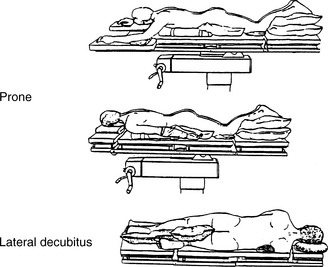

CHAPTER 20 Patient Positioning

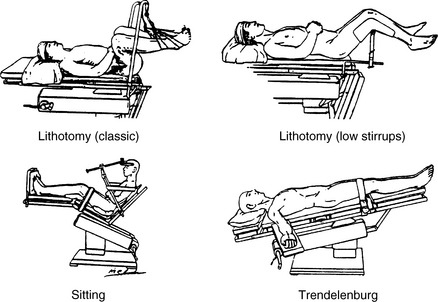

5 What nerves may be affected from lithotomy positioning?

Femoral nerve: A reasonable practice is to avoid hip flexion >90 degrees, although it remains a matter of debate whether extreme flexion predisposed the patient to a femoral neuropathy. The femoral nerve is also at risk from pelvic retractors.

Femoral nerve: A reasonable practice is to avoid hip flexion >90 degrees, although it remains a matter of debate whether extreme flexion predisposed the patient to a femoral neuropathy. The femoral nerve is also at risk from pelvic retractors.11 What are the advantages of the sitting position?

12 List the disadvantages of the sitting position

Hypotension. Because of decreased venous return, cardiac output may be reduced by as much as 20% but improves with fluid administration and pressors. Consider lower extremity compression hose to improve venous return. Intra-arterial monitoring is essential. Level the transducer at the level of the external auditory meatus to monitor cerebral perfusion pressure.

Hypotension. Because of decreased venous return, cardiac output may be reduced by as much as 20% but improves with fluid administration and pressors. Consider lower extremity compression hose to improve venous return. Intra-arterial monitoring is essential. Level the transducer at the level of the external auditory meatus to monitor cerebral perfusion pressure.19 How might upper extremity neuropathies be prevented through careful positioning?

KEY POINTS: Patient Positioning

1. A conscientious attitude toward positioning is required to facilitate the surgical procedure, prevent physiologic embarrassment, and prevent injury to the patient.

2. Postoperative blindness is increasing in frequency, but it is unclear exactly which patients are at risk. Although not a guarantee to prevent this complication, during lengthy spine procedures in the prone position maintain intravascular volume, hematocrit, and perfusion pressure.

3. The most common postoperative nerve injury is ulnar neuropathy. It is most commonly found in men older than 50 years, is delayed in presentation, is not invariably prevented by padding, and is multifactorial in origin.

4. In order of decreasing sensitivity, monitors for detection of VAE are transesophageal echocardiography and Doppler ultrasound > increases in end-tidal nitrogen fraction > decreases in end-tidal carbon dioxide > increases in right atrial pressure > esophageal stethoscope. It should be noted that, of all these monitors, only the right atrial catheter can treat a recognized air embolism.

24 How does the head position affect the position of the endotracheal tube with respect to the carina?

1. ASA Task Force Perioperative Blindness. Practice advisory for perioperative visual loss associated with spine surgery. Anesthesiology. 2006;104:1319-1328.

2. Lee L.A., Roth S., Posner K.L., et al. The American Society of Anesthesiologists postoperative visual loss registry: analysis of 93 spine surgery cases with postoperative visual loss. Anesthesiology. 2006;105:652-659.