Section 20 Psychiatric Emergencies

20.1 Mental state assessment

Epidemiology

Recent estimates place mental health disorders as one of the three leading causes of total burden of disease and injury in Australia, alongside cancer and cardiovascular disease.4,5,6 In middle age, it is the leading cause of non-fatal disease burden in the Australian population. There is no doubt that mental health disorders have a high prevalence, are disabling and are high cost in both human and socioeconomic terms.4,5

In terms of disability, it has been estimated that having moderate to severe depression is the equivalent of having congestive cardiac failure,6 chronic severe asthma or chronic hepatitis B.5 Severe post traumatic stress syndrome was comparable to the disability from paraplegia and severe schizophrenia was comparable to quadriplegia, in terms of disability.5 Over the last 10 years emergency department (ED) presentations have risen 8% in the USA, whereas mental health presentations for the same time period have risen 38%, contributing significantly to ED overcrowding.7 This trend has been mirrored in Australia.

The Australian Institute of Health and Welfare report into Mental Health Services in 2007 estimated that there were over 190 000 occasions of service to Australian EDs where the primary problem was thought to be due to a mental health disorder. This was estimated to be approximately 3.2% of total presentations to public hospital EDs.4 This correlates well with other studies and US figures, which estimate 2–6 % of emergency medicine presentations are primarily due to mental health disorders.1,7,8,9

Two-thirds of these people are between the ages of 15 and 44 years (compared to 42% for the general population presenting to a suburban ED. 29% have anxiety and neurotic disorders, 21% mental and behavioural disorders due to psychoactive substance abuse, 19% mood disorders and 17% schizophrenia or delusional disorders.7

This, of course, is a gross underestimate of the prevalence of mental health disease in the ED as many patients remain undiagnosed, and many have active medical conditions and a mental health diagnosis may be secondary.8

It is estimated that 17.7% of adult Australians admitted to hospital report a mental health issue in the previous 12 months. An estimated 0.4–0.7% of the adult population suffer from a psychotic episode in any one year.5 Mental health issues are highly prevalent and relevant.

Introduction to the mental state examination

The mainstreaming of mental health patients into general EDs has brought problems and anxieties for staff. Staff often feel a lack of confidence because they are dealing with a population of patients unfamiliar to them. They also feel inadequate due to poor assessment skills.9,10

Mental health patients are often seen as ‘low yield’, unrewarding and there is often a negative attitude expressed toward them.9,10 A high proportion have drug and alcohol intoxication. This confounds the evaluation and treatment, lengthens the stay of these patients within the ED and delays their disposition. Mental health patients are sometimes perceived as ‘frequent flyers’ – victims of chronic disease that can never be cured – and can be seen as burdensome and unrewarding.

These negative attitudes have resulted in mental health patients being assigned lower triage categories and longer waits to be seen by staff than mainstream patients. They have a higher chance of leaving before assessment has begun or is complete and the overall increase in length of assessment time has the potential to increase violence in the ED.9,10

Bias and discrimination

It is important for health professionals assessing the mentally ill to be aware of their own potential biases. An interviewer’s past history and personal beliefs can influence a mental state assessment and the interviewer should be aware of this. These beliefs may stem from past personal or professional experience (Table 20.1.1).

ABC of the MSE

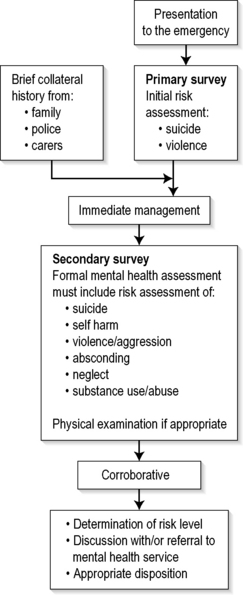

A mental state examination (MSE) is analogous to the management of severe trauma. There is an initial risk assessment looking for immediately life-threatening risks to the patient or staff. The triage nurse and the treating doctor should then obtain a brief collateral history from the emergency services or carers, and initial management is based on this assessment. Regardless of threat, all assessments should balance the safety of both patient and staff with privacy and dignity.9

Assessment should be based on:2

If the situation is relatively controlled, the formal mental health assessment should then take place. Further information is gathered from the community. A provisional assessment and management plan is developed in conjunction with the mental health team, and appropriate disposition is arranged (Fig. 20.1.1).

Triage

The Mental Health Triage Scale (Table 20.1.2) has been developed and modified to be included into the Australian Triage Scale (ATS).3,9,11 It is very broad and asks the triage nurse to make four assessments: risk of suicide/self harm, risk of aggression/harm to others, risk of absconding and whether the patient is intoxicated. From this, the triage nurse determines the ATS and urgency of initial treatment. It is also helpful to determine if the patient is known to a mental health service.

| ATS 2 | Patient is violent, aggressive or suicidal, or is a danger to self or others |

| Requires police escort/restraint | |

| ATS 3 | Very distressed or acutely psychotic |

| Likely to become aggressive | |

| May be a danger to self or others | |

| ATS 4 | Long-standing or semi-urgent mental health problem and/or has supporting agency/escort present |

| ATS 5 | Patient has a long-standing non-acute mental health disorder but has no support agency |

| Many require referral to an appropriate community resource |

Many centres have developed a triage risk assessment proforma. For ease of use, many of these have included ‘tick box’ areas. A compilation of multiple assessment tools used throughout Australia is shown in Tables 20.1.3, 20.1.4 and 20.1.5.1,2,3,5,11,12

Table 20.1.3 Brief screening suicide risk template

| Mental state |  Active disease Active disease |

Depression Depression |

|

Psychosis Psychosis |

|

Hopelessness/despair/guilt/shame Hopelessness/despair/guilt/shame |

|

Anger/agitation Anger/agitation |

|

Impulsivity Impulsivity |

|

| Suicide attempts/thoughts |  Continual/specific thoughts Continual/specific thoughts |

Formulated plan Formulated plan |

|

Intent Intent |

|

Past history of attempt with high lethality Past history of attempt with high lethality |

|

Means Means |

|

Suicide note Suicide note |

|

Risk of being found Risk of being found |

|

Organizing personal affairs Organizing personal affairs |

|

| Substance abuse |  Current misuse Current misuse |

| Supports |  Lack of or hostile relationships Lack of or hostile relationships |

| Loss |  Recent major loss (even perceived): significant relationship, job, housing, financial difficulties, independence Recent major loss (even perceived): significant relationship, job, housing, financial difficulties, independence |

Recent/new diagnosis of major illness or chronic illness Recent/new diagnosis of major illness or chronic illness |

|

| Patients then stratified into high, medium or low risk | |

Table 20.1.4 Aggression risk tool

Alert on chart Alert on chart |

Previous history of violence/threatening behaviour: verbal or physical Previous history of violence/threatening behaviour: verbal or physical |

Aggressive behaviour/thoughts Aggressive behaviour/thoughts |

Homicidal ideation Homicidal ideation |

Use of weapons previously Use of weapons previously |

Access to weapons Access to weapons |

Intoxicated Intoxicated |

Middle aged male Middle aged male |

| Patient then stratified into high, medium or low risk |

Table 20.1.5 Risk of absconding

| Mode of arrival |

Police Police |

Handcuffed Handcuffed |

Family/carer coercion Family/carer coercion |

Voluntary Voluntary |

Past history of absconding behaviour Past history of absconding behaviour |

Alert on chart Alert on chart |

Verbalising intent to leave Verbalising intent to leave |

Lack of insight into illness Lack of insight into illness |

Poor/non-compliance with medication Poor/non-compliance with medication |

| Patients then stratified into high, medium or low risk |

It is recommended that any patient who scores ‘high risk’ in any one area or ‘medium risk’ in two areas is treated as a ‘high risk’ patient. Ensuing management of ‘high risk’ patients depends on: local protocols, levels and presence of security, police intervention, restraint and sedation guidelines and guidelines for the urgent assessment by ED and/or by mental health services.

Aims of mental health assessment

The aims of the formal mental health assessment are to determine the following:

Only if all of the above are answered, can management and appropriate disposition be considered.

The formal psychiatric interview

Introduction

The interviewer should sit at the same level as the patient and impart empathy. The voice should be quiet and calming. The interviewer should use non-judgemental language and open-ended questions.3,13 It is important that the interviewer also feels safe and secure. If any risk is felt, the interviewer should have security or police present in the room or just outside. Depending on state legislation and hospital policy, the interviewer may request to have the patient searched. The interviewer should also note the nearest duress alarm and/or choose to wear a personal alarm. The interviewer should sit within easy access of an exit and should never be boxed into a corner. If an interviewer begins to feel uncomfortable, there is always the option of leaving and returning to complete the assessment at a later stage. All threats, attempts and gestures suggestive of violence should be treated seriously.

First part of the interview: direct questioning

Basic demographic information

These questions assist by building a profile of lifestyle, relationships and thought processes. Likelihood of success or failure of particular treatment modalities may be assisted by knowledge of previous hospital admissions (both general hospital and mental health) (Table 20.1.6).

| Age/date of birth |

| Address |

| Accommodation history |

| Other persons in household |

| Occupation |

| Occupational history |

| Social resources: |

Insight and judgement

Insight is the degree of understanding of what is happening and why. This may be:

Second part of interview: observation

Appearance, attitude and behaviour

This determines the patient’s ability to self care. Table 20.1.8 lists features that may require particular attention. Attitude is important as it may indicate whether a patient is compliant with management and treatment. Abnormal posturing or repetitive behaviours should be noted. These may indicate increasing thought disturbance. With increasing aggression and agitation, there may be motor restlessness, pacing and hand wringing. Tension may escalate rapidly, and steps should be taken early to diffuse the situation.

| General: |

Thought disorder

This is speech that does not reach its goal, is not fluent and is interrupted often with many pauses and/or changes in direction. A list with explanations is given in Table 20.1.9.

| Circumstantiality | Delays in reaching goals by long-winded explanations, but eventually gets there |

| Distractible speech | Changes topic according to what is happening around the patient |

| Loosening of associations | Logical thought progression does not occur and ideas shift from one subject to another with little or no association between them |

| Flight of ideas | Fragmented, rapid thoughts that the patient cannot express fully as they are occurring at such a rapid rate |

| Tangentiality | Responses that superficially appear appropriate, but which are completely irrelevant or oblique |

| Clanging | Speech where words are chosen because they rhyme and do not make sense |

| Neologisms | Creation of new words with no meaning except to the patient |

| Thought blocking | Interruption to thought process where thoughts are absent for a few seconds and are unable to be retrieved |

Cognitive assessment and physical examination

Approximately 20% of mental health patients have a concurrent active medical disorder requiring treatment and possibly contributing to the acute behavioural disturbance.8 Investigations depend on physical findings but may include creatine kinase, urine drug screen, electroencephalogram, computerized tomography and lumbar puncture. Only after this can an emergency medicine practitioner plan the most appropriate management for the patient.

Conclusion

Only then will the mental health professional be able to administer mental health first aid,5 the principles of which are:

1 Crowe M, Carlyle D. Deconstructing risk assessment and management in mental health nursing. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2003;43(1):19-27.

2 Risk McSherryB. Assessment by Mental Health Professionals and the Prevention of Future Violent Behaviour. Australian Government. Australian Institute of Criminology, 2004. July

3 NSW Department of Health. Framework for suicide risk assessment and management. Emergency Department, 2004. http://www.health.nsw.gov.au. Online. Available

4 The Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Mental health services in Australia 2004–5. (Mental Health Series No 9). Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2007.

5 Kitchener B, Jorm A. Mental health first aid manual. Melbourne: Orygen Research Centre, 2002.

6 Clinical Practice Guidelines Team for Depression, Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists. Australian and New Zealand clinical practices. Practice guidelines for the treatment of depression. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 2004;38:389-407.

7 Larkin GL, Classen CA, et al. Trends in US Emergency Departments. Visits for mental health conditions, 1992–2001. Psychiatric Services June. 2005;56(6):671-677.

8 ACEP Clinical Policies Subcommittee. Clinical policy: critical issues in the diagnosis and management of the adult psychiatric patient in the emergency department. Annals of Emergency Medicine. 2006;47(1):79-99.

9 Smart D, Pollard C, Walpole B. Mental health triage in emergency medicine. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 1999;33:57-66.

10 Happell B, Summers M, Pinikahana J. Measuring the effectiveness of the national Mental Health Triage Scale in an emergency department. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing. 2003;12:288-292.

11 Department of Health and Ageing. Emergency triage education kit. Australian Government. 2007:37-48.

12 Department of Human Services, Victorian Emergency Department. Mental health triage tool. Online. http://www.health.vic.gov.au/emergency/mhtriagetool.pdf. Available

13 Meyers J, Stein S. The psychiatric interview in the emergency department. Emergency Medicine Clinics of North America. 2000:173-183.

20.2 Distinguishing medical from psychiatric causes of mental disorder presentations

Introduction

The concept of differentiating an organic from a psychiatric basis for a mental disorder is becoming increasingly blurred as research shows the biological and genetic basis of many traditional psychiatric illnesses. The accepted terminology for classification of mental disorder is also rapidly changing. One accepted Western standard is the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition (DSM-IV).1 To emphasize the biological basis of many traditional psychiatric illnesses, DSM-IV no longer uses the term ‘organic mental disorder’. Despite this change, current clinical management and disposition still revolve around the traditional distinction of organic (medical) from psychiatric problems.

In practice emergency physicians need a simple classification defining the principal diagnosis of the presenting mental disorder consistent with current DSM-IV terminology. This should assist diagnostic, management and disposition accuracy. Table 20.2.1 is such a suggested classification. A more simplistic grouping into psychiatric, medical, substance-related or anti-social behaviour may even suffice. Correct assignment by the emergency physician to the appropriate classification, and hence appropriate disposition, reduces medical costs and morbidity.2

Table 20.2.1 A simple classification of principal diagnosis of mental disorder for emergency physicians

| DSM-IV terminology | Broad traditional clinical grouping | Likely principal management and disposition |

|---|---|---|

| Axis 1 | ||

| Clinical disorder due to a general medical disorder | Organic | Medical |

| Delirium, dementia and amnestic and other cognitive disorders | Organic | Medical |

| Substance-related disorder – intoxication or withdrawal disorder | Organic | Medical |

| Substance-related disorder – substance induced persistent disorder | Organic | Psychiatric |

| Clinical disorder (not identified to above or axis II principal diagnosis) | Psychiatric | Psychiatric |

General approach

Patients with abnormal behaviour labelled as psychiatric after routine medical and psychiatric assessment frequently have a final diagnosis of a medical cause or precipitant for the mental disorder. The incidence of missed medical diagnosis ranges between 8 and 46%.2–4 A prospective study of ED patients in the USA showed a medical diagnosis in 63% of patients with first psychiatric presentations.5 Deciding whether a particular presentation of mental disorder is medical or psychiatric is often difficult, as there are very few absolutes that distinguish medical from psychiatric illness. Careful collection and weighing of appropriate information commonly leads to an accurate differential diagnosis.

Some diagnoses and dispositions can be determined quickly after a medical and psychiatric history, with the addition of a mental state and full physical examination. This may sometimes take place without expensive diagnostic procedures.6 Other presentations are difficult and require extensive and intensive evaluation, repeat evaluation, observation in hospital and significant investigations before the diagnosis is clear.

Many initial assessments in EDs are difficult and inaccurate owing to the presence of intoxicating substances or difficult patient factors. The latter may include poor communication ability, poor cooperation with examination, antisocial behaviour, intentional obscuring of information or denial of problems. Intoxicated patients may have other complex and distracting issues, such as threats of violence or self-harm, possible head injury, possible unknown substance overdose, and poor cooperation with necessary history, examination and investigations. A non-judgemental approach with prudent intervention based on known or likely risks, close monitoring in a safe environment, and repeated reassessment of physical and mental state over time are necessary to obtain an accurate diagnosis and optimal outcome.

Studies on medical clearance by ED staff, primary-care physicians and psychiatrists have repeatedly shown a poor ability to discover medical conditions. This failure is commonly due to one or more of the following factors: inadequate history, failure to seek alternative information from relatives, carers and old records, poor attention to physical examination, including vital signs, absence of a reasonable mental state examination, uncritical acceptance of medical clearance by receiving psychiatric staff and failure to re-evaluate over time.7 A recent study noted that medical conditions were most easily identified in the ED by the triage nurse or medical officer asking whether any medical conditions existed in addition to the patient’s psychiatric complaints.8

Evaluation requires a thorough approach and a commitment of time and effort. Special skills are required for medical clearance and psychiatric interview. A coordinated and focused medical and psychiatric assessment has the highest yield of correct diagnoses.2 Proformas may improve compliance and documentation of important details.

Triage

Triage is vital, as many patients presenting with apparent psychiatric problems have medical conditions. The patient previously labelled psychiatric must be carefully triaged to avoid any new medical problems being overlooked. Psychiatric patients have been found to express their physical illnesses in different ways from those without mental illness. They may be suffering from severe or life-threatening illness, but fail to communicate this to their medical carers. Correct identification at the point of entry by nursing staff facilitates correct management and reduces morbidity and mortality.9 Many patients with psychiatric illness are also a significant risk to themselves or others, and require urgent intervention. Questions regarding safety should always be raised10 (Table 20.2.2).

| Is the patient a danger to him or herself? |

| Is the patient at risk of leaving before assessment? |

| Is the patient a danger to others? |

| Is the area safe? |

Nursing staff should use a triage checklist to identify likely organic presentations (Table 20.2.3). These are indications for urgent medical assessment. If these are absent and a psychiatric diagnosis is likely, then an appropriate urgency rating by Australasian Triage Scale for psychiatric presentations should be applied. This triage categorization for psychiatric presentations has been developed and verified, and allows reasonable waiting time standards for urgency to be applied (Table 20.2.4).11

Table 20.2.3 High-yield indicators of organic illness

Table 20.2.4 Guidelines for Australasian Triage Scale coding for psychiatric presentations11

| Emergency: Category 2 |

| Patient is violent, aggressive or suicidal, or is a danger to self or others, or requires police escort. |

| Urgent: Category 3 |

| Very distressed or acutely psychotic, likely to become aggressive, may be a danger to self or others. |

| Experiencing a situation crisis. |

| Semiurgent: Category 4 |

| Long-standing or semi-urgent mental health disorder and/or has a supporting agency/escort present (e.g. community psychiatric nurse*) |

| Non-urgent: Category 5 |

| Long-standing or non-acute mental disorder or problem, but the patient has no supportive agency or escort. Many require a referral to an appropriate community resource. |

* It is considered advantageous to ‘up triage’ mental health patients with carers present because carers’ assistance facilitates more rapid assessment.

Triage should consider patient privacy issues if the history obtained is to be accurate. Collateral information from the carers with the patient should always be diligently obtained, carefully considered and documented. Integration of all this information should allow the patient to be placed in an appropriate and safe environment where continuing visual and nursing observations can occur while further assessment is awaited. An emerging trend is to use nursing triage to immediately refer likely psychiatric presentations to mental health clinicians without formal ‘medical clearance’. This method appears effective and efficient for both patient and clinicians. Most triage referral systems have built-in medical safety nets and have been operating now for some years without obvious increase in adverse outcomes. They are yet to be validated by scientific studies.

History

HIV is an increasingly important area as HIV-related illness becomes the new great mimic of modern psychiatry and medicine. Practices likely to have put the patient at risk should be explored. These may have been in the distant past. Known positive HIV status always warrants assessment for an organic cause of any new behavioural disturbance. Clinically, these problems often initially present with symptoms of mild anxiety or depression. Many treatable medical causes are only evident after significant investigations.12

Examination

Vital signs

Abnormal vital signs are frequently the only abnormality found on examination of patients with serious underlying medical disease. They must always be acknowledged and explained. Pulse oximetry should be included to rapidly exclude hypoxia. A bedside blood sugar level should be routine for patients with abnormal behaviour.

Mental state examination

This is an account of objective findings of mental state signs made at the time of interview. It is the psychiatric equivalent of the medical examination, and specifically details the current status.13 Observations made by other staff in the department, such as hallucinations, may be very significant and can be included with the source identified. Careful consideration of the mental status frequently clearly distinguishes medical from psychiatric illness, and guides further investigation and management. For example, the presence of delirium or other significant cognitive defects make an organic illness almost certain. Delirium can be very subtle. Sometimes, owing to the fluctuating nature, the patient may appear normal on a single interview. Other less obvious features, such as lability of mood, variability of motor activity or lapses in patient concentration making the interview more difficult, can be the only clues and can be easily overlooked. The importance of formulation using collateral history and repeated mental state examination is stressed. Documentation is important so that mental status changes with time during assessment can be appreciated.

Examination tools

Cognitive defects may be rapidly and reliably identified in the ED during mental status examination by the use of Folstein’s Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE)14 (Table 20.2.5). A score of less than 20 suggests an organic aetiology. A fall of two or more points on serial MMSE is highly suggestive of delirium.15 Elderly patients with delirium or cognitive defects are frequently not recognized by emergency physicians.16 These patients are at high risk of morbidity and mortality.17 Simple assessment methods such as the confusion assessment method (CAM) are rapid, reliable methods of identifying delirium in older patients, suitable for ED use.18 Use of such simple methods should be encouraged to reduce inappropriate disposition. The tests above are suitable screening tools for EDs but are not intended to replace formal neuropsychological assessment. Proformas of medical history, mental state examination and physical examination may improve thoroughness of assessment and documentation.

| Date of assessment Cognition | Points |

|---|---|

| Orientation | |

| 1. What is the date? | 1 |

| What is the day? | 1 |

| What is the month? | 1 |

| What is the year? | 1 |

| What is the season? | 1 |

| 2. What is the name of this building? | 1 |

| What floor of the building are we on? | 1 |

| What city are we in? | 1 |

| What state are we in? | 1 |

| What country are we in? | 1 |

| Registration | ||

| 3. I am going to name three objects. After I have said them I want you to repeat them. Remember what they are because I am going to ask you to name them in a few minutes. | ||

| APPLE TABLE PENNY | ||

| APPLE | 1 | |

| TABLE | 1 | |

| PENNY | 1 | |

| Code first attempt and then repeat the answers until the patient learns all three. | ||

| Attention and calculation | ||

| 4. Can you subtract 7 from 100, and then subtract 7 from the answer you get and keep subtracting until I tell you to stop? | 93 | 1 |

| 86 | 1 | |

| 79 | 1 | |

| 72 | 1 | |

| 65 | 1 | |

| OR | ||

| 5. I am going to spell a word forwards and I want you to spell it backwards. The word is ‘WORLD’. | ||

| Now you spell it backwards. Repeat if necessary. | ||

| D | 1 | |

| L | 1 | |

| R | 1 | |

| O | 1 | |

| W | 1 | |

| Recall | ||

| 6. Now what are the three objects I asked you to remember? | ||

| APPLE | 1 | |

| TABLE | 1 | |

| PENNY | 1 | |

| Language | ||

| 7. Show wristwatch | ||

| What is it called? | ||

| Interviewer: Show pencil | ||

| What is it called? | 2 | |

| 8. I’d like you to repeat a phrase after me. | ||

| ‘NO IFS ANDS OR BUTS’ | 1 | |

| 9. Read the words on the bottom of this table and do what it says. | 1 | |

| 10. Interviewer: Read the full statement below before handing the respondent a piece of paper. ‘Do not repeat or coach.’ | ||

| I am going to give you a piece of paper. | ||

| What I want you to do is take the paper in your right hand, fold it in half and put the paper on your lap. | Takes with right hand | 1 |

| Folds in half | 1 | |

| Puts on lap | 1 | |

| 11. Write a complete sentence on this piece of paper. Sentence should have subject, verb and make sense. Spelling and grammatical errors are okay. | 1 | |

| 12. Here is a drawing. Please copy the drawing on the same paper. Hand drawing to respondent. Correct if two convex five-sided figures and intersection makes a four-sided figure. | 1 | |

| TOTAL SCORE……………………………………………………………………………………………………… | ||

| (Score best of question 4 or 5 to give a total out of 30) | ||

| A score of 20 or less indicates cognitive impairment. | ||

| CLOSE YOUR EYES | ||

Investigations

Investigations should always be guided by clinical findings and must be tailored to each individual presentation. First presentations and suspicion of a medical cause that needs to be confirmed or excluded are the major indications. Baseline blood tests, such as full blood profile, blood sugar level, electrolytes, liver function tests, calcium and thyroid function tests, may at times detect clinically unsuspected problems. Examination and culture of urine and cerebrospinal fluid should be undertaken if occult infection is considered a possible cause. A urine drug screen may on occasion be the only way to confirm clinical suspicions of drug-related illness. Time delays for results, low specificity from cross-reactivity and uncertainty caused by drugs with long half-lives limit their usefulness. Newer drug-screening stat tests at the bedside may improve their usefulness in the ED. Mandatory brain computerized tomography (CT) is not indicated,19–21 but the threshold for imaging in first presentations of altered mental state without obvious cause should be low. HIV and syphilis testing should be done on all patients with significant risk profile. Newer modalities such as magnetic resonance imaging, magnetic resonance spectroscopy, positron emission tomography and single-photon emission CT continue as research tools but may have a role in the future. Electroencephalogram examination is rarely a current ED test for psychiatric patients.

Diagnostic formulation

Emergency physicians should suspect organic disease until proved otherwise. In particular, reversible medical causes of abnormal mental state should be sought. Proformas improve documentation and summation.22 Consideration of the factors in Table 20.2.6 may help to determine doubtful cases. There are few absolutes that distinguish organic from psychiatric patients. Use of the five-axis DSM-IV system improves the ability to look at the patient’s presentation in the context of total functioning.1 It also allows emergency physicians to communicate with psychiatric peers in the recognized language.

Table 20.2.6 Factors influencing the likelihood of medical or psychiatric illness as the principal diagnosis

| Organic | Psychiatric |

|---|---|

| Abnormal vital signs | Family history of psychiatry disorder |

| Age >40 with first psychosis | Past psychiatric illness |

| Delirium | Fully orientated |

| Conscious level fluctuates | Clear sensorium |

| Inability to attend | |

| Memory impaired | |

| Impaired cognitive abilities | Intact cognition |

| Neurological signs, e.g. dysarthria | |

| Abnormal physical signs | |

| Abrupt onset | Slow onset |

| Dramatic change in general status (hours to days) | Premorbid slow deterioration in employment/family/socially |

| Recent medical problem | Recent significant life event |

| Medication, drugs/alcohol/withdrawal | Non-compliance psychiatric medication |

| Marked new personality changes | |

FH, family history.

A common expectation of emergency physicians for patients referred to psychiatrists is to document that the patient is ‘medically cleared’. The assessment is known to be imprecise and difficult.2–5,8–10,22 Better documentation is to state that the ED assessment has revealed no evidence of an emergent medical problem.

Conclusion

A thorough medical history, psychiatric history, collateral history, physical examination, mental state examination and judicious specific investigation will identify most patients likely to have an underlying physical cause for a mental disorder presentation. Omission of any of these steps may lead to missed medical diagnosis and incorrect disposition.

Controversies and future directions

1 American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 4th edn. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association, 1994.

2 Hoffman RS. Diagnostic errors in the evaluation of behavioural disorders. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1982;248:964-967.

3 Koranyi EK. Morbidity and rate of undiagnosed physical illnesses in a psychiatric clinic population. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1979;36:414-419.

4 Hall RC, Popkin MK, Devaul RA, et al. Physical illness presenting as psychiatric disease. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1978;35:1315-1320.

5 Henneman PL, Mendoza R, Lewis RJ. Prospective evaluation of emergency department medical clearance. Annals of Emergency Medicine. 1994;24:672-677.

6 Allen MH, Faumann MA, Morin FX. Emergency psychiatric evaluation of ‘organic’ mental disorders. New Directions for Mental Health Services. 1995;67:45-55.

7 Tintinalli JE, Peacock FW, Wright MA. Emergency medical evaluation of psychiatric patients. Annals of Emergency Medicine. 1994;23:859-862.

8 Olshaker JS, Browne B, Jerrard DA, et al. Medical clearance and screening of psychiatric patients in the emergency department. Academic Emergency Medicine. 1997;4:124-128.

9 Ferrera PC, Chan L. Initial management of the patient with altered mental status. American Family Physician. 1997;55:1773-1780.

10 Pollard C. Psychiatry reference book – nursing staff. Hobart: Department of Emergency Medicine Royal Hobart Hospital, 1994.

11 Smart D, Pollard C, Walpole B. Mental health triage in emergency medicine. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 1999;33:57-66.

12 Sternberg DE. Testing for physical illness in psychiatric patients. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 1986;47(suppl 1):3-9.

13 Dakis J, Singh B. Making sense of the psychiatric patient. Foundations of clinical psychiatry. Melbourne: Melbourne University Press, 1994;79.

14 Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. ‘Mini Mental State’: A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 1975;12:189-198.

15 O’Keefe ST, Mulkerrin EC, Nayeem K, et al. Use of serial Mini-Mental State Examinations to diagnose and monitor delirium in elderly hospital patients. Journal of American Geriatrics Society. 2005;53(5):867-870.

16 Hustey FM, Meldon SW. The prevalence and documentation of impaired mental status in elderly emergency department patients. Annals of Emergency Medicine. 2002;39(3):248-253.

17 Trzepacz P, McIntyre SC, Charles, et al. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with delirium. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1999;156(5 suppl):1-20.

18 Inouye SK, van Dyck CH, Alessi CA, et al. Clarifying confusion. The confusion assessment method. A new method for detection of delirium. Annals of Internal Medicine. 1990;113:941-948.

19 Weinberger DR. Brain disease and psychiatric illness: when should a psychiatrist order a CAT scan? American Journal of Psychiatry. 1984;41:1521-1527.

20 Sata LS. Diagnosing organic psychosis. Maryland State Medical Journal. 1970;19(2):61-64.

21 Ananth J, Gamal R, Miller M, et al. Is routine CT head scan justified for psychiatric patients? A prospective study. Journal of Psychiatry and Neuroscience. 1993;18:69-73.

22 Riba M, Mahlon H. Medical clearance: fact or fiction in the hospital emergency room. Psychosomatics. 1990;31:400-404.

20.3 Deliberate self-harm/suicide

Introduction

Suicide is a deliberate act of intentional self-inflicted death. It is the most extreme expression of suicidality, which also comprises suicidal thoughts, threats, planning and attempted suicide through deliberate self-harm (DSH). Although suicide is uncommon, 10% of people who commit suicide are seen in an emergency department (ED) in the month prior to death, with a substantial proportion not having psychosocial assessment, thus providing an opportunity for intervention.1,2 The major ED impact, however, is in the assessment of large numbers of potentially suicidal patients, accurate risk stratification, and initial control and management of these patients.

DSH is a maladaptive response to stress and a manifestation of suicidality, but can also occur without any intent to die with other psychiatric and personality disorders.3 Deliberate self-harm is a common ED presentation (approximately 0.5% of all ED visits4) and the goals of management include treatment of the physical sequelae, assessment of risk of non-fatal or fatal repetition, and diagnosing and commencing treatment of potentially reversible psycho-social causes.5

Incidence

In Australia there were approx 2100 deaths per year from suicide in 2004 and 2005, with age-standardized rates of approximately 16.4 per 100 000 in males and 4.3 in females.6 Suicide accounts for 1.6% of deaths in Australia and is in the top 10 causes of death despite a reduction of approximately 30% in suicide rates from 1997 to 2004.7 Suicide rates are similar in the UK, New Zealand, Canada and the USA, suicide accounting for 1–2% of all deaths in these countries.6,8–11 The national rates of suicide vary: Japan, Scandinavian and Eastern European countries have population suicide rates as high as 25:100 000, whereas some southern European and Middle Eastern countries have rates less than 5:100 000.11,12

Hospital presentations for DSH are at least 10 times higher than suicide rates.6,9 In the 1997 Australian National Survey of Mental Health, 0.3% of males and 0.4% of females reported they had made a suicide attempt in the previous 12 months. Most of these are not reported or are reported as accidents. Hence unrecognized DSH is at least as frequent as that recognized. The same survey reported 2.7% of males and 4.5% of females experienced suicidal thoughts within 12 months.13 This rate may be as high as 25% in certain populations and age groups.14,15

Aetiology

The most frequent methods of suicide in Australia are hanging (approximately 50% of male and 40% of female suicide deaths) and deliberate self-poisoning (approximately 30% of males and 40% of females). Firearms accounted for 7% of suicide deaths in Australia in 2005, a rate which has declined from 20% a decade prior, possibly due to firearm restriction legislation.6 Proportions due to each method vary according to region, residence, age and sex.1,16 In the USA, firearms accounted for 57% of male and 32% of female suicide deaths. In many developing countries, organophosphate or antimalarial poisoning is the most common method of suicide.17,18

Patient characteristics

Demographic factors

Age

Suicide and DSH are rare in children under 12 years of age. Australian data suggest similar rates of suicide from the age of 20 to 50, with a peak at 30–34 years in males and 35–39 in females.6,19 There is another peak in the elderly, with suicide rates increasing with age from 65 years. This bimodal distribution is also evident from USA and New Zealand data, with males aged over 80 years having the highest age specific rates of suicide.

The incidence of DSH increases throughout puberty, reaching a peak at 15–24 years of age and decreasing thereafter. The ratio of rates of DSH to suicide decreases markedly with age. DSH is uncommon in the elderly, who have a high ratio of successful to unsuccessful attempts.20

Social and cultural factors

Recent data in Australian Aboriginal people report substantially higher suicide rates that commence at a lower age than in the non-Aboriginal population.6,19 This has also been reported in New Zealand Maoris, Native Americans and Inuit in Canada.9,10,21 Suicide rates of migrants initially reflect rates in the country of origin and converge toward the Australian rate over time.

Some higher social status groups such as doctors, dentists, musicians, lawyers and law-enforcement officers are more prone to suicide.22 Most adults (75%) with DSH have relationship problems with their partners, and teenagers with their parents. A major argument or separation often precedes the act on a background of ongoing social difficulties and substance use.

Psychiatric factors

There is a pre-existing psychiatric disorder in 90–100% of cases of suicide, of which depression accounts for 66–80%, but this rate may be based on retrospective psychological analysis.23,24 The rate of suicide among psychiatric inpatients is 3–12 times higher than in the general population and involves more violent methods, such as jumping from buildings, hanging or jumping in front of vehicles. One-third of these episodes occur after self-discharge from hospital, with another third occurring during approved leave. The high-risk time is the first week of admission and during the first 3 months after discharge.25 Psychiatric disorders are present in up to 60% of patients who commit DSH, but may be transient and secondary to acute psycho-social difficulties.

Affective disorders

The psychiatric diagnosis that carries the greatest risk of suicide is mood disorder, particularly major depression if associated with borderline personality disorder, anxiety or agitation.26 Fifteen per cent of these high-risk patients commit suicide over a lifetime. Depression correlates well with the occurrence of suicidal desire and ideation, but may not be as strong a predictor of planning and preparation (intense thoughts, plans, courage and capability) and, therefore, suicide completion.24 Hopelessness is the most important factor associated with suicide completion and may be of greater importance than suicidal ideation or depression itself.24 Depressed patients should, therefore, have their attitudes towards the future carefully assessed.

Substance abuse

Fifteen per cent of alcohol-dependent persons eventually commit suicide. The majority of these are also depressed. The risk is higher if associated with social isolation, poor physical health, unemployment and previous suicidal behaviour. The increased risk may be more pronounced in males aged below 35 years.27 There is an increased risk of suicide in patients who use recreational drugs. Young male heroin addicts may have 20 times the risk of the general population. Chronic alcohol dependence is uncommon in DSH, but alcohol intoxication is involved in 50–90% of suicide attempts.

Personality disorders

Patients with antisocial and borderline personality disorders are at high risk of DSH and suicide, especially if associated with labile mood, impulsivity, alienation from peers and associated substance abuse. This may be due to precipitation of undesirable life events, predisposition to psychiatric and substance-abuse disorders, and social isolation. Adjustment disorders are associated with 25% of adolescent suicide.23

Assessment

A person who expresses suicidal ideation or commits an act of DSH is sending a distress signal that emergency physicians must recognize and assess for further risk. Suicidality should also be assessed in patients with symptoms or signs of depression, unusual behavioural changes, substance abuse, psychiatric disorders, complainants of sexual violence,28 and those who present with injuries of questionable or inconsistent mechanism, such as self-inflicted lacerations and gunshot wounds or motor vehicle accidents involving one victim.

Triage

In a patient who has attempted DSH, initial management involves resuscitation, treatment of immediate life threats and preventing complications. The patient should be triaged according to the physical problem as well as current suicidality, aggressiveness and mental state. The mental health triage scale can be used for this purpose.29 A triage score of 2 or 3 should be applied if patients are violent to themselves or others, actively suicidal, psychotic or distressed, or at risk of leaving before full assessment. Constant observation is required at this point and nursing staff, orderlies, security or police may be needed.

Suicide risk assessment

Initially, this needs to be done in the ED so as to determine patient disposition, but full psychiatric assessment may need to wait until drug effects wear off. Other sources of information need to be accessed since patient history can be unreliable or incomplete. Friends, family, local doctor, ambulance officers, helping agencies already involved and previous presentations documented in the medical record can all add useful information in order to complete an assessment. A therapeutic relationship should be formed and the clinician should be non-judgemental, non-threatening and clearly willing to help. A negative attitude is common among emergency personnel, especially with repeat attenders. This may intensify the patient’s already low self-esteem, increasing future suicide potential and making a therapeutic relationship difficult to establish.30 When managing a patient who may be suicidal, the suicidal ideation should be discussed openly. This does not increase the likelihood of attempted suicide and may make the patient realize there are other options.

Assessment of suicide risk involves assessing background demographic, psychiatric, medical and social factors, as well as the current circumstances and suicidal behaviour itself, as outlined in Table 20.3.1. There are epidemiological differences between people who attempt suicide and those who complete suicide. Although the groups are different, there is an important overlap. The more an individual’s characteristics resemble the profile of a suicide completer, the higher the risk of future suicide or suicide attempts. Despite this, in long-term follow-up studies very few of these factors have been shown to be good independent predictors of suicide following DSH. The most consistent factors are psychiatric illness, personality disorder, substance abuse, multiple previous attempts, and current suicidality and hopelessness. Guidelines are available to assist in suicide-risk stratification and describe characteristics associated with suicide-risk levels and the appropriate further assessment and disposition for each group.31

| Variable | High risk | Low risk |

|---|---|---|

| Background factors | ||

| Gender | Male | Female |

| Marital status | Separated, divorced, widowed | Married |

| Employment | Unemployed or retired | Employed |

| Medical factors | Chronic illness, chronic pain, epilepsy | Good health |

| Psychiatric factors | Depression, bipolar, schizophrenia, panic disorder, previous psychiatric inpatient, substance abuse | No psychiatric history, normally robust personality |

| Social background | Unresponsive family, socially isolated or chaotic, indigenous background | Supportive family, socially stable and integrated |

| Current factors | ||

| Suicidal ideation | Frequent, prolonged, pervasive | Infrequent, transient |

| Attempts | Multiple | First attempt |

| Lethality | Violent, lethal and available method, aware of medical dangerousness | Low lethality, poor availability |

| Planning | Planned, active preparation, extensive premeditation | Impulsive, no realistic plan, telling others prior to act |

| Rescue | Act performed in isolation, event timed to avoid intervention, precautions taken to avoid discovery | Rescue inevitable, obtained help afterwards |

| Final acts | Wills, insurance, giving away property | |

| Coping skills | Unwilling to seek help, feels unable to cope with present difficulties | Can easily turn to others for help, can plan to overcome present difficulties, willing to become involved in aftercare |

| Current ideation | Admitting act was intended to cause death, no remorse, continued wish to die, hopelessness or helplessness | Primary wish to change, pleased to recover, suicidal ideation resolved by act, optimism |

| Precipitant | Similar circumstances can recur, acute precipitant not resolved | Stressful but transient life event, acute precipitant addressed |

Use of scales

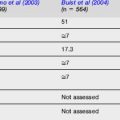

Many screens have been devised to identify high-risk groups within those presenting with DSH. PATHOS,32 the Suicidal Intent Scale,33 the Sad Persons Scale34 and other scoring systems have been devised to complement medical assessment of suicide risk. The modified Sad Persons Scale (Table 20.3.2) incorporates some high-risk characteristics to predict suicide risk in patients with suicidal ideation or behaviour. However, many of these scales use outdated risk factors and patient populations unrepresentative of EDs. Scales need to be sensitive, but this misclassifies a large number of individuals as potentially suicidal. These deficiencies need to be considered when applying suicide risk scales in the ED and these scales should not be used as an absolute assessment of suicide risk or of the need for psychiatric admission.35,36 The problems associated with suicide-risk assessment are summarized in Table 20.3.3.

| Variable | Score |

|---|---|

| Gender: male | 1 |

| Age: <19 or >45 years | 1 |

| Depression: hopelessness, despair, especially if associated with physiological shift symptoms | 2 |

| Psychiatric care: previous DSH, psychiatric care or severe personality disorder | 1 |

| Excessive drug use | 1 |

| Rational thinking loss: severe depression with psychotic features, organic brain syndrome, delusions | 2 |

| Single, separated, divorced, widowed | 1 |

| Organized attempt: planned, premeditated, lethal and available method | 2 |

| No life supports: social isolation, homeless, unemployed | 1 |

| States future intent: continued suicidal ideation | 2 |

Table 20.3.3 Problems in assessing suicide risk

| Suicide is rare, even in high-risk groups, so it cannot be predicted without a high rate of false-negative or false-positive errors |

| Suicidality presents in heterogeneous ways that may not be recognized |

| Suicidality is transient and affected by intoxication, stress and being in hospital |

| The patient may be reluctant, oppositional or manipulative |

| The patient may present in an atypical fashion, especially the elderly with physical complaints |

| Suicide risk factors identify high-risk subgroups but not individuals |

| The demographic factors associated with suicide have changed recently, thus changing the make-up of risk groups |

| Risk factors are based on studies of long-term follow-up and, therefore, long-term risk |

| Subtle changes in mental status and behaviour may be missed if not assessed by the usual doctor |

| Unexplained improvement in psychological status may be the result of increased motivation to die |

| Patients may deny their true intentions due to embarrassment, fear of being stopped in carrying out their own wishes, fear of being institutionalized or fear of the confidentiality of the interview |

| Patients may say life is not worth living or that they feel they would be better off dead, but not necessarily have an increased risk of suicide, unless they have made suicidal plans or attempts, or if they have pervasive hopelessness |

| Correlation between medical danger and suicidal intent is low unless the patient can accurately assess the probable outcome of their attempts if treatment had not been received |

Definitive treatment and disposition

Following necessary medical treatment and suicide-risk stratification, disposition may involve involuntary or voluntary admission to a psychiatric or medical ward, short-term or overnight observation, or discharge with appropriate follow-up. Restraint and involuntary admission may be necessary for the high-risk patient who wishes to self-discharge. Approximately 30% of DSH patients are admitted for psychiatric inpatient care but the factors involved in the decision for psychiatric hospitalization following DSH are not well understood and involve a complex evaluation of risk, potential for treatment and social supports.37

Important elements of management involve neutralizing the precipitating problem, treatment of psychiatric illness and environmental interventions such as family counselling, encouraging a support network, and developing coping and problem-solving skills.38 Open discussion about suicide should be undertaken and a firm stance should be maintained that suicide is an ineffective solution. Alternative, non-suicide solutions should be reinforced. Other factors that should be addressed whilst patients are in hospital include problems with relationships, employment, finances, housing, legal problems, social isolation, alcohol and drug abuse, and bereavement. In this regard, medical social workers or mental health nurses are invaluable.39 For greatest effect, these should be available after hours and on weekends since the majority of DSH presents after hours.40 For repeat attenders or manipulative patients who are often socially isolated, hospitalization should not be a substitute for social services, substance-abuse treatment and legal assistance, although admission may be necessary while appropriate supports are put in place.41

Discharge is appropriate for the low-risk patient who is cooperative, no longer suicidal, not intoxicated, has no underlying psychiatric or substance abuse disorder, and has strong social support with the precipitating problem having resolved due to the act or subsequent assessment and intervention in hospital. Discharged patients should make a commitment to seek help if they reach a crisis point, and the physician should be available to help. This can be part of a commitment to a non-suicidal behavioural plan between the patient and clinician. This contract should be with the clinician who will arrange definitive care. Contracts may delay the patient’s suicidal impulses so that other treatment strategies can be implemented. If discharged, there should be liaison with the patient’s general practitioner and therapist, and follow-up should be confirmed where possible within 1–2 days.

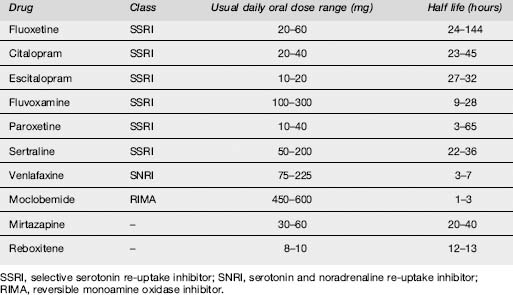

Pharmacotherapy involves the treatment of the underlying psychiatric disorder. Antidepressants decrease the risk of attempting suicide, although the lethality of suicide attempts is increased if tricyclic antidepressants are taken in overdose. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors may have a more selective effect in decreasing suicidal behaviour and are less toxic in overdose. These factors make this class of drugs an attractive choice for depressed patients who are suicidal, but any long-term therapeutic drug should, ideally, be prescribed by the doctor who will provide definitive follow-up.42

Consequences

Risk of suicide

An episode of DSH is probably the best predictor of future suicide. Approximately 1–2% of patients commit suicide during the year following an attempt and in approximately 40% of suicides there is a history of a previous attempt. A systematic review of fatal and non-fatal repetition of self-harm reported a suicide rate of 2% at 1 year and 7% after 9 years.43 In a prospective Finnish 14-year follow-up study, and a UK 18-year follow-up study, the rate of suicide after an episode of DSH was 6.7%.44,45 A 10-year follow-up study in New Zealand documented a suicide rate of 4.6% in patients admitted for DSH.46 Hospitalization and aftercare decrease short-term risk of suicide, but have little impact on long-term risk of suicide. However, this may be due to under-treatment of psychiatric illness.23,47,48

Exposure to suicide in adolescents tends not to cause an increased risk of suicide among friends but may cause an increased incidence of depression anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder.49

Repeated episodes of DSH

DSH usually invokes help from friends, family and the medical profession so that the patient’s social situation and psychological wellbeing tends to improve.50 This cathartic effect is prominent in younger patients but may not occur in patients aged over 60 years.51 The risk of repetition is 12–16% in the following year, with 10% of these occurring in the first week.43,49 This is more likely in females who are unemployed, have cluster B personality traits or have substance-abuse problems.

Patients with DSH who leave the ED prior to a psychosocial assessment may have a higher risk for repeat DSH, probably associated with lack of specialist follow-up and treatment of reversible factors.52,53

Some patients have chronic suicidal ideation and multiple repetitions of DSH. They often suffer from personality disorders, psychotic disorders, chronic medical conditions, alcohol or drug use, a history of childhood sexual abuse54,55 and violent behaviour. They use DSH as a means of fighting off anxiety, hopelessness, loneliness or boredom, or for manipulation of family, friends or health carers. These patients place a heavy burden on hospital resources, are difficult to treat and have a high rate of eventual suicide. Reversible potentiating factors should be addressed where possible.

Increased all cause mortality

A suicide attempt is associated with a severe risk of premature death with the increased mortality rate not entirely due to suicide.56 There is a higher than expected rate of accidents, homicides and death from other medical conditions. This may indicate social disadvantage, a disengagement with the health system, underlying chronic illnesses or lifestyle factors.

Prevention

Comprehensive strategies for prevention of suicide have been or are being developed in Finland, Norway, Sweden, Australia and New Zealand.12 Suicide prevention focuses on psychiatric, social and medical aspects, and usually involves public education, media restrictions on reporting of suicide, school-based programmes with teacher education, training of doctors in detection and treatment of depression and other psychiatric disorders, alcohol and drug-abuse information, enhanced access to the mental health system and supportive counselling after episodes of DSH. Decreasing the availability of lethal methods may involve legislative changes such as more stringent gun control, restricting access to well-known jumping sites or changes to availability or packaging of tablets.57 Overall, studies into the effectiveness of suicide-prevention strategies have shown inconsistent reductions in suicide rates following interventions.58 Approaches to reduce DSH repetition have also shown disappointing results.59 Improved recognition and treatment of mental illness, improved social services, and drug- and alcohol-support services may be of greater benefit than specific suicide-prevention strategies.

Conclusion

1 Salter A, Pielage P. Emergency departments have a role in the prevention of suicide. Emergency Medicine. 2000;12:198-203.

2 Gairin I, House A, Owens D. Attendance at the accident and emergency department in the year before suicide: retrospective study. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2003;183:28-33.

3 Mitchell AJ, Dennis M. Self harm and attempted suicide in adults: 10 practical questions and answers for emergency department staff. Emergency Medicine Journal. 2006;23:251-255.

4 Doshi A, Boudreaux ED, Wand N, et al. National study of US emergency department visits for attempted suicide and self-inflicted injury, 1997–2001. Annals of Emergency Medicine. 2005;46:369-375.

5 Boyce P, Carter G, Penrose-Wall J, et al. Summary Australian and New Zealand clinical practice guideline for the management of adult deliberate self-harm. Australasian Psychiatry. 2003;11:150-155.

6 Australian Bureau of Statistics. 3309.0 Suicides, Australia [Internet homepage]. 2005. http://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/abs@.nsf/Lookup/3309.0Main+Features12005?. [updated 2007, Mar 14; cited 2007, Nov 22]. Available:

7 Australian Bureau of Statistics. 3303.0 Causes of Death, Australia [Internet homepage]. 2005. http://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/abs@.nsf/mf/3303.0/. [updated 2007, Apr 16; cited 2007, Nov 22]. Available:

8 Office for National Statistics. Death rates from suicide [Internet homepage]. 2007. http://www.statistics.gov.uk/statbase/Product.asp?vlnk=13618. [updated 2007, Feb 22; cited 2007, Nov 22]. Available:

9 New Zealand Health Information Service. Suicide facts: provisional 2003 all-ages statistics [Internet homepage]. 2003. http://www.nzhis.govt.nz/stats/suicidefacts2003.pdf. [updated 2006, Feb; cited 2007, Nov 22]. Available:

10 American Association of Suicidology. USA Suicide: 2004 official final data [Internet homepage]. 2004. http://www.suicidology.org/associations/1045/files/2004datapgu1.pdf. [updated 2006, Dec 15; cited 2007, Nov 22]. Available:

11 World Health Organisation. Suicide rates [Internet homepage]. 2003. http://www.who.int/mental_health/prevention/suicide/suiciderates/en/. [updated 2003, May; cited 2007, Nov 22].Available:

12 Taylor SJ, Kingdom D, Jenkins R. How are nations trying to prevent suicide? An analysis of national suicide prevention strategies. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavia. 1997;95:457-463.

13 Pirkis J, Burgess P, Dunt D. Suicidal ideation and suicide attempts among Australian adults. Crisis. 2000;21:16-25.

14 McKelvey RS, Pfaff JJ, Acres JG. The relationship between chief complaints, psychological distress, and suicidal ideation in 15–24 year-old patients presenting to general practitioners. Medical Journal of Australia. 2001;175:550-552.

15 Bertolote JM, Fleischmann A, De Leo D, et al. Suicide attempts, plans, and ideation in culturally diverse sites: the WHO SUPRE–MISS community survey. Psychological Medicine. 2005;35:1457-1465.

16 Dudley MJ, Kelk NJ, Florio TM. Suicide among young Australians, 1964–1993: an interstate comparison of metropolitan and rural trends. Medical Journal of Australia. 1998;169:77-80.

17 Arun M, Menezes RG, Babu YPR. Autopsy study of fatal deliberate self harm. Medicine, Science & the Law. 2007;47:69-73.

18 Eddleston M. Patterns and problems of deliberate self-poisoning in the developing world. Quarterly Journal of Medicine. 2000;93:715-731.

19 Baume P. Suicide in Australia: do we really have a problem? Australian Journal of Education & Developmental Psychology. 1996;13:3-39.

20 Hawton K, Harriss L. Deliberate self-harm in people aged 60 years and over: characteristics and outcome of a 20-year cohort. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2006;21:572-581.

21 Isaacs S, Keogh S, Menard C, et al. Suicide in the Northwest Territories: a descriptive review. Chronic Diseases in Canada. 2000;19. http://www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/publicat/cdic-mcc/19-4/c_e.html. [serial online]. [cited 2007, Nov 22]. Available:

22 Kaplan HI, Sadock BJ, Grebb JA. Kaplan and Sadock’s synopsis of psychiatry, 7th edn, Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1994:803-809.

23 Lönnqvist JK, Henriksson MM, Isometsä ET, et al. Mental disorders and suicide prevention. Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences. 1995;49:S111-S116.

24 Hawton K. Assessment of suicide risk. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1987;150:145-153.

25 Shah AK, Ganesvaran T. Inpatient suicides in an Australian mental hospital. Australia and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 1997;31:291-298.

26 Gilbody S, House A, Owens D. The early repetition of deliberate self harm. Journal of Royal College Physicians London. 1997;31:171-172.

27 Cooper J, Kapur N, Webb R, et al. Suicide after deliberate self-harm: a 4-year cohort study. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2005;162:297-303.

28 Campbell L, Keegan A, Cybulska B. Prevalence of mental health problems and deliberate self-harm in complainants of sexual violence. Journal of Forensic Legal Medicine. 2007;14:75-78.

29 Smart D, Pollard C, Walpole B. Mental health triage in emergency medicine. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 1999;33:57-66.

30 Rund DA, Hutzler JC. Behavioral disorders: emergency assessment and stabilization. In: Tintinalli JE, Kelen GD, Stapczynski JS, editors. Emergency medicine: a comprehensive study guide. 6th edn. New York: American College of Emergency Physicians, McGraw-Hill; 2004:1812-1816.

31 Australasian College for Emergency Medicine and the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists. Guidelines for the management of deliberate self harm in young people. Victoria: ACEM and RANZCP, 2000.

32 Kingsbury S. PATHOS: a screening instrument for adolescent overdose: a research note. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines. 1996;37(5):609-611.

33 Beck AT, Schuyler D, Herman J. Development of suicidal intent scales. In: Beck AT, Resruk HLP, Lettieri DJ, editors. The prediction of suicide. Maryland: Charles Press, 1974.

34 Hockberger RS, Rothstein RJ. Assessment of suicide potential by nonpsychiatrists using the SAD PERSONS score. Journal of Emergency Medicine. 1988;6:99-107.

35 Cochrane-Brink KA, Lofchy JS, Sakinofsky I. Clinical rating scales in suicide risk assessment. General Hospital Psychiatry. 2000;22:445-451.

36 Harriss L, Hawton K. Suicidal intent in deliberate self-harm and the risk of suicide: the predictive power of the Suicide Intent Scale. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2005;86:225-233.

37 Carter GL, Safranko I, Lewin TJ, et al. Psychiatric hospitalisation after deliberate self-poisoning. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 2006;36(2):213-222.

38 Brent DA. The aftercare of adolescents with deliberate self harm. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines. 1997;38(3):277-286.

39 Brakoulis V, Ryan C, Byth K. Patients seen with deliberate self-harm seen by a consultation–liaison service. Australasian Psychiatry. 2006;14:192-197.

40 Bergen H, Hawton K. Variations in time of hospital presentation for deliberate self-harm and their implications for clinical services. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2007;98(3):227-237.

41 Lambert MT, Bonner J. Characteristics and six-month outcome of patients who use suicide threats to seek hospital admission. Psychiatric Services. 1996;47:871-873.

42 Kasper S, Schindler S, Neumeister A. Risk of suicide in depression and its implication for psychopharmacological treatment. International Journal of Psychopharmacology. 1996;11(2):71-79.

43 Owens D, Horrocks J, House A. Fatal and non-fatal repetition of self-harm. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2002;181:193-199.

44 Suokas J, Suominen K, Isometsa E, et al. Long-term risk factors for suicide mortality after attempted suicide – findings of a 14-year follow-up study. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavia. 2001;104:117-121.

45 De Moore GM, Robertson AR. Suicide in the 18 years after deliberate self harm. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1996;169:489-494.

46 Gibb SJ, Beautrais AL, Fergusson DM. Mortality and further suicidal behaviour after an index suicide attempt: a 10-year study. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 2005;39:95-100.

47 Kurz A, Moller HJ. Attempted suicide: efficacy of treatment programs. Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences. 1995;49:S99-S103.

48 McNeil DE, Binder RL. The impact of hospitalization on clinical assessments of suicide risk. Psychiatric Services. 1997;48:204-208.

49 Brent DA, Moritz G, Bridge J. Long-term impact of exposure to suicide: a three-year controlled follow-up. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1996;35:646-653.

50 Sarfati Y, Bouchaud B, Hardy-Bayle M-C. Cathartic effect of suicide attempts not limited to depression: a short-term prospective study after deliberate self-poisoning. Crisis. 2003;24:73-78.

51 Matsuishi K, Kitamura N, Sato M, et al. Change of suicidal ideation induced by suicide attempt. Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences. 2005;59:599-604.

52 Hickey L, Hawton K, Fagg J, et al. Deliberate self-harm patients who leave the accident and emergency department without a psychiatric assessment: a neglected population at risk of suicide. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2001;50:87-93.

53 Kapur N, Cooper J, Hiroeh U. Emergency department management and outcome for self-poisoning: a cohort study. General Hospital Psychiatry. 2004;26:36-41.

54 Soderberg S, Kullgren G, Salander Renberg E. Childhood sexual abuse predicts poor outcome seven years after parasuicide. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2004;39:916-920.

55 Vajda J, Steinbeck K. Factors associated with repeat suicide attempts among adolescents. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 2000;34:437-445.

56 Ostamo A, Lonnqvist J. Excess mortality of suicide attempters. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2001;36:29-35.

57 Cantor CH, Baume PJM. Access to methods of suicide: what impact? Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 1998;2:8-14.

58 Gunnell D, Frankel S. Prevention of suicide: aspirations and evidence. British Medical Journal. 1994;308:1227-1233.

59 Burns J, Dudley M, Hazel P. Clinical management of deliberate self-harm in young people: the need for evidence-based approaches to reduce repetition. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 2005;39:121-128.

20.4 Depression

Introduction

The need to determine the presence and severity of a depressive syndrome is a very frequent task in the emergency department (ED). Assessment of depression is necessary in relation to a variety of patient presentations. The classic ED situation is the overdose, or other attempted suicide or self-harm, where the assessment of depression forms part of further evaluation after the patient has been medically stabilized. It is also becoming more common for patients to present to the ED complaining of depression (often on the advice of family, friends or crisis helplines) without having harmed themselves. Patients with a variety of medical conditions, especially conditions which are chronic or disabling, also often develop a depressive syndrome that can form a major part of the reason behind an ED attendance. Some patients who present to EDs with personal crisis or self-harm may have been identified as suffering from a personality disorder, but nevertheless need assessment for comorbid depression. The evaluation of depressive symptoms is also an important aspect of the assessment of patients seen in the ED with alcohol and drug abuse problems.

In these assessments it is very important to have a clear concept of the syndrome of ‘clinical depression’. This syndrome is called ‘depressive episode’ in The International Classification of Disease – 10th edition1 (ICD-10) and ‘major depression’ in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders – 4th edition2 (DSM-IV). The importance of diagnosing a depressive episode lies principally in determining the presence of a clinical syndrome which is in need of treatment, is likely to respond to treatment and is likely to persist without treatment. The clear delineation of a depressive episode is also an essential basis for differential diagnosis from other medical and psychiatric conditions, and for distinguishing between the clinical syndrome of depression and the day-to-day fluctuations of mood and states of dejection, pessimism, frustration and disappointment which are the lot of all human beings.

The diagnosis of a depressive episode depends on the pervasive presence of a sufficient number of a specific list of symptoms. The list of symptoms contributing to the depressive episode syndrome in ICD-10 is shown in Table 20.4.1. The DSM-IV syndrome of major depression has the same list of symptoms, with the exception of ‘loss of confidence or self-esteem’. An adequate number of these symptoms must be present for at least 2 weeks before the diagnosis of depressive episode can be made. The pervasiveness of the symptoms is defined principally by the specifications that they must be present ‘most of the day’ and for ‘nearly every day’.

Table 20.4.1 Symptoms contributing to the diagnosis of a depressive episode in ICD-101

| 1. Depressed mood, most of the day, nearly every day, largely uninfluenced by circumstances |

| 2. Markedly diminished interest or pleasure in all, or almost all, activities, most of the day, nearly all day |

| 3. Loss of energy or fatigue, nearly every day |

| 4. Loss of confidence or self-esteem |

| 5. Unreasonable feelings of self-reproach, or excessive or inappropriate guilt, nearly every day |

| 6. Recurrent thoughts of death or suicide, or any suicidal behaviour |

| 7. Diminished ability to think or concentrate, or indecisiveness, nearly every day |

| 8. Psychomotor agitation or retardation, nearly every day |

| 9. Insomnia or hypersomnia, nearly every day |

| 10. Change in appetite (decrease or increase with corresponding weight change) |

Epidemiology

Clinical depression, defined as ‘major depression’ or an ICD-10 ‘depressive episode’, is a very common condition. Extensive epidemiological community surveys in many populations around the world have established that the 6-month prevalence rate of major depression is in the range of 2–5% in any population.3 The epidemiological research has also shown that only a minority of persons with current depressive syndromes are receiving active treatment.3

The age onset of the first depressive episode is typically in the third decade, but can be at any age. The male to female ratio is 1:2. A person who has had one episode of clinical depression has an 80% chance of recurrence, and patients with recurrent depression have an average of four episodes in their lifetime.4

Incomplete recovery is common. Studies of hospitalized patients have shown that, while at least 50% of patients recover from an index episode within 6 months, 30% remain symptomatic for more than a year and 12% for more than 5 years.5

There is some evidence for an increase in the prevalence of major depression, and a younger age of onset, over the last 40 years.6

Aetiology

The aetiology of depression is complex, involving both genetic and environmental factors. Important environmental factors include childhood experiences of adversity or neglect, and stresses in adult life. The effect of genetic factors may be mediated in part through inherited predispositions to excessive worry and anxiety.3

Precipitating life events, especially those involving loss, are known to play a part in triggering individual episodes of depression.7 This effect is greatest for the first episode of depression. Second and subsequent episodes are more likely to occur without identifiable precipitating events,8 suggesting that the first episode has a neurobiological priming effect.9

Neurobiological changes in depression are also complex. Based in part on the supposed mechanism of action of antidepressant medication, early work focused on evidence of depletion of amine neurotransmitters in the central nervous system.10 More recent research has suggested depression may involve alterations in neural cell populations, especially in the hippocampus.11

Prevention

Depression is a major public health problem. The World Health Organization has determined that in 1990 depression was the fourth leading cause of disease burden in the world and that by 2020 it would be the second leading cause of disease burden.12 Public health measures have included campaigns to raise awareness of depression both in the general public and in healthcare providers. ED staff can play a very significant role in case identification and in ensuring referral for effective treatment.

Clinical features

Symptoms

At some point, the patient can be told that the interviewer would now like to explore the symptoms of depression in more detail. It may be helpful to group the symptoms of depressive episode (Table 20.4.1) into various domains of the patient’s experience. The first group (‘depressed mood’, ‘markedly diminished interest’, and ‘loss of energy’) refers to the pervasive mood state and the quality of the patient’s spirits or enthusiasm for life. The second group (‘loss of self-esteem’, ‘unreasonable self-reproach or guilt’, and ‘recurrent thoughts of death or suicide’) refers to the cognitive contents of the patient’s thoughts. The third group (‘diminished concentration’ and ‘psychomotor agitation or retardation’) refers to the degree of agitation or lethargy associated with the patient’s thought processes and physical activity. The final group (‘insomnia or hypersomnia’ and ‘change in appetite’) refers to physiological changes.

‘Markedly diminished interest or pleasure in all, or almost all, activities, most of the day, nearly every day’ is somewhat easier to assess, especially if the interviewer takes the time to build up a picture of the patient’s usual day. With careful inquiry a nuanced picture can be built up of the extent of the patient’s withdrawal from his or her usual activities. Included within this criterion is a lack of pleasure or interest in sexual activity, which in more severe cases can be experienced as a profound loss of sexual feelings.