CHAPTER 2

Cervical Facet Arthropathy

Definition

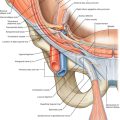

Cervical facet joints are located in the posterior portion of the cervical spine (Fig. 2.1). These paired synovial joints allow mobility and provide stability to the head and neck. Each of these joints is innervated by the medial branch of the posterior primary ramus [1–3]. Cervical facet arthropathy refers to any acquired, degenerative, or traumatic process that affects the normal function of the facet joints in the cervical region, often resulting in a source of neck pain and cervicogenic headaches. It may be a primary source of pain (e.g., after a whiplash injury) but often is secondary to a degenerative or injured cervical disc, fracture, or ligamentous injury. Common causes of cervical facet pain include acceleration-deceleration cervical injuries (whiplash), a sudden torque motion to the head and neck with extension and rotation, and a cervical compression force. In some cases, simply looking upward may cause facet pain. The cervical facet joints may also become painful in conjunction with a cervical disc herniation, after a cervical discectomy or fusion, or after a cervical compression fracture.

Cervical facet arthrosis appears to increase with age and occurs more commonly in the upper cervical spine. In cadaveric studies, the prevalence of cervical arthrosis was greatest for the C4-C5 level, followed by the C3-C4 level [4]. The C6-C7 level was least involved. Abnormal findings within the cervical facet joints appear to be independent of race and gender [5].

Symptoms

Patients typically complain of generalized posterior neck and suboccipital pain but may present with localized tenderness over the posterolateral aspect of the neck. Pain provoked with cervical extension and axial rotation is common. These joints may refer pain anywhere from the midthoracic spine to the cranium and often in the suboccipital region [6–8]. Neurologic symptoms, such as sensory complaints and muscle weakness in the upper limbs, are not expected in patients with primary cervical facet pain. Concomitant nerve root or cord injury is more likely if these symptoms are present.

Physical Examination

The essential element of the examination is manual palpation of the spinal segments and elicitation of reproducible pain over the involved joints [9]. Localized point tenderness over the cervical paraspinal muscles is common and is precipitated by excessive cervical lordosis, causing abnormal joint forces. The fluidity of motion of the involved spinal area–cervical region may suggest extension pain with relief on flexion. Patients may present with loss of cervical motion and paraspinal spasms. Unless cervical disc or nerve root disease is also present, the findings of the neurologic examination are otherwise typically normal.

Functional Limitations

Cervical extension and rotation, overhead lifting, and overhead reaching may be difficult when the cervical spine is involved. This may interfere with activities such as bathing, grooming, and driving.

Diagnostic Studies

Fluoroscopically guided intra-articular arthrography confirmed that anesthetic injections are the “gold standard” for diagnosis (Fig. 2.2) [10–13]. Abnormalities detected on radiography, computed tomography, or magnetic resonance imaging have not been shown to correlate with facet joint pain. A single-photon emission computed tomographic scan can be used in refractory cases of suspected cervical facet disorders to rule out underlying bone processes that may mimic facet pain (e.g., spondylolysis, infection, tumor) [14]. When an abnormality is detected, the scan may confirm the proposed diagnosis and determine which specific joint is affected.

Treatment

Initial

Initial treatment emphasizes local pain control with ice, stretching, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and oral analgesics, topical creams, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation, local periarticular corticosteroid injections, and avoidance of exacerbating activities [15]. Specialized pillows may be helpful, but rarely are cervical collars indicated.

Rehabilitation

Manual forms of therapy (e.g., myofascial release, muscle energy, soft tissue mobilization, and strain-counterstrain techniques) and low-velocity manipulations (e.g., osteopathic manipulation) are commonly used for isolated facet disorders, but their effectiveness has been questioned [16,17]. In healthy patients with no associated spinal disease (e.g., disc abnormalities, stenosis, radiculopathy, fracture), low-velocity manipulations may be used on a limited basis in cases unresponsive to routine conservative care [18–20]. Use in the cervical region should be approached with extreme caution and performed only by experienced practitioners.

Physical therapy may consist of passive modalities such as electrical stimulation, ultrasound, and traction to reduce local pain. However, these modalities have not been shown to change long-term outcomes [18–21]. Regional manual therapy with facet gapping techniques can be helpful. Advancement into a flexion-biased exercise program with regional stretching is the mainstay of rehabilitation. Cervical exercises include both static and dynamic resisted forward and lateral flexion movements. Following cervical facet injections, passive modalities, stretching, and exercises can be useful to reduce pain and to maximize functional recovery. For recurrent episodes of pain, a change in daily and work activity or in sporting technique and other biomechanical adjustments may eliminate the underlying forces at the joint level.

Procedures

Intra-articular, fluoroscopically guided, contrast-enhanced facet injections are considered critical for proper diagnosis and can be instrumental in the treatment of facet joint arthropathies [22,23]. Ultrasound guidance for facet injections is gaining in popularity [24,25]. A patient can be examined both before and after injection to determine what portion of his or her pain can be attributed to the joints injected. Typically, small amounts of anesthetic or corticosteroid are injected directly into the joint. Another step may be to perform medial branch blocks of the affected joints with small volumes (0.1 to 0.3 mL) of anesthetic. If the facet joint is found to be the putative source of pain, a denervation procedure by use of radiofrequency, cryotherapy, or chemicals (e.g., phenol) may be considered [26,27]. Acupuncture may also be considered [28].

Surgery

Surgery is rarely necessary in isolated facet joint arthropathies. Surgical spinal fusion may be performed for discogenic pain, which may affect secondary cases of facet joint arthropathies.

Potential Disease Complications

Because facet joint arthropathy is usually degenerative in nature, this disorder is often progressive, resulting in chronic, intractable spinal pain. It usually coexists with spinal disc abnormalities, further leading to chronic pain. This subsequently results in diminished spinal motion, weakness, and loss of flexibility.

Potential Treatment Complications

Treatment-related complications may be caused by medications; analgesics may cause constipation or liver dysfunction, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs may cause gastrointestinal and renal problems. Local periarticular injections and acupuncture may cause local transient needle pain. Facet injections may cause transient local spinal pain, swelling, and possibly bruising. More serious injection complications may include infection, injury to a blood vessel or nerve, injury to the spinal cord, and allergic reaction to the medications [13]. Fortunately, major complications are rare [29]. Exacerbation of symptoms often transiently occurs after injection. Cervical injections may also precipitate headaches.