CHAPTER 21

Elbow Arthritis

Charles Cassidy, MD; Chien Chow, MD

Definition

In the simplest of terms, arthritis of the elbow reflects a loss of articular cartilage in the ulnotrochlear and radiocapitellar articulations. Destruction of the articulating surfaces and bone loss or, alternatively, excess bone formation in the form of osteophytes can be present. Joint contractures are common. Joint instability can result from inflammatory or traumatic injury to the bone architecture, capsule, and ligaments. The spectrum of disease ranges from intermittent pain or loss of motion with minimal changes detectable on radiographs to the more advanced stages of arthritis with a limited, painful arc of motion and radiographic demonstration of osteophyte formation, cysts, and loss of joint space. Ultimately, these destructive processes may result in complete ankylosis or total instability of the elbow.

The major causes of elbow arthritis are the inflammatory arthropathies, of which rheumatoid arthritis is the predominant disease. Arthritis of the elbow eventually develops in approximately 20% to 50% of patients with rheumatoid arthritis [1]. Involvement of the elbow in juvenile rheumatoid arthritis is not uncommon. Other inflammatory conditions affecting the elbow joint are systemic lupus erythematosus, the seronegative spondyloarthropathies (ankylosing spondylitis, psoriatic arthritis, Reiter syndrome, and enteropathic arthritis), and crystalline arthritis (gout and pseudogout). Post-traumatic arthritis may result from intra-articular fractures of the elbow. Osteonecrosis of the capitellum or trochlea, leading to arthritis, has also been described [2,3]. Primary osteoarthritis of the elbow is a rare condition, responsible for less than 5% of elbow arthritis [4]. Interestingly, the incidence is significantly higher in the Alaskan Eskimo and Japanese populations [5]. Primary elbow arthritis usually affects the dominant arm of men in their 50s. Repetitive, strenuous arm use appears to be a risk factor; primary elbow arthritis has been reported in heavy laborers, weightlifters, and throwing athletes. Synovial chondromatosis is another rare cause of elbow arthritis [3].

Symptoms

The symptoms of elbow arthritis reflect, in part, the underlying etiology and severity of the disease process. Regardless of the etiology, however, the inability to fully straighten (extend) the elbow is a nearly universal complaint of patients with elbow arthritis. Associated symptoms of cubital tunnel syndrome (ulnar neuropathy at the elbow) include numbness in the ring and small fingers, loss of hand dexterity, and aching pain along the ulnar aspect of the forearm. Cubital tunnel syndrome is neither uncommon nor unexpected, given the proximity of the ulnar nerve to the elbow joint (see Chapter 27).

Patients with early rheumatoid involvement complain of a swollen, painful joint with morning stiffness. Progressive loss of motion or instability is seen in later stages. Compression of the posterior interosseous nerve by rheumatoid synovitis can occasionally produce the inability to extend the fingers.

Patients with crystalline arthritis of the elbow may complain of severe pain, swelling, and limited motion; an expedient evaluation is warranted to rule out a septic elbow in such cases.

Post-traumatic or idiopathic arthritis of the elbow, in contrast, usually is manifested with painful loss of motion without the significant effusions, warmth, or constant pain associated with an inflamed synovium. These patients usually complain of pain at the extremes of motion secondary to osteophyte impingement, and they typically have more trouble extending the elbow than flexing it. Pain throughout the arc of motion implies advanced arthritis. The final stages of arthritis, irrespective of cause, can include complaints of severe pain and decreased motion that hinder activities of daily living as well as the cosmetic deformity of the flexed elbow posture.

Physical Examination

Physical examination findings vary according to the cause and stage of the elbow arthritis. A flexion contracture is almost always present. The range of motion should be monitored at the initial examination and at subsequent follow-up examinations.

Normal adult elbow range of motion in extension-flexion is from 0 degrees to about 150 degrees; pronation averages 75 degrees, and supination averages 85 degrees. A functional range of motion is considered to be 30 to 130 degrees, with 50 degrees of both pronation and supination [6].

All other joints should be assessed as well. Strength should be normal but may be impaired in long-standing elbow arthritis because of disuse or, in more acute cases, pain. Weakness may also be noted in the presence of associated neuropathies. In the absence of associated neuropathies, deep tendon reflexes and sensation should be normal.

Associated ulnar nerve irritation can produce a sensitive nerve with the presence of Tinel sign over the cubital tunnel, diminished sensation in the small finger and ulnar half of the ring finger, and weakness of the intrinsic muscles (see Chapter 27). Numbness provoked by acute flexion of the elbow for 30 to 60 seconds is a positive elbow flexion test result.

Effusions, synovial thickenings, and erythema are commonly noted in the inflammatory arthropathies during acute flares. Loss of motion in flexion and extension as well as in pronation and supination can be present because the synovitis affects all articulating surfaces in the elbow. Pain, limited motion, and crepitus worsen as the disease progresses. On occasion, rheumatoid destruction of the elbow will produce instability, which may be perceived by the patient as weakness or mechanical symptoms. Examination of such elbows will demonstrate laxity to varus and valgus stress; posterior instability may also be seen.

In contrast, progressive primary or post-traumatic arthritis of the elbow results in stiffness. The loss of extension is usually worse than the loss of flexion. Pain is present with forced extension or flexion. Crepitus may be palpable throughout the arc of flexion-extension or with forearm rotation.

Functional Limitations

The elbow functions to position the hand in space. Significant loss of extension can hinder an individual’s ability to interact with the environment, making activities that require nearly full extension, like carrying groceries or briefcases, painful. Significant loss of flexion can interfere with activities of daily living such as eating, shaving, and washing. A normal shoulder can compensate well for a lack of pronation, whereas a normal shoulder, wrist, and cervical spine can compensate, albeit awkwardly, for a lack of full elbow flexion. There is no simple solution for a significant lack of elbow extension; the body must be moved closer to the desired object. Compensatory mechanisms are often impaired in patients with rheumatoid arthritis, magnifying the impact of the elbow arthritis on function.

Diagnostic Studies

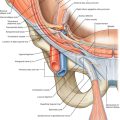

Anteroposterior, lateral, and oblique radiographic views of the elbow are usually sufficient for diagnosis of elbow arthritis. The radiographs should be inspected for joint space narrowing, osteophyte and cyst formation, and bone destruction. For the rheumatoid patient, the Mayo Clinic radiographic classification of rheumatoid involvement is useful (Table 21.1) [7]. Dramatic loss of bone is evident as the disease progresses (Fig. 21.1). This pattern of destruction is not seen, however, in the post-traumatic or idiopathic patient. Radiographic features in these patients include spurs or osteophytes on the coronoid and olecranon, loose bodies, and narrowing of the coronoid and olecranon fossae (Fig. 21.2).

Table 21.1

Radiographic Classification of Rheumatoid Arthritis [7]

| I | Synovitis with a normal-appearing joint |

| II | Loss of joint space but maintenance of the subchondral architecture |

| IIIa | Alteration of the subchondral architecture |

| IIIb | Alteration of the architecture with deformity |

| IV | Gross deformity |

Magnetic resonance arthrography or computed tomographic arthrography may help localize suspected loose bodies. Magnetic resonance imaging is most valuable for confirmation of suspected osteonecrosis.

The diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis will have already been made in the majority of patients who present with rheumatoid elbow involvement. When isolated inflammatory arthritis of the elbow is suspected, appropriate serologic studies may include analysis of rheumatoid factor, antinuclear antibody, HLA-B27, and erythrocyte sedimentation rate. Elbow aspiration may be needed to rule out a crystalline or infectious cause in patients who present with a warm, stiff, swollen, and painful joint with no history of trauma or inflammatory arthritis.

Treatment

Initial

Treatment of elbow arthritis depends on the diagnosis, degree of involvement, functional limitations, and pain. When the elbow is one of a number of joints actively involved with inflammatory arthritis, the obvious treatment is systemic. Disease-modifying agents have had a dramatic effect in relieving symptoms and retarding the progression of arthritis for many of these patients. For systemic disease, a rheumatology consultation can be beneficial.

The initial local treatment of an acutely inflamed elbow joint includes rest. A simple sling places the elbow in a relatively comfortable position. The patient should be encouraged to remove the sling for gentle range of motion exercises of the elbow and shoulder several times daily. Icing of the elbow for 15 minutes several times a day for the first few days may be beneficial.

Nonoperative treatment of primary osteoarthritis of the elbow primarily consists of rest, activity modification, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Oral analgesics may help with pain control. Topical treatments such as capsaicin can be tried as well.

Patients who have associated cubital tunnel symptoms are instructed to avoid direct pressure over the elbow and to avoid prolonged elbow flexion. A static night splint that maintains the elbow in about 30 degrees of flexion may help alleviate cubital tunnel symptoms (see Chapter 27).

Rehabilitation

Once the acute inflammation has subsided, physical or occupational therapy may be instituted to regain elbow motion and strength and to educate the patient in activity modification and pain control measures.

Therapy should focus on improving range of motion and strength throughout the upper body with a goal of improving function regardless of the degree of elbow arthritis. Adaptive equipment, such as reachers, can be recommended. Ergonomic workstation equipment may also be useful (e.g., voice-activated computer software, forearm rests).

Modalities such as ultrasound and iontophoresis may help with pain control.

Nighttime static, static-progressive, or dynamic extension splinting may be indicated to relieve significant elbow contractures. Braces may be effective in the setting of instability. The goal of therapy is functional rather than full elbow motion.

In primary osteoarthritis of the elbow, corrective splinting is not indicated because bone impingement is usually present. Similarly, therapy may actually aggravate the symptoms and should be ordered judiciously.

Rehabilitation is critical to the success of surgical procedures around the elbow. The rheumatoid patient commonly has multiple joint problems that must not be neglected during treatment of the elbow. The shoulder is at particular risk for stiffness. A good operation, a motivated patient, and a knowledgeable and skillful therapist are necessary to optimize postoperative results. Postoperative rehabilitation depends on the procedure and the surgeon’s preference. However, in general, physical or occupational therapy should be recommended to restore range of motion and strength.

Procedures

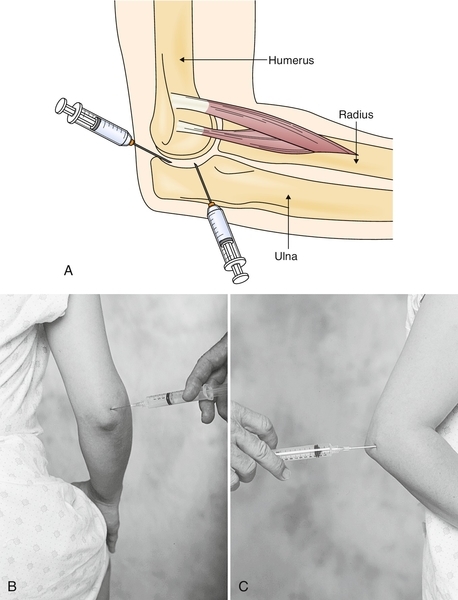

For recalcitrant symptoms, intra-articular steroid injections are effective in relieving the pain associated with synovitis (Fig. 21.3).

The elbow joint is best accessed through the “soft spot,” the center of the triangle formed by the lateral epicondyle, the tip of the olecranon, and the radial head. The patient is placed with the elbow between 50 and 90 degrees of flexion. For the posterolateral approach, the lateral epicondyle and the posterior olecranon are palpated. Under sterile conditions, with use of a 25-gauge, 11⁄2-inch needle, 3 to 4 mL of an anesthetic-corticosteroid mixture (e.g., 1 mL of 80 mg/mL methylprednisolone and 3 mL of 1% lidocaine) is injected. The needle is directed proximally toward the head of the radius and medially into the elbow joint. No resistance should be noted as the needle enters the joint. If an effusion is present, aspiration may be done before the anesthetic-corticosteroid mixture is injected.

For the posterior approach, the olecranon fossa is palpated just proximal to the tip of the olecranon. The needle is then inserted above the superior aspect of and lateral to the olecranon. Again, it should enter the joint without resistance.

Postinjection care may include icing of the elbow for 10 to 20 minutes after the injection and then two or three times daily thereafter. The patient should be informed that the pain may worsen for the first 24 to 36 hours and that the medication may take 1 week to work.

In general, repeated injections are not recommended. Although the intra-articular steroids are effective in treating synovitis, they also temporarily inhibit chondrocyte synthesis, an effect that could potentially accelerate arthritis.

Surgery

Patients who have failed to respond to treatment after 3 to 6 months of adequate medical therapy are potential candidates for surgery. Refractory pain is the best indication for surgery. In assessment of the surgical candidate with primary elbow arthritis, it is important to listen carefully to the patient’s complaints. Many patients are dissatisfied with the simple fact that they cannot fully straighten the elbow. Such patients will not be fully satisfied with surgery.

Intermittent locking or catching, suggestive of a loose body, is often best treated with arthroscopy. Pain at the extremes of motion is consistent with olecranon and coronoid osteophyte impingement. An ulnohumeral arthroplasty, or surgical débridement of the elbow joint, may be recommended. Traditionally, open surgical techniques have been performed to remove impinging osteophytes. More recent arthroscopic advances have permitted this débridement to be performed in a less invasive manner, with potentially less morbidity. However, arthroscopic treatment of elbow contractures is a technically demanding procedure [8]. Ulnohumeral arthroplasty is successful at achieving its principal goal—pain relief at the extremes of motion. However, it is only marginally successful at actually improving motion, with an average improvement in extension of 7 to 12 degrees and an average improvement in flexion of 8 to 17 degrees in four reported series [4,9–11]. Overall, 85% of patients in these series were satisfied with the results. As expected, the results deteriorate with time as the arthritis progresses.

Less commonly, patients with primary arthritis complain of pain throughout the arc of motion. Their radiographs will probably demonstrate advanced arthritis with severe joint space narrowing. Simple removal of the osteophytes is not likely to be successful. Total elbow arthroplasty would seem to be a reasonable option. However, unlike their rheumatoid counterparts, most of these patients are otherwise healthy, vigorous people who would regularly stress their joint replacement. For this reason, total elbow arthroplasty in this setting is best reserved for the sedentary patient older than 65 years [12].

For the younger patient with advanced primary arthritis, a distraction interposition arthroplasty is recommended [13–15]. This procedure involves a radical débridement of the joint followed by a resurfacing of the joint surfaces with an interposition material, such as autologous fascia lata or allograft Achilles tendon. A hinged external fixator is then applied, which will protect the healing interposition material while simultaneously maintaining elbow stability and permitting motion. In the one relatively large series of distraction interposition arthroplasty [15], pain relief was satisfactory in 69% of patients at an average of 5 years postoperatively. An advantage of interposition arthroplasty is the potential for conversion to total elbow arthroplasty, ideally after the age of 60 years [16], but this procedure certainly does not produce a normal elbow.

Other nonimplant surgical options include elbow arthrodesis and resection arthroplasty. There is no ideal position for an elbow fusion. The elbow looks more cosmetically appealing when it is relatively straight. However, this position is relatively useless. Consequently, elbow arthrodesis is performed rarely, usually in the setting of intractable infection. Resection arthroplasty is an option for a failed total elbow arthroplasty. This procedure permits some elbow motion, although the elbow tends to be very unstable.

For the rheumatoid patient with elbow arthritis, elbow synovectomy and débridement provide predictable short-term pain relief [17]. Interestingly, the results do not necessarily correlate with the severity of the arthritis. The results do, however, deteriorate somewhat over time, drifting down from 90% success at 3 years to 70% success by 10 years as the synovitis recurs [18–20]. Elbow motion is not necessarily improved by synovectomy; only 40% of patients obtain better motion. A study comparing arthroscopic and open synovectomy demonstrated equivalent results with either technique if the preoperative arc of flexion is greater than 90 degrees [19]. For stiff rheumatoid elbows, arthroscopic synovectomy performed better than the open method did.

Total elbow arthroplasty is a reliable procedure for the rheumatoid patient with advanced elbow arthritis [21,22]. The Mayo Clinic has reported excellent results with a semiconstrained prosthesis [23], with pain relief in 92% of patients and an average arc of motion of 26 to 130 degrees, with 64 degrees of pronation and 62 degrees of supination. An outcomes study demonstrated good satisfaction of the patients, although the majority of patients continued to have some functional impairments, presumably due, in part, to rheumatoid involvement in other joints [24]. In spite of the excellent clinical results, the patient should be made aware that the complication rate for total elbow arthroplasty is significantly higher than that for the more conventional hip and knee replacements.

Potential Disease Complications

End-stage rheumatoid arthritis of the elbow can produce either severe stiffness or instability. Advanced primary arthritis invariably produces stiffness. Either outcome results in pain and limited function of the involved extremity. In addition, entrapment or traction neuritis of the ulnar nerve is not uncommon. Compressive injury to the posterior interosseous nerve from rheumatoid synovial hyperplasia has also been reported.

Potential Treatment Complications

The systemic complications of the disease-modifying agents used in treatment of rheumatoid arthritis are numerous and are beyond the scope of this chapter (see Chapters 34 and 41). Analgesics and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs have well-known side effects that most commonly affect the gastric, hepatic, and renal systems. Intra-articular steroid injections introduce the risk of iatrogenic infection and may produce transient chondrocyte damage.

Potential surgical complications include infection, wound problems, neurovascular injury, stiffness, recurrent synovitis, triceps disruption, periprosthetic lucency, fracture, and iatrogenic instability. In the primary and post-traumatic osteoarthritic elbow, motion-improving procedures such as ulnohumeral arthroplasty do not halt the inevitable radiographic progression of the disease. Similarly, synovectomy of the rheumatoid elbow, even if it is successful in alleviating pain and synovitis, does not reliably prevent further joint destruction. Preoperative ulnar nerve symptoms can occasionally be made worse by surgery, and simultaneous ulnar nerve transposition should be considered in such patients when the preoperative range of motion is limited [11]. In an analysis of 473 consecutive elbow arthroscopies, major and temporary minor complications occurred in 0.8% and 11% of patients, respectively [8]. The most significant risk factors for development of temporary nerve palsies were rheumatoid arthritis and contracture.

With total elbow arthroplasty, wound healing problems, infection, triceps insufficiency, and implant loosening are the principal complications, occurring in approximately 5% to 7% of patients. As a result, most surgeons place lifelong restrictions on high-impact loading (no golf, no lifting of more than 10 pounds) to minimize the need for revision surgery.