CHAPTER 21 Mechanical Ventilation in Critical Illness

1 Why might a patient require mechanical ventilation?

There are three conditions for which mechanical ventilation (MV) may be required:

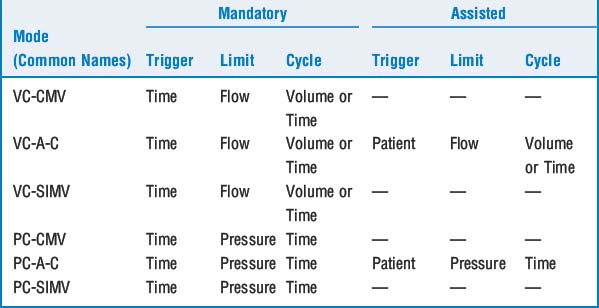

3 What are the most commonly used modes of positive-pressure ventilation?

11 What are trigger variables?

All modern ICU ventilators constantly measure one or more of the phase variables (i.e., pressure, volume, flow, or time) (Table 21-1). Inspiration occurs when one of these variables reaches a preset value. Clinically this is referred to as triggering the ventilator. The following conditions are necessary to initiate a breath under each individual variable:

Pressure triggering: requires patient-initiated effort to decrease circuit pressure below a preset value (e.g., −2 cm H2O below baseline end-expiratory pressure is common).

Pressure triggering: requires patient-initiated effort to decrease circuit pressure below a preset value (e.g., −2 cm H2O below baseline end-expiratory pressure is common). Flow or volume triggering: again requires patient effort that results in a drop in the flow rate or volume of gas that is continually present within the circuit.

Flow or volume triggering: again requires patient effort that results in a drop in the flow rate or volume of gas that is continually present within the circuit. Time triggering: does not require patient effort but occurs when the set respiratory rate on the ventilator becomes due.

Time triggering: does not require patient effort but occurs when the set respiratory rate on the ventilator becomes due.Two potentially hazardous forms of triggering have also been identified:

Auto-triggering: occurs when the ventilator is rapidly cycling without apparent patient effort. If the triggering system is overly sensitive (e.g., the pressure is set for −1 cm H2O) and excessive condensation is present within the circuit, water motion can result in a drop in circuit pressure, causing auto-cycling.

Auto-triggering: occurs when the ventilator is rapidly cycling without apparent patient effort. If the triggering system is overly sensitive (e.g., the pressure is set for −1 cm H2O) and excessive condensation is present within the circuit, water motion can result in a drop in circuit pressure, causing auto-cycling.14 What is the role of positive end-expiratory pressure?

16 What is intrinsic or auto-positive end-expiratory pressure?

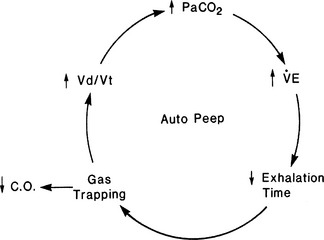

Failure to recognize the presence of auto-PEEP can lead to inappropriate ventilator changes (Figure 21-1). The only way to detect and measure PEEPi is to occlude the expiratory port at end expiration while monitoring airway pressure. Decreasing rate or increasing inspiratory flow (to increase I:E ratio) may allow time for full exhalation. Administering a bronchodilator therapy in the setting of bronchospasm is usually beneficial.

17 What are the side effects of PEEPe and PEEPi?

Cardiac output may be decreased because of increased intrathoracic pressure, producing an increase in transmural right atrial pressure and a decrease in venous return. PEEP also increases pulmonary artery pressure, potentially decreasing right ventricular output. Dilation of the right ventricle may cause bowing of the interventricular septum into the left ventricle, thus impairing filling of the left ventricle, decreasing cardiac output, especially if the patient is hypovolemic.

Cardiac output may be decreased because of increased intrathoracic pressure, producing an increase in transmural right atrial pressure and a decrease in venous return. PEEP also increases pulmonary artery pressure, potentially decreasing right ventricular output. Dilation of the right ventricle may cause bowing of the interventricular septum into the left ventricle, thus impairing filling of the left ventricle, decreasing cardiac output, especially if the patient is hypovolemic. Incorrect interpretation of cardiac filling pressures. Pressure transmitted from the alveolus to the pulmonary vasculature may falsely elevate the readings.

Incorrect interpretation of cardiac filling pressures. Pressure transmitted from the alveolus to the pulmonary vasculature may falsely elevate the readings. Overdistention of alveoli from excessive PEEP decreases blood flow to these areas, increasing dead space (Vd/Vt).

Overdistention of alveoli from excessive PEEP decreases blood flow to these areas, increasing dead space (Vd/Vt).24 Is ventilation in the prone position an option for patients who are difficult to oxygenate?

26 How is the patient who is fighting the ventilator approached?

KEY POINTS: Mechanical Ventilation in Critical Illness

1. Alsaghir A.H., Martin C.M. Effects of prone positioning in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome: a meta-analysis. Crit Care Med. 2008;36:603-609.

2. Fessler H.E., Hess D.R. Does high-frequency ventilation offer benefits over conventional ventilation in adult patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome? Respir Care. 2007;52:595-608.

3. Kallet R.H., Branson R.D. Do the NIH ARDS Clinical Trials Network PEEP/FIO2 tables provide the best evidence-based guide to balancing PEEP and FIO2 settings in adults? Respir Care. 2007;52:461-477.

4. MacIntyre N.R. Is there a best way to set tidal volume for mechanical ventilatory support? Clin Chest Med. 2008;29:225-231.

5. Nichols D., Haranath S. Pressure control ventilation. Crit Care Clin. 2007;23:183-199.

6. Steinburg K.P., Kacmarek R.M. Should tidal volume be 6 mL/kg predicted body weight in virtually all patients with acute respiratory failure? Respir Care. 2007;52:556-567.