CHAPTER 22. LOCAL ANAESTHETICS

Indications180

Dosage180

Complications – lidocaine toxicity180

Contraindications181

Practical procedure181

Sigmund Freud was aware of the analgesic properties of cocaine, but its anaesthetic properties were recognized by his colleague, the Austrian ophthalmologist Karl Koller (1857–1944). He successfully performed eye surgery utilizing the local anaesthetic properties of cocaine in 1884, a significant breakthrough in the developing field of anaesthesia.

INTRODUCTION

Local anaesthetic agents have varying onset times, duration of action and ability to penetrate tissue. Chemically they are separated into esters (cocaine, procaine, amethocaine) and amides (lidocaine, prilocaine, bupivacaine), which is relevant to their metabolism and tendency to toxicity. Esters are rapidly metabolized by serum and liver cholinesterase and therefore metabolism is retarded by low enzyme levels such as pregnancy or liver disease. Amides are metabolized by liver microsomal enzymes, which may be less effective when hepatic function or blood flow are reduced.

Local anaesthetics work by reversibly blocking conduction along nerve fibres through binding to voltage-gated sodium channels in the neuronal membrane. This prevents sodium ion entry during depolarization, which in turn prevents the propagation of the action potential. The membrane in effect becomes stabilized. Consequently, the response to painful stimuli is not effected and pain is not sensed centrally.

Local anaesthetics are weak bases and are most efficacious in alkaline conditions, whereby the un-ionized form crosses the neuronal membrane. Conversely, infected or inflamed tissues have an acidic environment, which reduces the action of local anaesthetics. Furthermore, the increased vascularity of these environments gives rise to an increased risk of systemic absorption and subsequent side-effects. Local anaesthetics affect the smaller nerves such as the autonomic before the medium-sized sensory and large motor nerves. They are more effective at higher concentrations, having a shorter onset and longer duration. The duration of local anaesthetics is prolonged when combined with vasoconstrictors such as weak epinephrine solutions (e.g. 1 in 200, 000).

INDICATIONS

These anaesthetics provide local anaesthesia for painful procedures. The most commonly used local anaesthetic for ward-based procedures is lidocaine (also known as lignocaine). Various lidocaine preparations are available:

• Topical cream – anaesthesia before minor skin procedures, e.g. cannulation.

• Topical gel – e.g. catheterization.

• Injection – e.g. central line insertion, chest and ascitic drain insertion, lumbar puncture, suturing.

• Injection in combination with epinephrine prolongs the local anaesthetic effect by reducing blood flow and thus the rate of systemic absorption. However, this is usually required in specialist circumstances such as facial or scalp anaesthesia, and is not recommended for use in the procedures described in this book.

DOSAGE

The concentration of lidocaine (mg/mL) equals the percentage concentration multiplied by 10. For example:

• 1% lidocaine = 10 mg/mL.

• 2% lidocaine = 20 mg/mL.

The maximum dose of lidocaine (without vasoconstrictor agent) can be calculated as follows:

• For example, for an individual weighing:

Tip Box

Tip Box

The British National Formulary (BNF) recommends to reduce the dose in elderly or debilitated patients when using local anaesthetics.

COMPLICATIONS – LIDOCAINE TOXICITY

The membrane-stabilizing effects of local anaesthetics can become excessive if plasma concentrations become elevated. This leads to toxic effects, particularly affecting neural and cardiovascular tissues. The permitted dosage should therefore be strictly adhered to.

• Arterial plasma concentrations of local anaesthetic (through local absorption and uptake into the systemic circulation) peak within about 10–30 minutes. Toxic effects are most likely to manifest during this period.

• Initial side-effects include a feeling of ‘light-headedness’, circumoral paraesthesia, visual disturbances and twitching.

• More severe toxic effects include convulsions, cardiac arrhythmias and cardiovascular collapse. These can occur rapidly upon inadvertent intravascular administration.

• The management of these toxic effects would be in accordance with the Resuscitation Council (UK) guidelines for adult advanced life support (ALS).

• Intravenous benzodiazepines not only have a role in seizure termination but also in raising seizure threshold. They should therefore be considered in the prevention of seizures when frequent twitching is observed.

Tip Box

Tip Box

The British National Formulary (BNF) recommends that when using local anaesthetics ‘resuscitative equipment should be available’.

CONTRAINDICATIONS

• Complete heart block.

• Certain arrhythmogenic cardiological conditions are exacerbated by local anaesthetics (e.g. bupivacaine in Brugada syndrome). Consult with a specialist before using local anaesthetics in these patients.

• Hypovolaemia.

• Known allergy to lidocaine (rare).

• Local anaesthetic in combination with epinephrine should NEVER be used in digits and appendages given the consequent risk of ischaemic necrosis.

PRACTICAL PROCEDURE

FIELD BLOCK

This is used for anaesthesia of small cutaneous nerves.

Tip Box

Tip Box

Initial subcutaneous infiltration of local anaesthetic gives rise to a small wheal or bleb, which commonly distorts the anatomical landmarks at the site of the intended procedure. It is therefore useful to mark such landmarks with a skin pen prior to infiltration.

• Ask an assistant to show you the vial of local anaesthetic prior to drawing it up. Check the date, concentration and drug name on the vial.

• To maintain aseptic technique, the assistant opens the vial of local anaesthetic and offers it to the operator’s needle.

• Attach a small-calibre needle (such as an orange needle) to the syringe for initial skin and subcutaneous infiltration.

• Warn the patient of a sharp scratch and a subsequent stinging sensation prior to administration.

• Take care to avoid accidental intravascular injection: ALWAYS draw back on the syringe prior to infiltrating.

• Infiltrate deeper tissues with a green needle.

Tip Box

Tip Box

Allow a few minutes for subcutaneous anaesthesia to take effect, then ensure adequate anaesthesia by testing for sensation with either ethyl chloride spray or a needle tip prior to performing the intended procedure.

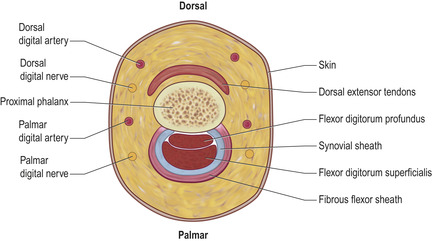

DIGITAL BLOCK

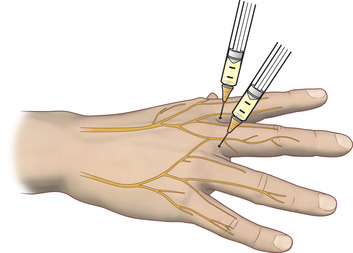

Each digit is innervated by two dorsal and two ventral nerve branches (Fig. 22.1). Anaesthesia of a digit (e.g. prior to cleaning a digital wound or manipulating a digital fracture) can be performed either by a ring block or a tendon (transthecal) block.

|

| Fig. 22.1 |

RING BLOCK

• Position the patient’s hand with fingers extended and abducted.

• Insert the needle into the dorsolateral aspect of the digit at the level of the base of the metacarpal bone and administer approximately 1 mL of 1% lidocaine local anaesthetic (Fig. 22.2).

• Repeat this procedure at the same point on the opposite side of the digit.

• Wait a few minutes to allow the local anaesthetic to diffuse through the subcutaneous tissue and infiltrate the dorsal and ventral nerve branches.

TENDON (TRANSTHECAL) BLOCk

In tendon block local anaesthetic is infused along the flexor tendon sheath.

• Inject between 2–3 mL of 1% lidocaine into the flexor tendon at the base of the digit (Fig. 22.3).