Part 2 Pain Assessment and Management

Children’s ability to describe pain changes as they grow older and as they cognitively and linguistically mature. Three types of measures—behavioral, physiologic, and self-report—have been developed to measure children’s pain, and their applicability depends on the child’s cognitive and linguistic ability.

DEVELOPMENTAL CHARACTERISTICS OF CHILDREN’S RESPONSES TO PAIN

Preterm Infant

1. The preterm infant’s response may be behaviorally blunted or absent; however, there is sufficient evidence that preterm infants are neurologically capable of experiencing pain.

2. Use a preterm infant pain scale.

3. Assume that painful procedures in older child and adult are also painful in preterm infant (e.g., venipuncture, lumbar puncture, endotracheal intubation, circumcision, chest tube insertion, heel puncture).

Young Infant

1. Generalized body response of rigidity or thrashing, possibly with local reflex withdrawal of stimulated area

3. Facial expression of pain (brows lowered and drawn together, eyes tightly closed, and mouth open and squarish)

4. No association demonstrated between approaching stimulus and subsequent pain

Young Child

2. Verbal expressions such as “Ow,” “Ouch,” “It hurts”

4. Attempts to push stimulus away before it is applied

5. Lack of cooperation; need for physical restraint

6. Requests termination of procedure

7. Clings to parent, nurse, or other significant person

8. Requests emotional support, such as hugs or other forms of physical comfort

9. May become restless and irritable with continuing pain

10. Behaviors occurring in anticipation of actual painful procedure

School-Age Child

1. May see all behaviors of young child, especially during actual painful procedure, but less in anticipatory period

2. Stalling behavior, such as “Wait a minute” or “I’m not ready”

3. Muscular rigidity, such as clenched fists, white knuckles, gritted teeth, contracted limbs, body stiffness, closed eyes, wrinkled forehead

NONPHARMACOLOGIC STRATEGIES FOR PAIN MANAGEMENT

General Strategies

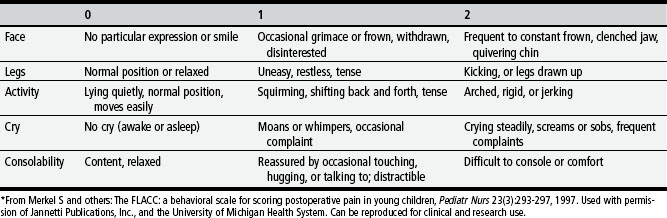

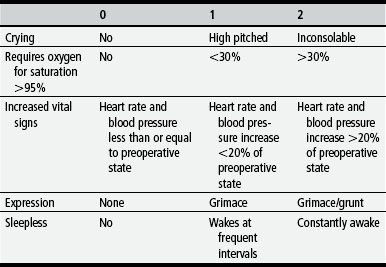

TABLE 2-1 Behavioral Pain Assessment Scales for Infants and Young Children

| AGES OF USE | INSTRUMENT |

|---|---|

| 4 months to 18 years | Objective Pain Score (OPS) (Hannallah and others, 1987) |

| 1 to 5 years | Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario Pain Scale (CHEOPS) (McGrath and others, 1985) |

| Newborn to 16 years | Nurses Assessment of Pain Inventory (NAPI) (Stevens, 1990) |

| 3 to 36 months | Behavioral Pain Score (BPS) (Robieux and others, 1991) |

| 4 to 6 months | Modified Behavioral Pain Scale (MBPS) (Taddio and others, 1995) |

| <36 months and children with cerebral palsy | Riley Infant Pain Scale (RIPS) (Schade and others, 1996) |

| 2 months to 7 years | FLACC Postoperative Pain Tool (Merkel and others, 1997) |

| 1 to 7 months | Postoperative Pain Score (POPS) (Attia and others, 1987) |

| Average gestational age 33.5 weeks | Neonatal Infant Pain Scale (NIPS) (Lawrence and others, 1993) |

| 27 weeks gestational age to full term | Pain Assessment Tool (PAT) (Hodgkinson and others, 1994) |

| 1 to 36 months | Pain Rating Scale (PRS) (Joyce and others, 1994) |

| 32 to 60 weeks gestational age | CRIES (Krechel, Bildner, 1995) |

| 28 to 40 weeks gestational age | Premature Infant Pain Profile (PIPP) (Stevens and others, 1996) |

| 0 to 28 days | Scale for Use in Newborns (SUN) (Blauer, Gerstmann, 1998) |

| Birth (23 weeks gestational age) and full-term newborns up to 100 days | Neonatal Pain, Agitation, and Sedation Scale (NPASS) (Puchalski, Hummel, 2002) |

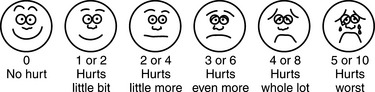

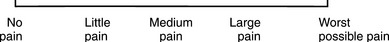

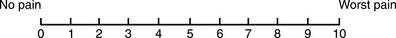

TABLE 2-3 Pain Rating Scales for Children

| PAIN SCALE, DESCRIPTION | RECOMMENDED AGE, COMMENTS |

|---|---|

Children as young as three years. Use original instructions without affect words, such as happy or sad, or brief words resulted in same range of pain rating, probably reflecting child’s rating of pain intensity. For coding purposes, numbers 0,2, 4,6, 8,10 can be substituted for 0-5 system to accommodate 0-10 system.

Provides three scales in one: facial expressions, numbers, and words.

Research supports cultural sensitivity of FACES for Caucasian, African-American, Hispanic, Thai, Chinese, and Japanese children.

Oucher (Beyer, Denyes, and Villarruel, 1992)

Uses six photographs of Caucasian child’s face representing “no hurt” to “biggest hurt you could ever have”; also includes vertical scale with numbers from 0 to 100; scales for African-American and Hispanic children have been developed (Villarruel and Denyes, 1991)

Children 3 to 13 years. Use numeric scale if child can count any 2 numbers, or by tens (Jordan-Marsh and others, 1994).

Determine whether child has cognitive ability to use photographic scale; child should be able to rate 6 geometric shapes from largest to smallest.

Determine which ethnic version of Oucher to use. Allow child to select version of Oucher, or use version that most closely matches physical characteristics of child.

NOTE: Ethnically similar scale may not be preferred by child when given choice of ethnically neutral cartoon scale (Luffy and Grove, 2003).

1. Use nonpharmacologic interventions to supplement, not replace, pharmacologic interventions, and use for mild pain and pain that is reasonably well controlled with analgesics.

2. Form a trusting relationship with child and family. Express concern regarding their reports of pain, and intervene appropriately.

3. Use general guidelines to prepare child for procedure.

4. Prepare child before potentially painful procedures, but avoid “planting” the idea of pain. For example, instead of saying, “This is going to (or may) hurt,” say, “Sometimes this feels like pushing, sticking, or pinching, and sometimes it doesn’t bother people. Tell me what it feels like to you.”

5. Use “nonpain” descriptors when possible (e.g., “It feels like heat” rather than “It’s a burning pain”). This allows for variation in sensory perception, avoids suggesting pain, and gives the child control in describing reactions.

6. Avoid evaluative statements or descriptions (e.g., “This is a terrible procedure” or “It really will hurt a lot”).

7. Stay with child during a painful procedure.

8. Allow parents to stay with child if child and parent desire; encourage parent to talk softly to child and to remain near child’s head.

9. Involve parents in learning specific nonpharmacologic strategies and in assisting child with their use.

10. Educate child about the pain, especially when explanation may lessen anxiety (e.g., that pain may occur after surgery and does not indicate something is wrong); reassure the child that he or she is not responsible for the pain.

11. For long-term pain control, give child a doll, which represents “the patient,” and allow child to do everything to the doll that is done to the child; pain control can be emphasized through the doll by stating, “Dolly feels better after the medicine.”

Specific Strategies

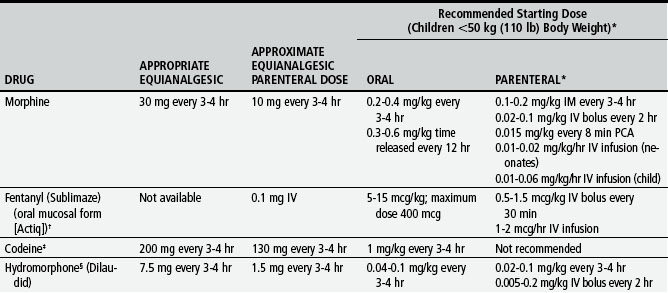

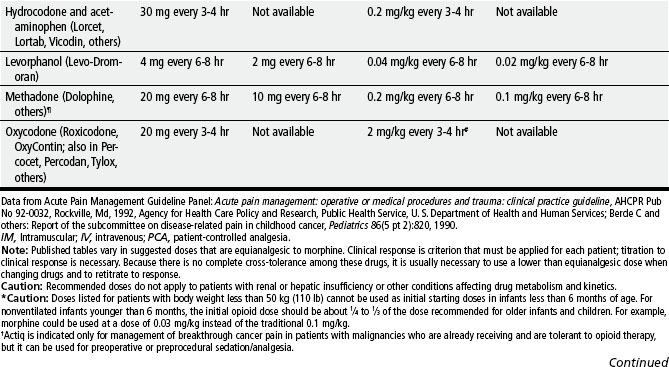

ROUTES AND METHODS OF ANALGESIC DRUG ADMINISTRATION

Oral

1. Oral route preferred because of convenience, cost, and relatively steady blood levels

2. Higher dosages of oral form of opioids required for equivalent parenteral analgesia

3. Peak drug effect occurs after 1 to 2 hours for most analgesics

4. Delay in onset a disadvantage when rapid control of severe pain or of fluctuating pain is desired

Sublingual, Buccal, or Transmucosal

1. Tablet or liquid placed between cheek and gum (buccal) or under tongue (sublingual)

2. Highly desirable because more rapid onset than oral route

3. Produces less first-pass effect through liver than oral route, which normally reduces analgesia from oral opioids (unless sublingual or buccal form is swallowed, which occurs often in children)

4. Few drugs commercially available in this form

5. Many drugs can be compounded into sublingual troche or lozenge.

Intravenous (IV) (Bolus)

1. Preferred for rapid control of severe pain

2. Provides most rapid onset of effect, usually in about 5 minutes

3. Advantage for acute pain, procedural pain, and breakthrough pain

4. Needs to be repeated hourly for continuous pain control

5. Drugs with short half-life (morphine, fentanyl, hydromorphone) preferable to avoid toxic accumulation of drug

Subcutaneous (SC) (Continuous)

1. Used when oral and IV routes not available

2. Provides equivalent blood levels to continuous IV infusion

3. Suggested initial bolus dose to equal 2-hour IV dose; total 24-hour dose usually requires concentrated opioid solution to minimize infused volume; use smallest gauge needle that accommodates infusion rate

Patient-Controlled Analgesia (PCA)

1. Generally refers to self-administration of drugs, regardless of route

2. Typically uses programmable infusion pump (IV, epidural, SC) that permits self-administration of boluses of medication at preset dose and time interval (lockout interval is time between doses)

3. PCA bolus administration often combined with initial bolus and continuous (basal or background) infusion of opioid

4. Optimum lockout interval not known but must be at least as long as time needed for onset of drug

5. Should effectively control pain during movement or procedures

Family-Controlled Analgesia

1. One family member (usually a parent) or other caregiver designated as child’s primary pain manager with responsibility for pressing PCA button

2. Guidelines for selecting a primary pain manager for family-controlled analgesia:

Nurse-Activated Analgesia

1. Child’s primary nurse designated as primary pain manager and is only person who presses PCA button during that nurse’s shift

2. Guidelines for selecting primary pain manager for family-controlled analgesia also applicable to nurse-activated analgesia

3. May be used in addition to a basal rate to treat breakthrough pain with bolus doses; patients assessed every 30 minutes for the need for a bolus dose

4. May be used without a basal rate as a means of maintaining analgesia with around-the-clock bolus doses

Intramuscular

NOTE: Not recommended for pediatric pain control; not current standard of care

1. Painful administration (hated by children)

2. Some drugs can cause tissue and nerve damage.

3. Wide fluctuation in absorption of drug from muscle

4. Faster absorption from deltoid than from gluteal sites

5. Shorter duration and more expensive than oral drugs

6. Time consuming for staff, and unnecessary delay for child

Intradermal

Topical or Transdermal

1. EMLA (eutectic mixture of local anesthetics [lidocaine and prilocaine]) cream and anesthetic disk or LMX4 (4% lidocaine cream)

2. LAT (lidocaine-adrenaline-tetracaine) or tetracainephenylephrine (tetraphen)

4. Transdermal fentanyl (Duragesic)

Regional Nerve Block

1. Use of long-acting local anesthetic (bupivacaine or ropivacaine) injected into nerves to block pain at site

2. Provides prolonged analgesia postoperatively, such as after inguinal herniorrhaphy

3. May be used to provide local anesthesia for surgery, such as dorsal penile nerve block for circumcision or for reduction of fractures

Epidural or Intrathecal

1. Involves catheter placed into epidural, caudal, or intrathecal space for continuous infusion or single or intermittent administration of opioid with or without a long-acting local anesthetic (e.g., bupivacaine, ropivacaine)

2. Analgesia primarily from drug’s direct effect on opioid receptors in spinal cord

3. Respiratory depression rare but may have slow and delayed onset; can be prevented by checking level of sedation and respiratory rate and depth hourly for initial 24 hours and decreasing dose when excessive sedation is detected

4. Nausea, itching, and urinary retention are common doserelated side effects from the epidural opioid.

5. Mild hypotension, urinary retention, and temporary motor or sensory deficits are common unwanted effects of epidural local anesthetic.

6. Catheter for urinary retention inserted during surgery to decrease trauma to child; if inserted when child is awake, anesthetize urethra with lidocaine.

SIDE EFFECTS OF OPIOIDS

Signs of Withdrawal Syndrome in Patients with Physical Dependence

TABLE 2-5 Nonsteroidal Antiinflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs) Approved for Children*

| DRUG | DOSAGE | COMMENTS |

|---|---|---|

| Acetaminophen (Tylenol) | 10-15 mg/kg/dose every 4-6 hours, not to exceed 5 doses in 24 hours or 75 mg/kg/day, orally |

NOTE: Newer formulations of NSAIDs selectively inhibit one of the enzymes of cyclooxygenase (COX-2, which is responsible for pain transmission) but do not inhibit the other (COX-1). Inhibition of COX-1 decreases prostaglandin production, which is necessary for normal organ function. For example, prostaglandins help maintain gastric mucosal blood flow and barrier protection, regulate blood flow to the liver and kidneys, and facilitate platelet aggregation and clot formation. Theoretically, the COX-2 NSAIDs provide similar analgesic and antiinflammatory benefits with fewer gastric and platelet side effects than the nonselective agents. COX-2 NSAIDs are approved for use in patients older than 18 years of age.

* All NSAIDs in this table (except acetaminophen) have significant antiinflammatory, antipyretic, and analgesic actions. Acetaminophen has a weak antiinflammatory action, and its classification as an NSAID is controversial. Patients respond differently to various NSAIDs; therefore changing from one drug to another may be necessary for maximum benefit.

Acetylsalicylic acid (aspirin) is also an NSAID but is not recommended for children because of its possible association with Reye’s syndrome. The NSAIDs in this table have no known association with Reye’s syndrome. However, caution should be exercised in prescribing any salicylate-containing drug (e.g., Trilisate) for children with known or suspected viral infection.

Side effects of ibuprofen, naproxen, and tolmetin include nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, constipation, gastric ulceration, bleeding nephritis, and fluid retention. Acetaminophen and choline magnesium trisalicylate are well tolerated in the gastrointestinal tract and do not interfere with platelet function. NSAIDs (except acetaminophen) should not be given to patients with allergic reactions to salicylates. All NSAIDs should be used cautiously in patients with renal impairment.

Data from Olin BR and others: Drug facts and comparisons, St Louis, 2002, Facts and Comparisons.

TABLE 2-7 Management of Opioid Side Effects

hs. At bedtime; IV, intravenous; PO, by mouth; PR, by rectum; prn, as needed; q, every; tid, three times a day