Section 2 Initial management and education

Clinical presentation of diabetes

Type 1 diabetes

The clinical presentation of type 1 diabetes in younger patients is usually acute with classical osmotic symptoms (Table 2.1).

| Osmotic symptoms | Associated symptoms |

|---|---|

| Thirst | Muscular cramps |

| Polyuria | Blurred vision |

| Nocturia Weight loss Fatigue and lassitude |

Fungal or bacterial infection, usually orogenital and cutaneous, respectively |

Associated symptoms, particularly blurred vision may occur, although these are generally less prominent. Although the islet β-cell destruction of type 1 diabetes is a process that occurs gradually. It is very uncommon to detect type 1 diabetes during the early asymptomatic stages of the condition. Once symptoms appear, diagnosis may sometimes be expedited by awareness of symptoms in other family members with diabetes. Despite the presence of significant osmotic symptoms, patients sometimes do not seek medical advice and may present in DKA (see Table 1.4).

DKA is a life-threatening medical emergency requiring hospitalization. The diagnosis and management of DKA is considered in more detail in Section 4.

Type 2 diabetes

The presenting clinical features of type 2 diabetes (Table 2.2) range from none at all to those associated with the dramatic and life-threatening hyperglycaemic emergency of the hyperosmolar non-ketotic syndrome. In many patients with lesser degrees of hyperglycaemia, symptoms may go unnoticed or unrecognized for many years; such undiagnosed diabetes carries the risk of insidious tissue damage.

| None – asymptomatic patients identified by screening |

| Osmotic symptoms |

Patients with diabetes tend to present in four main ways:

• Classical signs and symptoms – osmotic symptoms plus weight loss

• With macrovascular and/or microvascular complications

• Diabetic decompensation – DKA/HONK (hyperosmolar hyperglycaemic state)

• Routine testing at general practitioner (GP) consultations, medical and surgical clinics/insurance medicals.

History and initial physical examination

Having obtained a detailed history, a physical examination should be undertaken (Table 2.3). The consultation should take place in appropriate and comfortable circumstances.

• The mode of diagnosis and presence of symptoms should be recorded.

• Family history of diabetes should be reviewed.

• For women, enquiry into obstetric (stillbirths, large babies, gestational diabetes) and menstrual history (oligomenorrhoea, especially with features of hyperandrogenism) may be relevant.

• Associated conditions (see Section 1), predisposing and aggravating factors should be identified.

• A detailed history of drug use, smoking habits and alcohol consumption is required along with an enquiry into habitual physical activity and sporting interests.

• Height and weight (plus waist circumference) need to be recorded and body mass index calculated.

• Blood pressure should be measured carefully; lying and standing pressures should be recorded if there is any suggestion of postural hypotension arising from autonomic neuropathy. In diabetes there may be a postural drop with few or no symptoms.

• Evidence of established diabetic complications including neuropathy (including autonomic dysfunction where appropriate) should be sought diligently at diagnosis in patients with type 2 diabetes (see Section 5).

• Unless contraindications exist, notably angle-closure glaucoma, the fundi should be examined through pharmacologically dilated pupils in all patients with type 2 diabetes, as well as in patients with features that are not classical of autoimmune type 1 diabetes.

• Features of other endocrinopathies, signs of marked insulin resistance and specific syndromes of diabetes such as the lipodystrophies are rare.

Table 2.3 Components of the comprehensive diabetes evaluation

BMI, body mass index; CHD, coronary heart disease; DKA, diabetic ketoacidosis; DSME, diabetes self-management education; GFR, glomerular filtration rate; HDL, high density lipoprotein; LDL, low density lipoprotein; MNT, medical nutrition therapy; PAD, peripheral arterial disease.

Source: American Diabetes Association (2011). Reproduced with permission.

Nephropathy

Type 2 diabetes

In addition to early nephropathy, the presence of microalbuminuria may reflect a further increase in risk of macrovascular disease (see p. 199). However, because nephropathy can develop during the asymptomatic phase preceding diagnosis, plasma creatinine should be checked, especially if Albustix-positive (indicative of urinary protein losses of 500 mg/day or more; see p. 200).

Neuropathy and foot disease

Evidence of these complications should be evaluated carefully at diagnosis in patients with type 2 diabetes, as detailed in Section 5.

Screening for diabetes

In the UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS), the severity of diabetes-related tissue damage correlated with the glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) concentration at diagnosis of type 2 diabetes. Thus, there is the prospect that earlier intervention in patients identified by screening of asymptomatic at-risk individuals may prevent or retard chronic diabetic complications. Type 2 diabetes satisfies some of the major criteria for a disorder for which screening would be appropriate. However, there is little evidence to suggest that population screening is cost effective. It is appropriate to screen ’at risk’ groups (see Section 1).

Initial management

Identification of patients with apparently autoimmune diabetes with a relatively slow onset can be problematic; the prevalence of latent autoimmune diabetes in adults (LADA) is not known but is perhaps under diagnosed (see Section 1). The diagnosis is often made retrospectively (glutamic acid dehydrogenase (GAD) + ve, anti-islet cell + ve) following the rapid failure of treatment with oral antidiabetic agents (see Section 3, p. 97). Useful clinical pointers at diagnosis suggesting that insulin may be required include:

• unintentional weight loss preceding diagnosis

• normal body weight or underweight for height at diagnosis

Ketonuria

Autoimmune and non-autoimmune type 1 diabetes

In difficult cases, the presence of serum islet cell, insulin and GAD antibodies may help in the diagnosis of type 1 diabetes (see p. 9). In addition, although relatively uncommon, non-autoimmune forms of type 1 diabetes are recognized, albeit mainly in people from minority ethnic groups.

Pluriglandular syndrome

Antibody positivity does not predict future autoimmune disease with certainty. However, the prevalence of autoimmune thyroid disease, Addison’s disease and other non-endocrine autoimmune disorders such as pernicious anaemia, coeliac disease and premature menopause is increased in patients with type 1 diabetes. Vitiligo is a useful cutaneous marker of autoimmune disease. Periodic checks of target organ function (e.g. thyroid function tests, serum B12 level) are indicated even in the absence of clinical features. Coexisting endocrinopathies may adversely affect metabolic stability (see p. 18).

Influence of comorbidity

Lifestyle management

• perception of their diabetes

• comorbidities that may be related indirectly to their diabetes, such as depression.

Healthy eating

Effective management of diabetes cannot be achieved without an appropriate diet. All patients with newly diagnosed diabetes should receive educational advice from a dietitian as soon as possible after diagnosis (Table 2.4). The initial interview with the dietitian should focus on the patient’s preferences and habits. This should include enquiry about who takes responsibility for cooking at home, whether prepackaged convenience foods form a substantial part of the diet and the amount of food eaten outside the home, for example by the business traveller. Ethnic and social influences are of obvious importance, such as the high saturated fat content of traditional South Asian cuisine or the teenager’s predilection for fast food (Table 2.5).

Table 2.4 Initial dietary advice for newly diagnosed patients with diabetes

Table 2.5 General dietary advice in diabetes

| General guidance on healthy eating should be advised initially |

• Ensure an adequate and balanced nutritional intake

• Aim to provide 50% energy intake from carbohydrate by increasing intakes of complex carbohydrate/fibre-rich foods

• Limit rapidly absorbed carbohydrate intake

• Ensure that complex carbohydrate foods (starchy foods) are eaten at each meal/snack

• Encourage regular eating habits/meals

• Reduce fat intakes to < 30% of energy intake

• Monitor body weight, encouraging weight maintenance and weight reduction when necessary

Nutrition therapy

Individualized and detailed dietary advice requires the input of trained dietitians. However, the general principles that underpin the diet for most diabetic patient differs little in terms of macronutrient composition from the advice that is currently promulgated as a healthy diet for the population in general. Much more relevant to success in an individual patient is a realistic approach bolstered by adequate practical training for the patient (and relatives) and an ability to communicate the objectives effectively and sympathetically. At the outset, simple, easy-to-follow guidelines are appropriate (see Table 2.3).

• Fibre – as for the general population, people with diabetes are encouraged to choose a variety of fibre-containing foods such as legumes, fibre-rich cereals (≥ 5 g fibre per serving), fruits, vegetables and whole-grain products because they provide vitamins, minerals and other substances important for good health.

• Palatability – limited food choices and gastrointestinal side-effects are potential barriers to achieving such high fibre intakes.

• Sweeteners – substantial evidence from clinical studies demonstrates that dietary sucrose does not increase glycaemia more than isocaloric amounts of starch.

Carbohydrate in diabetes management

• A dietary pattern that includes carbohydrate from fruits, vegetables, whole grains, legumes and low-fat milk is encouraged for good health.

• Monitoring carbohydrate, whether by carbohydrate counting, exchanges or experienced-based estimation, remains a key strategy in achieving good glycaemic control.

• The use of glycaemic index and load may provide a modest additional benefit over that observed when total carbohydrate is considered alone.

• Sucrose-containing foods can be substituted for other carbohydrates in the meal plan or, if added to the meal plan, covered with insulin or other glucose-lowering medications. Care should be taken to avoid excess energy intake.

• Sugar alcohols and non-nutritive sweeteners are safe when consumed within the daily intake levels established by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

A number of practices are controversial:

• Unrealistic targets – for some patients the prescription of diets with hopelessly unrealistic targets such as a ‘1000-kcal daily reducing diet’ is a recipe for failure, disillusionment and loss of faith in the dietitian.

• Special foodstuffs – the purchase of products such as cakes aimed specifically at diabetic patients should be discouraged. These are often more expensive, contain calories in the form of sorbitol or fructose, and may cause diarrhoea.

Recommendations

• Dietary interventions that produce a 600-kcal per day deficit result in sustainable modest weight loss. Where VLCD are indicated for rapid weight loss, patients should be under medical supervision.

• When discussing dietary change with patients, health-care professionals should emphasize achievable and sustainable healthy eating.

Encouraging dietary change in clinical practice

Exercise and physical activity

Assessment of physical activity

Smoking

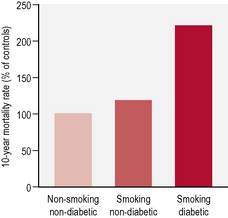

In the general population tobacco smoking is strongly and dose-dependently associated with all cardiovascular events, including coronary heart disease, stroke, peripheral vascular disease and cardiovascular death. In people with diabetes, smoking is an independent risk factor for cardiovascular disease and the excess risk attributed to smoking is more that additive (Table 2.6). Smoking cessation reduces these risks substantially, with the decrease in risk being dependent on the duration of cessation.

| Assessment of smoking status and history |

• All health-care providers should advise individuals with diabetes not to initiate smoking. This advice should be repeated consistently to prevent smoking and other tobacco use among children and adolescents with diabetes under age 21 years.

• Among smokers, cessation counselling must be completed as a routine component of diabetes care.

• Every smoker should be urged to quit in a clear, strong and personalized manner that describes the added risks of smoking and diabetes.

• Every diabetic smoker should be asked if he or she is willing to quit this time.

• If no, initiate brief and motivational discussion regarding need to stop using tobacco, risks of continued use, and encouragement to quit as well as support when ready.

• If yes, assess preference for and initiate either minimal, brief or intensive cessation counselling and offer pharmacological supplements as appropriate.

Source: American Diabetes Association (2011). Reproduced with permission.

Possible ill effects of smoking include:

• decreased insulin sensitivity

• increased mortality (Fig. 2.1)

• independent risk factor for type 2 diabetes

• risk factor for complications – retinopathy, nephropathy, necrobiosis lipoidica and cheiroarthropathy (limited joint mobility).

Alcohol

Alcoholic beverages are a variable and potentially important component of the diet and may have a bearing on a number of aspects of diabetes (Table 2.7). Alcohol provides energy of 7 kcal/g – almost twice that of carbohydrates and approaching the energy value of fats. Calorie load and risk of hypoglycaemia are the principal concerns.

Table 2.7 Potential relevance of excessive alcohol consumption to patients with diabetes

Recommended daily consumption

The recommended maximum daily consumption of alcohol in the UK is:

• Do not substitute alcohol for regular meals or snacks.

• Avoid alcoholic drinks with high sugar content (e.g. sweet wine).

• Avoid lower carbohydrate drinks – they tend to be high in alcohol.

• Avoid alcohol if there is hypertriglyceridaemia, symptomatic neuropathy or refractory hypertension.

• Carry a diabetes identification card in case of emergency.