CHAPTER 20

Suprascapular Neuropathy

Definition

Suprascapular neuropathy is a demyelinating or axonal injury to the suprascapular nerve. Once considered a diagnosis of exclusion, suprascapular neuropathy is now becoming a well-recognized condition stemming from traction or compression of the nerve at some point along its course. Epidemiologic data are limited, but the prevalence of suprascapular neuropathy is reportedly between 12% and 33% in overhead athletes and between 8% and 100% in patients with massive rotator cuff tears [1].

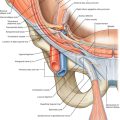

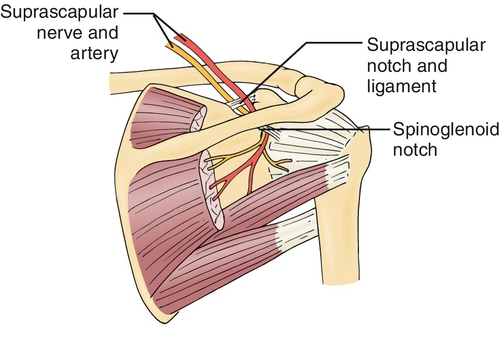

To understand the pathophysiologic mechanism, it is imperative to have a good knowledge of the anatomy (Fig. 20.1). The suprascapular nerve arises from the upper trunk of the brachial plexus and receives contributions mainly from the fifth and sixth cervical nerve roots, with variable contribution from the fourth cervical nerve root. It courses posterolaterally, deep to the trapezius and clavicle, on its way to the suprascapular notch. Here, it passes beneath the transverse scapular ligament to enter the supraspinous fossa. Within the supraspinous fossa, the suprascapular nerve sends two motor branches to the supraspinatus muscle and receives sensory branches from multiple surrounding structures, including the posterior aspect of the glenohumeral joint, the acromioclavicular joint, and the subacromial bursa. The nerve then courses inferolaterally around the lateral aspect of the scapular spine. This region is referred to as the spinoglenoid notch and is a common area of suprascapular nerve compression. Finally, the nerve enters the infraspinous fossa, where its terminal motor branches innervate the infraspinatus muscle.

The indirect course of the nerve as well as its passage through two notches makes it particularly vulnerable to injury. Static forms of compression or traction can stem from anatomic variations, particularly at the suprascapular notch, where the transverse scapular ligament can hypertrophy or ossify. At the spinoglenoid notch, compression is most frequently due to a space-occupying paralabral cyst that develops as a result of a labral tear [1].

Dynamic forms of suprascapular neuropathy are often seen in overhead athletes because of tightening of the spinoglenoid ligament during the overhead motion [2]. This leads to the so-called infraspinatus syndrome because only the infraspinatus is affected. Large rotator cuff tears can also cause a suprascapular neuropathy because the medially retracted muscle belly places a traction force on the nerve [3,4].

Less commonly, suprascapular neuropathy may result from shoulder girdle trauma or from iatrogenic injury as a complication of surgery. Three-dimensional mapping of operatively treated scapular fractures has shown extension of the fracture to the spinoglenoid notch in 22% of patients [5].

Symptoms

A range of symptoms may be associated with suprascapular neuropathy. Patients’ complaints are often similar to those of patients with other pathologic processes about the shoulder, including pain, weakness, and functional impairment. Some patients, however, may present only after recognizing painless atrophy. Suprascapular neuropathy is therefore difficult to diagnose on the basis of history alone. The pain, when it is present, can be poorly localized but is often located along the posterolateral shoulder and described as a deep, dull ache. This pain pattern coincides with the diffuse sensory contribution of the suprascapular nerve, as it carries sensory afferents from up to 70% of the shoulder [6]. For nontraumatic injuries, the onset is typically insidious and night pain is variable. Although it is less common, trauma can cause suprascapular neuropathy, and in this case, symptom onset is rapid.

For athletes, overhead sport-specific motions can intensify typical pain symptoms, and a decline in throwing velocity or hitting speed may be seen. Weakness is often described as a sense of fatigue during these activities.

Physical Examination

A complete physical examination of the shoulder is critical to identify a suprascapular nerve lesion and its underlying cause. Inspection may demonstrate atrophy in the supraspinatus or infraspinatus fossa. Atrophy of the supraspinatus may be difficult to visualize, given the bulk of the overlying trapezius. Isolated atrophy of the infraspinatus suggests compression of the nerve at the spinoglenoid notch. Palpation may elicit tenderness along the course of the nerve, particularly at the level of the suprascapular notch, within the supraspinous fossa or at the spinoglenoid notch. The tenderness may be enhanced with horizontal shoulder adduction, which tightens the spinoglenoid ligament. Strength testing may demonstrate weakness in abduction or external rotation. Weakness may be subtle because of compensatory muscle action. Other special tests should be performed to evaluate for labral disease, given its association with spinoglenoid notch cysts that can compress the suprascapular nerve. The examiner should also perform a thorough upper extremity neurovascular examination and evaluate the contralateral shoulder and cervical spine.

Functional Limitations

Functional limitations will vary significantly, depending on the patient’s activity level. As previously mentioned, overhead athletes may see a decrease in their pitching or throwing velocity or overhead swing speed. Strength deficits are particularly prevalent in volleyball players, up to 68% of whom have external rotation strength deficits in their hitting arm [7]. Weakness may be subtle and have limited effect on performance because of compensatory muscle action. In those patients with a proximal neuropathy affecting both the supraspinatus and infraspinatus, functional declines, especially with overhead activities, are more apparent.

Diagnostic Studies

A thorough history and physical examination can heighten suspicion for a suprascapular neuropathy and lead to the initiation of further testing. Whereas standard shoulder radiographs are most often unremarkable, a Stryker notch view can be helpful as it allows visualization of anatomic variations at the suprascapular notch. If bone variations are suspected, three-dimensional computed tomography is helpful to further delineate the anatomy and to plan interventions. Magnetic resonance imaging allows evaluation of the suprascapular nerve along its course, demonstrating points of tethering or compression. Rotator cuff edema or atrophy may be appreciated, giving a sense of the severity or chronicity of the nerve compression. Magnetic resonance arthrography is the diagnostic test of choice for labral disease and also will identify an associated spinoglenoid notch cyst. Ultrasonography can also identify rotator cuff disease and paralabral cysts.

Electrodiagnostic studies are the “gold standard” test for confirming the diagnosis of suprascapular neuropathy and grading the injury severity. A demyelinating injury is suggested by a prolonged distal motor latency with stimulation at Erb point and recording over the supraspinatus or infraspinatus. The presence of fibrillation potentials, positive sharp waves, increased motor unit amplitude or duration and polyphasia, and decreased recruitment pattern on needle electromyography suggest the presence of an axonal injury [8].

A diagnostic suprascapular nerve block can also assist with diagnosis of this disorder. The nerve block should be performed with ultrasound or fluoroscopic guidance to ensure accuracy. Temporary resolution of the patient’s symptoms in response to a suprascapular nerve block confirms the diagnosis of suprascapular neuropathy.

Treatment

Initial

An appropriate workup to accurately determine the cause and location of the suprascapular nerve injury is imperative as treatment strategies will vary according to the precise location and cause of the pathologic process. In the absence of an identified space-occupying lesion, such as a paralabral cyst, the first line of treatment is nonoperative. Patients should be instructed to avoid repetitive overhead activities or other exacerbating arm positions. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or acetaminophen can be used for pain relief. As with most shoulder-related disease, physical therapy plays an important role in nonoperative management.

Rehabilitation

Physical therapy has been demonstrated to be particularly effective when injury to the nerve is the result of a dynamic process, such as in overhead athletes. Ferretti and coworkers successfully treated 35 of 38 (92%) competitive volleyball players with isolated atrophy of the infraspinatus, and although the atrophy remained unchanged at long-term follow-up, the patients were asymptomatic [9]. Early rehabilitation should focus on flexibility of the scapular protractors and elevators, such as the pectoralis minor and superior belly of the trapezius. Strengthening should include the scapular stabilizers, with particular attention to the rhomboideus major and minor, inferior and middle bellies of the trapezius, and serratus anterior. The rotator cuff should also be strengthened, with a focus on the external rotators. Proprioceptive exercises improve shoulder stability and neuromuscular control. The exercise program should initially avoid positions of abduction and external rotation and gradually progress to exercises that enter this range of motion as the patient’s symptoms resolve. The final phase of rehabilitation should incorporate sports-specific training in preparation for return to sports. On completion of the final phase of supervised rehabilitation, the patient should be transitioned to a home exercise program to maintain the therapeutic gains.

Procedures

Procedures for management of suprascapular neuropathy typically serve a diagnostic purpose or provide temporary palliation. Suprascapular nerve blocks, as previously mentioned, can help localize the pain source. The suprascapular nerve can be blocked at the suprascapular notch or spinoglenoid notch. Because of the deep location and sensitive nature of the suprascapular nerve, image guidance (e.g., fluoroscopy or ultrasound) should be used in performing a suprascapular nerve block.

If a patient has a paralabral cyst causing suprascapular nerve compression in the spinoglenoid notch, an ultrasound-guided spinoglenoid notch cyst aspiration can be performed. However, this procedure frequently provides only temporary relief as the underlying pathologic change leading to the cyst (i.e., glenoid labral tear) is not addressed by this procedure [10]. Patients with chronic shoulder pain refractory to other treatments may respond to radiofrequency ablation of the suprascapular nerve.

Surgery

In the setting of failed nonoperative management, surgical intervention has been shown to provide effective pain relief and restoration of function in most patients [11]. Optimal surgical timing and approach are ongoing areas of debate. The goal of surgery is direct or indirect decompression of the nerve. For isolated suprascapular neuropathy, direct decompression can be achieved through open or arthroscopic means. The nerve is released at the suprascapular or spinoglenoid notch, depending on the cause. Some authors have advocated for routine release of both the transverse scapular ligament and spinoglenoid ligament to optimize the likelihood of a full neurologic recovery [12,13]. When underlying disease, such as a paralabral cyst or rotator cuff tear, is present, debate exists as to whether indirect decompression through addressing the primary pathologic process is sufficient to alleviate the neuropathy or whether concomitant direct nerve decompression is also necessary [1,12,13]. Further research is required to answer this question.

Potential Disease Complications

Ongoing compression of the suprascapular nerve could lead to permanent muscle weakness and progressive shoulder dysfunction that is usually not reversible when atrophy is significant. Given the role of the supraspinatus and infraspinatus in stabilizing the humeral head within the glenoid, one could speculate that rotator cuff arthropathy would be the end-result of long-term suprascapular neuropathy. It has been suggested that earlier surgical decompression may improve the likelihood for restoration of full muscle strength and normalization of shoulder function [11].

Potential Treatment Complications

Patients who are treated with mild oral analgesics such as acetaminophen and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are at risk for complications associated with these medications, such as liver or renal toxicity and peptic ulcer disease. Suprascapular nerve blocks can result in direct trauma to the suprascapular nerve. The complex anatomy of the suprascapular nerve places it at risk for injury during any surgical approach. Injuries can include nerve traction and nerve laceration. Ongoing pain, continued muscle atrophy, or recurrence can occur despite attempts at treatment.