international environmental health initiatives designed for developing country contexts provide some pointers to addressing the problems of unsanitary living environments and poor hygiene in remote Australian Indigenous communities.

ABORIGINAL AND TORRES STRAIT ISLANDER POLICIES

Extreme levels of disadvantage

Many Aboriginal people living in the Northern Territory (NT) experience extreme disadvantage. The key underlying causes for this disadvantage are social inequality and powerlessness, with these factors impacting negatively on their health and wellbeing (Devitt et al. 2001, House of Representatives Standing Committee on Family and Community Affairs 2000). The social inequality they experience is due to events of history and successive federal, state and territory government policies. Conflict and power are intrinsic elements in all policy decision making (Oliver 2006), but nowhere is this more apparent than in past and current policies that focus on Indigenous affairs. Many of these policies have been described by Aboriginal leaders as leading to a cycle of grief, anger and despair in the lives of Aboriginal people (Aboriginal Medical Services Alliance of the NT [AMSANT] 2000).

A historical perspective

The history of poor treatment of Aboriginal people by governments commenced with the declaration of terra nullius by the colonisers of Australia in 1788. This declaration reflected a perception by government of Aboriginal Australians being inferior and having no rights, and placed Aboriginal people at the mercy of the colonisers. Devitt et al. (2001 p 13) described how this unfolded in the NT:

Losing control of their lands resulted in the loss of their economic base; this was frequently accomplished in an ethos of gross personal violence, brutality and family dislocation. In the NT, it continued well into the lifetimes of contemporary Aboriginal people. Communities of hunters and gatherers became either a convenient workforce for the settlers within the economic system they hastened to establish or unwanted nuisances to be ignored, regulated, and moved on or, at times, exterminated.

It was not until 1967, in response to increasing political pressure that the Commonwealth government agreed to conduct a referendum to decide if discriminatory clauses concerning Aboriginal people should be removed from the Constitution. The overwhelming ‘yes’ vote of the referendum was interpreted as expressing a public desire that the Commonwealth should act decisively to resolve all problems concerning Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples’ rights. However, in the ensuing years, the political imperative for the Commonwealth Government to take action lost impetus and the situation stayed much the same (Long 2000).

In 1972, with a change in government, Aboriginal affairs again became a topical issue. Whitlam (1973), in a statement provided at a conference of Commonwealth and state ministers concerned with Aboriginal affairs wrote:

That my government intends therefore to assume full responsibility for policy and finance in respect of Aboriginal Affairs and will take any necessary legislative action to this end.

From this time, the Commonwealth (the Australian or federal government) has lead and coordinated policy initiatives concerning Indigenous affairs across the states and territories. In the same statement, the new government announced that its aim was:

… to restore to the Aboriginal people of Australia their lost power of self determination in economic, social and political affairs.

This announcement marked the era of policy approaches that included the concepts ‘self-determination’ and ‘community control’. Still some states resisted giving Aboriginal communities control of their own affairs. Consequently, the Commonwealth introduced legislation to enable Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities to incorporate so government initiatives could be progressed. Newly formed Indigenous community councils and housing associations were quick to accept responsibility for delivering housing and water and sanitation services in their communities (Long 2000). Few communities had the capacity to assume responsibility for these services.

Health, housing and environmental health policy

Policies to address the poor health and living conditions of Indigenous peoples have been described as confusing, disappointing, reactive, ad hoc, and with single strategies used to address the mix of social, cultural, political and economic factors that underlie problems (Coombs 1978, National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Council [NATSIHC] 2003, Tatz 1974). Environmental health policy initiatives in remote communities have focused on providing technologies and infrastructure such as water, sanitation and housing. The newly constructed houses mostly consisted of three bedrooms, one bathroom and toilet, kitchen and living area. In the rush to construct new dwellings, issues of maintenance of health hardware and the need to adapt living practices for this new environment received only hasty consideration. Few people had insight into the potential problems that might arise (Long 2000). The rapid introduction of new technology, crowding, and problems caused by a failure to change behaviours to suit the new housing environment, lead to another layer of complexity when trying to prevent infection and improve child health. One observer reported that education was either not provided when household latrines were introduced into communities, or inappropriately provided (Tatz 1974). Little emphasis was placed on, and few resources were provided for, increasing community capacity and establishing effective administrative systems. The governance arrangements for Indigenous housing have been fragmented and unstable since Indigenous Community Controlled Housing Organisations (ICCHOs) were first established (Bailie & Wayte 2006).

Health policies have largely focused on the treatment or eradication of diseases by the use of vaccines and improved medical management. To date, there have been no comprehensive, long-term policies to try to address the problem of the poor growth and development of Aboriginal children. In health and other policy areas, prevention activities have received little attention, generally only mentioned as a secondary issue. Governments have tried to address some housing problems by funding community-based programs to teach families how best to use, care and maintain their new homes. However, the primary aim of many of these programs appears to be prolonging the lifespan of housing infrastructure rather than promoting safe hygiene practices and health improvement. In some communities, government-employed environmental health officers ‘hand over’ new houses to families.

Governments have predominantly employed short-term approaches to address the complex issues that underlie poor hygiene and living conditions in remote communities. This ‘short-termism’ appears to be a response to the political imperatives of new governments, new ministers and lobbyists. There has been little research concerning the causes of poor hygiene, housing and poor environmental health conditions in Australian Indigenous contexts. There has been no systematic approach to learning from the failures and successes of past policy and program initiatives. However, there is much to be gained from reflecting on the history of policy, the development of community infrastructure and epidemiological patterns of child health in addition to drawing on lessons learnt from the introduction of water and sanitation technology to communities in developing countries and other disadvantaged settings. In those communities, as in remote Aboriginal communities, providing water and sanitation technology has not automatically lead to the behaviour change associated with good hygiene. This problem is attributed to the failure to recognise that the technology introduced into disadvantaged communities needs to fit comfortably with the values, practices and beliefs of individuals and the communal group (Hubley 1993). Further, for technology to bring health benefits, appropriate hygiene behaviours need to be adopted and sustained by a large proportion of the community (Bateman & Smith 1991).

The National Environmental Health Strategy (Department of Health and Aged Care 1999) states that families, communities and governments need to protect their children from environmental contamination. In view of the poor living conditions and poor health experienced by Indigenous children living in remote communities, it would appear that a succession of federal and territory governments have chosen not to uphold generally well recognised public health standards in these communities. There are several possible reasons for this:

Hence, the situation remains today that poor living conditions and poor personal and domestic hygiene in remote Aboriginal communities is a major public health problem severely affecting the health and wellbeing of children in these communities (Coates et al. 2002, Currie 2002, Gracey 1998, White et al. 2001). In Box 22.1, by way of a case study, we describe the living conditions of young children in one remote NT community. There is a general consensus that preventing infection in the household and community is a health priority for Australian Indigenous children living in remote communities (Chang et al. 2002, Coates et al. 2002, Currie 2002, Gracey 1998, White et al. 2001). However, despite the rhetoric around the need to protect the health of these children it does not often translate into meaningful action (Department of Health and Aged Care 1999). Past government approaches to policy and program development to address Indigenous health and wellbeing is captured in this statement published in The National Aboriginal Health Strategy (NATSIHC 1989 p xi):

Aboriginal people often feel that the motivation for government action in Aboriginal health comes as a response to intermittent political pressure, rather than from a commitment to effective long-term solutions for future generations. The art of the ‘quick fix’ seems to be the norm. Expedient gestures for Aboriginal problems are made by government and any commitment lasts only until media attention has eased or until the next election.

BOX 22.1 CASE STUDY

Threats to health from the environment in which children live

Our case study into the mechanisms by which poor living conditions and poor hygiene pose a threat to the health of young children in a remote Indigenous community setting in the Top End (McDonald 2007) involved literature reviews, a housing infrastructure survey, focus groups, and child carer and key informant interviews. Our investigations focused on why in many instances the hygiene needs of young children are not appropriately met. Our findings confirmed that the condition of some houses in which young children live present a serious threat to the health and wellbeing of occupants, especially to the health of young children. This assessment was based on the high rates of non-functioning essential items of housing infrastructure; the number of houses where contaminated matter was observed in the living environment; and levels of household crowding.

All the items considered necessary to enable essential hygiene practice and assist meeting the nutritional needs of young children were present and functioning in six of the 47houses (12.8%) where young children lived in this community. We found that 65% of the non-functional items might have been avoidable if the community had an effective repairs and maintenance service. Some householders’ daily living practices, including some cleaning and food preparation and cooking methods, as well as social factors such as conflict between family members or with neighbours, children left unsupervised, and crowding, contributed towards 16.8% of essential items being non-functional (Fletcher & Bridgeman 2000, Sutton 2005). In 19 (42.2%) of the 45 houses surveyed, faeces or other decaying matter was observed in the immediate living environment. At the time of the survey, the Indigenous Community Housing Organisation (ICHO) in the community did not have the capacity or the necessary resources to undertake the timely repair and maintenance of essential items. This problem is not unique to the study community; poor governance and ineffective systems impact negatively on service delivery in many remote communities (Ah Kit 2003, Indigenous Policy Unit 1999, Jardine-Orr et al. 2004).

Hygiene knowledge, attitudes and practices

We found the level of understanding and knowledge around the transmission mechanism of common childhood infections, and the role of hygiene behaviours, was poor. Community members appeared largely unaware of the health risks posed by young children’s faeces, nose and ear discharge, and exudates or purulent matter emanating from skin infections. If they were aware (alert to the risks), their behaviour and attitude indicated that they did not perceive the risks as serious. However, community members appeared to value good hygiene and expressed their desire to reduce the levels of infection among children. Our initial analysis revealed complex problems around childcare practices and parenting and further investigations enabled us to gain a better understanding of these problems.

Experience has taught Aboriginal people living in remote communities to distrust the motives and actions of those from outside their communities. The values that underpin political decision making, in particular when dealing with disadvantaged groups, are often sensitive and can have ethical implications. This applies particularly to lifestyle issues such as unsanitary living conditions and parenting practices. On one hand, individuals or communities can perceive raising these issues as confrontational. On the other hand, ignoring health inequities is not ethically acceptable. The tensions surrounding these issues cause authorities to allow unacceptable public health risks to continue without taking effective action, as in remote Aboriginal communities in the NT.

POOR CHILD GROWTH AND DEVELOPMENT

The high burden of infection and poor childhood growth

Growth faltering frequently occurs among Indigenous children living in remote NT communities with as many as 14 to 23% of children under 5 years reported to be underweight (d’Espaignet et al. 1998). Growth faltering affects not only children’s health and general wellbeing, but also their cognitive development and educational outcomes. It leads to a greater likelihood of developing chronic disease in adulthood and to social disadvantage throughout life (Graham & Power 2004, Hertzman & Power 2006, Kuh et al. 2004). Poor growth is frequently associated with low birth weight, social disadvantage, including low socioeconomic circumstances, low levels of education, poor housing conditions and unsanitary living environments, poor diet, nutrition–infection interactions, and enteric pathogens (Brewster 2003). Most, if not all, of these risk factors are currently present in remote Aboriginal communities.

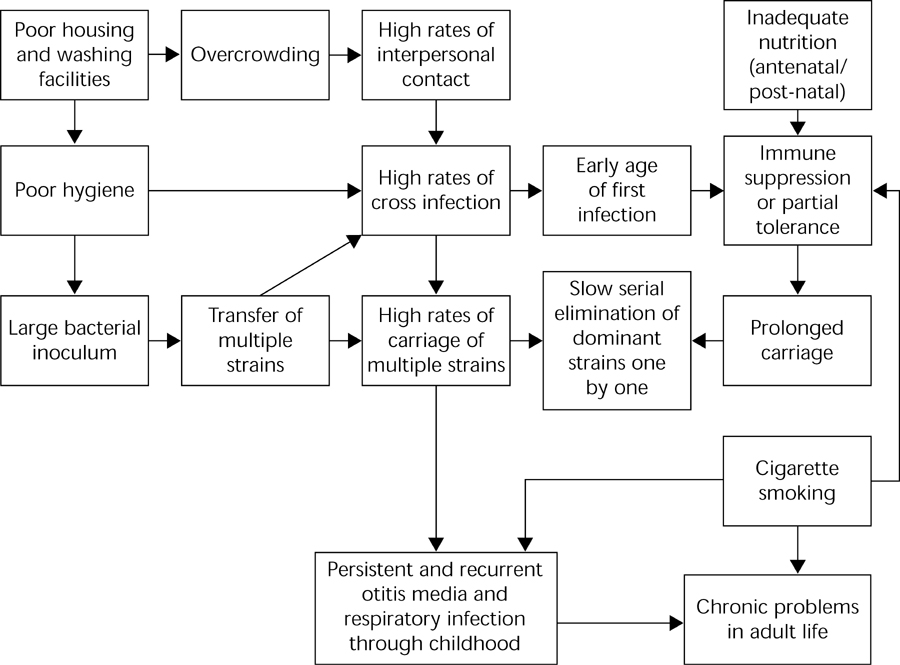

In the NT, an Indigenous infant aged between four weeks and 1 year is seven times more likely to be admitted to hospital than a non-Indigenous child of the same age. The majority of these admissions are for respiratory, infectious and parasitic diseases (69%), while the average number of conditions associated with each episode of hospitalisation is 2.7 (d’Espaignet et al. 1998). Unsatisfactory living conditions and poor personal hygiene are responsible for the high burden of preventable respiratory, enteric, ear, eye and skin infectious disease among children. Mathews (1997) developed a flowchart to illustrate the factors influencing endemicity and disease associated with respiratory bacteria among Indigenous Australian children living in remote communities (see Figure 22.1).

Figure 22.1 The factors influencing endemicity and disease associated with respiratory bacteria among children Source: Mathews 1997, p 292

This causal network relates specifically to the transmission of respiratory bacteria. However, the transmission networks for skin and diarrhoeal diseases are similar.

Comparing current child care and parenting practices with those observed in the 1970s indicates that practices have changed very little (Hamilton 1981, Middleton & Francis 1976). The practices that continue today include shared mothering, encouraging young children to be independent and to explore and come to terms with their environment, the expectation that mothers will not cause their children distress, and approaches to child care that largely focus on protecting children from the physical dangers in the environment. In many cases, these practices present barriers to meeting the health and hygiene needs of young children. These childcare factors need to be considered in the current social context of many remote Indigenous communities where high levels of family and community dysfunction exist, and where child health and welfare issues are broader than children not having their hygiene needs met (Pearson 2000). Child neglect is recognised as a serious problem in many remote Indigenous communities (Libesman 2004, Stanley et al. 2003, Sutton 2001).

Family and community dysfunction

Forced relocation, loss of identity, plus rapid social and subsequent cultural change have contributed to individual, family and community dysfunction among Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people (Aboriginal Medical Services Alliance of the NT 2000, Devitt et al. 2001, Hunter 1995). These pressures have contributed to alcohol abuse, violence and poor physical and mental ill health. Hunter (1995) notes Indigenous people are so socially disadvantaged that they are more likely to encounter multiple risk factors with access to fewer sources of resilience. Not writing specifically in the case of Australian Indigenous people, Kleinman notes that:

… severe economic, political and health constraints create endemic feelings of hopelessness and helplessness, where demoralisation and despair are responses to real conditions of chronic deprivation and persistent loss, where powerlessness is not a cognitive distortion but an accurate mapping of one’s place in an oppressive social system …

The land rights movement over the past two decades has allowed many Indigenous people in the NT to return to their homelands. However, Dodson (1994) noted that while the return of people to their country will help to promote improved health, the mere ownership of land, in the Western legalistic sense, would not immediately resolve the historical and contemporary social and cultural pressures they experience.

LOOKING TOWARDS THE FUTURE

Essential conditions

Two premises underlie the following discussion. They are integral to the success of Indigenous policies and programs. These include that there is strong political will to support a long-term policy strategy to improve living conditions and hygiene in remote Aboriginal communities. In addition, that it is possible to win the trust and cooperation of communities through using participatory action approaches to finding solutions and resolving problems. Without both these conditions in place, the chances of improving living conditions and environmental health in remote communities in the near future are low.

An ecological approach

Our case study research findings show that to achieve good environmental health in disadvantaged communities to the extent that it will improve child health, interventions are needed in a number of areas and on a number of levels. Appropriate interventions include housing, health promotion, childcare and community governance. Therefore, it is necessary to harmonise sectoral priorities and approaches through targeted collaboration and partnerships to maximise health benefits outside the health sector (Listorti & Doumani 2002). Effective systems need to be developed at community level but also at different levels of government in different departments. The constructs of social ecological theory (Stokols 1996), which include analysing problems in the contexts in which they occur, provides a suitable basis on which to build comprehensive public health policy. Social ecological theory appears to offer the greatest capacity to address complex community problems. An ecological approach will require the development of multiple and multifaceted interventions, as well as coordination of activities across several sectors. Using this approach is more likely to lead to structural and system changes and the use of proactive approaches (Department of Health and Aging 2004, Listorti & Doumani 2002).

International experience indicates that coordinating interventions between health and other sectors will do more to improve health in contexts of poverty than a series of single-sector interventions. Environmental health problems tend to be multisectoral and therefore require multisectoral solutions. While single-sector interventions might have the potential to contribute to health improvements, it appears that interventions across a number of sectors are necessary in order to achieve substantial improvement in health outcomes for children. Single-sector interventions might not only be relatively ineffective, but might also be a waste of resources if they are not complemented by other required interventions. For example, constructing houses but not adequately addressing lifestyle and other behavioural issues. Putting health in its broader environmental setting can help fulfil one of the most important rules of public health: to do no harm. Single-sector projects might inadvertently do harm by introducing policies and promoting interventions that fail to address associated health risks (Listorti & Doumani 2002). The manner in which housing was (and still is) introduced into remote Aboriginal communities provides an example of this.

Sectoral harmonisation

That communities benefit by sectoral harmonisation is well recognised (Listorti & Doumani 2002). Sectoral harmonisation is essential if integrated service delivery is to be achieved at the community level. The scope of responsibilities that fall in the public health domain makes it feasible that public health takes on the role of coordinating interventions across sectors and takes a key role in formulating policy. This would ensure that improved health outcomes are the primary focus of all activities across sectors. National frameworks such as The National Aboriginal Health Strategy (NAHS) (NATSIHC 2003), The National Environmental Health Strategy (Department of Health and Aged Care 1999), and the National Public Health Strategic Framework for children 2005–2008 (National Public Health Partnership 2005), offer sound policy and program directions. The federal government is currently reviewing policies and programs concerned with funding and administering Indigenous housing (Department of Families, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs 2006). This offers opportunities to align housing policies more closely with those of other sectors. In addition, the federal government has introduced a new system to administer Indigenous affairs. New initiatives that offer opportunities for a different approach include:

- changing the way governments work together, and the way governments work with Indigenous people

- announcing that early childhood intervention, achieving safer communities, and building Indigenous wealth, employment and entrepreneurial culture, are priority national action areas

- shifting the policy approach away from ‘community control’ to ‘shared responsibility’, with more flexible and coordinated funding arrangements to be able to take account of local needs, and

- adopting a strategic whole-of-government approach across all agencies, while working more closely with state, territory and local governments (Department of Families, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs 2007).

- announcing that early childhood intervention, achieving safer communities, and building Indigenous wealth, employment and entrepreneurial culture, are priority national action areas

Time will tell if the political will is there to see these changes through and if the rhetoric is realised at the community level. The evaluation of the NAHS framework found that, while the content of this document remains highly relevant, little of its direction has been implemented at the community level (National Aboriginal Health Strategy Working Party 1994). The challenge to implement a whole-of-government approach and achieve integrated service delivery at the community level should not be underestimated. A recent review of the Council of Australian Governments (COAG) trials highlights the difficulties that governments and community leaders have in understanding how to work differently, as well as to take action to address local priorities in communities (Morgan Disney and Associates 2006).

Enabling environments

There is a greater likelihood that community members will adapt their practices if the suggested changes fit easily within their current social, economic, cultural and political environments. Before interventions are introduced that affect individuals, families or groups, systems and processes must be in place in communities that enable support rather than provide additional barriers to voluntary behaviour change (Pearson 2005). Here are two examples that illustrate a poor fit between the intervention and the environment:

1. Health staff providing education and promoting behaviours that are dependent on infrastructure or services not available in the community or which require people to purchase items that are available but not affordable, or items that are not available in the community.

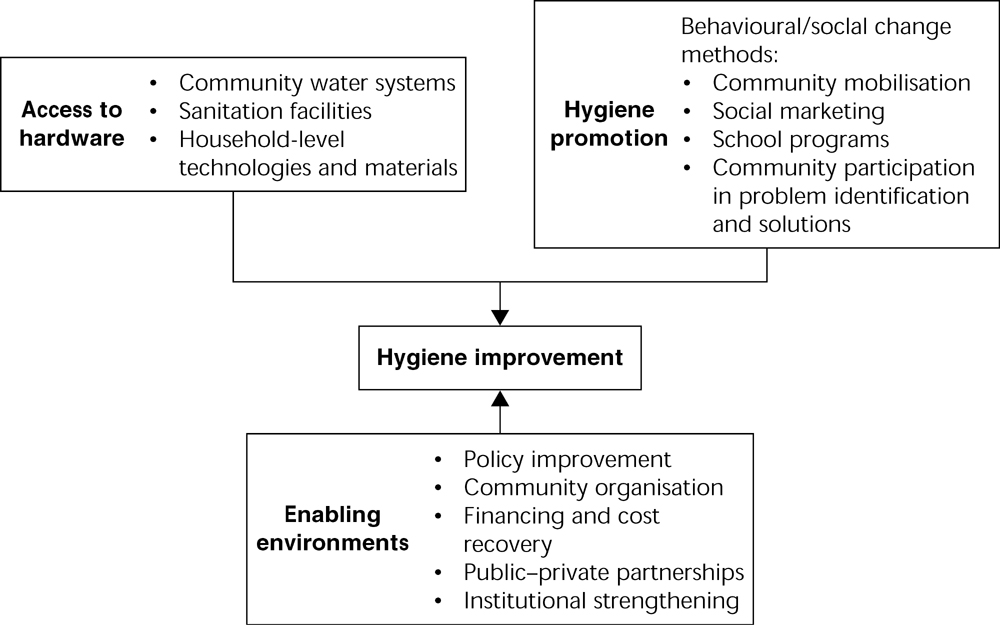

A framework that can assist in understanding the concepts discussed here is the Hygiene Improvement Framework (HIF) (see Figure 22.2). This framework can be used to plan and develop interventions to meet local priorities, as well as serve as a monitoring and evaluation tool (Appleton & van Wijk 2003, Kolesar et al. 2003, MacDougall & McGahey 2003).

Figure 22.2 The Hygiene Improvement Framework Source: Bateman and McGahey 2001

The HIF was developed for the Environmental Health Project as an integrated approach to prevent diarrhoeal disease in developing countries (Bateman & McGahey 2001). The framework has three core components; that is, access to hardware, hygiene promotion and promoting enabling environments. The first two components, access to hardware and hygiene promotion, block the pathways to contamination and the spread of infection. Many of the physical and social barriers to achieving improved hygiene for children, as described in the case study, are problems that would come under these two components. The third component, an enabling environment, concerns policy leadership, governance, and systems support that allow for effective and sustained service delivery. In this component, as in the others, overarching policies play a crucial role in enunciating the principles and the approaches to be followed when planning, developing and implementing interventions.

The HIF provides only the components that represent the essential structure of a hygiene-improvement program. The broad theory or rationale that support the construct of the framework is that all three components of access to hardware, hygiene promotion and enabling environments are required to be in place before hygiene and health improve.