CASE 22

Dawn, a 15-year-old African American girl, was debating whether she should go on the spring ski trip that she had planned for so long. She had noticed stiffness in both her hips (and hands) each morning and wondered if that would affect her skiing. However, since the stiffness abated during the day, she thought that she would go, even if it meant only skiing in the afternoons. She enjoyed the trip, particularly since the weather was so warm and sunny, but she was concerned when she noticed a rash on her face. The rash persisted after she returned and so she went to see her family physician, who recognized the rash as being a classic presentation of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), and so he referred her to a local rheumatologist.

On questioning, the rheumatologist learned that there was no history of arthritic-type diseases in the family, although a distant cousin had recently been diagnosed with an inflammatory bowel disorder. A urine sample was found to be normal, indicating that glomerulonephritis was not a problem. A complete blood cell count was performed, along with an assay for antinuclear antibodies (ANA). The white blood cell count indicated a mild lymphopenia and neutropenia, reduced red blood cell count, and a severe drop in platelet count (see Appendix for reference values). The ANA antibody titer was significantly high (normal range: 1:40 to 1:120 depending on the laboratory). How would you proceed?

QUESTIONS FOR GROUP DISCUSSION

RECOMMENDED APPROACH

Implications/Analysis of Clinical History

A red butterfly rash on cheeks after sun exposure in a teenage female is a classic presentation of SLE and has been shown to lead to early testing and diagnosis. The rash results from blood leaking out of damaged blood vessels (immune complex–mediated inflammation) into the skin. However, recent studies have shown that when the initial presentation is arthritis (joint inflammation) and/or arthralgia (joint pain), diagnosis is often delayed, despite the fact that these are the most common initial symptoms (60% of patients studied).

Implications/Analysis of Laboratory Tests

Blood Cell Counts

Dawn’s white blood cell count indicated a mild lymphopenia and neutropenia, which is very common in SLE patients and most likely results from autoantibodies to white cells. Low platelet count (thrombocytopenia), also common in SLE patients, can result in bleeding that manifests as bruises and/or rash. Dawn’s red blood cell count was low, indicating anemia, and thus direct and indirect Coombs’ tests were ordered to determine whether the anemia was due to the presence of autoantibodies that target proteins on the red blood cells. (See Additional Laboratory Tests.)

Additional Laboratory Tests

Anti–Red Blood Cell Antibodies

In patients with anemia, the direct and indirect Coombs’ tests are used to establish whether there is evidence of autoimmune hemolytic anemia, which can occur in SLE when autoantibodies against erythrocytes are present. In Dawn’s case, both the direct and indirect Coombs’ tests were negative (see Case 15), indicating that this was not the cause of the anemia.

Complement C3 and C4

Dawn’s serum C3 level was significantly reduced (normal: see Appendix). In general, the serum level of C3 and C4 complement proteins in SLE patients is decreased because immune complexes bind to and activate the classical pathway of complement. Complement activation triggers an enzymatic cascade in which C3 and C4 are cleaved and biologically active fragments are produced. Often the depletion in these proteins is proportional to the severity of the disease (i.e., number of immune complexes). In such cases the level of C3 and C4 is said to be “concordant” with disease activity, and thus can be used to monitor disease and its response to therapy. Successful immunosuppressive therapy is reflected in a rise in the serum level of C3 and C4. Nephelometry of either C3 or C4 (see Case 11) is sufficient to monitor disease in such patients.

THERAPY

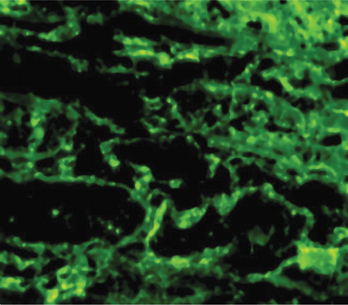

Dawn will have to be monitored carefully because immune complex deposition in the glomerulus is the trigger for inflammation and glomerulonephritis (Fig. 22-1). Proteins or red blood cells in the urine would signal this type of inflammation and so Dawn’s immunosuppressive therapy would need to be increased and accompanied by periodic administration of cyclophosphamide intravenously.

ETIOLOGY: SYSTEMIC LUPUS ERYTHEMATOSUS

Breakdown in Tolerance

Potentially autoreactive B cells probably exist normally in the circulation of all individuals, but it must be noted that we normally do not activate these B cell clones. Autoimmunity in general, and SLE in particular, represent a breakdown in normal “self tolerance” mechanisms. Exactly why this occurs remains unclear. For SLE, it seems that tolerance breakdown may result from a failure in normal immunoregulatory populations of T cells.