CHAPTER 2 The Psychiatric Interview

OVERVIEW

A collaborative review of the formulation and differential diagnosis can provide a platform for developing (with the patient) options and recommendations for treatment, taking into account the patient’s amenability for therapeutic intervention.1 Few medical encounters are more intimate and potentially frightening and shameful than the psychiatric examination.2 As such, it is critical that the examiner create a safe space for the kind of deeply personal self-revelation required.

LESSONS FROM ATTACHMENT THEORY, NARRATIVE MEDICINE, AND MINDFUL PRACTICE

Healthy interactions with “attachment figures” in early life (e.g., parents) promote robust biological, emotional, and social development in childhood and throughout the life cycle.4 The foundations for attachment theory are based on research findings in cognitive neuroscience, genetics, and brain development that indicate an ongoing and life-long dance between an individual’s neural circuitry, genetic predisposition, brain plasticity, and environmental influences.5 Secure attachments in childhood foster emotional resilience6 and generate skills and habits of seeking out selected attachment figures for comfort, protection, advice, and strength. Relationships based on secure attachments lead to effective use of cognitive functions, emotional flexibility, enhancement of security, assignment of meaning to experiences, and effective self-regulation.5 In emotional relationships of many sorts, including the student-teacher and doctor-patient relationships, there may be many features of attachment present (such as seeking proximity, or using an individual as a “safe haven” for soothing and as a secure base).7

What promotes secure attachment in early childhood, and how may we draw from this in understanding a therapeutic doctor-patient relationship and an effective psychiatric interview? The foundations for secure attachment for children (according to Siegel) include several attributes ascribed to parents5 (Table 2-1).

We must always be mindful not to patronize our patients and to steer clear of the paternalistic power dynamics that could be implied in analogizing the doctor-patient relationship to one between parent and child; nonetheless, if we substitute “doctor” for “parent” and similarly substitute “patient” for “child,” we can immediately see the relevance to clinical practice. We can see how important each of these elements is in fostering a doctor-patient relationship that is open, honest, mutual, collaborative, respectful, trustworthy, and secure. Appreciating the dynamics of secure attachment also deepens the meaning of “patient-centered” care. The medical literature clearly indicates that good outcomes and patient satisfaction involve physician relationship techniques that involve reflection, empathy, understanding, legitimization, and support.8,9 Patients reveal more about themselves when they trust their doctors, and trust has been found to relate primarily to behavior during clinical interviews9 rather than to any preconceived notion of competence of the doctor or behavior outside the office.

Particularly important in the psychiatric interview is the facilitation of a patient’s narrative. The practice of narrative medicine involves an ability to acknowledge, absorb, interpret, and act on the stories and struggles of others.10 Charon10 describes the process of listening to patients’ stories as a process of following the biological, familial, cultural, and existential thread of the situation. It encompasses recognizing the multiple meanings and contradictions in words and events; attending to the silences, pauses, gestures, and nonverbal cues; and entering the world of the patient, while simultaneously arousing the doctor’s own memories, associations, creativity, and emotional responses—all of which are seen in some way by the patient.10 Narratives, like all stories, are co-created by the teller and the listener. Storytelling is an age-old part of social discourse that involves sustained attention, memory, emotional responsiveness, nonverbal responses and cues, collaborative meaning-making, and attunement to the listener’s expectations. It is a vehicle for explaining behavior. Stories and storytelling are pervasive in society as a means of conveying symbolic activity, history, communication, and teaching.5 If a physician can assist the patient in telling his or her story effectively, reliable and valid data will be collected and the relationship solidified. Narratives are facilitated by authentic, compassionate, and genuine engagement.

Creating the optimal conditions for a secure attachment and the elaboration of a coherent narrative requires mindful practice. Just as the parent must be careful to differentiate his or her emotional state and needs from the child’s and be aware of conflicts and communication failures, so too must the mindful practitioner. Epstein11 notes that mindful practitioners attend in a nonjudgmental way to their own physical and mental states during the interview. Their critical self-reflection allows them to listen carefully to a patient’s distress, to recognize their own errors, to make evidence-based decisions, and to stay attuned to their own values so that they may act with compassion, technical competence, and insight.11

THE CONTEXT OF THE INTERVIEW: FACTORS INFLUENCING THE FORM AND CONTENT OF THE INTERVIEW

All interviews occur in a context. Awareness of the context may require modification of clinical interviewing techniques. There are four elements to consider: the setting, the situation, the subject, and the significance.12

The Setting

Patients are exquisitely sensitive to the environment in which they are evaluated. There is a vast difference between being seen in an emergency department (ED), on a medical floor, on an inpatient or partial hospital unit, in a psychiatric outpatient clinic, in a private doctor’s office, in a school, or in a court clinic. Each setting has its benefits and downsides, and these must be assessed by the evaluator. For example, in the ED or on a medical or surgical floor, space for private, undisturbed interviews is usually inadequate. Such settings are filled with action, drama, and hospital personnel who race around. ED visits may require long waits, and contribute to impersonal approaches to patients and negative attitudes to psychiatric patients. For a patient with borderline traits who is in crisis, this can only create extreme frustration and possibly exacerbation of chronic fears of deprivation, betrayal, abandonment, and aloneness, and precipitation of regression.13 For these and higher functioning patients, the public nature of the environment and the frantic pace of the emergency service may make it difficult for the patient to present very personal, private material in a calm fashion. In other public places (such as community health centers or schools), patients may feel worried about being recognized by neighbors or friends. Whatever the setting, it is always advisable to ask the patient directly how comfortable he or she feels in the examining room, and to try to ensure privacy and a quiet environment with minimal distractions.

The Situation

Other patients may come reluctantly or even with great resistance. Many arrive at the request or demand of a loved one, friend, colleague, or employer because of behaviors deemed troublesome. The patient may deny any problem, or simply be too terrified to confront a condition that is bizarre, unexplainable, or “mental.” Some conditions are ego-syntonic, such as anorexia nervosa. A patient with this eating disorder typically sees the psychiatrist as the enemy—as a doctor that wants to make her “get fat.” For resistant patients, it is often very useful to address the issue up front. With an anorexic patient referred by her internist and brought in by family, one could begin by saying, “Hi, Ms. Jones. I know you really don’t want to be here. I understand that your doctor and family are concerned about your weight. I assure you that my job is first and foremost to understand your point of view. Can you tell me why you think they wanted you to see me?” Another common situation with extreme resistance is the alcoholic individual brought in by a spouse or friend, clearly in no way ready to stop drinking. In this case you might say, “Good morning, Mr. Jones. I heard from your wife that she is really concerned about your drinking, and your safety, especially when driving. First, let me tell you that neither I nor anyone else can stop you from drinking. That is not my mission today. I do want to know what your drinking pattern is, but more, I want to get the picture of your entire life to understand your current situation.” Extremely resistant patients may be brought involuntarily to an emergency service, often in restraints, by police or ambulance, because they are considered dangerous to themselves or others. It is typically terrifying, insulting, and humiliating to be physically restrained. Regardless of the reasons for admission, unknown to the psychiatrist, it is often wise to begin the interview as follows: “Hi, Ms. Carter, my name is Dr. Beresin. I am terribly sorry you are strapped down, but the police and your family were very upset when you locked yourself in the car and turned on the ignition. They found a suicide note on the kitchen table. Everyone was really concerned about your safety. I would like to discuss what is going on, and see what we can do together to figure things out.”

The Subject

Adolescents raise additional issues. While some may come willingly, others are dragged in against their will. In this instance, it is very important to identify and to empathize with the teenager: “Hi, Tony. I can see this is the last place you want to be. But now that you are hauled in here by your folks, we should make the best of it. Look, I have no clue what is going on, and don’t even know if you are the problem! Why don’t you tell me your story?” Teenagers may indeed feel like hostages. They may have bona fide psychiatric disorders, or may be stuck in a terrible home situation. The most important thing the examiner must convey is that the teenager’s perspective is important, and that this will be looked at, as well as the parent’s point of view. It is also critical to let adolescents, as all patients, know about the rules and limits of confidentiality. Many children think that whatever they say will be directly transmitted to their parents. Surely this is their experience in school. However, there are clear guidelines about adolescent confidentiality, and these should be delineated at the beginning of the clinical encounter. Confidentiality is a core part of the evaluation, and it will be honored for the adolescent; it is essential that this is communicated to them so they may feel safe in divulging very sensitive and private information without fears of repercussion. Issues such as sexuality, sexually transmitted diseases, substance abuse, and issues in mental health are protected by state and federal statutes. There are, however, exceptions; one major exception is that if the patient or another is in danger by virtue of an adolescent’s behavior, confidentiality is waived.14

The Significance

Psychiatric disorders are commonly stigmatized, and subsequently are often accompanied by profound shame, anxiety, denial, fear, and uncertainty. Patients generally have a poor understanding of psychiatric disorders, either from lack of information, myth, or misinformation from the media (e.g., TV, radio, and the Internet).15 Many patients have preconceived notions of what to expect (bad or good), based on the experience of friends or family. Some patients, having talked with others or having searched online, may be certain or very worried that they suffer from a particular condition, and this may color the information presented to an examiner. A specific syndrome or symptom may have idiosyncratic significance to a patient, perhaps because a relative with a mood disorder was hospitalized for life, before the deinstitutionalization of mental disorders. Hence, he or she may be extremely wary of divulging any indication of severe symptoms lest life-long hospitalization result. Obsessions or compulsions may be seen as clear evidence of losing one’s mind, having a brain tumor, or becoming like Aunt Jesse with a chronic psychosis.12 Some patients (based on cognitive limitations) may not understand their symptoms. These may be normal, such as the developmental stage in a school-age child, whereas others may be a function of mental retardation, Asperger’s syndrome, or cerebral lacunae secondary to multiple infarcts following embolic strokes.

Finally, there are significant cultural differences in the way mental health and mental illness are viewed. Culture may influence health-seeking and mental health–seeking behavior, the understanding of psychiatric symptoms, the course of psychiatric disorders, the efficacy of various treatments, or the kinds of treatments accepted.16 Psychosis, for example, may be viewed as possession by spirits. Some cultural groups have much higher completion rates for suicide, and thus previous attempts in some individuals should be taken more seriously. Understanding the family structure may be critical to the negotiation of treatment; approval by a family elder could be crucial in the acceptance of professional help.

ESTABLISHING AN ALLIANCE AND FOSTERING EFFECTIVE COMMUNICATION

Studies of physician-patient communication have demonstrated that good outcomes flow from effective communication; developing a good patient-centered relationship is characterized by friendliness, courtesy, empathy, and partnership building, and by the provision of information. Posi-tive outcomes have included benefits to emotional health, symptom resolution, and physiological measures (e.g., blood pressure, blood glucose level, and pain control).17–20

In 1999 leaders and representatives of major medical schools and professional organizations convened at the Fetzer Institute in Kalamazoo, Michigan, to propose a model for doctor-patient communication that would lend itself to the creation of curricula for medical and graduate medical education, and for the development of standards for the profession. The goals of the Kalamazoo Consensus Statement21 were to foster a sound doctor-patient relationship and to provide a model for the clinical interview. The key elements of this statement are summarized in Table 2-2, and are applicable to the psychiatric interview.

Table 2-2 Building a Relationship: The Fundamental Tasks of Communication

|

• Maintain an awareness that feelings, ideas, and values of both the patient and the doctor influence the relationship.

|

BUILDING THE RELATIONSHIP AND THERAPEUTIC ALLIANCE

All psychiatric interviews must begin with a personal introduction, and establish the purpose of the interview; this helps create an alliance around the initial examination. The interviewer should attempt to greet the person warmly, and use words that demonstrate care, attention, and concern. Note taking and use of computers should be minimized, and if used, should not interfere with ongoing eye contact. The interviewer should indicate that this interaction is collaborative, and that any misunderstandings on the part of patient or physician should be immediately clarified. In addition, the patient should be instructed to ask questions, interrupt, and provide corrections or additions at any time. The time frame for the interview should be announced. In general, the interviewer should acknowledge that some of the issues and questions raised will be highly personal, and that if there are issues that the patient has real trouble with, he or she should let the examiner know. Confidentiality should be assured at the outset of the interview. These initial guidelines set the tone, quality, and style of the clinical interview. An example of a beginning is, “Hi, Mr. Smith. My name is Dr. Beresin. I am delighted you came today. I would like to discuss some of the issues or problems you are dealing with so that we can both understand them better, and figure out what kind of assistance may be available. I will need to ask you a number of questions about your life, both your past and present, and if I need some clarification about your descriptions I will ask for your help to be sure I ‘get it.’ If you think I have missed the boat, please chime in and correct my misunderstanding. Some of the topics may be highly personal, and I hope that you will let me know if things get a bit too much. We will have about an hour to go through this, and then we’ll try to come up with a reasonable plan together. I do want you to know that everything we say is confidential. Do you have any questions about our job today?” This should be followed with an open-ended question about the reasons for the interview.

For many patients, the psychiatric interview is probably one of the most confusing examinations in medicine. The psychiatric interview is at once professional and profoundly intimate. We are asking patients to reveal parts of their life they may only have shared with extremely close friends, a spouse, clergy, or family, if anyone. And they are coming into a setting in which they are supposed to do this with a total stranger. Being a doctor may not be sufficient to allay the apprehension that surrounds this situation; being a trustworthy, caring human being may help a great deal. It is vital to make the interview highly personal and to use techniques that come naturally. Beyond affirming and validating the patient’s story with extreme sensitivity, some clinicians may use humor and judicious self-revelation. These elements are characteristics of healers.22

As noted earlier, reliable mirroring of the patient’s cognitive and emotional state and self-reflection of one’s affective response to patients are part and parcel of establishing secure attachments. Actively practicing self-reflection and clarifying one’s understanding helps to model behavior for the patient, as the doctor and patient co-create the narrative. Giving frequent summaries to “check in” on what the physician has heard may be very valuable, particularly early on in the interview, when the opening discussion or chief complaints are elicited. For example, a 22-year-old woman gradually developed obsessive-compulsive symptoms over the past 2 years that led her to be housebound. The interviewer said, “So, Ms. Thompson, let’s see if I get it. You have been stuck at home and cannot get out of the house because you have to walk up and down the stairs for a number of hours. If you did not ‘get it right,’ something terrible would happen to one of your family members. You also noted that you were found walking the stairs in public places, and that even your friends could not understood this behavior, and they made fun of you. You mentioned that you had to ‘check’ on the stove and other appliances being turned off, and could not leave your car, because you were afraid it would not turn off, or that the brake was not fully on, and again, something terrible would happen to someone. And you said to me that you were really upset because you knew this behavior was ‘crazy.’ How awful this must be for you! Did I get it right?” The examiner should be sure to see both verbally and nonverbally that this captured the patient’s problem. If positive feedback did not occur, the examiner should attempt to see if there was a misinterpretation, or if the interviewer came across as judgmental or critical. One could “normalize” the situation and reassure the patient to further solidify the alliance by saying, “Ms. Thompson, your tendency to stay home, stuck, in the effort to avoid hurting anyone is totally natural given your perception and concern for others close to you. I do agree, it does not make sense, and appreciate that it feels bizarre and unusual. I think we can better understand this behavior, and later I can suggest ways of coping and maybe even overcoming this situation through treatments that have been quite successful with others. However, I do need to get some additional information. Is that OK?” In this way, the clinician helps the patient feel understood—that anyone in that situation would feel the same way, and that there is hope. But more information is needed. This strategy demonstrates respect and understanding, and provides support and comfort, while building the alliance.

DATA COLLECTION: BEHAVIORAL OBSERVATION, THE MEDICAL AND PSYCHIATRIC HISTORY, AND MENTAL STATUS EXAMINATION

The Medical and Psychiatric History

Table 2-3 provides an overview of the key components of the psychiatric history.

| Identifying Information |

| Name, address, phone number, and e-mail address Insurance Age, gender, marital status, occupation, children, ethnicity, and religion For children and adolescents: primary custodians, school, and grade Primary care physician Psychiatrist, allied mental health providers Referral source Sources of information Reliability |

| Chief Complaint/Presenting Problem(s) |

| History of Present Illness |

| Onset Perceived precipitants Signs and symptoms Course and duration Treatments: professional and personal Effects on personal, social, and occupational or academic function Co-morbid psychiatric or medical disorders Psychosocial stressors: personal (psychological, medical), family, friends, work/school, legal, housing, and financial |

| Past Psychiatric History |

| Previous Episodes of the Problem(s) |

| Symptoms, course, duration, and treatment (inpatient or outpatient) |

| Psychiatric Disorders |

| Symptoms, course, duration, and treatment (inpatient or outpatient) |

| Past Medical History |

| Medical problems: past and current Surgical problems: past and current Accidents Allergies Immunizations Current medications: prescribed and over-the-counter medications Other treatments: acupuncture, chiropractic, homeopathic, yoga, and meditation Tobacco: present and past use Substance use: present and past use Pregnancy history: births, miscarriages, and abortions Sexual history: birth control, safe sex practices, and history of, and screening for, sexually transmitted diseases |

| Review of Systems |

| Family History |

| Family psychiatric history Family medical history |

| Personal History: Developmental and Social History |

| Early Childhood |

| Developmental milestones Family relationships |

| Middle Childhood |

| School performance Learning or attention problems Family relationships Friends Hobbies |

| Adolescence |

| School performance (include learning and attention problems) Friends and peer relationships Family relationships Psychosexual history Dating and sexual history Work history Substance use Problems with the law |

| Early Adulthood |

| Education Friends and peer relationships Hobbies and interests Marital and other romantic partners Occupational history Military experiences Problems with the law |

| Midlife and Older Adulthood |

| Career development Marital and other romantic partners Changes in the family Losses Aging process: psychological and physical |

Adapted from Beresin EV: The psychiatric interview. In Stern TA, editor: The ten-minute guide to psychiatric diagnosis and treatment, New York, 2005, Professional Publishing Group.

Presenting Problems

The interviewer should begin with the presenting problem using open-ended questions. The patient should be encouraged to tell his or her story without interruptions. Many times the patient will turn to the doctor for elaboration, but it is best to let the patient know that he or she is the true expert and that only he or she has experienced this situation directly. It is best to use clarifying questions throughout the interview. For example, “I was really upset and worked up” may mean one thing to the patient and something else to an examiner. It could mean frustrated, anxious, agitated, violent, or depressed. Such a statement requires clarification. So, too, does a comment such as “I was really depressed.” Depression to a psychiatrist may be very different for a patient. To some patients, depression means aggravated, angry, or sad. It might be a momentary agitated state, or a chronic state. Asking more detailed questions not only clarifies the affective state of the patient, but also transmits the message that he or she knows best and that a real collaboration and dialogue is the only way we will figure out the problem. In addition, once the patient’s words are clarified it is very useful to use the patient’s own words throughout the interview to verify that you are listening.23

In discussing the presenting problems, it is best to avoid a set of checklist-type questions, but one should cover the bases to create a Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, Fourth Edition, Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR) differential diagnosis. It is best to focus largely on the chief complaint and present problems and to incorporate other parts of the history around this. The presenting problem is the reason for a referral, and is probably most important to the patient, even though additional questions about current function and the past medical or past psychiatric history may be more critical to the examiner. A good clinician, having established a trusting relationship, can always redirect a patient to ascertain additional information (such as symptoms not mentioned by the patient and the duration, frequency, and intensity of symptoms). Also it is important to ask how the patient has coped with the problem, and what is being done personally or professionally to help it. One should ask if there are other problems or stressors, medical problems, or family issues that exacerbate the current complaint. After a period of open-ended questions about the current problem, the interviewer should ask questions about mood, anxiety, and other behavioral problems and how they affect the presenting problem. A key part of the assessment of the presenting problem should be a determination of safety. Questions about suicide, homicide, domestic violence, and abuse should not be omitted from a review of the current situation. Finally, one should ascertain why the patient came for help now, how motivated he or she is for getting help, and how the patient is faring in personal, family, social, and professional life. Without knowing more, since this is early in the interview, the examiner should avoid offering premature reassurance, but provide support and encouragement for therapeutic assistance that will be offered in the latter part of the interview.

Past Psychiatric History

After the opening phases of the interview, open-ended questions may shift to more focused questions. In the past psychiatric history, the interviewer should inquire about previous DSM-IV-TR Axis I and II diagnoses (including the symptoms of each, partial syndromes, how they were managed, and how they affected the patient’s life). A full range of treatments, including outpatient, inpatient, and partial hospital, should be considered. It is most useful to ask what treatments, if any, were successful, and if so, in what ways. By the same token, the examiner should ask about treatment failures. This, of course, will contribute to the treatment recommendations provided at the close of the interview. This may be a good time in the interview to get a sense of how the patient copes under stress. What psychological, behavioral, and social means are employed in the service of maintaining equilibrium in the face of hardship? It is also wise to focus not just on coping skills, defenses, and adaptive techniques in the face of the psychiatric disorder, but also on psychosocial stressors in general (e.g., births, deaths, loss of jobs, problems in relationships, and problems with children). Discerning a patient’s coping style may be highly informative and contribute to the psychiatric formulation. Does the patient rely on venting emotions, on shutting affect off and wielding cognitive controls, on using social supports, on displacing anger onto others, or on finding productive distractions (e.g., plunging into work)? Again, knowing something about a person’s style of dealing with adversity uncovers defense mechanisms, reveals something about personality, and aids in the consideration of treatment options. For example, a person who avoids emotion, uses reason, and sets about to increase tasks in hard times may be an excellent candidate for a cognitive-behavioral approach to a problem. An individual who thrives through venting emotions, turning to others for support, and working to understand the historical origins of his or her problems may be a good candidate for psychodynamic psychotherapy, either individual or group.

Use of Corollary Information

Obtaining consent to contact others in a patient’s life is useful not only for information gathering, but for the involvement of others in the treatment process, if needed. For children and adolescents, this is absolutely essential, as is obtaining information from teachers or other school personnel. Contacting the patient’s primary care physician or therapist may be useful for objective assessment of the medical and psychiatric history, as well as for corroboration of associated conditions, doses of medications, and past laboratory values. Finally, it is always useful to review the medical record (if accessible, and with permission).

The Mental Status Examination

The mental status examination is part and parcel of any medical and psychiatric interview. Its traditional components are indicated in Table 2-4. Most of the data needed in this model can be ascertained by asking the patient about elements of the current problems. Specific questions may be needed for the evaluation of perception, thought, and cognition. Most of the information in the mental status examination is obtained by simply taking the psychiatric history and by observing the patient’s behavior, affect, speech, mood, thought, and cognition.

| General appearance and behavior: grooming, posture, movements, mannerisms, and eye contact |

| Speech: rate, flow, latency, coherence, logic, and prosody |

| Affect: range, intensity, lability |

| Mood: euthymic, elevated, depressed, irritable, anxious |

| Perception: illusions and hallucinations |

| Thought (coherence and lucidity): form and content (illusions, hallucinations, and delusions) |

| Safety: suicidal, homicidal, self-injurious ideas, impulses, and plans |

| Cognition |

Thought disorders may manifest with difficulties in the form or content of thought. Formal thought disorders involve the way ideas are connected. Abnormalities in form may involve the logic and coherence of thinking. Such disorders may herald neurological disorders, severe mood disorders (e.g., psychotic depression or mania), schizophreniform psychosis, delirium, or other disorders that impair reality testing. Examples of formal thought disorders are listed in Table 2-5.24,25

Table 2-5 Examples of Formal Thought Disorders

Disorders of the content of thought pertain to the specific ideas themselves. The examiner should always inquire about paranoid, suicidal, and homicidal thinking. Other indications of disorder of thought content include delusions, obsessions, and ideas of reference (Table 2-6).25

Table 2-6 Disorders of Thought Content

The cognitive examination includes an assessment of higher processes of thinking. This part of the examination is critical for a clinical assessment of neurological function, and is useful for differentiating focal and global disorders, delirium, and dementia. The traditional model assesses a variety of dimensions (Table 2-7).26

Table 2-7 Categories of the Mental Status Examination

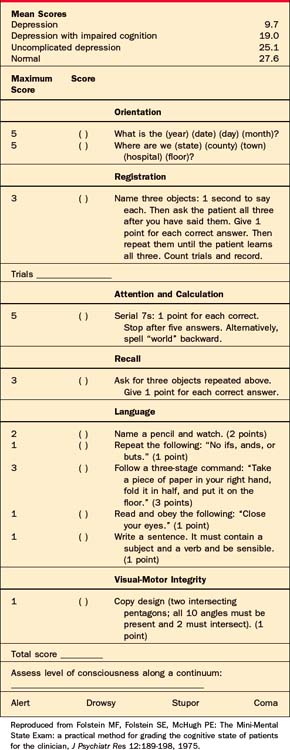

Alternatively, the Mini-Mental State Examination27 may be administered (Table 2-8). It is a highly valid and reliable instrument that takes about 5 minutes to perform and is very effective in differentiating depression from dementia.

SHARING INFORMATION AND PREPARING THE PATIENT FOR TREATMENT

The conclusion of the psychiatric interview requires summarizing the symptoms and history and organizing them into a coherent narrative that can be reviewed and agreed on by the patient and the clinician. This involves recapitulating the most important findings and explaining the meaning of them to the patient. It is crucial to obtain an agreement on the clinical material and the way the story holds together for the patient. If the patient does not concur with the summary, the psychiatrist should return to the relevant portions of the interview in question and revisit the topics that are in disagreement.

Education about treatment should include reviewing the pros and cons of various options. This is a good time to dispel myths about psychiatric treatments, either pharmacotherapy or psychotherapy. Both of these domains have significant stigma associated with them. For patients who are prone to shun pharmacotherapy (not wanting any “mind-altering” medications), it may be useful to “medicalize” the psychiatric disorder and note that common medical conditions involve attention to biopsychosocial treatment.12 For example, few people would refuse medications for treatment of hypertension, even though it may be clear that the condition is exacerbated by stress and lifestyle. The same may be said for the treatment of asthma, migraines, diabetes, and peptic ulcers. In this light, the clinician can refer to psychiatric conditions as problems of “chemical imbalances”—a neutral term—or as problems with the brain, an organ people often forget when talking about “mental” conditions. A candid dialogue in this way, perhaps describing how depression or panic disorder involves abnormalities in brain function, may help. It should be noted that this kind of discussion should in no way be construed or interpreted as pressure—rather as an educational experience. Letting the patient know that treatment decisions are collaborative and patient-centered is absolutely essential in a discussion of this order.

THE EVALUATION OF CHILDREN AND ADOLESCENTS

Adolescents produce their own set of issues and problems for the interviewer.28 A teenager may or may not be brought in by a parent. However, given the developmental processes that surround the quests for identity and separation, the interviewer must treat the teen with the same kind of respect and collaboration as with an adult. The issue and importance of ensuring confidentiality have been mentioned previously. The adolescent also needs to hear at the outset that the interviewer would need to obtain permission to speak with parents or guardians, and that any information received from them would be faithfully transmitted to the patient.

DIFFICULTIES AND ERRORS IN THE PSYCHIATRIC INTERVIEW

Dealing with Sensitive Subjects

In other situations that are dangerous (such as occurs with suicidal, homicidal, manic, or psychotic patients), in which pertinent symptoms must be ascertained, questioning is crucial no matter how distressed the patient may become. In some instances when danger seems highly likely, hospitalization may be necessary for observation and further exploration of a serious disorder. Similarly, an agitated patient who needs to be assessed for safety may need sedation or hospitalization in order to complete a comprehensive evaluation, particularly if the cause of agitation is not known and the patient is not collaborating with the evaluative process.

Errors in Psychiatric Interviewing

Common mistakes made in the psychiatric interview are provided in Table 2-9.

1 Gordon C, Reiss H. The formulation as a collaborative conversation. Harvard Rev Psychiatry. 2005;13:112-123.

2 Lazare A. Shame and humiliation in the medical encounter. Arch Intern Med. 1987;147:1653-1658.

3 Garrett M;1998, Bear & Co Rochester, VT 145

4 Parkes CM, Stevenson-Hinde J, Marris P, editors. Attachment across the life cycle. London: Routledge, 1991.

5 Siegel DJ. Thmind: toward a neurobiology of interpersonal experience. New York: Guilford Press, 1999.

6 Rutter M. Clinical implications of attachment concepts: retrospect and prospect. In: Atkinson L, Zucker KJ, editors. Attachment and psychopathology. New York: Guilford Press, 1997.

7 Lieberman AF. Toddlers’ internalization of maternal attribution as a factor in quality of attachment. In: Atkinson L, Zucker KJ, editors. Attachment and psychopathology. New York: Guilford Press, 1997.

8 Lipkin M, Frankel RM, Beckman HB, et al. Performing the medical interview. In: Lipkin MJr, Putnam SM, Lazare A, editors. The medical interview: clinical care, education and research. New York: Springer-Verlag, 1995.

9 Lipkin MJr. Sisyphus or Pegasus? The physician interviewer in the era of corporatization of care. Ann Intern Med. 1996;124:511-513.

10 Charon R. Narrative medicine: a model for empathy, reflection, profession and trust. JAMA. 2001;286:1897-1902.

11 Epstein RM. Mindful practice. JAMA. 2004;291:2359-2366.

12 Beresin EV. The psychiatric interview. In: Stern TA, editor. The ten-minute guide to psychiatric diagnosis and treatment. New York: Professional Publishing Group, 2005.

13 Beresin EV, Gordon C. Emergency ward management of the borderline patient. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1981;3:237-244.

14 Confidential health care for adolescents: position paper of the Society for Adolescent Medicine. Prepared by Ford C, English A, Sigman. J Adolesc Health. 2004;35:160-167.

15 Butler JR, Hyler S. Hollywood portrayals of child and adolescent mental health treatment: implications for clinical practice. Child Adolesc Psychiatric Clin North Am. 2005;14:509-522.

16 Mintzer JE, Hendrie HC, Warchal EF. Minority and sociocultural issues. In: Sadock BJ, Sadock VA, editors. Kaplan and Sadock’s comprehensive textbook of psychiatry. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2005.

17 Stewart MA. Effective physician-patient communication and health outcomes: a review. CMAJ. 1995;152:1423-1433.

18 Simpson M, Buckman R, Stewart M, et al. Doctor-patient communication: the Toronto consensus statement. BMJ. 1991;303:1385-1387.

19 Williams S, Weinman J, Dale J. Doctor-patient communication and patient satisfaction: a review. Fam Pract. 1998;15:480-492.

20 Ong LML, De Haes CJM, Hoos AM, Lammes FB. Doctor-patient communication: a review of the literature. Soc Sci Med. 1995;40:903-918.

21 Participants in the Bayer-Fetzer Conference on Physician-Patient Communication in Medical Education: Essential elements of communication in medical encounters: the Kalamazoo Consensus Statement. Acad Med. 2001;76:390-393.

22 Novack DH, Epstein RM, Paulsen RH. Toward creating physician-healers: fostering medical students’ self-awareness, personal growth, and well-being. Acad Med. 1999;74:516-520.

23 Gordon C, Goroll A. Effective psychiatric interviewing in primary care medicine. In Stern TA, Herman JB, Slavin PL, editors: Massachusetts General Hospital guide in primary care psychiatry, ed 2, New York: McGraw-Hill, 2004.

24 Scheiber SC. The psychiatric interview, psychiatric history, and mental status examination. In: Hales RE, Yudofsky SC, editors. The American Psychiatric Press synopsis of psychiatry. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press, 1996.

25 Sadock BJ. Signs and symptoms in psychiatry. In: Sadock BJ, Sadock VA, editors. Kaplan and Sadock’s comprehensive text-book of psychiatry. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2005.

26 Silberman EK, Certa K. The psychiatric interview: settings and techniques. In Tasman A, Kay J, Lieberman J, editors: Psychiatry, ed 2, Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 2004.

27 Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PE. The Mini-Mental State Exam: a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:189-198.

28 Beresin EV, Schlozman SC. Psychiatric treatment of adolescents. In: Sadock BJ, Sadock VA, editors. Kaplan and Sadock’s comprehensive textbook of psychiatry. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2005.