Case 2 Anxiety

Description of anxiety

Definition

Anxiety is an unpleasant and often distressing sense of uneasiness, apprehension and/or nervousness. Anxiety is considered to be a standalone, non-pathological symptom (i.e. a normal response to an environmental stessor such as workplace or examination stress), as well as a central feature of ‘anxiety disorder’, a term that is inclusive of generalised anxiety disorder (GAD), phobias, panic disorder, obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD) and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).1

Epidemiology

The lifetime prevalence rate of GAD ranges from 10.6 per cent to 16.6 per cent. This disorder is most prevalent in women, and appears to increase with advancing age. For the more specific anxiety disorders, the lifetime prevalence rates range from 0.5–1.3 per cent for OCD, 1.0–1.2 per cent for panic disorder, 1.2–2.1 per cent for PTSD, 3.6–5.3 per cent for phobias and 2.6–6.2 per cent for GAD.2

Aetiology and pathophysiology

Anxiety disorders are complex conditions that appear to originate from a number of causes. Genetic predisposition and/or familial history, for instance, have been associated with panic disorder, GAD, phobias and OCD.3 Physiological factors, including group A beta-hemolytic Streptococcus infection and trauma or postpartum events are, respectively, also implicated in OCD and panic disorder. But most attention has focused on the neurochemical aetiology of these disorders. Elevated central nervous system catecholamine levels (e.g. panic disorder), impaired gamma-amino butyric acid metabolism (e.g. panic disorder), carbon dioxide sensitivity (e.g. panic disorder), abnormal serotoninergic and noradrenergic activity (e.g. GAD and PTSD), reduced dopamine (D2) receptor and transporter binding (e.g. phobias), abnormal number and/or function of serotinergic receptors (e.g. OCD), neurological disease (e.g. OCD), increased limbic system activity (e.g. PTSD), impaired lactate metabolism (e.g. panic disorder), and basal ganglia dysfunction and prefrontal hyperactivity (e.g. OCD) are just some of the many neurochemical causes of these disorders.4

The pathogenesis of anxiety disorders is only partly explained by these physiological elements. The development of these conditions is also influenced by socioenvironmental factors such as stress, illicit drug use (e.g. marijuana and lysergic acid diethylamide, or LSD), diet (e.g. caffeine), poor social support (e.g. PTSD) and the demise of close relationships (e.g. panic disorder). Behavioural elements also may be implicated in the pathogenesis of anxiety disorder, including the development of abnormal or irrational conditioned responses to fearful situations (e.g. panic disorder), life events (e.g. GAD) or stressful situations (e.g. OCD).4,5

Clinical manifestations

Anxiety is an elusive symptom that can manifest in any person, at any time, in any given situation and to any degree. Anxiety can manifest in any health condition and the physiological features of anxiety can mimic other disorders. As a result, distinguishing anxiety from other medical conditions may be a challenge for some clinicians. A critical first step to identifying anxiety disorder is to understand that anxiety is only one symptom of this condition. Other symptoms that commonly manifest in this group of disorders are irritability, poor concentration, insomnia, restlessness, muscle tension, avoidance behaviour, preoccupation with an event or situation, easy fatigability, tachycardia, palpitations, shortness of breath and an exaggerated startle response.1,3,4

The duration of anxiety is also important. Panic disorder, for instance, is an acute condition that manifests rapidly and peaks within 10 minutes. PTSD can be acute (i.e. occurring soon after an event) and chronic (i.e. occurring more than 3 months after an event). Conditions such as GAD, OCD and phobias are chronic and can exist for many months, years or decades. While the intensity of symptoms is often most severe in acute panic disorder, the severity of symptoms in other anxiety disorders varies greatly.1,3,4

Clinical case

33-year-old woman with generalised anxiety disorder

Rapport

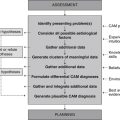

Adopt the practitioner strategies and behaviours highlighted in Table 2.1 (chapter 2) to improve client trust, communication and rapport, and to assure the accuracy and comprehensiveness of the clinical assessment.

Medical history

Family history

Mother has depression, father has type 2 diabetes mellitus, paternal grandmother has agoraphobia.

Lifestyle history

Illicit drug use

| Diet and fluid intake | |

|---|---|

| Breakfast | Cornflakes® cereal with skim milk, coffee. |

| Morning tea | Coffee. |

| Lunch | Wholemeal sandwich with tomato, low fat cheese, lettuce and/or ham. |

| Afternoon tea | Coffee, sweet biscuits. |

| Dinner | Lamb and vegetable curry, fish in coconut cream, baked cod with tomato and onion, beef meatballs with sweet potato bake. |

| Fluid intake | 4–5 cups of percolated coffee a day, 1–2 cups of water a day. |

| Food frequency | |

| Fruit | 1 serve daily |

| Vegetables | 2–3 serves daily |

| Dairy | 2 serves daily |

| Cereals | 5 serves daily |

| Red meat | 1 serve a week |

| Chicken | 1 serve a week |

| Fish | 3 serves a week |

| Takeaway/fast food | 1 time a week |

Physical examination

Inspection

The client is cooperative, well groomed, appropriately dressed and maintains good attention and eye contact. Gait and posture are normal. Skin is dark brown in colour with no abnormal pigmentary signs. Nails are strong and intact. There is no evidence of goitre, proptosis, tremors or virilisation.

Diagnosis

Anxiety (actual), related to emotional stress (anxiety symptoms heighten when husband is away and when work responsibilities increase; anxiety is alleviated when client is not at work), life-changing event (anxiety symptoms emerged around the time the client moved to Australia), poor social support (client’s family is overseas, and husband is frequently away for work – limited access to these social supports may predispose the client to anxiety), and/or excess caffeine intake (high caffeine intake may cause anxiety symptoms in susceptible individuals – the client consumes 4–5 cups of percolated coffee a day, which is equivalent to approximately 360–450 mg of caffeine daily).

Planning

Expected outcomes

Based on the degree of improvement reported in clinical studies that have used CAM interventions for the management of anxiety,6–8 the following are anticipated.

Application

Diet

Low-fat, Mediterranean and/or low-sodium diets (Level II, Strength C, Direction o)

Several studies have examined the effect of diet on psychological function, but there is no convincing evidence that diet, including low-fat, Mediterranean and low-sodium diets, are any more effective than controls or standard diet at improving anxiety or psychological wellbeing.9–11 Thus, rather than prescribe a particular type of diet for this client, it may be more pertinent to increase dietary consumption of foods and nutrients that demonstrate anxiolytic activity (see ‘Nutritional supplementation’ below for specific examples).

Lifestyle

Physical exercise (Level I, Strength A, Direction +)

Increasing levels of physical activity are associated with improvements in physiological and psychological health and wellbeing.12 According to findings from a meta-analysis of 49 RCTs, exercise therapy also demonstrates moderate reductions in anxiety when compared to no-exercise controls or other anxiolytic treatment.13 The anxiolytic effect of exercise appears to be less significant in children and adolescents.14

Relaxation therapy (Level I, Strength A, Direction +)

Relaxation therapy describes a range of mind–body techniques that induce the relaxation response and attenuate sympathetic nervous system activity. Many studies have explored the effectiveness of relaxation therapy in anxiety, including 19 RCTs. A meta-analysis of these RCTs found relaxation therapy to be effective at reducing anxiety, particularly state and trait anxiety, with meditation found to be superior to progressive relaxation, autogenic training and multimethod approaches.6 These findings were consistent across studies, although the significant heterogeneity of these trials, including the various types of anxiety and the range of treatment approaches used, suggests results should be interpreted with caution.

Tai chi (Level II, Strength C, Direction +)

Tai chi is an ancient Chinese therapy often used as a meditative technique, soft martial art or form of physical exercise. It is not surprising, then, that the physical and psychological benefits of tai chi are similar to exercise.15,16 In terms of psychological effects, evidence from a number of RCTs suggests that tai chi is superior to sedentary controls in reducing anxiety,15–17 but given that studies are small and methodologically different, further research is needed before any firm conclusions can be made.

Yoga (Level I, Strength C, Direction +)

Yoga is an ancient Indian practice that integrates stretching, exercise, posture and breathing with meditation. Given that these techniques are likely to induce a relaxation response, yoga may be helpful in alleviating emotional stress and anxiety. Findings from a systematic review of eight controlled clinical trials (including six RCTs)18 and results from four recent trials19–22 show that yoga brings about positive improvements in various types of anxiety, including OCD, phobia, anxiety neurosis, psychoneurosis and examination anxiety. Given the high risk of bias attributed to inadequate randomisation, high rates of attrition and uncertainty about allocation concealment or blinding, these findings should be interpreted with caution.

Nutritional supplementation

5-hydroxytryptophan (5-HTP) (Level II, Strength C, Direction +)

The amino acid 5-HTP is a metabolite of tryptophan and a precursor of the neurotransmitter serotonin. Because serotonin plays a key role in the pathogenesis of anxiety, it is postulated that 5-HTP supplementation may increase brain serotonin production and release, and subsequently elevate mood. Few high-level studies have explored this hypothesis, however. In one RCT, 5-HTP supplementation (200 mg single dose) was found to be significantly more effective than placebo at reducing anxiety levels (i.e. panic symptom list score, visual analogue scale of anxiety, number of panic attacks) in 24 patients with agoraphobia (p = 0.012), but not in 24 healthy volunteers.23 Another RCT, which looked at the effect of 5-HTP supplementation (variable dose for 8 weeks) in 45 participants with anxiety disorder, found 5-HTP to be as effective as clomipramine and more effective than placebo at reducing state trait anxiety, yet less effective than clomipramine and as effective as placebo at reducing HAM-A scores.24 Even though 5-HTP shows promise as an anxiolytic agent, the small size of these studies limits the generalisability of these results.

Inositol (Level II, Strength B, Direction + (for panic disorder only)

Inositol is a B-complex vitamin that serves as a second-messenger precursor. Given that the phosphatidyl-inositol second messenger system is linked to serotonin and noradrenalin receptor subtypes,25 inositol may be useful in the treatment of anxiety disorder. As a treatment for panic disorder, two RCTs found inositol 12–18 g daily for 4 weeks to be superior to fluvoxamine (p = 0.049)26 and statistically significantly superior to placebo (p = 0.03)25 in reducing the number of panic attacks. As a treatment for OCD, inositol (18 g daily for 6 weeks) was found to be no more effective than placebo at reducing anxiety or OCD severity under RCT conditions. It is probable that this small study (n = 10) did not have sufficient power to detect a significant difference between groups, which suggests that evidence from larger studies is needed.

Melatonin (Level II, Strength B, Direction +)

Melatonin is a hormone secreted by the pineal gland. The hormone is responsible for regulating the body’s sleep–wake cycle and, as such, may play a part in promoting sedation, as well as reducing anxiety. Many studies have explored the effectiveness of melatonin in short-term anxiety, specifically, preoperative anxiety. While most of these studies show melatonin to be superior to placebo, and as effective as conventional anxiolytics in reducing preoperative anxiety,27–32 little is known about the effectiveness of melatonin in chronic anxiety disorder.

Multivitamins (Level II, Strength C, Direction o)

Nutrient deficiencies can lead to a number of psychological manifestations. It seems logical, therefore, that these symptoms might improve with micronutrient supplementation. According to one double-blind RCT of 80 healthy male volunteers, this appears to be the case. The trial found multivitamin and/or mineral supplementation for 28 days significantly reduced anxiety levels and perceived stress when compared to placebo.33 In an RCT of 59 older people, micronutrient supplementation was found to be inferior to placebo at 8 weeks.34 These conflicting results suggest further research is needed in this area.

Omega 3 fatty acids (Level II, Strength B, Direction +)

The essential fatty acids, eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), are purported to produce psychotropic effects.35 A small double-blind RCT adds support to this claim: the administration of omega 3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (3 g) for 12 weeks in 21 substance abusers significantly reduced anger and anxiety scores when compared to soybean oil control.36 This is consistent with findings from an earlier controlled trial of healthy subjects with test anxiety.37 The effectiveness of omega 3 fatty acid supplementation in GAD is not yet known.

Selenium (Level II, Strength B, Direction o)

Selenium, an essential trace element, is responsible for a number of structural and enzymatic functions within the body. Not surprisingly, a deficiency in selenium may lead to a wide range of adverse effects, including hostility, confusion, depression and anxiety.38 This has led many researchers to investigate the effect of supplemental selenium on mood. In one double-blind crossover RCT (n = 50), participants treated with 100 μg selenium daily for 5 weeks demonstrated, using the profile of moods states (POMS) tool, a significant reduction in anxiety when compared to patients receiving placebo.39 In another RCT, HIV+ drug users (n = 63) administered 200 μg selenium daily for 12 months demonstrated a marginally significant reduction in state anxiety and a statistically significant reduction in trait anxiety when compared to placebo-treated individuals.40 A more recent and much larger RCT (n = 448) found no statistically significant difference in POMS-bipolar form scores between placebo and selenium (100, 200 and 300 μg) groups after 6 months.41 Evidence of the effectiveness of selenium in anxiety is therefore inconclusive.

Herbal medicine

Bacopa monnieri (Level II, Strength B, Direction +)

Brahmi is an Ayurvedic herb traditionally used in the treatment of nervous disorders, including anxiety. While the anxiolytic effects of Bacopa monnieri might be attributed to serotonin, gamma-amino butyric acid (GABA) and/or brain stress hormone modulation,42 the mechanisms of action are still uncertain. Even though data from mechanistic studies are lacking, there is emerging clinical evidence to suggest that brahmi may be useful as a treatment for anxiety. In two similarly designed double-blind RCTs, treatment with brahmi extract (300 mg) significantly reduced state anxiety scores at 12 weeks in healthy adults (n = 46)43 and healthy elderly subjects (n = 48)42 when compared to placebo.

Centella asiatica (Level II, Strength C, Direction +)

Gotu kola is used in Ayurvedic and traditional Chinese medicine as an adaptogenic, nervine tonic and anxiolytic.44 The latter action may be attributed to glutamic acid decarboxylase modulation and subsequent elevations in brain GABA levels.45 With the exception of one double-blind RCT, few studies have explored the efficacy of gotu kola in anxiety. This small trial of 40 healthy volunteers found that, when compared to placebo, the administration of a single 12 g oral dose of gotu kola significantly attenuated the acoustic startle response at 30 and 60 minutes after treatment, but it had no significant effect on self-rated anxiety.46 Further investigation now needs to determine whether these anxiolytic effects are any different following long-term gotu kola administration.

Cymbopogon citratus (Level II, Strength C, Direction o)

This lemongrass variety is native to India. Aside from its role in cooking, the herb is traditionally used as a nervine tonic. Even so, the best available evidence for this herb has not been favourable. In a small double-blind RCT of 18 patients with high trait anxiety scores, a single-dose of lemongrass tea was found to be no more effective than placebo at reducing cognitive test-induced anxiety 30 minutes after administration.47 There is some doubt whether the single-dose administration of the herb, the method of extraction and the short-term outcome measure were appropriate for evaluating the efficacy of lemongrass.

Hypericum perforatum (Level II, Strength C, Direction + (for somatisation complaints only))

St John’s wort is a well-recognised antidepressive agent. Given the serotonergic, domaminergic and GABAminergic activity of the herb,48 it is probable that Hypericum may also be useful as a treatment for anxiety disorder. However, evidence from a number of clinical trials has been inconsistent. An RCT of 151 outpatients suffering from somatisation complaints, for example, found St John’s wort to be statistically significantly superior to placebo in reducing HAM-A total scores, as well as psychic and somatic subscores.49 Yet, in people with social phobia48 and OCD50, Hypericum was found to be no more effective than placebo at improving clinical outcomes. Given the heterogenous patient populations and differences in study duration and size, it is difficult to draw any conclusions from these findings.

Passiflora incarnata (Level I, Strength A, Direction +)

Passionflower is traditionally indicated in nervous system disorders due to its sedative, anxiolytic and hypnotic effects. While the mechanism of action of passionflower is not yet clear, the anxiolytic effect of the constituent chrysin has been linked to the activation of GABA-A receptors.51 Emerging clinical evidence adds further support to this anxiolytic effect. Three RCTs, involving 258 patients, found P. incarnata to be significantly more effective than placebo at reducing preoperative anxiety scores (when administered as a single 500 mg dose),52 and as effective as benzodiazepines at reducing GAD anxiety scores (when administered at a dose of 45 drops per day or 90 mg per day for 4 weeks).53 Since these studies demonstrate low risk of bias, these findings are promising.

Piper methysticum (Level I, Strength B, Direction o)

Kava kava, a native to the Pacific Islands, has long been used as an anxiolytic, sedative and hypnotic agent. Although the modulation of GABA receptors and/or the down-regulation of beta-adrenergic activity may contribute to the anxiolytic effect of the herb, these effects have yet to be confirmed.54 Despite the paucity of mechanistic data, there is a wealth of clinical data on the effectiveness of kava kava in anxiety. In a Cochrane review of 12 double-blind RCTs, of which seven were eligible for meta-analysis, a small but marginally significant reduction in HAM-A total scores was demonstrated in patients receiving P. methysticum when compared to patients receiving placebo.55 Studies postdating this review have yielded inconsistent results.56–59 An updated meta-analysis of the effectiveness of kava kava in anxiety is therefore warranted.

Scutellaria laterifolia (Level III-1, Strength C, Direction +)

Baicalin and baicalein are two constituents of skullcap that have been shown to activate the benzodiazepine binding site of GABA-A receptors,60 which may be responsible for the sedative and anxiolytic effects of the plant. To date, only one published RCT has investigated the anxiolytic effect of skullcap monopreparation. The double-blind, placebo controlled crossover trial compared the effects of three different single doses of skullcap (350 mg vs 200 mg vs 100 mg) to a single-dose placebo in 19 healthy volunteers. The two higher doses of skullcap were found to be most effective at reducing anxiety 60 minutes after administration.61 Given the descriptive nature of the analysis it is uncertain whether the difference between groups was statistically significant.

Valeriana officinalis (Level II, Strength B, Direction o)

Valerian has a long history of use as a sedative, hypnotic and anxiolytic. The anxiolytic effect of Valeriana, in particular, may be credited to glutamic acid decarboxylase stimulation and subsequent elevations in brain GABA levels.45 According to a systematic review of the literature, only one controlled clinical trial has investigated the efficacy of valerian monopreparation in anxiety.53 The 4-week RCT involving 36 patients with GAD found no significant difference between the valerian (50–150 mg daily) and diazepam (2.5–7.5 mg daily) groups, and the valerian and placebo groups in HAM-A total scores.62 Larger studies may help to determine whether valerian is effective in the treatment of anxiety disorder.

Other

Acupuncture (Level I, Strength C, Direction +)

Many studies have examined the effectiveness of acupuncture in anxiety, including GAD, anxiety neurosis, procedure-related anxiety, and substance abuse and withdrawal anxiety, though few of these studies were rigorously designed. A systematic review of 10 RCTs provides the best available evidence for this treatment. The review reports positive findings for the use of acupuncture in the treatment of GAD or anxiety neurosis, and limited evidence in favour of auricular acupuncture in perioperative anxiety.63 The lack of methodological detail and the range of comparative interventions and outcome measures used meant the data were not amenable to meta-analysis and suggests that larger and more rigorously designed studies are needed.

Aromatherapy (Level I, Strength C, Direction o)

The therapeutic application of essential oils can induce a range of psychological effects, including the alleviation of stress and anxiety. These effects are partly supported by a systematic review of six RCTs.64 While the review found a weak positive association between massage aromatherapy (with lavender, orange and/or chamomile essential oil) and anxiety, the effect was transient and the methodological quality of the studies poor. Methodological rigour continues to be a limitation of recent studies, but perhaps the biggest concern with controlled studies on aromatherapy inhalation or massage and anxiety is the paucity of positive findings.65–67 These inconsistent results do little to assist clinicians in making effective clinical decisions about the use of aromatherapy in anxiety disorder.

Chiropractic (Level II, Strength C, Direction o)

Chiropractic manipulation is often used to treat nervous and musculoskeletal disorders. While chiropractic manipulation is not a primary treatment of anxiety, it is not outside the scope of chiropractic care. In fact, a pilot study examining the effect of chiropractic manipulation on salivary cortisol levels suggested chiropractic could cause short-term reductions in client stress and anxiety, with healthy adult male students demonstrating a progressive and statistically significant decrease in cortisol levels from 15 minutes post treatment to 60 minutes post treatment (p<0.05).68 Findings from a RCT demonstrate no significant difference in state anxiety levels between active chiropractic, placebo chiropractic and no treatment control in 21 hypertensive patients.69

Flower essences (Level I, Strength B, Direction o)

Flower essence therapy is an energetic form of medicine that uses the vital force of a flower to treat physiological and psychological complaints, including anxiety.70 According to a systematic review of four placebo-controlled RCTs (n = 370), Bach flower essences were found to be no more effective than placebo at reducing anxiety disorder severity or examination anxiety scores.71 The short duration of these studies (from 3 hours to 14 days), and the predominant use of Bach flower rescue remedy, suggests further investigation is needed to determine whether a longer duration of treatment or the use of other flower essences yields different results.

Homeopathy (Level I, Strength C, Direction o)

Several uncontrolled and observational studies have reported positive changes in anxiety following homeopathic treatment, although the high risk of bias in these studies limits any conclusions that can be made.72 The best available evidence comes from a systematic review of eight RCTs, which found the effectiveness of homeopathy in anxiety disorder, specifically, test anxiety, GAD and anxiety related to medical or physical conditions, was contradictory.72 Meta-analysis of the data was also unsuitable given differences in homeopathic and control interventions, outcome measures and treatment duration.

Massage therapy (Level I, Strength B, Direction +)

Massage is the systematic manipulation of soft tissues of the body. This manipulative therapy may help to reduce anxiety, depression and pain by stimulating parasympathetic nervous system activity, as well as elevating serotonin and endorphin release.8 Many controlled studies have examined the effectiveness of massage therapy in anxiety, including a systematic review of 28 RCTs. This review found that massage therapy (ranging from 5 to 60 minutes per session) significantly improved state and trait anxiety by thirty-seven per cent and seventy-seven per cent, respectively (p<0.01).8 These effect sizes were found to be similar in magnitude to those provided by psychotherapy.8 While these findings are promising, the effect of massage on anxiety in more recent RCTs has been inconsistent.73–76

Reflexology (Level III-2, Strength D, Direction o)

Reflexology is a tactile therapy based on a premise that stimulating specific zones of the feet, hands and/or ears can generate neurophysiological reflexes or responses in distant organs, glands and tissues. Like most tactile therapies, reflexology can also be used to treat stress and anxiety, although evidence of this effect has been inconsistent. In short-term controlled studies, for example, single reflexology treatments in healthy individuals and patients with various types of cancer demonstrated significant anxiety-reducing effects when compared to controls.77–80 In longer term studies, multiple reflexology treatments over a period of 5 days to 19 weeks were found to be no more effective than controls at improving anxiety in individuals experiencing menopause or in patients undergoing cardiac bypass surgery.81,82 These findings highlight the need for much larger studies on the long-term effects of reflexology on anxiety.

CAM prescription

Primary treatments

Secondary treatments

Referral

Review

To determine whether pertinent client goals and expected outcomes have been achieved at follow-up and if any aspects of the client’s care need to be improved, consider the factors listed in Table 8.2 (chapter 8), as well as the questions listed below.

1. Thornhill J.T. Anxiety disorders. In Thornhill J.T., editor: NMS Psychiatry, 5th ed, Baltimore: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2007.

2. Somers J.M., et al. Prevalence and incidence studies of anxiety disorders: a systematic review of the literature. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;51:100-113.

3. Tomb D.A. Psychiatry, 7th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2007.

4. Andreasen N.C., Black D.W. Introductory textbook of psychiatry, 4th ed. Arlington: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2006.

5. Broderick P., Benjamin A.B. Caffeine and psychiatric symptoms: a review. Journal of the Oklahoma State Medical Association. 2004;97(12):538-542.

6. Manzoni G.M., et al. Relaxation training for anxiety: a ten-years systematic review with meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry. 2008;8:41.

7. Miyasaka L.S., Atallah Á.N., Soares B. Passiflora for anxiety disorder. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2007. (1): CD004518

8. Moyer C.A., Rounds J., Hannum J.W. A meta-analysis of massage therapy research. Psychological Bulletin. 2004;130(1):3-18.

9. Beerendonk C., et al. The influence of dietary sodium restriction on anxiety levels during an in vitro fertilization procedure. Journal of Psychosomatic Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1999;20(2):97-103.

10. Wardle J., et al. Randomized trial of the effects of cholesterol-lowering dietary treatment on psychological function. American Journal of Medicine. 2000;108(7):547-553.

11. Wells A.S., et al. Alterations in mood after changing to a low-fat diet. British Journal of Nutrition. 1998;79(1):23-30.

12. Ussher M.H., et al. The relationship between physical activity, sedentary behaviour and psychological wellbeing among adolescents. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2007;42(10):851-856.

13. Wipfli B.M., Rethorst C.D., Landers D.M. The anxiolytic effects of exercise: a meta-analysis of randomized trials and dose-response analysis. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology. 2008;30(4):392-410.

14. Larun L., et al. Exercise in prevention and treatment of anxiety and depression among children and young people. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2006. (3): CD004691

15. Frye B., et al. Tai chi and low impact exercise: effects on the physical functioning and psychological well-being of older people. Journal of Applied Gerontology. 2007;26(5):433-453.

16. Jin P. Efficacy of tai chi, brisk walking, meditation, and reading in reducing mental and emotional stress. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 1992;36(4):361-370.

17. Tsai J.C., et al. The beneficial effects of tai chi chuan on blood pressure and lipid profile and anxiety status in a randomized controlled trial. Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine. 2003;9(5):747-754.

18. Kirkwood G., et al. Yoga for anxiety: a systematic review of the research evidence. British Journal of Sports Medicine. 2005;39(12):884-891.

19. Kozasa E.H., et al. Evaluation of Siddha Samadhi yoga for anxiety and depression symptoms: a preliminary study. Psychological Reports. 2008;103(1):271-274.

20. Michalsen A., et al. Rapid stress reduction and anxiolysis among distressed women as a consequence of a three-month intensive yoga program. Medical Science Monitor. 11(12). 2005:CR555-CR561.

21. Rao M.R., et al. Anxiolytic effects of a yoga program in early breast cancer patients undergoing conventional treatment: a randomized controlled trial. Complementary Therapies in Medicine. 2009;17(1):1-8.

22. Smith C., et al. A randomised comparative trial of yoga and relaxation to reduce stress and anxiety. Complementary Therapies in Medicine. 2007;15(2):77-83.

23. Schruers K., et al. Acute L-5-hydroxytryptophan administration inhibits carbon dioxide-induced panic in panic disorder patients. Psychiatry Research. 2002;113(3):237-243.

24. Kahn R.S., et al. Effect of a serotonin precursor and uptake inhibitor in anxiety disorders; a double-blind comparison of 5-hydroxytryptophan, clomipramine and placebo. International Clinical Psychopharmacology. 1987;2(1):33-45.

25. Benjamin J. Fux M. Belmaker R. (1996) Time course of inositol treatment of panic disorder. Ninth European College of Neuropsychopharmacology Congress. Amsterdam, Netherlands.

26. Palatnik A., et al. Double-blind, controlled, crossover trial of inositol versus fluvoxamine for the treatment of panic disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2001;21(3):335-339.

27. Acil M., et al. Perioperative effects of melatonin and midazolam premedication on sedation, orientation, anxiety scores and psychomotor performance. European Journal of Anaesthesiology. 2004;21(7):553-557.

28. Caumo W., Levandovski R., Hidalgo M.P. Preoperative anxiolytic effect of melatonin and clonidine on postoperative pain and morphine consumption in patients undergoing abdominal hysterectomy: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study. Journal of Pain. 2009;10(1):100-108.

29. Caumo W., et al. The clinical impact of preoperative melatonin on postoperative outcomes in patients undergoing abdominal hysterectomy. Anesthesia and Analgesia. 2007;105(5):1263-1271.

30. Naguib M., Samarkandi A.H. Premedication with melatonin: a double-blind, placebo-controlled comparison with midazolam. British Journal of Anaesthesia. 1999;82(6):875-880.

31. Naguib M., Samarkandi A.H. The comparative dose-response effects of melatonin and midazolam for premedication of adult patients: a double-blinded, placebo-controlled study. Anesthesia and Analgesia. 2000;91(2):473-479.

32. Samarkandi A., et al. Melatonin vs. midazolam premedication in children: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. European Journal of Anaesthesiology. 2005;22(3):189-196.

33. Carroll D., et al. The effects of an oral multivitamin combination with calcium, magnesium, and zinc on psychological well-being in healthy young male volunteers: a double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Psychopharmacology. 2000;150(2):220-225.

34. Gosney M.A., et al. Effect of micronutrient supplementation on mood in nursing home residents. Gerontology. 2008;54(5):292-299.

35. Young G.S., Conquer J. Omega-3 fatty acids and neuropsychiatric disorders. Reproduction Nutrition Development. 2005;45:1-28.

36. Buydens-Branchey L., Branchey M., Hibbeln J.R. Associations between increases in plasma n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids following supplementation and decreases in anger and anxiety in substance abusers. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry. 2007;32(2):568-575.

37. Fontani G., et al. Cognitive and physiological effects of omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid supplementation in healthy subjects. European Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2005;35(11):691-699.

38. Rayman M. The importance of selenium to human health. Lancet. 2000;356:233-241.

39. Benton D., Cook R. The impact of selenium supplementation on mood. Biological Psychiatry. 1991;29(11):1092-1098.

40. Shor-Posner G., et al. Psychological burden in the era of HAART: impact of selenium therapy. International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine. 2003;33(1):55-69.

41. Rayman M., et al. Impact of selenium on mood and quality of life: a randomized, controlled trial. Biological Psychiatry. 2006;59(2):147-154.

42. Calabrese C., et al. Effects of a standardized Bacopa monnieri extract on cognitive performance, anxiety, and depression in the elderly: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine. 2008;14(6):707-713.

43. Stough C., et al. The chronic effects of an extract of Bacopa monniera (brahmi) on cognitive function in healthy human subjects. Psychopharmacology. 2001;156(4):481-484.

44. Bone K. A clinical guide to blending liquid herbs. Missouri, St Louis: Churchill Livingstone; 2003.

45. Awad R., et al. Effects of traditionally used anxiolytic botanicals on enzymes of the gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) system. Canadian Journal of Physiology and Pharmacology. 2007;85(9):933-942.

46. Bradwejn J., et al. A double-blind, placebo-controlled study on the effects of gotu kola (Centella asiatica) on acoustic startle response in healthy subjects. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2000;20(6):680-686.

47. Leite J.R., et al. Pharmacology of lemongrass (Cymbopogon citratus Stapf). III. Assessment of eventual toxic, hypnotic and anxiolytic effects on humans. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 1986;17(1):75-83.

48. Kobak K.A., et al. St. John’s wort versus placebo in social phobia: results from a placebo-controlled pilot study. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2005;25(1):51-58.

49. Volz H.P., et al. St John’s wort extract (LI 160) in somatoform disorders: results of a placebo-controlled trial. Psychopharmacology. 2002;164(3):294-300.

50. Kobak K.A., et al. St John’s wort versus placebo in obsessive-compulsive disorder: results from a double-blind study. International Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2005;20(6):299-304.

51. Zanoli P., Avallone R., Baraldi M. Behavioral characterisation of the flavonoids apigenin and chrysin. Fitoterapia. 2000;71(1):S117-S123.

52. Movafegh A., et al. Preoperative oral Passiflora incarnata reduces anxiety in ambulatory surgery patients: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Anesthesia and Analgesia. 2008;106(6):1728-1732.

53. Miyasaka L.S., Atallah ÁN., Soares B. Valerian for anxiety disorders. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2006. (4): CD004515

54. Sarris J. Herbal medicines in the treatment of psychiatric disorders: a systematic review. Phytotherapy Research. 2007;21:703-716.

55. Pittler M.H., Ernst E. Kava extract versus placebo for treating anxiety. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2003. (1): CD003383

56. Connor K.M., Payne V., Davidson J.R. Kava in generalized anxiety disorder: three placebo-controlled trials. International Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2006;21(5):249-253.

57. Geier F.P., Konstantinowicz T. Kava treatment in patients with anxiety. Phytotherapy Research. 2004;18(4):297-300.

58. Jacobs B.P., et al. An internet-based randomized, placebo-controlled trial of kava and valerian for anxiety and insomnia. Medicine. 2005;84(4):197-207.

59. Lehrl S. Clinical efficacy of kava extract WS 1490 in sleep disturbances associated with anxiety disorders. Results of a multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind clinical trial. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2004;78(2):101-110.

60. Awad R., et al. Phytochemical and biological analysis of skullcap (Scutellaria lateriflora L.): a medicinal plant with anxiolytic properties. Phytomedicine. 2003;10(8):640-649.

61. Wolfson P., Hoffmann D.L. An investigation into the efficacy of Scutellaria lateriflora in healthy volunteers. Alternative Therapies in Health and Medicine. 2003;9(2):74-78.

62. Andreatini R., et al. Effect of valepotriates (valerian extract) in generalised anxiety disorder: a randomised placebo-controlled pilot study. Phytotherapy Research. 2002;16:650-654.

63. Pilkington K., et al. Acupuncture for anxiety and anxiety disorders: a systematic literature review. Acupuncture in Medicine. 2007;25(1–2):1-10.

64. Cooke B., Ernst E. Aromatherapy: a systematic review. British Journal of General Practice. 2000;50:493-496.

65. Holm L., Fitzmaurice L. Emergency department waiting room stress: can music or aromatherapy improve anxiety scores? Pediatric Emergency Care. 2008;24(12):836-838.

66. Muzzarelli L., Force M., Sebold M. Aromatherapy and reducing preprocedural anxiety: a controlled prospective study. Gastroenterology Nursing. 2006;29(6):466-471.

67. Soden K., et al. A randomized controlled trial of aromatherapy massage in a hospice setting. Palliative Medicine. 2004;18(2):87-92.

68. Whelan T.L., et al. The effect of chiropractic manipulation on salivary cortisol levels. Journal of Manipulative and Physiological Therapeutics. 2002;25(3):149-153.

69. Yates R.G., et al. Effects of chiropractic treatment on blood pressure and anxiety: a randomized, controlled trial. Journal of Manipulative and Physiological Therapeutics. 1988;11(6):484-488.

70. Heneka N., White I. Flower essences: Bach flowers/Australian bush flower essences. In: Robson T., editor. An introduction to complementary medicine. Sydney: Allen & Unwin, 2003.

71. Thaler K., et al. Bach flower remedies for psychological problems and pain: a systematic review. BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2009;9:16.

72. Pilkington K., et al. Homeopathy for anxiety and anxiety disorders: a systematic review of the research. Homeopathy: the Journal of the Faculty of Homeopathy. 2006;95(3):151-162.

73. Billhult A., et al. The effect of massage on cellular immunity, endocrine and psychological factors in women with breast cancer: a randomized controlled clinical trial. Autonomic Neuroscience Basic and Clinical. 2008;140(1–2):88-95.

74. Bost N., Wallis M. The effectiveness of a 15 minute weekly massage in reducing physical and psychological stress in nurses. Australian Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2006;23(4):28-33.

75. Campeau M.P., et al. Impact of massage therapy on anxiety levels in patients undergoing radiation therapy: randomized controlled trial. Journal of the Society for Integrative Oncology. 2007;5(4):133-138.

76. Fernandez-Perez A.M., et al. Effects of myofascial induction techniques on physiologic and psychologic parameters: a randomized controlled trial. Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine. 2008;14(7):807-811.

77. McVicar A.J., et al. Evaluation of anxiety, salivary cortisol and melatonin secretion following reflexology treatment: a pilot study in healthy individuals. Complementary Therapies in Clinical Practice. 2007;13(3):137-145.

78. Quattrin R., et al. Use of reflexology foot massage to reduce anxiety in hospitalized cancer patients in chemotherapy treatment: methodology and outcomes. Journal of Nursing Management. 2006;14(2):96-105.

79. Stephenson N.L., et al. Partner-delivered reflexology: effects on cancer pain and anxiety. Oncology Nursing Forum Online. 2007;34(1):127-132.

80. Stephenson N.L., Weinrich S.P., Tavakoli A.S. The effects of foot reflexology on anxiety and pain in patients with breast and lung cancer. Oncology Nursing Forum. 2000;27(1):67-72.

81. Gunnarsdottir T.J., Jonsdottir H. Does the experimental design capture the effects of complementary therapy? A study using reflexology for patients undergoing coronary artery bypass graft surgery. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2007;16(4):777-785.

82. Williamson J., et al. Randomised controlled trial of reflexology for menopausal symptoms. BJOG: an international journal of obstetrics and gynaecology. 2002;109(9):1050-1055.

83. Kuo W.H., Tsai Y.M. Social networking, hardiness and immigrant’s mental health. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1986;27(2):133-149.

84. Tsai J.H. Use of computer technology to enhance immigrant families’ adaptation. Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 2006;38(1):87-93.