CHAPTER 2

The chapters in this book are about how policy in the field of health is developed and modified according to problems that arise as society and its values change or as new technology makes necessary reflection about existing values. The authors are interested in tracing the origins of particular health problems and revealing the processes by which they develop and are placed on the policy agenda, and the extent to which they are resolved. What is the problem and how is it being addressed? This might involve examining the institutional structures, the information used in reaching decisions, the values held by the participants and the broader social, economic and political contexts within which policies are formulated. The contributors describe and analyse systematically the actual content of particular health problems and policies.

This chapter begins with an overview of some of the problems frequently encountered in analysing the policy process. These relate to such questions as What is policy? Who is involved? Is policy political? Do models help? and Can policy be rational?

WHAT IS POLICY?

In the media there are references to government policy on a range of topics on a daily basis. We read or hear about how the Australian government is conducting immigration or water resources policy, and of state government reactions to those policies. At other times, the reference is more specific and we read the intricacies of a particular policy, say on the administrative decentralisation of a particular state government’s municipal public health planning, or pressure on the Australian government from state blood banks to change the composition of blood for transfusions by removing white blood cells which could perhaps lead to some groups in the community contracting disease.

The use of the word ‘policy’ is widespread. Political parties have policies on topics ranging from biofuel to how wheat is exported. These might or might not be translated into action when a political party obtains government. They can be dropped from a party’s objectives if the electorate or media are dismissive of a particular policy, such as the Australian Labor Party’s (ALP’s) proposed health ‘gold card’ for all older citizens, not simply for war veterans. In an era in which all nations share a common concern with the consequences of global warming and carbon dioxide emissions, there are calls by scientists and governments for universal policies that transcend narrow national boundaries, as in the report released in February 2007 by the United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. There are policies to be found on the websites of public and private organisations. Most government departments and agencies have officers working in specifically designated units with full-time responsibility for assisting in the development and implementation of policy. In the age of the email and the worldwide web immediate access to a written statement of government policy on almost any topic has become the norm, although governments are sometimes less ready to issue such documents on contentious issues (e.g. abortion). Banks and finance companies have policies on lending to home buyers based on interest rates set by the Reserve Bank and monitored by treasurers, and hospitals have policies for various procedures ranging from patient discharge to the use of expensive new technologies in surgery (see Ch 19).

Governments are expected to be able to articulate their policies on any problem, often at short notice. Government health departments and organisations which collect and disseminate health research findings, such as the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW), are expected to provide health trend data on anything from obesity in children and Type II diabetes to increases in the incidence of chlamydia or hepatitis C infections. Often a ‘snapshot’ of general health in the community is required. The convention of responsible government suggests that the bureaucracy receives policy guidelines or frameworks from the government upon which it is expected to act, but often of course it is the reverse and it is the public servants who develop the strategies and guidelines or frameworks (see Chs 3 & 7). The word ‘policy’ is often used to describe the decisions of government from which a pattern of related decisions, often as regulations derived from Acts of Parliament, is seen to constitute policy. This can be seen in mental health policy (Ch 18), pharmaceutical drugs policy (Ch 17) or environmental health policy (Ch 21).

The system of a political opposition means that government ministers are regularly challenged by their opponents to articulate policies for parliamentary and public scrutiny. Oppositions are similarly involved in defending their alternative policies. The expectation that a government will be able to articulate coherent policy is often dramatically demonstrated in the electronic media. Governments and oppositions often have to defend their own values in relation to health policy changes in sensitive areas, such as the introduction of the abortion drug RU 486 and changes to foetal stem cell research. In both cases, the Prime Minister and opposition party leaders allowed a conscience vote where members vote according to their own principles instead of according to party policy. In the former case, a consortium of women members from the different parties represented in parliament introduced the legislation as a private member’s bill (that is, non-ministerial). In the latter, a former coalition Minister for Health, Senator Kay Patterson, introduced therapeutic cloning legislative changes also as a private member. Both bills were ultimately successful. Given the primacy of the party system in parliaments, successful bills by backbenchers are extremely rare, but this highlights how sensitive health policy can be (see also Ch 13).

WHO IS INVOLVED OR IS POLICY POLITICAL?

That policy is political is usually understood to mean that policy invariably involves competing interests with competing demands. Some analysts (Parsons 1995) who maintain that rationality and effectiveness are too often sacrificed to political expediency regret the intrusion of politics into the policy process. No process associated with conflicting interests can avoid the attempts by the individuals and groups involved to influence outcomes in favour of their own interests. Policy development, implementation and evaluation is therefore essentially a political process.

Federalism and health

This book is concerned with public policy in health, with those policies that have been developed within the wider governmental system. This system includes federal, state, territory and local governments, the public service departments serving them, as well as various semiautonomous public agencies charged with particular responsibilities. Constitutionally, the states and territories are responsible for health, but the federal government does supply most of the money and in reality this means that health is one of the most highly complex areas of policy. The federal system in Australia, which has a federal, or national, government and six state and two territory governments, often with different political parties in power, grafted on to a Westminster system of parliamentary government, allows for many problems of accountability. Despite the development of strategies to enhance ministerial control and increase public service accountability (see McCoppin 1995 and Ch 7), public servants inevitably exercise influence in the policy process by means of their expertise and advice.

There is much ‘buck-passing’ and accusations of blame between the state and the federal governments. A recent report of the parliamentary inquiry into health funding was actually titled The Blame Game (Parliament of Australia 2006). This occurs particularly in areas such as health where everyone has a personal stake in an effective system with, for example, efficient, clean hospitals staffed by expert and friendly staff in sufficient numbers, or expectations of the presence of general practitioners in rural areas. Hospital expenditure and crises of staffing in medicine or nursing are held to be the fault of the states and territories by the federal government, but the states respond that they are insufficiently funded by the federal government and that they need approval for more university places from the federal level (see Chs 4, 6, 9 & 10 for discussions of federal funding and health workforce problems).

Federalism, however, does not remain static. There are subtle changes and shifts in the balance of power quite apart from the few formal changes that have taken place. Generally, the shifts have been towards the federal or national level. In health and healthcare, the trend has been to an increased national, federal policy direction. We can see this as federal strategic policy development in areas such as control over the costs of pathology, control over the costs of general practice, control over the costs of radiology and over the costs of hospitals. There are frameworks for increased accountability and self-regulation through reporting mechanisms and an emphasis on outcome measures. At the level of the states and territories there is local decision making within federal policy guidelines. We can see this demonstrated, for example, in such wide-ranging areas as environmental health, rural health, illicit drugs, food safety policy (Ch 21), palliative care and mental health (Ch 18), all of which have detailed strategy documents.

In the same way that the development of policy is subject to economic and political influences, the process of implementation is constrained by a number of factors. If the policy is national, how can the federal government impose its will on the states and territories, which each have legislative and administrative responsibility for health and healthcare? If the state or territory government has the same political party in power as the federal level, this is more easily achievable, but by no means a fait accompli. State and territory governments have their own constraints, in particular perennial financial problems, which are often attributed to the federal government. State and territory governments, whatever their political persuasion, like to believe that they exercise power in their own right and should, therefore, be able to define their own policy priorities. This means that federal governments must work around these constraints. The Australian Health Care Agreements (formerly Medicare Agreements), which are negotiated every 5 years between the Australian government and the states and territories on federal government funding for public hospitals and related health services, make it attractive for states and territories to pursue particular health policies and unattractive to pursue others. No two states or territories have identical healthcare systems, the differences include variations in the provision of services, in health personnel registration systems (see Chs 6, 9 & 10), in the numbers of members of ethnic communities (see Ch 14) and Indigenous people (Ch 22), in rurality, and so on.

If the policy goals are shared between the federal, state and territory levels, implementation will be pursued more vigorously. There are, however, further implications for uniform national policies. In each state and territory, the relevant public service department, or health agency, or both, might interpret the process of implementation differently. Specific programs developed from the broad policy will be tailored to the specific needs of the community, as seen by the local decision makers. It can be argued that health policy which is informed by research, and which has included the major players in its development, has a greater likelihood of successful implementation, but it is still subject to economic, institutional and political constraints. Interest groups will be active at every stage of the process and their influence will modify initial goals. Australia’s federal system allows two tiers of government for such influence. The policy process is immensely subtle and complex, and while evaluations of health policies and programs will provide a great deal of useful information, they will not illuminate necessarily the whole series of activities and choices which have taken place.

Many areas of policy are not entirely within the control of governments. In terms of health policy this has meant that governments do not solely determine its final shape. In other words, the formation of public policy is the function of both government and of ostensibly private interests and organisations. For example, pharmaceutical corporations (many of which are transnational) can influence policy by their own research and pricing policies. Non-government organisations (NGOs) have recently played a more important role in not only development of health policy and advocacy but also in implementation; for example, Diabetes Australia and the Salvation Army. Voluntary organisations contribute some millions of dollars to the health and welfare sectors, and the private health sector, while it is subsidised by governments, also contributes (Ch 4). In 2004–05 the contribution of all governments to the funding of total health expenditure was 68.2% and of non-government was 31.8% (AIHW 2006a p 22). The federal government basically contributes twice as much as do state governments. The public–private split in healthcare similarly confuses policy. It is, for example, relatively unusual for new developments in surgery to be introduced in the private sector, but Chapter 19 provides a detailed analysis of just such an innovation in cancer surgery. So policy is essentially a political process almost invariably characterised by competing interests. Not surprisingly there are differing views about how such competition is reconciled and which interests prevail.

In some areas of policy, the policy of a national government may be affected by the actions of international agencies due to treaty provisions or the moral authority of such agencies. For example, since Australia is a member of the World Trade Organization, a decision to prohibit certain food imports on quarantine grounds might be challenged by other nations and the decision put before a dispute resolution panel. Dissatisfaction with the actions of Australian governments (both national, state and territory) can sometimes lead to Australian activists approaching United Nations committees, seeking redress for their grievances. Although the findings of such committees cannot be imposed on Australian governments, they sometimes carry significant moral weight.

Swerissen (1998), however, makes a passionate plea for the primacy of political decision making, subject as it is to elections, the media, parliamentary oppositions and the parliament itself. He believes it is a myth to believe that policy decisions are as opaque as the cynics appear to think. Certainly, cynicism is a problem in modern democratic systems. It is important that people are not so cynical that they are turned away from the political system to the extent that they see it as not worth supporting. It is then that what is a fairly fragile system can face its worst threats. Political parties are different, they have different ideologies, and when in government they do different things. The health system is subject to these changing emphases, which often take the form of a focus on the private health system when the Coalition is in power, and a concern for the public system when the ALP is in government (Gardner 1995a).

Political parties and the policy process

Political parties play an essential role in the policy process, a role commonly determined by their relative degree of electoral support and the nature of their parliamentary participation. Parties are at the centre of the Australian system of government, competing for electoral support and, at least in the case of the major parties, seeking to form governments. Ideally, they should offer alternative policy visions, giving voters choices. Parties not in office have an important role in scrutinising and criticising the policies and performance of governments. Parties with smaller electoral support might participate in coalitions or operate in a similar manner to interest groups.

From a policy perspective, political parties often articulate major themes or ideas, leaving the detailed planning for implementation to a later stage in the process. Not surprisingly, parties not in power frequently identify policy problems and proffer solutions. This is often done through such devices as parliamentary question time and through the mass media. Where governments lack a majority in the upper house, or Senate, it is not uncommon for enquiries to be established by opposition parties with the aim of probing policy problems in the formulation and implementation of government policy. Parliamentary enquiries initiated by either of the main party groupings can produce major policy critiques (see above and Ch 18).

The articulation of policy might result from the annual conferences of parties or in the carefully considered process of developing formal platforms, manifestos and policy statements. Often, political parties refrain from publishing details of their policies on particular issues until closer to the time of a general election. Policies are then successively ‘launched’ so as to attract greater public and mass media attention. The larger parties are able to make use of their own ‘think tanks’ for policy development. It should be noted that governments, although usually formed on a majority party basis, are not necessarily bound to follow their previously stated policies. Parties also continually respond to the cut and thrust of political contestation, a process that often leads to policy statements and commitments.

The ideal of parties offering alternative policies in an effort to solve major policy problems is often tempered by the realities of electoral politics. As Gardner has noted:

Political parties are caught in a dilemma. On the one hand, they need to stress the differences between them and argue for their superior policies; on the other, the want to gain the most votes, so there is a need to obscure the differences.

The policies of the major parties on Medicare illustrate this phenomenon. Over the years the fierce hostility of the Liberal Party and National Party towards Medicare, one of the ALP’s principal social policies, was transformed. The Fraser ministry, which came to power in 1975, had actually dismantled Medibank, the ALP’s universal scheme instituted under the Whitlam ministry (1972–75). Upon regaining power in 1983, the ALP reconstituted the scheme as Medicare, a move strenuously opposed by the coalition parties. However, the growing popularity of Medicare among the public and its obvious practical functions led the coalition to reverse its hostility and pledge to retain the scheme if re-elected. The Howard Coalition ministry has retained Medicare but has also effectively sought to encourage higher income earners to opt out of Medicare hospital usage by offering a 30% rebate on private health insurance premiums. The proponents of the policy claimed that pressure on the use of public hospitals would be relieved by patients being able to afford private care. Although the ALP Opposition rejected this as bad policy, the party had little choice but to match the offer at subsequent general elections. In short, both the coalition and the ALP had moved from radical policy alternatives to the centre ground. For some policy analysts this poses a further problem in the policy process since electoral considerations modify the rationality of choices.

POLICY AS PROCESS: ARE MODELS USEFUL?

The theme of policy as process is emphasised throughout this book. Thus policy development is stressed rather than policy making. Policy making suggests that policy is made at one point in time, and that it is made by one authorised source at the top and remains unchanged in implementation and evaluation. Policy development encompasses the full range of processes that are involved. Models can often help to make sense of the processes involved.

Some models try to identify the main stages of the process which suggests a sequential process (see Eagar et al. 2001). The first stage is agenda setting, during which policy issues and problems are identified, defined and discussed. This usually occurs when issues are raised with the authorised decision makers by interest groups. Next policy is formulated. This might involve the creation of new policies or changes to existing ones. Once adopted, policy enters the implementation stage by which it is put into practice. The last stage in the sequential model is that of evaluation, by which the principles and practice of a given policy are monitored, analysed and criticised and an assessment made of the policy’s impact. This stage might, in turn, produce a further round of agenda setting and policy formulation as the results of the evaluation are fed back into the policy process.

In most models the channelling of demands into the political system invariably involves the recognition of that system to make authoritative decisions. Those making the demands also give their support to the political system by acknowledging its authority to adjudicate between competing demands and to make binding decisions. In Easton’s (1965) model, demands and supports constitute inputs into the system. The decisions and policies that are made within the authoritative centre constitute the outputs of the political system. These might take the form of decisions to favour one group against another, to increase or decrease the allocation of resources or to accept particular values by which to conduct policy. Policy development as a system of inputs, outputs and feedback leading to different inputs and outputs appears too rational and systematic for exponents of the model of limited or bounded rationality (Lindblom 1959, Parsons 1995, Simon 1976). Robbins (1989) discusses the satisficing model where decision makers reduce complex problems to what can be understood and assimilated while removing their complexity.

In this model, policy results from a largely unplanned process, which responds to circumstances by means of adjustments to existing policy in an incremental way. Either ends or means can be unclear, requiring political judgment. It is referred to as ‘disjointed incrementalism’, in contrast to the ‘rational comprehensive’ model which portrays policy as the result of a rational process of comprehensively analysing all available data prior to making an informed decision among options. It is perhaps too simplistic and thus of limited use in decision making. Further, the ‘limited rationality’ of those making the decisions means that it is impossible to take all relevant factors into account, and there can be unintended consequences of many pieces of seemingly rational policy.

PLURALISM AND HEALTH

The pluralist perspective of the policy process sees interest groups competing with each other to achieve their desired outcomes. Policy cannot by definition be rational from this perspective. while the resources of these groups vary, including power, no single group is able to act autonomously. Any group that is able to organise with the aim of influencing policy outcomes has the potential to exercise some degree of political power. Governments are receptive to various interests and no one group prevails on every issue. In the health field, for example, the pluralist view would not accept that the medical profession is dominant in the policy process. Rather, while conceding that the medical profession undoubtedly possesses resources which give it power, pluralists would argue that there are other professions or groups, for example, the allied health professions or consumer and advocacy groups, which also exercise a degree of power in the policy process and that no one elite dominates. It is difficult to argue, however, that these groups exercise countervailing power to the medical profession.

Nevertheless, the autonomy of the medical profession is curtailed to a large degree by the government, particularly, in terms of resources and regulation of technology, pharmaceuticals and practice, in part through the Professional Services Review, an independent authority established by legislation to ascertain whether a practitioner has practiced inappropriately and to maintain the integrity of the Medicare Benefits Schedule (MBS) and the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS) (Professional Services Review 2006). The Australian government provided 76.8% of the funding for medical services in 2003–04 (AIHW 2006b p 305). In Chapter 4, the increasing importance of evidence-based medicine and evidence-based health policy and its application to decisions on health sector funding are discussed. Much consideration of policy is based on the notion that people know what their interests are and articulate these interests within the political system through such devices as the mass media, representations to political representatives, demonstrations or industrial action. These demands are aggregated through the medium of political parties or interest groups. Often these demands show conflicting interests among different groups. There are also aspects of the policy process that are hidden. A decision to do nothing can be a policy output. The power of non-decision making is by definition the most difficult to research, but it is consistent with models of political systems which see all of the important decisions for society being made by elites. This is where the status quo is often maintained, or some innovation is not pursued, because of the problem of upsetting particularly powerful groups, even if they are not directly consulted. In the health sector this might mean the medical profession, or medical monopolists in Alford’s term (1975), with their supporters in the government itself and in government departments.

STRUCTURAL INTERESTS AND HEALTH

A way of examining why some groups exercise political power is to examine the structures of society. The interests of some groups are furthered by the structures of society while the same structures repress the interests of some groups. Using a structural interests approach, Duckett (1984), following Alford (1975), has identified the three principal structural interests in health in Australia as professional monopolists, corporate rationalists and equal health advocates. The dominant interest, the professional monopolists, who are made up mostly of medical practitioners but also include members of other health professions, seek a controlling influence in health policy. The corporate rationalists challenge them. These are the bureaucrats in large health institutions and in the federal, state and territory health departments who emphasise rational planning and efficiency ahead of deference to the traditional social status and special expertise of health professionals. The equal health advocates represent repressed structural interests such as lower socioeconomic or community groups (see also Gardner 1995b). In other words, they have a focus on consumer advocacy and are concerned with community participation and accountability.

The complexity of health policy and its importance to the Australian Medical Association (AMA) representing the medical profession can be seen by the prominence given in its national publication to the ALP’s ‘new health team’ in 2007 after Kevin Rudd was elected leader (AMA 2007). Not only are there no fewer than eight ministers in the new shadow ministry who are either directly linked to health or are in related portfolios, but they are also each pictured in colour and with an article detailing their responsibilities. The AMA knows that it has to work with the current government and also with the opposition, which has the potential to be elected at the next election. Interestingly, the power of the AMA was recognised in a survey in 2006 of federal politicians where it came out as the best lobby group in Australia – ahead of the Chamber of Commerce and Industry, the Australian Industry Group and the National Farmers’ Federation (AMA 2007).

NEW PUBLIC SECTOR MANAGEMENT

Before moving on to whether policy can be rational when it is situated within what has been described as a ‘strife of interests’ (Sax 1984), it is perhaps useful to look at changes in public sector management that attempt to bring coherence to the process. These changes have been adopted internationally in, for example, the United States (US) and the United Kingdom (UK) and in Australia. The principles have been adopted by governments from either of the main parties (Labor or Liberal National) in Australia since the 1980s and are not likely to disappear, so entrenched have they become. What in Australia has mainly been referred to as economic rationalism, or managerialism, has become so accepted as to be almost a received wisdom. It arose in the US and UK under conservative governments and was part of a larger set of principles about how economies should be organised, usually referred to as neo-liberalism, and embodying market or pseudo-market notions of freedom of competition. The principles of competition are translated into corporate management so that there is an apparent freedom of decision making but within broad strategic policy guidelines incorporating strict reporting mechanisms. There are incentives and disincentives for those acting in the various policy areas to behave in a certain way.

The organising principles in the health sector in the preceding 20 years reflect elements of economic rationalism, although new public sector management has now largely replaced these terms. Hancock’s book, Health policy in the market state (1999) provides a thorough analysis, but we shall have to be content here with some of the important characteristics (see Box 2.1). While providing an emphasis on accountability and efficiency so that costs are cut in a context always of scarcity of resources, there is also a focus on effectiveness in the delivery of health and healthcare (see also Ch 7). The overall guiding principle is that of policy decisions and problems being addressed on the basis of data; the so-called notion of being data driven, but can health be so entirely rational given the sacredness of human life and other important values?

BOX 2.1 CHARACTERISTICS OF NEW PUBLIC SECTOR MANAGEMENT

- Meta-policy and planning with associated strategic guidelines and frameworks.

- Incentives and disincentives at every level.

- Emphasis on outcomes.

- Emphasis on products.

- Centralisation of control.

- Separation of purchaser (or funder) and provider with user-pays component.

- Devolution of responsibility and tactical decision making.

- Accountability, quality assurance, customer focus and staff appraisal.

- Data driven and evidence based.

- Contracting out or outsourcing.

- Incentives and disincentives at every level.

CAN POLICY BE RATIONAL?

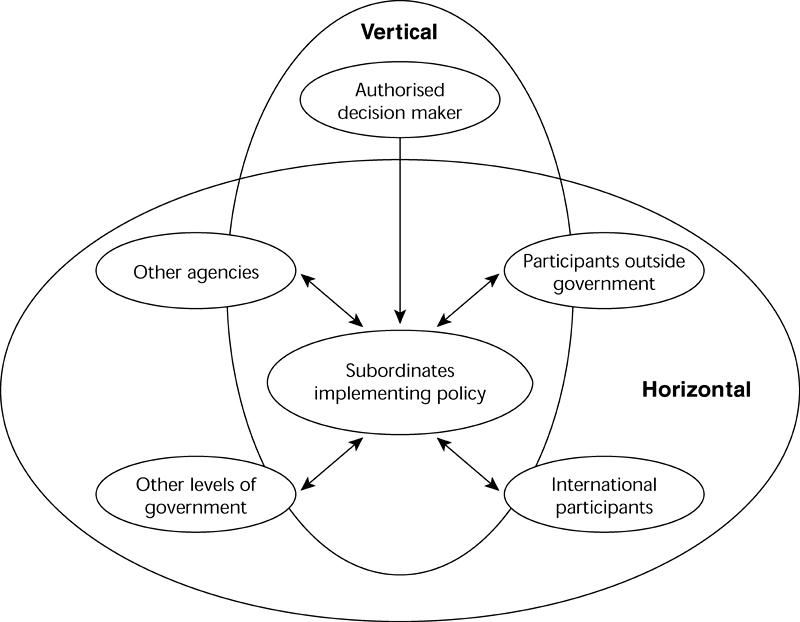

Although Colebatch (2002) uses similar language to Easton, his model is perhaps closer to the actual process of policy formulation by being less linear. His authorised decision makers are in the vertical dimension of legitimate government authority ‘which stresses instrumental action’ and rational choice, and includes not only the decisions, but also their implementation and future compliance with those. The model’s horizontal dimension is concerned with ‘relationships among policy participants in different organisations’ (Colebatch 2002 p 23) and between organisations. These organisations and participants in the policy process are outside the vertical dimension of authorised decision making, but not separated from it.

The beauty of Colebatch’s model (Fig 2.1) (Colebatch 2002 p 24) is that it allows for the inclusion of other levels of government as in a federal system where there is a national or central government with state, territory and local governments. The application of the model could show how important in recent health policy negotiations in Australia are organisations which connect federal, state and territory government health ministers and senior health bureaucrats on a regular basis as in the Australian Health Ministers’ Advisory Council, the Housing Ministers Advisory Council, the Council of Australian Governments (COAG) and associated or similar bodies. Moreover, most policy decisions produce effects that require further policy adjustment. In Australia, as we have seen, where the state and territory governments are responsible for health but the federal government provides most funding for services and for health research, and is therefore extremely influential in health policy, authorised decisions are the result of protracted negotiation with those in the horizontal dimension leading to a sometimes awkward consensus, and to many rational policies falling between the cracks. For example, the federal government and the states and territories had, at the beginning of 2007, still failed to agree on nationally consistent assessment standards for overseas trained medical practitioners, even after the case of Dr Patel in Queensland (Ch 14), but COAG might ultimately prevail.

Figure 2.1 The vertical and horizontal dimensions of policy. Source: Colebatch 2002 Policy, 2nd edn, p 24. Reproduced with the kind permission of the Open University Press Publishing Company

The model can also be transposed to the state and territory level where the state or territory, rather than the federal government, would be in the vertical dimension, while in the federal government model the state and territory governments are in the horizontal level. For a detailed discussion of health policy development and implementation and the negotiation of agreements within and between different governmental structures see particularly Chapters 3, 6, 7 and 8. For interactions between the states and the federal system in mental health policy see Chapter 18. The importance of Colebatch’s model lies in being able to accommodate many participants in the process of the construction of health policy at any level. The number of specialised interest groups involved in the health field and the constant competition for increasingly scarce resources demonstrate the complexity of the policy process in the area of health.

While there are obvious deficiencies in policy models, this does not preclude policy planners from attempts to bring a more logical, ordered approach to social or health problems in which objectives and costs are identified and options are canvassed. Palmer and Short (2000) suggest that while health policy analysis is different from analysis of other policy areas because of three critical factors – the unique role of the medical profession, the complexity of healthcare, and community expectations linked to health – this should not mean that the policy literature is ignored.

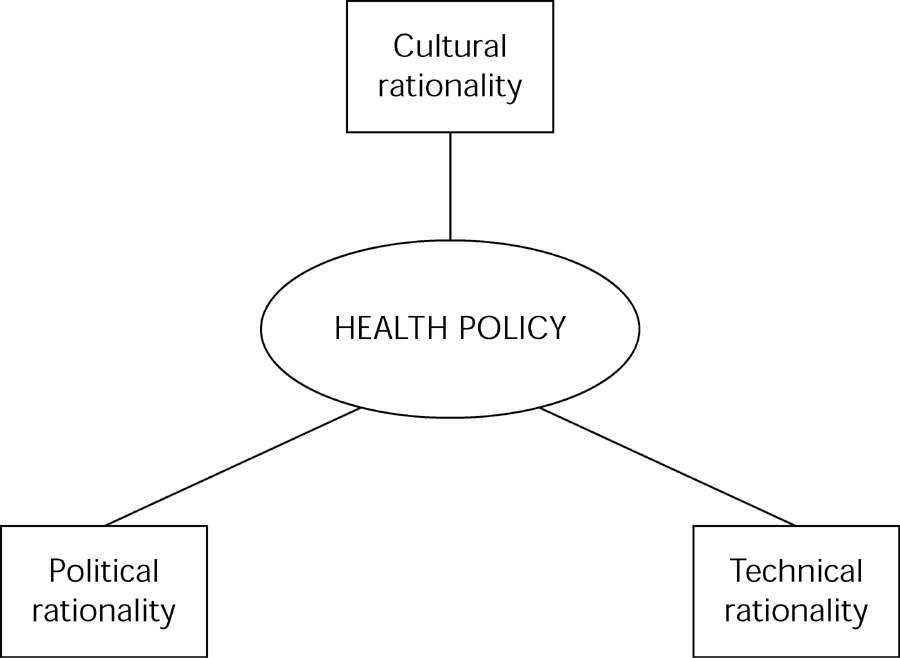

Eagar et al. (2001) argue throughout their book on health planning that a rational comprehensive model of planning, implementation and evaluation is impossible. Even though it will have elements of rationality it is unpredictable from the political, social, cultural and economic forces that impinge on it (see also Ch 10 on alternative therapies). In some senses, this is because medicine and other health-related areas in common with policy share a component that can override rationality, or what appears to be rational. Judgment is required in both spheres as decisions are not always clear-cut because there are different results from research and different interpretations of research. Not only this, but, as we have seen above, there are also many considerations and participants that come into play. Lin (2003) proposes a model of competing rationalities for this seeming paradox, which nicely sums up the problems that have been outlined and discussed above, and which appear in the following chapters.

The competing rationalities are cultural, political and technical (Lin 2003 pp 13–16). Cultural rationalities are about values and ethics, including the value placed on health and quality of life. Section 3 of this book examines some of these cultural rationalities in depth (see for example Chs 13 & 14). Political rationality includes those who contribute to policy decisions, such as interest groups, and therefore depends, like pluralism, on an open and transparent society; one which is open to influence, and so makes legitimate authorised decision making. Power is transformed into authority by reason of consent. It is about means and ends and the context and consequences of policy. The previous discussion in this chapter of the political nature of policy suggests how these political rationalities might play out.

Technical rationality is about research. It is about evidence and universality, and requires ‘reliable epidemiological, economic and administrative information systems’ (Lin 2003 p 15). Another important feature is the need for ‘effective communication between health professionals, researchers and policy makers’ and this might not be present (Lin p 15). Figure 2.2 shows the competing rationalities that are continually contested at any one point in time and that bear the burdens of the past and the various versions of a future, which each one brings to it. The analyses in Sections 3 and 4 in this book tend to support Lin’s argument that ‘Australian health policy is dominated by political rationality, which occasionally reflects cultural rationality’ (pp 15–16).

Figure 2.2 Health policy as a set of competing rationalities. Source: Lin 2003 Fig 1.1 p 14

CONCLUSION

Conceptual frameworks which provide ways of understanding how the policy process might work, and which seek to explain the distribution of power, have been explored. Common difficulties in the study of policy have been identified, but the purpose of this book is to encourage further analysis of health policy and problems. The chapters that follow contribute to the literature on health policy by providing analytical insights into a variety of contemporary health policies and the importance of structure, values, and changing trends giving rise to either emerging or perennial problems in the health sphere. These are not necessarily distinct or separate. For example, changes in technology which mean that life can be extended by artificial means create enormously contested areas for those with the responsibility for decisions (Ch 13). Most of all the health policy process is not neat and ordered; it is complex and disjointed, dependent on context, institutions and organised values. It is the result perhaps of the particular social, economic and political context at any one point in time. Nevertheless, if only because of limited resources and an ageing population with a concomitant pressure on expenditure and a reduction in the working age population to provide government income (Ch 16), there is little doubt that health policy will increasingly be based on the rational analysis of health data (see Chs 4 & 11) and a focus on illness prevention as well as illness treatment.