CASE 21 Tamponade Following a Coronary Intervention

Cardiac catheterization

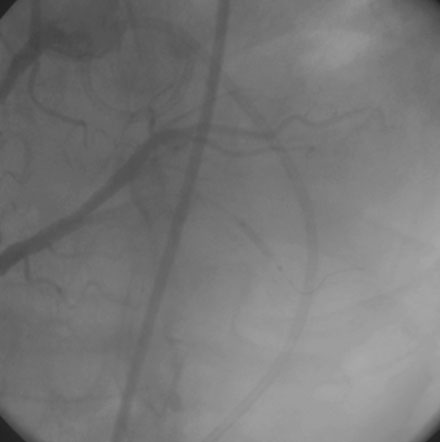

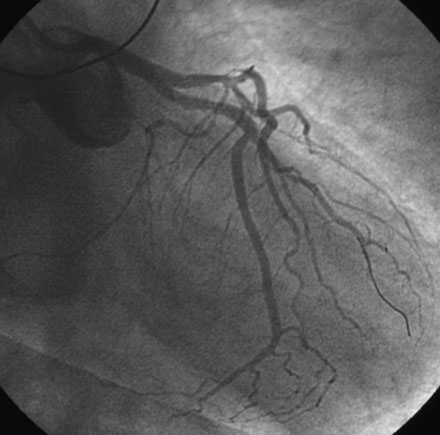

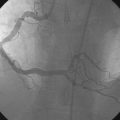

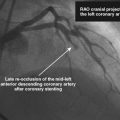

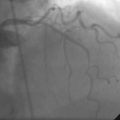

The operator performed right coronary angiography to determine the source of the bleeding. This showed wide patency of the stent in the right coronary artery with no evidence of a perforation at the site of the stent (Figure 21-1); however, contrast was observed in the pericardial space (Video 21-1) and the pigtail catheter continued to drain blood. Additional views were performed; free-flowing contrast was apparent from the distal tip of the posterior descending artery in an anteroposterior view with cranial angulation (Video 21-2). A 2.5 mm balloon was inflated in the posterior descending artery proximal to the perforation and effectively stopped the bleeding (Figure 21-2). While the balloon remained inflated, the patient remained hemodynamically stable with no additional blood accumulation from the pericardial drain. A cardiothoracic surgeon was informed of the patient’s condition and alerted to the possible need for emergency surgery to correct the problem. Meanwhile, 12 units of platelets were rapidly infused and an infusion of packed red blood cells begun. After 10 minutes, the balloon in the posterior descending artery was deflated. Repeat angiography showed ongoing contrast extravasation from the distal posterior descending artery. The balloon was then reinflated for 20 minutes. Angiography after balloon deflation confirmed no further evidence of contrast extravasation (Video 21-3). The patient was observed in the cardiac catheterization laboratory and another angiogram performed 10 minutes later showed no further contrast extravasation. No additional blood was aspirated from the pericardial catheter. In total, 2.6 L of blood drained from the pericardial catheter and he received a total of 4 units of packed red blood cells in the cath lab.

Discussion

Tamponade is a very rare complication of coronary intervention, with an incidence in one recent study of 0.12%.1 Coronary perforation caused by the guidewire, balloon, stent, or other interventional device is responsible for nearly all cases of tamponade. Rarely, tamponade may occur from perforation from a temporary pacemaker lead used to support the intervention or from free-wall rupture complicating an acute myocardial infarction.

Overall, tamponade occurs in 12% to 25% of coronary perforations, but is dependent upon the type of perforation present.2,3 Ellis and colleagues3 classified perforations by angiographic criteria as follows: Type I are limited to a crater extending outside of the lumen; Type II are characterized by the presence of a contrast blush in the pericardium or myocardium without an exit hole greater than 1 mm in diameter; and Type III perforations are present when there is free-flowing contrast through an exit hole greater than 1 mm. A variation of Type III is known as “Type III cavity-spilling,” defined as perforation into an anatomic chamber such as a ventricle or the coronary sinus. Tamponade complicates about 10% of Type I and II perforations, but occurs in about 60% of Type III perforations.3 The patient shown in this case had a Type II perforation, with contrast seen in the pericardium but with a very small exit hole caused by the guidewire. Guidewire perforations are more commonly seen when hydrophilic or stiff-tipped wires are used to cross complex lesions or chronic total occlusions. In this case, the tip of a conventional, floppy-tipped guidewire perforated a very distal vessel. This case emphasizes the importance of carefully monitoring the location of the wire tip during the course of an intervention to be sure the tip does not stray into a small branch where it may perforate if advanced inadvertently.

When a perforation is immediately recognized at the time of the intervention, steps may be promptly taken to prevent the development of tamponade. In this case, the wire perforation was not appreciated and hypotension from tamponade developed after he left the catheterization laboratory, resulting in a medical emergency. This is not unusual. Tamponade may result from a slow, steady, unrecognized bleeding caused by an occult wire perforation or from a deep dissection at the site of the intervention. This process may be fueled by powerful platelet antagonists such as the platelet glycoprotein IIb/IIIa receptor antagonists. Only about half of cases of tamponade develop in the cath lab. In the remaining cases, tamponade may not be manifest until many hours after the intervention.1 Thus, tamponade from an occult perforation should be strongly suspected in a patient with progressive hypotension after a coronary intervention.

1. Fejka M., Dixon S.R., Safian R.D., O’Neill W.W., Grines C.L., Finta B., Marcovitz P.A., Kahn J.K. Diagnosis, management, and clinical outcome of cardiac tamponade complicating percutaneous coronary intervention. Am J Cardiol. 2002;90:1183-1186.

2. Fasseas P., Orford J.L., Panetta C.J., Bell M.R., Kenktas A.E., Lennon R.J., Holmes D.R., Berger P.B. Incidence, correlates, management, and clinical outcome of coronary perforation: Analysis of 16,298 procedures. Am Heart J. 2004;147:140-145.

3. Ellis S.G., Ajluni S., Arnold A.Z., Popma J.J., Bittl J.A., Eigler N.L., Cowley M.J., Raymond R.E., Safian R.D., Whitlow P.L. Increased coronary perforation in the new device era: Incidence, classification, management and outcome. Circulation. 1994;90:2725-2730.