CHAPTER 21. CONSTIPATION

Debra E. Heidrich

DEFINITION AND INCIDENCE

Constipation is an extremely common problem among palliative care patients. Patients with constipation often experience abdominal discomfort, cramping, and distention as well as nausea. Unresolved constipation leads to fecal impaction—a large amount of hard, dry feces that accumulates in the rectum and sigmoid colon and cannot be evacuated—and, potentially, obstipation, a functional bowel obstruction from constipation or impaction. Patients who associate constipation with the use of opioids or other medications may discontinue or decrease these medications, leading to uncontrolled symptoms and additional discomfort. As such, proper and timely management is crucial.

In the general population, the incidence of constipation may range from 5% to 20%. Studies of patients with advanced cancer and other terminal illness indicate the incidence of constipation ranges from 32% to 87% (Potter, Hami, Bryan et al., 2003; Sykes, 1998, 2004; Wirz & Klaschik, 2005). Some of this variation is likely due to the proportion of the study population using opioids. However, Sykes (1998) reported that 64% of hospice patients who were not receiving opioid analgesia had constipation. Other factors contributing to the range in the reported incidence of constipation include variations in the primary diagnoses, ages, and settings of the study participants. In addition, constipation is likely underdiagnosed (Sykes, 2004).

A general definition of constipation is the passage of small amounts of hard, dry stool less often than three times a week (Folden, Backer, Maynard et al., 2002). However, constipation has different meanings to different people (Mercadante, 2002; Sykes, 2004). Patients may report constipation if feces are hard and dry; if there is straining, difficulty, or discomfort in expelling stool; or if stools are less frequent than normal for them.

ETIOLOGY AND PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Normal bowel function requires the interaction of many body systems to break down food, allow proper absorption and transport of fluids and nutritional elements, and move the remaining food residue through the gastrointestinal (GI) tract to form feces for excretion. These processes are mediated by an interaction of the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems affecting motor, secretory, and endocrine activities (Carroll, 2005). The urge to defecate occurs when the rectum fills with stool. The voluntary relaxation of the external sphincter allows for defecation (Carroll, 2005). Alterations in any of these body systems or physiological processes negatively affect bowel functioning.

Many factors contribute to constipation in patients with advanced progressive illnesses, including the following.

Immobility

Patients with little to no activity cannot maintain normal bowel motility. Defecation requires upright posture and strong abdominal, diaphragmatic, and anal muscles (Folden et al., 2002). Individuals with generalized fatigue and weakness and those who cannot sit on a toilet or bedside commode are at great risk for constipation.

Diet and Hydration

Patients with terminal illnesses often find it difficult to eat and drink adequate amounts of food and fluid for a variety of reasons (see Chapter 20, Cachexia and Anorexia). Low-residue diets may lack the necessary bulk to propel the feces through the bowel. The resulting constipation worsens when there is inadequate fluid intake; as a result, more water is reabsorbed from the colon and hard, dry stool is produced.

Medications

▪ Opioids bind with opioid receptors in the GI tract, leading to (1) a decrease in intestinal, gastric, biliary, and pancreatic secretions, (2) a decrease in propulsive movements due to inhibition of acetylcholine release that relaxes the intestinal musculature, and (3) an increase in internal anal sphincter tone. The net effects of stimulation of the GI opioid receptors are a decrease in stool hydration and an increase in transit time in the colon, leading to constipation (Klaschik, Nauck, & Ostgathe, 2003; Sykes, 2004). Some opioids cause more constipation than others and some individuals seem to be more sensitive to the constipating effects of opioids than others. In a study of laxative use in 49 subjects on opioids, Mancini, Hanson, Neumann et al. (2000) noted that patients on morphine required more laxative than did those on methadone. Another study of 1836 patients receiving long-acting opioid therapy found that those using transdermal fentanyl had less constipation than those using controlled-release oxycodone or controlled-release morphine (Staats, Markowitz, & Schein, 2004).

▪ Anticholinergic drugs and other medications with anticholinergic effects (e.g., tricyclic antidepressants, phenothiazines, some antipsychotics, antiparkinsonian agents) slow peristalsis, increasing the risk of constipation.

▪ Other medications contributing to constipation include antacids containing calcium or aluminum, iron supplements, diuretics, antihypertensives, calcium channel blockers, and antidiarrheal medications (Hodgson & Kizior, 2004; Sykes, 2004). In addition, overuse of laxatives can lead to a weakening of the defecation reflexes, inhibiting natural bowel functioning.

Chemical Imbalances

▪ Hypercalcemia. A high serum calcium level likely depresses the contractility of the muscle walls of the GI tract. In addition, polyuria with hypercalcemia may lead to dehydration, further contributing to constipation (Bower & Cox, 2004; White, 2005).

▪ Hypokalemia can also lead to constipation or, in some situations, paralytic ileus, which probably results from the unresponsiveness of hyperpolarized GI smooth muscle (White, 2005). A common cause of hypokalemia is administration of thiazide diuretics without potassium replacement.

Pressure and Compression of Intestines

Cancer patients with tumor in the abdomen require more laxatives than do other patients on opioid therapy (Mancini et al., 2000). Patients with ascites, abdominal or pelvic tumors, or enlarged lymph nodes are at risk for abnormalities in digestion and elimination. A partial bowel obstruction from tumor growth either inside the intestinal lumen or due to compression from outside the lumen slows motility, contributing to constipation and potentially leading to a complete obstruction (Sykes, 2004). Patients with a history of abdominal surgery are also at risk for the development of adhesions. These adhesions can decrease intestinal lumen size, interfering with transit time in the bowel; partial and complete bowel obstructions are possible.

Changes in the Innervation of the Gastrointestinal Tract

Constipation has been noted in many patients with motor disorders, such as spinal cord lesions and neurological diseases. This constipation is likely the result of visceral neuropathy and a disturbance in the nerve supply of the colon that slows the colonic transit time. In addition, patients who have neurological diseases may experience failure of the puborectalis and anal sphincter muscles to relax, causing intractable constipation (Mercadante, 2002). The innervation of the intestinal tract can also be interrupted by surgery. A history of abdominal surgery provides helpful information for assessing constipation. Neuropathy is a complication of some cancer chemotherapy agents, in particular, the vinca alkaloids. Although constipation is a well-documented side effect of these medications in patients undergoing active treatment, the long-term effects are not clear. Patients who received high cumulative doses of the vinca alkaloids may be at risk for persistent constipation (Mercadante, 2002).

The elderly may experience sensory changes affecting bowel functioning. In particular, rectal insensitivity may lead to a decrease in the urge to defecate (Sykes, 2004). When the urge to defecate is ignored, the anal muscles become weakened, resulting in a risk for constipation and impaction.

Psychosocial Concerns

Under conditions of fear, anxiety, stress, and depression, epinephrine is released as a sympathetic stress response. Epinephrine decreases peristalsis, leading to a risk for constipation. However, the stress response can also increase intestinal mucus formation and cause pain and cramping. Thus, some patients, when stressed, have alternating bouts of diarrhea and constipation. Patients who are embarrassed about using bedpans or bedside commodes may ignore the need to defecate to preserve their privacy. In addition, those who are confused, lethargic, weak, or in pain may not respond to the defecation reflex. As noted, this inattention to the urge to defecate can result in weakened anal muscles.

ASSESSMENT AND MEASUREMENT

Constipation is identified via patient report of infrequent or absent bowel movements, difficulty or pain in defecating, incomplete defecation, or hard, dry stool. Although patients may associate symptoms such as abdominal pain, bloating, flatulence, nausea, malaise, and headache with constipation, these symptoms are not specific to constipation (Sykes, 2004). Stool amount, consistency, and frequency and the length of time since the last bowel movement are important assessment data.

It is important to identify the patient’s definition of constipation. Some may report constipation if a day passes without a bowel movement despite the lack of other symptoms. This may or may not indicate actual constipation. “Normal” bowel habits can range from a bowel movement one to three times a week to daily or several daily bowel movements.

HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

When performing the history and physical examination, be sensitive to the fact that many people are at least uncomfortable, if not extremely embarrassed, by questioning about bowels and bowel functioning. Maintain an environment as conducive to patient privacy as possible during history taking and examination.

General Assessment

▪ Patient’s medical history and presence of any disease affecting bowel function

▪ Fluid and food intake, including amounts and types of fluids and food

▪ Hydration status: skin turgor, condition of mucous membranes, urinary output, orthostatic blood pressure measurements

▪ Current medications, especially any opioids, tricyclic antidepressants, anticholinergics, sedatives, antiemetics, antipsychotics, antihypertensives, antacids, and diuretics

▪ Activity level and ability to use a toilet or bedside commode

History Related to Complaint of Constipation

▪ Normal bowel patterns and history of any constipation problems

▪ Patient’s definition or description of “constipation”

▪ Date of the last bowel movement as well as the amount, color, and consistency of stool

▪ Any discomfort or bleeding with bowel movements

▪ Interventions the individual uses or has used to prevent or relieve constipation, including medications, enemas, or any special teas, juices, or foods

▪ Patient’s evaluation of the effectiveness or side effects of these interventions

▪ Any use of manual manipulation, such as the application of anal pressure or digital removal of stool

Gastrointestinal Assessment

▪ Reports of abdominal pain or cramping

Note: The pain of constipation may be mistaken for pain related to the disease and “treated” with additional opioids instead of treating the problem of constipation (Sykes, 2004). Do not withhold opioids from patients with pain and constipation; perform a thorough assessment to determine the potential cause of pain and treat it appropriately.

▪ Reports of nausea or vomiting

▪ Abdominal assessment

Distention

Bowel sounds

Increased activity occurs in early intestinal obstruction

Decreased or absent bowel sounds, which may indicate ileus or peritonitis

High-pitched tinkling sounds, indicating fluid and air under tension in a dilated bowel

Rushes of high-pitched sounds with abdominal cramping, which indicate intestinal obstruction (Bickley & Szilagyi, 2003)

Masses and areas of tenderness on palpation

Ascites or trapped air that may be noted with percussion

Rectal Examination

▪ Inspect the rectum for fissures, tears, hemorrhoids, fistulas, or tumors.

▪ Perform a digital examination to identify stool or tumors in the rectum.

▪ Avoid digital examination if the patient is neutropenic or thrombocytopenic or has known tumors.

Psychoemotional Assessment

▪ Assess the patient’s ability to maintain privacy for toileting.

▪ Evaluate the patient’s stress and anxiety level.

▪ Assess for confusion or dementia.

DIAGNOSTICS

As with all symptom evaluation in palliative care, radiographic and laboratory procedures should be performed only when confirmation of the underlying problem will change the course of treatment. If the cause of constipation can be identified on the basis of the medical diagnosis, treatments, or other presenting symptoms, confirmation by radiography or blood work may not be necessary to determine an appropriate course of treatment.

▪ An abdominal film may differentiate between constipation and obstruction (Mercadante, 2002). It is performed only if there is persistent doubt and is rarely necessary (Sykes, 2004). (See Chapter 19, Bowel Obstruction.)

▪ Barium studies may be useful in distinguishing between a paralytic ileus and mechanical obstruction (Mercadante, 2002).

▪ Radiographic studies of colonic transit time, although useful in some settings to determine which areas of the bowel are not functioning, are rarely well tolerated by patients with advanced illness (Mercadante, 2002; Sykes, 2004).

▪ Serum electrolyte levels will identify hypercalcemia or hypokalemia.

INTERVENTION AND TREATMENT

Prophylactic Interventions

The goal of care is to prevent constipation rather than to wait for it to develop. The appropriateness of the following interventions to prevent constipation is determined by the individual’s performance status, mental status, and ability to eat and drink.

▪ Encourage activity to stimulate natural bowel functioning when pain and fatigue do not interfere. Encourage range of motion and isometric exercises to maintain some muscle strength for patients who are unable to get out of bed (Folden et al., 2002).

▪ Encourage adequate oral fluid intake. The 1.5 to 2 liters per day required to maintain good hydration is often not tolerated by patients with advanced illnesses.

▪ Encourage patients to drink warm fluids (e.g., coffee, teas, juices) with or after meals because they stimulate the bowel. Be aware that caffeine may have a mild diuretic effect.

▪ Encourage foods high in bulk and fiber for patients with normal appetites (Folden et al., 2002).

The amount of fiber required to treat constipation is often not tolerated by patients with advanced illness, and dietary changes alone are generally not sufficient. The dietary emphasis for the terminally ill should be on identifying patient likes and desires versus providing fiber and bulk (Sykes, 2004).

▪ Maintain a consistent time for defecation, usually after a meal (Folden et al., 2002).

▪ Instruct caregivers to respond quickly to patient requests to defecate.

▪ Encourage the use of a toilet or bedside commode so the patient can maintain an upright position. If the patient is unable to sit when defecating, a left-side-lying position is recommended (Folden et al., 2002).

▪ Allow the patient privacy during toileting. Use of a raised toilet seat and bathroom handrails increases the individual’s independence and promotes safety and privacy (Folden et al., 2002).

▪ Make appropriate changes in medications that are contributing to constipation.

Discontinue nonessential medications.

When the offending medication is required for symptom control, consider a change to a medication with the potential for fewer side effects. For example, as noted earlier, methadone or fentanyl may be less constipating for some, but not necessarily all, individuals, and the secondary amine tricyclic antidepressants (e.g., desipramine and nortriptyline) may be less constipating than the tertiary amine tricyclic antidepressants (e.g., amitriptyline) (Lussier & Portenoy, 2004).

Laxatives

Despite the maximal use of prophylactic interventions, many patients with terminal illness require laxatives to treat and prevent constipation (Sykes, 2004). There is little research to guide the appropriate choice of laxatives or combinations of laxatives. Consider the characteristics of the patient’s constipation when selecting a laxative: hard stool requires a softener; soft, difficult-to-pass stool requires a stimulant (Klaschik et al., 2003). Likewise, the patient’s response to the laxative regimen will guide titration or changes in the doses and types of laxatives used: too much softening leads to fecal leakage and incontinence; too much stimulant causes abdominal cramping (Sykes, 2004).

Patients for whom the cause of constipation cannot be eliminated will require routine use of laxatives. Low doses of laxatives are best given at night; higher doses may need to be divided, usually into morning and evening doses. Patients receiving opioid therapy almost always require the routine use of a combination of stimulant and softening laxatives.

Laxative agents differ according to active ingredients and mechanism of action. The following discussion outlines the mechanisms of action for the various types of laxatives, examples of each type, and starting doses.

Lubricant Laxatives

Lubricant laxatives penetrate the stool to soften it and to lubricate the surface of the stool. In addition, they prevent some absorption of water from the intestinal tract, which also helps to keep the stool soft (Klaschik et al., 2003; Sykes, 2004). Lubricant laxatives are less palatable than are many other types of laxatives. Also, because of the risk for aspiration pneumonia, oral liquids are avoided in pediatrics and in patients with dysphagia. The onset of action is approximately 6 to 8 hours after oral administration. Mineral oil (e.g., Fleet Mineral Oil Enema, Liqui-Doss, Milkinol) is the most frequently used lubricant laxative. The oral dose is 15 to 30 ml per day. Mineral oil enemas are generally 4 ounces. There are many home remedies that use a lubricating substance, such as petroleum jelly. For example, some hospice programs recommend two frozen 1/2-teaspoon-size balls of petroleum jelly (rolled in sugar to make them more palatable) for constipation. This intervention is usually reserved for patients who do not get a good response from other laxatives and enemas. Note that there is no research on this intervention.

Bulk-Forming Laxatives

Bulk-forming laxatives provide material that resists bacterial breakdown (nondigestible methylcellulose, psyllium, or polycarbophil), which enhances stool bulk. This increases the volume of the stool, dilating the intestinal wall, and stimulates bowel motility. These laxatives also provide substrates for bacterial growth, promoting increased transit time via fermentation (Klaschik et al., 2003; Sykes, 2004). Because of the water-binding capacity of these products, patients must take them orally with 6 to 8 ounces of water or juice and maintain adequate overall fluid intake—at least 1.5 to 2 liters per day. Bulk-forming laxatives should be avoided if fluid intake is not adequate or if there is a suspicion of intestinal stricture or bowel obstruction (Waller & Caroline, 2000). Most bulk-forming laxatives take 12 to 72 hours to produce results. Examples include the following:

▪ Methylcellulose powder (e.g., Citrucel), 3 to 4 g/day orally

▪ Psyllium (e.g., Natural Fiberall, Metamucil), 3 to 4 g/day orally

▪ Polycarbophil (e.g., Fiberall, FiberCon), 3 to 4 g/day orally

Emollients and Surfactants

The detergent action of emollient laxatives increases water penetration into fecal matter (Sykes, 2004). They produce softer, moister fecal material. These laxatives are rarely sufficient alone for opioid-induced constipation since the longer transit time caused by the opioids counteracts the benefits of the softeners. Time to action is 12 to 72 hours after administration. Docusate sodium (Colace) 100 to 300 mg/day orally is the most commonly used emollient laxative.

Saccharine Laxatives

The saccharine laxatives create an osmotic gradient in the lumen and prevent water absorption from the small intestine. The oral doses required for opioid-induced constipation often lead to bloating, cramping, and diarrhea (Klaschik et al., 2003; Sykes, 2004). These laxatives pull water from the body and can lead to dehydration. However, glycerin suppositories act in the distal colon and have minimal side effects. Oral agents take 12 to 72 hours to work; suppositories stimulate bowel movements in 15 to 30 minutes. Examples include the following:

▪ Lactulose (e.g., Cephulac, Duphalac), 15 ml twice daily orally

▪ Sorbitol, 30 ml/day orally

▪ Glycerin, one suppository, per rectum

Saline Osmotic Laxatives

The poorly absorbed salts of saline laxatives produce an immediate osmotic gradient. In addition to the influx of fluids secondary to osmosis, the magnesium salts may stimulate the secretion of cholecystokinin, which stimulates motility (Sykes, 2004). Again, these medications pull in body fluids, leading to the potential for dehydration (Klaschik et al., 2003). Oral preparations take 30 minutes to 3 hours to work. Saline enemas are generally effective within 15 minutes. Examples include the following:

▪ Magnesium citrate, 120 to 240 ml/day orally

▪ Magnesium hydroxide (e.g., Milk of Magnesia), 2 to 4 g/day orally

▪ Sodium biphosphate–sodium phosphate (e.g., Fleet Enema, one daily per rectum; Fleet Phospho-Buffered Saline Soda, 20 to 30 ml/day orally)

Macrogol Osmotic Laxatives

The macrogol laxatives bind with the oral fluids with which they are administered and hydrate harden stool, leading to an increase in stool volume and dilation of the bowel wall, which triggers the defecation reflex (Klaschik et al., 2003). These medications were originally marketed for use in high doses as bowel-cleansing agents before GI procedures; in smaller doses, they are used to treat constipation. Because microgols bind only with the orally administered fluids, water is not drawn from the body. Therefore, these medications have a lesser potential for causing dehydration than the other osmotic agents. Also, because these substances do not undergo fermentation in the GI tract like saccharine does, there is no gas production and its associated discomforts. When used to treat constipation, it may take 2 to 3 days for the initial effect, but with regular use, the frequency of bowel movements is usually once per day (Klaschik et al., 2003). Studies show polyethylene glycol is effective for constipation in the palliative care setting (Wirz & Klaschik, 2005). Some programs use these agents as the drug of choice for treating opioid-induced constipation (Klaschik et al., 2003). However, more research is needed to determine if they are truly a better than combinations of standard stimulants plus laxatives. An example of a macrogol is polyethylene glycol (e.g., MiraLax), 17 g (approximately 1 heaping tablespoon) in at least 125 ml of water.

Stimulant Laxatives

Stimulant laxatives increase GI motility by stimulating the myenteric plexus of the intestinal smooth muscle (Sykes, 2004). The absorption of water and electrolytes in the colon is reduced with the use of stimulant laxatives. Stimulants may cause cramping, electrolyte disturbances, and dehydration. Castor oil is a very potent stimulant and is rarely used because of the negative side effects. Aloe extracts and cascara sagrada are not recognized as safe and effective laxatives by the Food and Drug Administration (Department of Health and Human Services, 2002).

Depending on availability, stimulant laxatives may be given by mouth as pills or liquids or by rectum as suppositories or enemas. In addition to the effect of the medication being given, the use of the rectal route may initiate defecation by stimulation of the anocolonic reflex (Sykes, 2004).

The rectal route is considered second-line therapy for use when the oral route is insufficient. This route of administration is not pleasant for the patient or the caregivers giving the medication. All effort should be made to maintain routine bowel movements with oral medication. Examples of stimulant laxatives, with starting doses, include the following:

▪ Senna (Senokot, Senolax), 15 mg/day orally (Senna teas are also available at some health food stores)

▪ Bisacodyl (oral: Correctol, Dulcolax, Feen-A-Mint, 10 mg/day orally; suppository: Bisco-Lax, Fleet Laxative)

Combination Laxatives

Combining two or more types of laxatives with different mechanisms of action may produce synergistic effects. A combination of a stimulant and a softener is recommended for patients receiving opioid therapy; others may benefit from this combination as well. There are several combination laxatives available on the market, although the same effect can be obtained by taking the two medications separately. Examples of combination laxatives include the following:

▪ Bisacodyl–docusate sodium (Modane Plus)

▪ Senna–docusate sodium (Senokot-S; Peri-Colace)

Other Medications with Laxative Effects

Prokinetic agents have been investigated for the treatment of constipation. The subcutaneous infusion of metoclopramide is noted to be effective in the treatment of narcotic bowel syndrome (Bruera, Brenneis, Michaud et al., 1987). Further investigations comparing metoclopramide with standard laxative therapies are needed to determine its role as an oral laxative (Sykes, 2004).

Opioid-induced constipation has also been treated with opioid antagonists. The goal is to antagonize peripheral opioid receptors in the GI tract without antagonizing the central opioid receptors—that is, reversal of constipation without reversal of analgesia. Naloxone given orally was the first opioid antagonist investigated for this use. It was believed that the first-pass hepatic metabolism of naloxone would leave very little available to antagonize central opioid receptors (Sykes, 2004). However, in the few limited studies, a high proportion of subjects either experienced withdrawal or required increased opioid doses to control pain (Liu & Wittbrodt, 2002). Currently, methylnaltrexone, a derivative of the opioid antagonist naltrexone, is being investigated for use in treating opioid-induced constipation. Methylnaltrexone does not cross the blood-brain barrier, so it should not induce a withdrawal response. Initial studies are promising (Yuan, Foss, O’Connor et al., 2000; Yuan, 2004). However, more research is needed to evaluate effectiveness and to compare it with other treatments for constipation.

Guidelines for Using Laxatives

Unfortunately, there is no “gold standard” for the management of constipation. Each patient’s situation is different in terms of the factors contributing to constipation, and these contributing factors may change over time in the same patient. The most common error in the management of constipation is the failure to titrate laxatives to an effective dose (Ogle & Hopper, 2005).

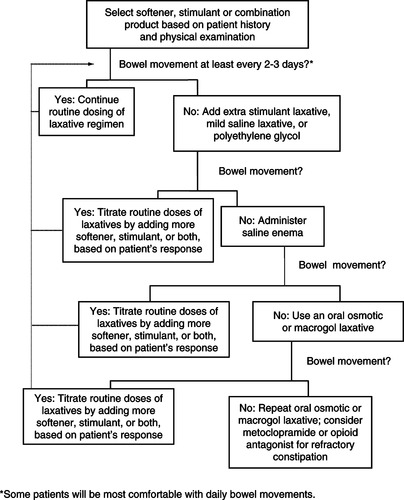

Before initiating laxative therapy, rule out bowel obstruction and then disimpact the bowel, if necessary. Begin laxative therapy as outlined in Figure 21-1. The initial selection of the laxative regimen is based on the patient’s medical history, current medications, and physical examination. If there is soft stool in the rectum that is difficult to eliminate, begin with a stimulant laxative; if there is a small amount of hard, dry stool in the rectum, initiate therapy with an emollient laxative; if there is little to no stool in the rectum, the patient may require a combination of a softener and a laxative. Patients receiving opioids require a combination of a stimulant laxative and an emollient softener.

|

| Figure 21-1 |

The goal is for the patient to have a regular, comfortable bowel movement. Assess the usual frequency of bowel movements to determine what is normal for an individual; often this will be daily, but for some patients “normal” may be up to 2 to 3 days between bowel movements. Note that if an additional intervention is required to produce a bowel movement, the routine doses of softener and stimulant laxatives must be adjusted. If an “extra” intervention is required every 2 days, the regimen should be changed. Additional adjustments in laxatives will be required as the disease progresses, due to changes in food and fluid intake, use of medications that affect the bowel, changes in activity level, and decline in muscle strength.

PATIENT AND FAMILY EDUCATION

Patients and families require information on the importance of reporting constipation, the appropriate use of the prophylactic interventions, and the appropriate use of laxatives.

▪ Discuss the importance of reporting bowel functioning, including frequency, amount, and consistency of stools and any discomfort associated with defecation, to the health care team.

▪ Teach patients who are able to do so to participate in exercise activities or isometric abdominal and pelvic exercises.

▪ Encourage the use of warm liquids with meals to stimulate bowel functioning.

▪ Discuss the importance of responding immediately to the urge to defecate with both the patient and the caregivers.

▪ Discuss the benefit of maintaining an upright position for defecation; encourage the use of a toilet or bedside commode.

▪ Caregivers may require instruction on proper transfer techniques for assisting the patient out of a bed or chair to a bedside commode.

▪ Teach the appropriate dosing and schedule of laxative medications. Those that require 6 hours or longer to work are best dosed at night.

▪ Discuss the importance of avoiding the bulk-forming laxatives for patients taking opioids and for those whose fluid intake is limited.

EVALUATION AND PLAN FOR FOLLOW-UP

The effectiveness of the interventions to manage constipation is determined by reassessing the patient’s bowel status. Ask about the frequency, amount, and consistency of stools and about any discomfort or difficulty passing stool. It is also important to ask about the effectiveness of laxatives to determine appropriate changes in the plan of care.

Assessment of bowel status must be a part of the ongoing, routine evaluation of the patient to determine if the prescribed regimen continues to be effective over the course of the patient’s care. Patients with advanced illnesses will experience changes in the disease process, fluid intake, activity level, and prescribed medications that will affect the bowels and necessitate modifications in the care plan.

Mr. R. has metastatic lung cancer and a history of congestive heart failure. He received treatment with combination chemotherapy 6 months ago, and he tolerated it well. However, the cancer progressed and he was referred for home hospice care. Mr. R. has a poor appetite and states that he feels nauseated if he eats more than a few bites of food. He keeps a 1-quart pitcher of water at his bedside and reports drinking the entire quart over the course of a day. He also drinks a small glass of orange juice with breakfast. He is able to walk to the bathroom with the assistance of his wife. Mr. R. reports that he has not had a bowel movement in 3 days despite taking Metamucil every day. He is complaining of abdominal bloating and cramping.

Mr. R.’s medications include the following: sustained-release oxycodone 40 mg twice daily, immediate-release oxycodone 10 mg every 1 to 2 hours for breakthrough pain or dyspnea, ibuprofen 400 mg four times daily, furosemide 40 mg/day, and digoxin 0.125 mg/day.

On physical examination, the clinician notes that there is no stool in the rectum and that bowel sounds are hyperactive. The constipating effects of the opioids and the need to use both a stimulant and a softener laxative are discussed with the patient. The clinician also explains that the bulk-forming laxatives are not a good choice at this time because these medications may actually cause constipation if fluid intake is less than 8 cups each day. The patient is instructed to take magnesium citrate, 120 to 240 ml over ice, as tolerated. Two hours later, Mr. R. reports that he has passed a small amount of hard feces and feels there is more stool in the rectum. A bisacodyl (Dulcolax) suppository is administered to empty the rectum of stool. The patient is then started on a regimen of sennosides: 8.6 mg and docusate sodium 50 mg (Peri-Colace, Senokot-S), two tablets at bedtime. He also is instructed to take magnesium hydroxide (Milk of Magnesia), 30 ml at bedtime, if more than 2 days pass without a bowel movement and to inform the clinician if he needs to use the Milk of Magnesia more than once a week.

This regimen works well for Mr. R. for about a month. Then he reports needing to take the Milk of Magnesia every 2 days. Mrs. R. also states that the patient gets short of breath walking to the bathroom and, in general, his activity level has decreased. The clinician instructs the patient to increase the Peri-Colace to three tablets at bedtime. On physical assessment, the clinician notes that the patient is slightly dehydrated with no peripheral edema and the clinician instructs Mr. R. to discontinue the furosemide. The clinician also discusses the energy-saving benefits of a bedside commode and, with the patient’s and wife’s permission, orders one for the patient.

Mr. R. continued to have bowel movements of soft, formed stool every 1 to 2 days up until 3 days ago. He is now bed-bound, taking in only sips of fluids, and having some difficulty swallowing pills. The Peri-Colace is discontinued. The clinician monitors for bowel sounds, abdominal distention, and the presence of stool in the rectum. The following day, some stool is noted in the rectum, and the clinician administers a Dulcolax suppository with good results. Mr. R. dies peacefully 2 days later, with no sign of abdominal distention or discomfort.

REFERENCES

Bickley, L.S.; Szilagyi, P.G., The abdomen, In: (Editors: Bickley, L.S.; Szilagyi, P.G.) Bates’ guide to physical examination and history taking8th ed. ( 2003)Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, pp. 317–366.

Bower, M.; Cox, S., Endocrine and metabolic complications of advanced cancer, In: (Editors: Doyle, D.; Hanks, G.; Cherny, N.I.; et al.) Oxford textbook of palliative medicine3rd ed. ( 2004)Oxford University Press, New York, pp. 687–702.

Bruera, E.; Brenneis, C.; Michaud, M.; et al., Continuous subcutaneous infusion of metoclopramide for treatment of narcotic bowel syndrome, Cancer Treat Rep 71 (11) ( 1987) 1121–1122.

Carroll, R.G., Anatomy and physiology review: The elimination system, In: (Editors: Black, J.M.; Hawks, J.H.) Medical-surgical nursing: clinical management for positive outcomes7th ed. ( 2005)Elsevier Saunders, St. Louis, pp. 766–774.

Department of Health and Human Services, Status of certain additional over-the-counter drug category II and III active ingredients, Federal Register 67 (90) ( 2002) 31125–31127.

Folden, S.L.; Backer, J.H.; Maynard, F.; et al., Practice guidelines for the management of constipation in adults. ( 2002)Association of Rehabilitation Nurses, Glenview, Ill..

Hodgson, B.B.; Kizior, R.J., Nursing drug handbook 2004. ( 2004)Saunders, St. Louis.

Klaschik, E.; Nauck, F.; Ostgathe, C., Constipation—Modern laxative therapy, Support Care Cancer 11 (11) ( 2003) 679–685.

Liu, M.; Wittbrodt, E., Low-dose oral naloxone reverses opioid-induced constipation and analgesia, J Pain Symptom Manage 23 (1) ( 2002) 48–53.

Lussier, D.; Portenoy, R.K., Adjuvant analgesics in pain management, In: (Editors: Doyle, D.; Hanks, G.; Cherny, N.I.; et al.) Oxford textbook of palliative medicine3rd ed. ( 2004)Oxford University Press, New York, pp. 349–378.

Mancini, I.L.; Hanson, J.; Neumann, C.M.; et al., Opioid type and other clinical predictors of laxative dose in advanced cancer patients: A retrospective study, J Palliat Med 3 (1) ( 2000) 49–56.

Mercadante, W., Diarrhea, malabsorption, and constipation, In: (Editors: Berger, A.; Portenoy, R.; Weissman, D.) Principles and practice of palliative and supportive oncology2nd ed. ( 2002)Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, pp. 233–249.

Ogle, K.S.; Hopper, K., End-of-life care for older adults, Primary Care: Clin Office Pract 32 (3) ( 2005) 811–828.

Potter, J.; Hami, F.; Bryan, T.; et al., Symptoms in 400 patients referred to palliative care services: Prevalence and patterns, Palliat Med 17 (4) ( 2003) 310–314.

Staats, P.S.; Markowitz, J.; Schein, J., Incidence of constipation associated with long-acting opioid therapy: A comparative study, South Med J 97 (2) ( 2004) 129–134.

Sykes, N., Constipation and diarrhoea, In: (Editors: Doyle, D.; Hanks, G.; Cherny, N.I.; Calman, K.) Oxford textbook of palliative medicine3rd ed. ( 2004)Oxford University Press, New York, pp. 483–496.

Sykes, N.P., The relationship between opioid use and laxative use in terminally ill cancer patients, Palliat Med 12 (5) ( 1998) 375–382.

Waller, A.; Caroline, N.L., Handbook of palliative care in cancer. 2nd ed. ( 2000)Butterworth-Heinemann, Boston.

White, B., Clients with electrolyte imbalances, In: (Editors: Black, J.M.; Hawks, J.H.) Medical-surgical nursing: Clinical management for positive outcomes7th ed. ( 2005)Elsevier Saunders, St. Louis, pp. 223–245.

Wirz, S.; Klaschik, E., Management of constipation in palliative care patients undergoing opioid therapy: Is polyethylene glycol an option?Am J Hospice Palliat Care 22 (5) ( 2005) 375–381.

Yuan, C., Clinical status of methylnaltrexone, a new agent to prevent and manage opioid-induced side effects, J Support Oncol 2 (2) ( 2004) 111–117.

Yuan, C.; Foss, J.F.; O’Connor, M.; et al., Methylnaltrexone for reversal of constipation due to chronic methadone use: A randomized controlled trial, JAMA 283 (3) ( 2000) 367–372.