hypertrophy, tenosynovitis, muscle hemorrhage, fascial tear, postoperative scarring, anomalous median artery, or giant lipoma. The median nerve may also be injured by occupational strain, such as carrying a grocery bag or guitar playing, and by insertion of a catheter [4–13].

Anterior Interosseous Syndrome

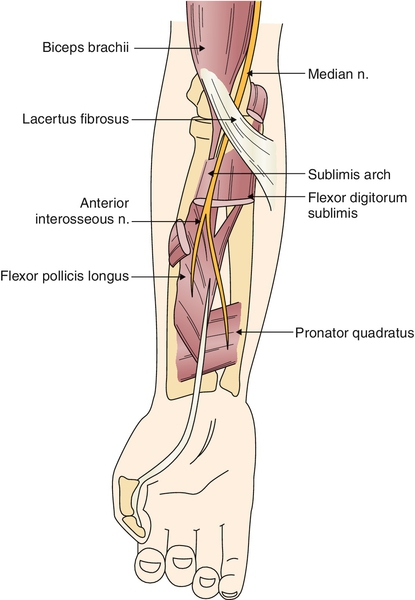

The anterior interosseous nerve arises from the median nerve 5 to 8 cm distal to the lateral epicondyle [4,6,14]. Slightly distal to its course through the pronator teres muscle, the median nerve gives off the anterior interosseous nerve, a purely motor branch (Fig. 24.2). It contains no fibers of superficial sensation but does supply deep pain and proprioception to some deep tissues, including the wrist joint. This nerve may be damaged by direct trauma, forearm fractures, humeral fracture, injection into or blood drawing from the cubital vein, supracondylar fracture, and fibrous bands related to the flexor digitorum sublimis and flexor digitorum profundus muscles. In some patients, it is a component of brachial amyotrophy of the shoulder girdle (proximal fascicular lesion) or related to cytomegalovirus infection or a bronchogenic carcinoma metastasis. The nerve may be partially involved, but in a fully established syndrome, three muscles are weak: flexor pollicis longus, flexor digitorum profundus to the second and sometimes the third digit, and pronator quadratus [4,6,12–18].

Symptoms

Pronator Teres Syndrome

In an acute compression, with unmistakable symptoms, the diagnosis is relatively simple to establish [5,14]. In many cases of intermittent, mild, or partial compression, the signs and symptoms are vague and nondescript. The most common symptom is mild to moderate aching pain in the proximal forearm, sometimes described as tiredness and heaviness. Use of the arm may cause a mild or dull aching pain to become deep or sharp. Repetitive elbow motions are likely to provoke symptoms. As the pain intensifies, it may radiate proximally to the elbow or even to the shoulder. Paresthesias in the distribution of the median nerve may be reported, but they are generally not as severe or well localized as the complaints in carpal tunnel syndrome. When numbness is a prominent symptom, the complaints may mimic carpal tunnel syndrome. However, unlike carpal tunnel syndrome, pronator teres syndrome rarely has nocturnal exacerbation, and the symptoms are not affected by a change of wrist position.

Anterior Interosseous Syndrome

The onset of anterior interosseous syndrome can be related to exertion, or it may be spontaneous. In classic cases of spontaneous anterior interosseous nerve paralysis, there is acute pain in the proximal forearm or arm lasting for hours or days. There may be a history of local trauma or heavy muscle exertion at the onset of pain. As mentioned, the patient may complain of weakness of the forearm muscles innervated by the anterior interosseous nerve. Theoretically, there should be no sensory complaints [6].

Physical Examination

Pronator Teres Syndrome

Findings may be ill-defined and difficult to substantiate in pronator teres syndrome [5,14]. The most important physical finding is tenderness over the proximal forearm. Pressure over the pronator teres muscle produces discomfort and may produce a radiating pain and digital numbness. The symptomatic pronator teres muscle may be firm to palpation compared with the other side. The contour of the forearm may be depressed, caused by the thickening of the lacertus fibrosus. Distinctive findings are weakness of both the intrinsic muscles of the hand supplied by the median nerve and the muscles proximal to the wrist and in the forearm with tenderness, Tinel sign over the point of entrapment, and absence of Phalen sign. Pain may be elicited by pronation of the forearm, elbow flexion, or even contraction of the superficial flexor of the second digit. Sensory examination findings are usually poorly defined but may involve not only the median nerve distribution of the digits but also the thenar region of the palm because of involvement of the palmar cutaneous branch of the median nerve. Deep tendon reflexes and cervical examination findings should be normal [7,12,13,15–19].

Anterior Interosseous Syndrome

To test the muscles that the anterior interosseous nerve innervates [5,14], the clinician braces the metacarpophalangeal joint of the index finger and the patient is asked to flex only the distal phalanx. This isolates the action of the flexor digitorum profundus on the terminal phalanx and eliminates the action of the flexor digitorum superficialis. There is no terminal phalanx flexion if the anterior interosseous nerve is injured.

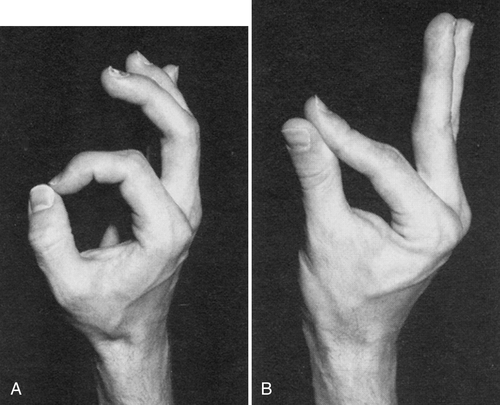

Another useful test is to ask the patient to make the “OK” sign [20]. In anterior interosseous syndrome, the distal interphalangeal joint cannot be flexed, and this results in the index finger’s remaining relatively straight during this test (Fig. 24.3). The patient is asked to forcefully approximate the finger pulps of the first and second digits. The patient with weakness of the flexor pollicis longus and digitorum profundus muscles cannot touch with the pulp of the fingers, but rather the entire volar surfaces of the digits are in contact. This is due to the paralysis of the flexor pollicis longus and flexor digitorum profundus of the second digit. The pronator quadratus is difficult to isolate clinically, but an attempt can be made by flexing the forearm and asking the patient to resist supination. Sensation and deep tendon reflexes should be normal [7,12,13,15–19].

Functional Limitations

Pronator Teres Syndrome

In pronator teres syndrome, there is clumsiness, loss of dexterity, and a feeling of weakness in the hand. This may lead to functional limitations both at home and at work. Repetitive elbow motions, such as hammering, cleaning fish, serving tennis balls, and rowing, are most likely to provoke symptoms.

Anterior Interosseous Syndrome

As weakness develops in anterior interosseous syndrome, there is loss of dexterity and pinching motion with difficulty in picking up small objects with the first two digits. Activities of daily living, such as buttoning shirts and tying shoelaces, can be impaired. Patients may have difficulty with typing, handwriting, cooking, and so on.

Diagnostic Studies

Pronator Teres Syndrome

Electrodiagnostic testing (nerve conduction studies and electromyography) is the “gold standard” for confirming pronator teres syndrome [4,21,22]. Results of nerve conduction studies may be abnormal in the median nerve distribution; however, the diagnosis may be best established by electromyographic studies demonstrating membrane instability (including increased insertional activity, fibrillation and positive sharp waves at rest, wide and high amplitude polyphasics on minimal contraction, and decreased recruitment pattern on maximal contraction) of the median nerve muscles below and above the wrist in the forearm but with sparing of the pronator teres [22,23]. Imaging studies (e.g., radiography, computed tomography, hypoechoic swelling by ultrasonography, and magnetic resonance imaging) are used to exclude alternative diagnoses. Magnetic resonance imaging and high-resolution ultrasonography may be helpful in diagnosis, although there is no consensus on which is the preferred method [24–29].

Anterior Interosseous Syndrome

Electrodiagnostic studies may also help establish the diagnosis of anterior interosseous syndrome [5]. In general, the results of routine motor and sensory studies are normal. The most appropriate technique is surface electrode recording from the pronator quadratus muscle with median nerve stimulation at the antecubital fossa. On electromyography, findings of membrane instability are restricted to the flexor pollicis longus, flexor digitorum profundus (of the second and third digits), and pronator quadratus [9,21].

Imaging studies are useful in excluding other diagnoses. [25–29]

Treatment

Initial

Pronator Teres Syndrome

Treatment is initially conservative, with rest and avoidance of the offending repetitive trauma [6,14]. A wrist immobilization splint is applied in 15 degrees of dorsiflexion for 4 to 6 weeks. The patient is instructed in friction massage. Ice and electrical stimulation are instituted three times a week for 10 treatments. The splint is discontinued at a time determined by the physician [30]. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs may help with pain and inflammation. Analgesics may be used for pain. Low-dose tricyclic antidepressants may be used for pain and to help with sleep. Antiseizure medications are also often used for neuropathic pain (e.g., carbamazepine, gabapentin).

Anterior Interosseous Syndrome

Treatment of the anterior interosseous syndrome depends on the cause [5,14]. Penetrating wounds require immediate exploration and repair. Impending Volkmann contracture demands immediate decompression. In spontaneous cases associated with specific occupations, a trial of nonoperative therapy is indicated. If spontaneous improvement does not occur by 6 to 8 weeks, consideration should be given to surgical exploration. Conservative management includes avoiding the activity that exacerbates the symptoms. Pharmacologic treatment is similar to that for pronator teres syndrome.

Rehabilitation

Pronator Teres Syndrome

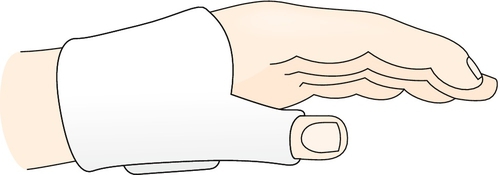

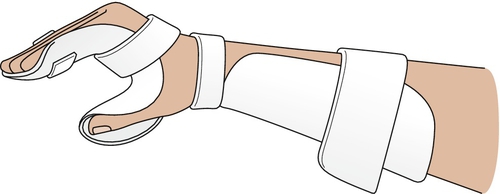

A splint that can put the thumb in an abducted, opposed position, such as a C bar or a thumb post–static orthosis, can be used (Fig. 24.4) [8,9,11]. Taping of the index and middle fingers in a buddy splint to stabilize the lack of distal interphalangeal flexion may be helpful [11].

Rehabilitation may include modalities such as ultrasound, electrical stimulation, iontophoresis, and phonophoresis. The patient can be instructed in ice massage as well. Once the acute symptoms have subsided, physical or occupational therapy can focus on exercises to improve forearm flexibility, muscle strength responsible for thumb abduction, opposition, and wrist radial flexion.

Anterior Interosseous Syndrome

Resting the arm by immobilization in a splint may be tried (Fig. 24.5) [31]. If the symptoms subside, conservative physical or occupational therapy, including physical modalities as previously described and exercises to improve strength and function of the pronator quadratus, flexor digitorum profundus, and flexor pollicis longus, can be initiated [11].

Procedures

In both anterior interosseous and pronator teres syndromes, a median nerve block may be attempted [32] (Figs. 24.6 and 24.7).

Surgery

Pronator Teres Syndrome

If symptoms fail to resolve, surgical release of the pronator teres muscle and any constricting bands (ligament of Struthers and lacertus fibrosus) should be considered with direct exploration of the area. Traditionally, an S-shaped incision is typically used to extensively expose the entire median nerve from the forearm to the hand [33]. Recent techniques have elucidated the possible advantage of using small-incision endoscopic procedures [34,35].

Anterior Interosseous Syndrome

If spontaneous improvement does not occur by 6 to 8 weeks, consideration should be given to surgical exploration. The surgical technique for exploration is exposure of the median nerve directly beneath the pronator teres or separation of this muscle from the flexor carpi radialis, identification of the anterior interosseous nerve, and release of the offending structures.

If surgical decompression was performed and failed to resolve the weakness, tendon transfers may be considered after a more proximal fascicular lesion is ruled out [33]. Endoscopically assisted technique has been tried but without much success at this point because of the depth of the surgical approach and limited view [36].

Postoperative Rehabilitation [30]

0 to 1 week

Postoperative dressing is removed. Active and gentle passive range of motion exercises are initiated for 15 minutes per hour. Desensitization and edema management are instituted. Pronation and elbow extension stretching exercises are instituted four times a day.

3 weeks

Strengthening is initiated in accordance with the patient’s comfort level using putty, Hand Helper, and Thera-Band.

Potential Disease Complications

Pronator Teres Syndrome

Disease-related complications, if the condition is left unresolved, include permanent loss of the use of the pinch grasp, lack of wrist flexion, and incessant pain.

Anterior Interosseous Syndrome

If it is allowed to persist, this syndrome will cause inability to perform the pinch grasp, resulting in the functional deficits mentioned before.

Potential Treatment Complications

Use of anti-inflammatory medications such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs can induce gastric, renal, and hepatic side effects. Local steroid injections can induce skin depigmentation, local atrophy, or infection. Surgical complications include infection, bleeding, and injury to surrounding structures.