CHAPTER 19

Shoulder Arthritis

Definition

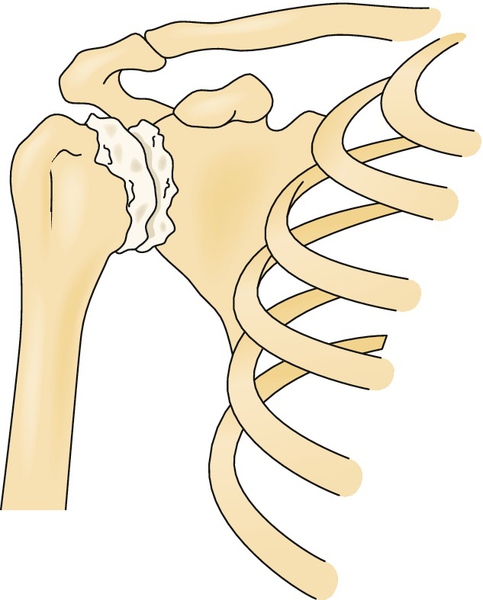

Osteoarthritis of the glenohumeral joint occurs when there is loss of articular cartilage that results in narrowing of the joint space (Fig. 19.1). Synovitis and osteocartilaginous loose bodies are commonly associated with glenohumeral arthritis. Pathologic distortion of the articular surfaces of the humeral head and glenoid can be due to increasing age, overuse, heredity, alcoholism, trauma, Gaucher disease (lipid storage disease), or metabolic disease of bone.

In looking at glenohumeral arthritic conditions, one must consider osteonecrosis both as an etiologic entity and as a related endpoint to the disease. Most of the information about osteonecrosis of the humeral head is extrapolated from the research findings of the disorder of the hip. The major difference between osteonecrosis of the hip and osteonecrosis of the humeral head is that the shoulder bears less weight than the hip. Risk factors are corticosteroid use, radiation therapy, and sickle cell anemia, but its presence in a medically uncomplicated adolescent competitive swimmer [1] does seem to suggest that it may be more common than previously thought.

Shoulder osteoarthritis is most commonly seen beyond the fifth decade and is more common in men. Long-standing complete rotator cuff tears, multidirectional instability from any cause, lymphoma [2] (chronic lymphocytic lymphoma or immunocytoma), or prior capsulorrhaphy for anterior instability [3] can predispose to glenohumeral arthritis.

Acute septic arthritis should not be heedlessly ruled out in the face of severe osteoarthritis [4]. The medical history should include any history of fracture, dislocation, rotator cuff tear, repetitive motion, metabolic disorder, immunosuppression, chronic glucocorticoid administration, and prior shoulder surgery.

Symptoms

Symptoms include shoulder pain intensified by activity and partially relieved with rest. Pain is usually noted with all shoulder movements. Major restriction of shoulder motion and disuse weakness or pain inhibitory weakness are common and potentially progressive. Resultant adhesive capsulitis may be the primary clinical presentation. Pain is typically restricted to the area of the shoulder and may be felt around the deltoid region but not typically into the forearm. Pain is generally characterized as dull and aching but may become sharp at the extremes of range of motion; it is typically worse in the supine position and in attempting to sleep on the arthritic side. Pain may interfere with sleep and may be worse in the morning. Neurologic symptoms, such as numbness and paresthesias, should be absent.

Physical Examination

Restriction of shoulder range of motion is a major clinical component, especially loss of external rotation and abduction. Both active and passive range of motion is affected in shoulder arthritis, compared with only active motion in rotator cuff tears (passive range is normal in rotator cuff injuries unless adhesive capsulitis is present). Pain increases when the extremes of the restricted motion are reached, and crepitus is common with movement. Tenderness may be present over the anterior rotator cuff and over the posterior joint line.

Several well-described tests for examination of the shoulder are commonly used in clinical practice (e.g., Neer, Hawkins-Kennedy, Yergason, painful arc, and compression-rotation test). Pooled sensitivity and specificity range from 53% to 95%, yet meta-analysis has demonstrated that use of any single shoulder examination test to make a diagnosis cannot be unequivocally recommended. Combinations of tests provide better accuracy, but marginally so. These findings seem to provide support for stressing a comprehensive clinical examination [5].

If acromioclavicular joint osteoarthritis is an accompanying problem, the acromioclavicular joint may be tender. There may be wasting of the muscles surrounding the shoulder because of disuse atrophy. Sensation and deep tendon reflexes should be normal. In patients with inconsistent physical examination findings and questionable secondary gain issues, the American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons subjective shoulder scale has demonstrated acceptable psychometric performance for outcomes assessment in patients with shoulder instability, rotator cuff disease, and glenohumeral arthritis [6]. Additional scoring systems, such as the Hospital for Special Surgery score and the validated Western Ontario Osteoarthritis of the Shoulder Index, may be of clinical or research utility [7].

Functional Limitations

Any activities that require upper extremity strength, endurance, and flexibility can be affected. Most commonly, activities that require reaching overhead in external rotation are limited. These include activities of daily living (such as brushing hair or teeth, donning or doffing upper torso clothes) and activities such as throwing or reaching for items overhead. If pain is severe and constant, sleep may be interrupted, sleep-wake cycle disruption may occur, and situational reactive depression is not uncommon, especially with a shoulder pain syndrome that has exceeded 3 months [8].

Diagnostic Studies

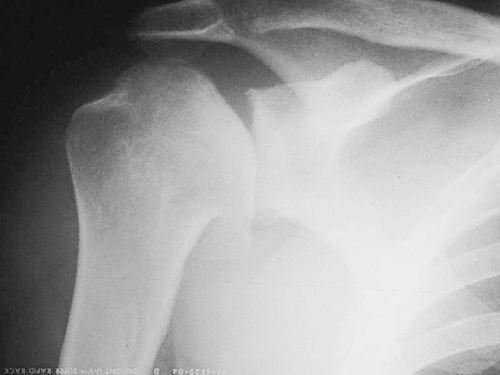

Routine shoulder radiographs with four views (anteroposterior internal and external rotation, axillary, and scapular Y) are generally sufficient for evaluating loss of articular cartilage and glenohumeral joint space narrowing (Fig. 19.2). Varying degrees of flattening of the humeral head, marginal osteophytes, calcific tendinitis, subchondral cysts in the humeral head and glenoid, sclerotic bone, bone erosion, and humeral head migration may be seen. Specifically, if there is a chronic rotator cuff tear that is contributing to the destruction of the articular cartilage, the humeral head will be seen pressing against the undersurface of the acromion. Associated acromioclavicular joint arthritis can be seen on the anteroposterior view.

Conventional magnetic resonance imaging is the “gold standard” to assess soft tissues for rotator cuff tear; but when more sensitive evaluation of the labrum, capsule, articular cartilage, and glenohumeral ligaments is required or when a partial-thickness rotator cuff tear is suspected, magnetic resonance arthrography with intra-articular administration of contrast material may be required to visualize these subtle findings [9]. Paralabral cysts (extraneural ganglia), which can result with posterior labrocapsular complex tears and cause suprascapular nerve compression, may be visualized on magnetic resonance imaging [10].

Computed tomography may have a unique role in finding posterior humeral head subluxation relative to the glenoid in the absence of posterior glenoid erosion [11]. A rise in popularity of diagnostic ultrasonography in musculoskeletal medicine is undeniable. The modality may play a role in the diagnosis of full-thickness rotator cuff tear in experienced hands, but significant inter-rater reliability has been called into question [12,13], and diagnostic ultrasonography would play a minimal role in the diagnosis of glenohumeral arthritic conditions.

Electrodiagnostic medicine consultation will help rule out idiopathic brachial plexopathy (Parsonage-Turner syndrome), cervical radiculopathy, and isolated suprascapular, dorsal scapular, or axillary neuropathy. The sensory irritative component of spinal or peripheral nerve irritation will usually yield a normal result, but H reflexes to median nerve stimulation at the level of the elbow may be suggestive of C5-C6 radiculitis, whereas findings on needle electromyography would be normal.

Complete blood counts, coagulation profile, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and blood cultures may be in order. In addition, the author encourages that any woman with shoulder pain recalcitrant to seemingly appropriate treatment be considered for mammography.

Treatment

Initial

Shoulder arthritis is a chronic condition, but acute exacerbations in pain can be managed conservatively. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or analgesic medications can help with pain and enable rehabilitation. Capsaicin cream, lidocaine patches, ice, or moist heat may be used topically as needed. Gentle stretching exercises help maintain the range of motion and prevent secondary adhesive capsulitis and sequelae of immobility.

Rehabilitation

The shoulder is a complicated structure composed of several joints with both static and dynamic stabilizers that tend to function, and fail, as a unit. A well-designed rehabilitation program must take this into account and treat glenohumeral arthritic conditions within this context. The rehabilitative efforts are dedicated to the restoration of strength, endurance, and flexibility of the shoulder musculature. Supervised physical or occupational therapy should focus on the upper thoracic, neck, and scapular muscle groups but address the entire upper extremity kinetic chain, including the rotator cuff, arm, forearm, wrist, and hand. Patients benefit from aquatic therapy and can easily be taught exercises and then transitioned to an independent pool exercise program that they can continue long term. In cases of severe rheumatoid arthritis, joint-sparing static exercises may prevent atrophy and maintain strength of dynamic stabilizers of the shoulder without placing undue stress on the remaining articular surfaces. Joint-sparing exercises such as isometric contraction within normal range of motion will strengthen shoulder stabilizers, minimize joint damage, and decrease induction of the inflammatory cascade that often drives arthritic patients to seek health care. The consensus [14] on glenohumeral involvement in rheumatoid arthritis is that narrowing of the joint space is a turning point indicating a risk of rapid joint destruction, and surgical interventions should be considered before musculoskeletal sequelae are too severe to enable adequate recovery. Postoperative care, although it depends on the operative intervention, should focus on maintenance of functional range of motion and prevention of adhesive capsulitis but be balanced with avoidance of dislocation or damage to the repaired labrum. Range of motion after total shoulder arthroplasty will be considerably less than in the shoulder not operated on. Suprascapular nerve block may have a role in helping the patient tolerate postoperative therapies.

The success of flexibility exercises will be determined by the extent of mechanical bone blockade, which in turn is determined by the magnitude of glenohumeral incongruous distortion, presence of loose bodies, and osteophyte formation. Pain control can be assisted with modalities such as ultrasound and iontophoresis. Electrical stimulation may have a limited role in posterior shoulder strengthening in patients with poor posture and “rounded shoulders” on examination, but it should not take the place of volitional contraction and not be used routinely across arthritic joints. In caring for arthroplasty patients, the Neer protocol for postoperative total shoulder arthroplasty rehabilitation is widely used and based on tradition and the basic science of soft tissue and bone healing [15].

Procedures

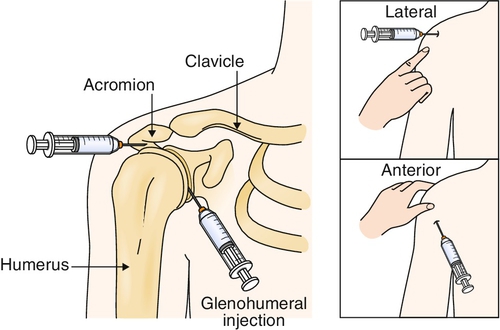

If therapies fail or are impossible because of pain, the patient has several options. Periarticular injections may offer some help to control pain of associated problems, such as subacromial bursitis and rotator cuff tendinopathy. Wide variations exist in local anesthetic doses and techniques. On the other hand, steroid doses do not vary as widely with methylprednisolone acetate and triamcinolone acetonide, the most commonly used agents [16]. Intra-articular glenohumeral joint injections may also afford some pain relief, particularly in the early stages. The accuracy of intra-articular injections not fluoroscopically guided is less than perfect at 80%; the anterior approach is slightly more accurate than the posterior approach at 50% [17]. However, injections have not been shown to alter the underlying arthritis pathoanatomy (Fig. 19.3). Great care should be taken in anticoagulated patients. Viscosupplementation (hylan G-F 20) is not approved by the Food and Drug Administration for the glenohumeral joint, but the author has empirically seen it play a role in comprehensive care of mild osteoarthritis.

The initial setup can be identical for either intra-articular glenohumeral or subacromial injection. With the patient seated with the arm either in the lap or hanging down by the side, the internal rotation and gravity pull of the arm will open the space, leading to the glenohumeral joint or subacromial space. Several approaches have been described. Most commonly for a subacromial injection, the skin entry point is 1 cm inferior to the acromion, and the needle is tracked anteriorly at a lateral to medial 45-degree angle in the axial plane and slightly superior (under the acromion). The injectate should flow with minimal resistance into this potential space. If resistance is encountered, the needle should be repositioned to avoid intratendinous injection, which can increase the risk of tendon rupture. For glenohumeral injection, a more inferior and medial approach is used (Fig. 19.4).

Postinjection care includes awareness of the local anesthetic effects and avoidance of impingement or maneuvers at end range of motion. Patients are cautioned to avoid aggressive activities for the first few days after the injection. If the adhesive capsulitis component is specifically being treated, a suprascapular nerve block with 5 to 10 mL of 0.25% bupivacaine (Marcaine) with or without epinephrine can be performed immediately before therapy, with an appropriately trained therapist aware of the safe handling of such an anesthetized joint. The author typically employs a combined suprascapular and subacromial approach in these cases and coordinates follow-up appointments with occupational therapy. This should be done only with properly trained therapists who are aware of the postinjection proprioceptive loss.

Surgery

If unacceptable symptoms persist despite conservative treatment, the patient may decide to reduce his or her activity level to minimize pain or proceed with one of a number of surgical interventions. It is important to inform the patient that regardless of the treatment approach, with osteoarthritis, a return to normal shoulder function, by either rehabilitation or surgery, is not possible. However, pain control and some increased function are usually achievable.

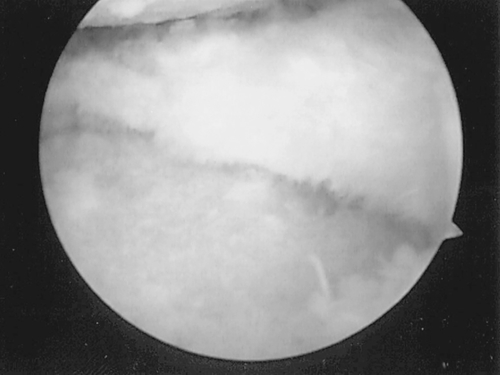

Surgical options include débridement of the glenohumeral joint by open or arthroscopic techniques and hemiarthroplasty or total shoulder arthroplasty. If reasonable congruity between the humeral head and glenoid is present, good improvement in pain control and some functional improvement can be anticipated with débridement, even in the presence of severe chondromalacia. The glenoid may be amenable to arthroscopic resurfacing with a meniscal allograft [18]. Other biologic surfaces include anterior capsule, fascia lata autograft, Achilles tendon allograft, and cartilage-preserving arthroscopic spongioplasty [19]. However, inconsistent results and high complication rates are seen, and a trend toward arthroplasty is occurring. Other arthroscopic techniques are successful, provided osteophytes and loose bodies are removed (Fig. 19.5) [20]. Hemiarthroplasty may be indicated in the absence of advanced glenohumeral disease if the glenoid can at least be converted to a smooth concentric surface [21]. Shoulder hemiarthroplasty volumes and rates increased at annual rates of 6% to 13% from 1993 to 2007, with a revision increase from 4.5% to 7%, and procedures are predicted to increase by 192% to 322% by 2015 [22]. Hemiarthroplasty has also been suggested as the procedure of choice in moderate to severe glenohumeral arthritis and irreparable rotator cuff tears [23]; it may have other indications in avascular necrosis, glenohumeral chondrolysis, tumor, or complete deltoid denervation with subluxation and secondary osteoarthritis [24].

If major incongruity is present between the humeral head and glenoid, total shoulder arthroplasty may be indicated [25]. There is some suggestion of better long-term outcomes when biceps tenodesis is performed concomitantly with shoulder arthroplasty [26]. Although it may seem counterintuitive, proprioception actually improves after total shoulder arthroplasty over prearthroplasty measurements [27]. This is important from the standpoint of activities of daily life in osteoarthritic patients. Most shoulders, however, can be aided arthroscopically with appropriate technique, which often necessitates a second posterior portal and a highly experienced shoulder arthroscopist [20]. Although a greater risk of more advanced glenohumeral arthritis is associated with arthroscopic procedures that result in limited external rotation [28], arthrodesis may be required for irreversible and non-reconstructible massive rotator cuff tears, tumor, and deltoid muscle denervation as well as for detachment of the deltoid from its origin or to stabilize the glenohumeral joint after many failed attempts at shoulder reconstruction [29]. Arthrodesis for failed prosthetic arthroplasty or tumor resection presents additional challenges and additional risk of the aforementioned complications. A newer procedure, thermal capsulorrhaphy, has come in and out of favor; it is usually used more in high-functioning athletes for isolated posterior instability without labral detachment rather than in isolated glenohumeral osteoarthritis [30].

Potential Disease Complications

Disease complications include chronic intractable pain and loss of shoulder range of motion. These result in diminished functional ability to use the arm, disuse weakness, difficulty with sleep, inability to perform work and recreational activities, and reactive depression. Isolated nerve injury or brachial plexopathy may result.

Potential Treatment Complications

Analgesics and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs have well-known side effects that most commonly affect the gastric, hepatic, and renal systems. Infection, hemarthrosis, and allergic reaction to the medications are rare side effects of injections. In particular, there may be an association between subdeltoid septic bursitis and concomitant systemic isotretinoin (Accutane) [31]. Fluid retention or transient hyperglycemia may be seen with a single exogenous glucocorticoid injection. Arthroscopic complications are not common, but the usual possibilities, including neurovascular issues, have been reported. Arthrodesis complications include nonunion, malposition, pain associated with prominent hardware, and periarticular fractures. Arthrodesis after cancer reconstruction has a higher risk of complication [29].