CHAPTER 22

Lateral Epicondylitis

Definition

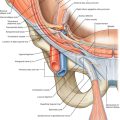

Epicondylitis is a general term used to describe inflammation, pain, or tenderness in the region of the medial or lateral epicondyle of the humerus. The actual nidus of pain and pathologic change has been debated. Lateral epicondylitis implies an inflammatory lesion with degeneration at the tendinous origin of the extensor muscles (the lateral epicondyle of the humerus). The tendon of the extensor carpi radialis brevis muscle is primarily affected. Other muscles that can contribute to the condition are the extensor carpi radialis longus and the extensor digitorum communis.

Although the term epicondylitis implies an inflammatory process, inflammatory cells are not identified histologically. Instead, the condition may be secondary to failure of the musculotendinous attachment with resultant fibroplasia [2], termed tendinosis. Other postulated primary lesions include angiofibroblastic tendinosis, periostitis, and enthesitis [3]. Overall, the focus of injury appears to be the common extensor tendon origin. Symptoms may be related to failure of the repair process [4].

Repetitive stress has been implicated as a factor in this condition [5]. Overuse from a tennis backhand (especially a one-handed backhand with poor technique) can frequently lead to lateral epicondylitis (hence, the term tennis elbow is frequently used synonymously with lateral epicondylitis, regardless of its etiology). Repetitive computer use (especially with a mouse) as well as golf, swimming, and baseball can cause or exacerbate epicondylitis.

Symptoms

Patients usually report pain in the area just distal to the lateral epicondyle. The patient may complain of pain radiating proximally or distally. Patients may also complain of pain with wrist or hand movement, such as gripping a doorknob, carrying a briefcase, or shaking hands. Patients occasionally report swelling as well.

Physical Examination

On examination, the hallmark of epicondylitis is tenderness over the extensor muscle origin. The common origin of the extensor muscles can be located one fingerbreadth below the lateral epicondyle. With lateral epicondylitis, pain is increased with resisted wrist extension, especially with the elbow extended, the forearm pronated, the wrist radially deviated, and the hand in a fist. The middle finger test can also be used to assess for lateral epicondylitis. Here, the proximal interphalangeal joint of the long finger is resisted in extension, and pain is elicited over the lateral epicondyle. Swelling is occasionally present. In cases of recalcitrant lateral epicondylitis, the diagnosis of radial nerve entrapment should be considered. The radial nerve can become entrapped just distal to the lateral epicondyle where the nerve pierces the intermuscular septum (between the brachialis and brachioradialis muscles). There may be localized tenderness along the course of the radial nerve around the radial head. Motor and sensory findings are usually absent.

Functional Limitations

The patient may complain of an inability to lift or to carry objects on the affected side secondary to increased pain. Typing, using a computer mouse, or working on a keyboard may re-create the pain. Even handshaking or squeezing may be painful in lateral epicondylitis. Athletic activities may cause pain, especially with an acute increase in repetition, poor technique, and equipment changes (frequently with a new racket or stringing).

Diagnostic Studies

The diagnosis is usually made on clinical grounds. Magnetic resonance imaging, which is particularly useful for soft tissue definition, can be used to assess for tendinitis, tendinosis, degeneration, partial tears or complete tears, and detachment of the common extensor tendons at the lateral epicondyle [6]. Magnetic resonance imaging is rarely needed, however, except in recalcitrant epicondylitis, and it will not alter the treatment significantly in the early stages. The lateral collateral ligament complexes can be evaluated for tears as well as for chronic degeneration and scarring. Ultrasonography has been used to diagnose lateral epicondylitis [7]. Arthrography may be beneficial if capsular defects and associated ligament injuries are suspected. Barring evidence of trauma, early radiographs are of little help in this condition but may be useful in cases of resistant tendinitis and to rule out occult fractures, arthritis, and an osteochondral loose body.

Treatment

Initial

Initial treatment consists of relative rest, avoidance of repetitive motions involving the wrist, activity modification to avoid stress on the epicondyle, anti-inflammatory medications, and thermal modalities such as heat and ice for acute pain. Patients who develop lateral epicondylitis from tennis should modify their stroke (especially improving the backhand stroke to ensure that the forearm is in midpronation and the trunk is leaning forward) and their equipment, usually by reducing string tension and enlarging the grip size [5]. Frequently, a two-handed backhand will relieve the stress sufficiently.

In addition, a forearm band (counterforce brace) worn distal to the extensor muscle group origin can be beneficial (Fig. 22.1). The theory behind this device is that it will dissipate forces over a larger area of tissue than the lateral attachment site. Alternatively, the use of wrist immobilization splints may be helpful. A splint set in neutral can be helpful for lateral epicondylitis by relieving the tension on the flexors and extensors of the wrist and fingers. A splint set in 30 to 40 degrees of wrist extension will relieve the tension on the extensor tendons, including the extensor carpi radialis brevis muscle as well as other wrist and finger extensors [13,14]. Dynamic extension bracing has also been proposed [15].

Rehabilitation

Rehabilitation may include physical or occupational therapy. Therapy should include two phases. The first phase is directed at decreasing pain by physical modalities (ultrasound, electrical stimulation, phonophoresis, cortisone iontophoresis [16], myofascial release [17], heat, ice, massage) and decreasing disability (education, reduction of repetitive stress, and preservation of motion). When the patient is pain free, a gradual program is implemented to improve strength and endurance of wrist extensors and stretching. This program must be carefully monitored to permit strengthening of the muscles and work hardening of the tissues without itself causing an overuse situation. The patient should start with static exercises and advance to progressive resistive exercises (with an emphasis on the eccentric phase of the exercise). Thera-Band, light weights, and manual (self) resistance exercises can be used.

Work or activity restrictions or modifications may be required for a time.

Procedures

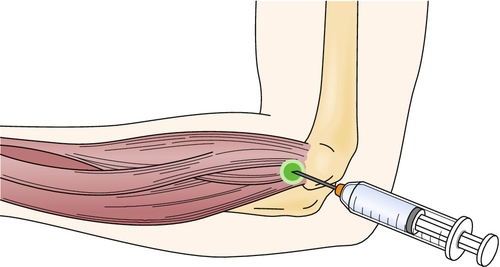

Injection of corticosteroid, usually with a local anesthetic, into the area of maximum tenderness (approximately 1 to 5 cm distal to the lateral epicondyle) has been shown to be effective in treatment of lateral epicondylitis (Fig. 22.2) [18]. To confirm the diagnosis, a trial of lidocaine alone may be given. An immediate improvement in grip strength should be noted after injection. Postinjection treatment includes icing of the affected area both immediately (for 5 to 10 minutes) and thereafter (a reasonable regimen is 20 minutes two or three times per day for 2 weeks) and wearing of a wrist splint (particularly for activities that involve wrist movement). The wrist splint should be set in slight extension for lateral epicondylitis. Exacerbating activities are to be avoided. Platelet-rich plasma injections have been shown to reduce pain and to increase function in patients with lateral epicondylitis [19–21]. Injection of botulinum toxin into the extensor digitorum communis muscles to the third and fourth digits has been reported to be beneficial in chronic treatment–resistant lateral epicondylitis [22,23].

There are studies that support acupuncture as an effective modality in the short-term relief of lateral epicondylitis [24–26]. Extracorporeal shock wave treatment may also be beneficial in lateral epicondylitis [27].

Surgery

Surgery may be indicated in those patients with continued severe symptoms who do not respond to conservative management. For lateral epicondylitis, surgery is aimed at excision and revitalization of the pathologic tissue in the extensor carpi radialis brevis and release of the muscle origin [28]. Pinning may be done if the elbow joint is unstable [29].

Potential Disease Complications

Possible long-term complications of untreated epicondylitis include chronic pain, loss of function, and possible elbow contracture. In general, epicondylitis is more easily and successfully treated in the acute phase.

Potential Treatment Complications

Analgesics and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs have well-known side effects that most commonly affect the gastric, hepatic, and renal systems. Local steroid injections may increase the risk for disruption of tissue planes, create high-pressure tissue necrosis, rupture tendons [1], damage nerves, promote skin depigmentation or atrophy, or cause infection [30].