CASE 20 No-Reflow After Coronary Intervention

Cardiac catheterization

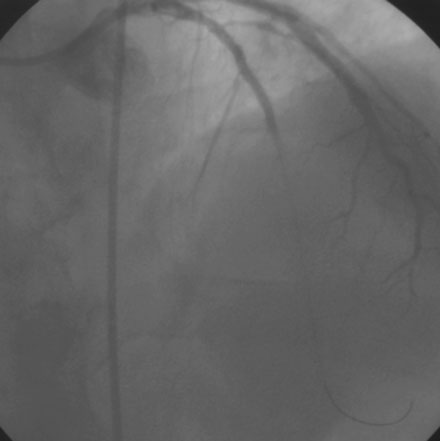

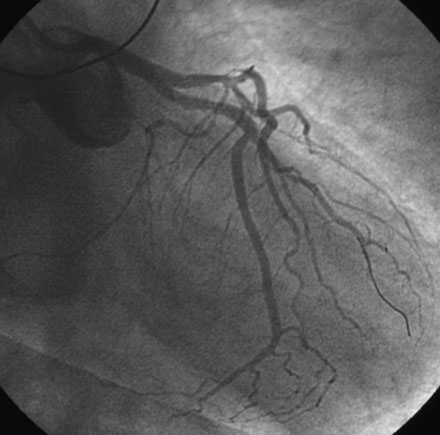

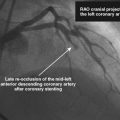

Diagnosed with a non-ST segment elevation acute myocardial infarction, he was admitted to a telemetry unit and treated with aspirin, enoxaparin, nitroglycerin, atorvastatin and metoprolol. He remained pain-free and underwent cardiac catheterization the following day. Left ventriculography was normal. Coronary angiography noted nonobstructive luminal irregularities in the right coronary and left circumflex arteries and severe narrowing in the proximal segment of the left anterior descending artery (Figure 20-1). Compared to the circumflex artery, angiographic flow appeared reduced at baseline (Video 20-1). After the intravenous administration of unfractionated heparin and eptifibatide, balloon angioplasty was performed using a 2.5 mm diameter by 20 mm long compliant balloon. Angiography performed after balloon dilatation showed complete occlusion of the left anterior descending artery at the site of the intervention (Video 20-2). The patient developed chest pressure but remained hemodynamically stable. An intracoronary bolus dose of 100 mcg of adenosine delivered through the guide catheter improved flow slightly; however, the entire artery did not fill with contrast (Video 20-3). There did not appear to be a dissection or other luminal problem responsible for the reduced flow, and the activated clotting time (ACT) was 280 seconds. The operator then deployed a tacrolimus-eluting stent (3.0 mm diameter by 28 mm long). Flow remained reduced, and the patient continued to experience chest pain after stenting despite repeated bolus injections of 100 mcg of adenosine (total of 500 mcg) injected through the guide catheter (Figure 20-2 and Video 20-4). At this point, the operator positioned an infusion catheter (Rapid Transit™ Catheter, Cordis Corporation) in the distal left anterior descending artery and injected an additional 100 μg adenosine. Subsequent angiography demonstrated nearly normal flow (Video 20-5) and the patient’s chest discomfort resolved.

Discussion

Although related, the dominant mechanism responsible for no reflow in these two settings differ.1,2 The no-reflow observed after reperfusion for an acute myocardial infarction is likely a consequence of ischemic microvascular dysfunction, myocardial edema, inflammation, and reperfusion injury; there also may be a component of distal embolization due to thrombus or necrotic plaque. No-reflow observed as a complication of percutaneous coronary intervention is usually due to microvascular obstruction from embolization of plaque components, platelets, and thrombi.

Coronary dissection, vasospasm, and air embolism may masquerade as no–reflow, and these conditions should be carefully excluded. Although the no-reflow phenomenon complicates less than 5% of all coronary interventions, there is a higher frequency of no-reflow following interventions associated with distal embolization, including saphenous vein graft lesions, atheroablative procedures such as rotational atherectomy, and coronary intervention performed in the setting of acute coronary syndromes. In addition, several plaque characteristics are associated with an increased risk of no-reflow (Table 20-1).1,2

TABLE 20-1 Characteristics Associated with No-Reflow After Coronary Intervention

| Angiographic Characteristics |

| Plaque ulceration |

| Thrombus |

| Long lesion length |

| Total coronary occlusion |

| Plaque Characteristics (by intravascular ultrasound) |

| Ruptured plaque |

| Large lipid pool |

| Thrombus |

| Large plaque burden |

Among pharmacologic agents successful at restoring or improving flow, intracoronary administration of nitroprusside (200 mcg), adenosine (24 to 1000 mcg), and verapamil (50 to 900 mcg) are most popular.3–5 Intracoronary nitroglycerin is not effective, primarily because of its lack of effect on the resistance arterioles. The platelet glycoprotein IIb/IIIa receptor antagonists have a role in preventing this complication in the setting of acute coronary syndrome, and distal protection devices reduce the no-reflow phenomenon in the case of saphenous vein graft interventions.

1 Jaffe R., Charron T., Puley G., Dick A., Strauss B.H. Microvascular obstruction and the no-reflow phenomenon after percutaneous coronary intervention. Circulation. 2008;117:3152-3156.

2 Rezkalla S.H., Kloner R.A. No-reflow phenomenon. Circulation. 2002;105:656-662.

3 Iijima R., Shinji H., Ikeda N., Itaya H., Makino K., Funatsu A., Yokouchi T., Komatsu H., Ito N., Nuruki H., Nakajima R., Nakamura M. Comparison of coronary arterial finding by intravascular ultrasound in patients with “transient no-reflow” versus “reflow” during percutaneous coronary intervention in acute coronary syndrome. Am J Cardiol. 2006;97:29-33.

4 Hillegass W.B., Dean N.A., Liao L., Rhinehart R.G., Myers P.R. Treatment of no-reflow and impaired flow with the nitric oxide donor nitroprusside following percutaneous coronary interventions: Initial human clinical experience. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;37:1335-1343.

5 Kelly R.V., Cohen M.G., Stouffer G.A. Incidence and management of “no-reflow” following percutaneous coronary interventions. Am J Med Sci. 2005;329:78-85.