Gastrointestinal Medications

Objectives

1. Identify common uses for antacids and histamine H2-receptor antagonists.

3. Compare the actions and adverse reactions of the five major classifications of laxatives.

5. Describe indications for disulfiram use and what is meant by “disulfiram reaction.”

Key Terms

antacids (ănt-ĂS-ĭdz, p. 336)

antidiarrheals (ăn-tĭ-dī-ă-RĒ-ălz, p. 340)

antiflatulents (ăn-tĭ-FLĂ-tū-lěnts, p. 347)

digestive enzymes (dī-JĔS-tĭvĔN-zīmz, p. 349)

disulfiram reaction (dī-SŬL-fĭ-răm, p. 350)

emetics (ěm-ĔT-ĭks, p. 347)

histamine H2-receptor antagonists (HĬS-tă-mēn, ăn-TĂG-ō-nĭsts, p. 336)

laxatives (LĂK-să-tĭvz, p. 341)

motility (mō-TĭL-ĭ-tē, p. 340)

Overview

![]() http://evolve.elsevier.com/Edmunds/LPN/

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Edmunds/LPN/

This chapter discusses medications used to treat the many diseases and disorders that affect the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. Many of these drugs are available over the counter (OTC); many others are used, often in combination, to relieve the symptoms of common GI tract problems.

There are three major types of GI medications. The first type includes products designed to help restore or maintain the lining that protects the GI tract. These drugs include antacids, which act to neutralize or reduce the acidity of the gastric contents; histamine H2-receptor antagonists, which reduce gastric acid secretion by limiting the action of histamine at the H2 receptors in the stomach; and proton pump inhibitors, which reduce gastric acid by blocking the proton pump. These medications are described in the first section.

A second type of GI medication affects the general motility, or movement, of the GI tract. These medications include the anticholinergics and antispasmodics, which not only reduce gastric motility but also decrease the amount of acid secreted by the stomach, and the antidiarrheals, which reduce diarrhea by slowing the intestinal peristalsis. These drugs are discussed in the second section.

The third type of GI drugs also affect motility, but their action is primarily in the colon. These are the laxative agents. These preparations promote bowel emptying in a variety of ways. They may increase intestinal bulk, lubricate the intestinal walls, soften the fecal mass by retaining water, or produce increased peristalsis through local tissue irritation or by direct action on the intestine. These drugs are discussed in the third section.

The fourth section presents miscellaneous medications. These preparations include antiflatulents, which are used to reduce gas and bloating; and digestive enzymes, which are used in deficiency states to break down fats, starches, and proteins in the digestive process. (Antiemetic preparations are discussed in Chapter 16, along with antivertigo agents.)

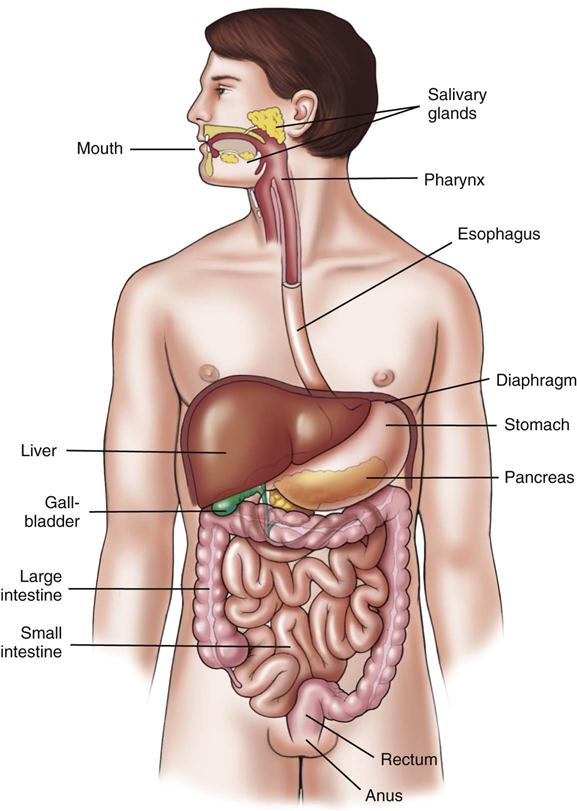

Digestive System

The digestive system is composed of the mouth, esophagus, stomach, intestines, and accessory structures (Figure 19-1). This system performs the mechanical and chemical process of digestion, absorbs nutrients, and eliminates waste.

Digestion begins in the mouth with chewing and mixing of food with enzyme-rich saliva secreted by salivary glands. The passages and spaces from the mouth to the anus are called the alimentary canal. Here is where the complex compounds created in the mouth are reduced to soluble substances that can be absorbed; the usable food substances are absorbed; and the indigestible and waste material is eliminated. The digestive glands secrete enzymes and other chemicals essential to the breakdown of food substances and their absorption into the bloodstream. The salivary glands, gallbladder, liver, and pancreas are included as accessory glands.

Almost all oral medications use the digestive system as a means to reach target organs or tissues. Many of the side effects, such as diarrhea, nausea, or constipation, are results of the direct action of medications on the alimentary tract itself. Medications, as well as all swallowed materials, are acted on by the digestive tract and are metabolized and excreted.

The digestive tract must work without being destroyed by the strong acid it makes to digest food. Several factors work together to protect the GI tract mucosa from injury. The gastric mucosal barrier resists backward diffusion of hydrogen and thus has the ability to have a high concentration of hydrochloric acid (HCl) within the gastric lumen unless something breaks this barrier. Endogenous prostaglandins (those produced in the GI tract) are thought to protect the cells against agents that would be harmful. Prostaglandins are produced in great numbers in the mucosa of the stomach and duodenum. They are known to produce both mucus and bicarbonate and to maintain mucosal blood flow. Mucus helps protect the mucosa. It is secreted by surface epithelial cells and forms a gel that covers the mucosal surface and physically protects the mucosa from abrasion. It also resists the passage of large molecules such as pepsin. Bicarbonate is produced in small amounts by surface epithelial cells and moves up from the mucosa to create a thin layer of alkalinity between the mucus and the epithelial surface. Other protective factors include mucosal blood flow, epithelial healing or renewal, and epidermal growth factor that is secreted in saliva and by the duodenal mucosa.

There is a lot of variability in the body’s ability to absorb medications from the GI tract over the course of a lifetime. Changes in GI blood flow, amount of surface available, and motility are found in very young and older adult patients. Thus dosages of some medications may need to be changed when the patient is very young or very old.

Antacids, H2-Receptor Antagonists, Proton Pump Inhibitors

Overview

The lining of the stomach is usually strong enough to resist the powerful digestive juices and acids that bathe it. When stress or disease produce excess secretion of gastric acids, or when there is destruction of the protective mucosal lining because of alcohol, chemicals, or disease, gastric distress is produced. If the protective lining is not repaired or the gastric acid level reduced, duodenal, gastric, or peptic ulcers are produced, leading to increased pain and bleeding. Antacid therapy, histamine H2-receptor antagonists, and proton pump inhibitors reduce gastric acidity and promote healing. More than one medication may be used at the same time to help in healing. Two unique medications, sucralfate and misoprostol, are designed to assist in the protection of GI mucosa from the effects of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs).

Action

Antacids are OTC agents that neutralize HCl and increase gastric pH, thus inhibiting pepsin (a gastric enzyme). Antacids work in a variety of ways. Some antacids cause hydrogen ion absorption (buffering the acid), tightening of the gastric mucosa, and increased tone of the cardiac sphincter. Formation of gas that may be released by burping is another way in which antacids work.

Histamine H2-receptor antagonists are unique, because they promote healing of ulcers and act with antacids to produce more alkaline conditions in the GI tract. Histamine H2-receptor antagonist drugs can bind to the H2 receptor, thereby displacing histamine from receptor binding sites and preventing stimulation of the secretory cells. Thus they block histamine, inhibit the secretion of gastric acid, and are rapidly absorbed; they reach their peak of effectiveness in 45 to 90 minutes.

Another class of drugs that works to heal gastric ulcers is proton pump inhibitors. These drugs irreversibly stop the acid secretory pump embedded within the gastric parietal cell membrane by altering the activity of H+, K+-ATPase, the enzyme inhibiting hydrogen ion transport into the gastric lumen, and thus decrease acid secretion. Because proton pump inhibitors act on the basolateral membrane of the parietal cells, they do not affect gastric emptying, basal or stimulated pepsin output, or secretion of intrinsic factor. These drugs do not seem to affect the level of adenosine triphosphatase (ATPase) of other organ systems.

Uses

Antacids are used with other drugs to treat peptic ulcer disease, gastritis, gastric ulcer, peptic esophagitis, hiatal hernia, gastric hyperacidity, and esophageal reflux.

Histamine H2 blockers are generally considered first-line therapy to relieve symptoms and prevent complications of peptic ulcer disease when used for 6 to 8 weeks. (It is common for the patient to have a relapse after the medication is stopped.) They are also used in the prophylaxis and treatment of peptic esophagitis, benign gastric ulcers, duodenal ulcers, stress ulcers, and Zollinger-Ellison syndrome. The H2 blockers are similar in effectiveness and side effects.

Many peptic ulcers may be caused by Helicobacter pylori. This organism may be controlled and the ulcer healed by use of antibiotics plus products such as ranitidine.

Proton pump inhibitors are used in the short-term treatment of active duodenal ulcers, usually after adequate courses of H2-receptor antagonists have not been successful. Longer therapy is not indicated. Severe erosive esophagitis and poorly responsive gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) are indications for these types of medications as well. Long-term treatment with proton pump inhibitors is needed for pathologic hypersecretory conditions.

There are other important drugs that do not fit into these three categories but also assist in the healing of ulcers. Sucralfate is an aluminum salt of sulfated sucrose and a polysaccharide with antipeptic activity. It aids in the healing of ulcers by forming a protective layer at the ulcer site, providing a barrier to hydrogen ion diffusion, but does not alter gastric pH. It also works to stop pepsin’s action and adsorbs bile salts. Misoprostol is a synthetic prostaglandin analogue with both an antisecretory and a mucosal protective action. It is indicated for use in patients who have gastric distress or ulceration secondary to the use of NSAIDs.

Adverse Reactions

Some adverse reactions occur only with a certain category of antacids; others are common to most. Antacids may produce malaise (weakness), anorexia (lack of appetite), bowel obstruction, constipation, diarrhea, frequent burping, thirst, and muscle weakness. In cases of extreme hypermagnesemia, cardiotoxicity with bradyarrhythmia (slow heart beat), asystole (no heart beat), and hypotension may be seen. The most severe reactions include coma, decreased reflexes, and respiratory depression.

With histamine H2-receptor antagonists, side effects are unusual, but the patient may have mild and self-limiting problems such as dizziness, headaches, somnolence, mild and brief diarrhea, some hematologic changes, rash, impotence, mild gynecomastia (enlargement of the breasts in men), muscle pain, and fever. With proton pump inhibitors, reactions include headache, diarrhea, abdominal pain, and nausea. Rare reactions include rash, vomiting, and dizziness.

Drug Interactions

Antacids prevent the absorption of the antibiotic tetracycline. Enteric coatings of various medications dissolve more quickly in the presence of antacids, leaving the upper GI tract more sensitive to irritation. Some antacids have been known to either bind with or alter the absorption rate of digitalis products, anticoagulants, iron, phenothiazines, antiinflammatory agents, antihypertensives, antiarthritic agents, hydantoin, and possibly propranolol. Aluminum-magnesium hydroxide gel may increase absorption of aspirin.

Antacids may increase the absorption of cimetidine, a histamine antagonist agent. Cimetidine may increase the effects of anticoagulants, hydantoin, beta-adrenergic blocking agents, lidocaine, benzodiazepine derivatives, and theophylline. Decreased white blood cell counts have been reported in cimetidine-treated patients who also received other drugs and treatments known to produce neutropenia. Apnea, confusion, and muscle twitching may be produced when cimetidine is administered with morphine. Serum digoxin levels may be reduced when digoxin and cimetidine are administered together. Cigarette smoking may neutralize the action of cimetidine. Ranitidine does not appear to interact with warfarin-type anticoagulants, theophylline, or diazepam, although it does produce false-positive urine protein tests.

Proton pump inhibitors also inhibit the cytochrome P-450 system and may interfere with the metabolism of other drugs using the P-450 system. They may also increase concentration of oral anticoagulants, diazepam, and phenytoin, making overdosage a possibility.

Nursing Implications and Patient Teaching

Nursing Implications and Patient Teaching

n Assessment

Learn everything possible about the patient’s health history, including GI symptoms, the presence of disease (especially renal failure), the presence of allergy, and whether any medications that might cause drug interactions are currently being taken by the patient.

n Diagnosis

In addition to the medical diagnosis, what is the source of the patient’s problem? Does the patient drink too much coffee or alcohol or use cigarettes extensively—all of which are harmful to the gastric mucosa? Is the patient under stress from financial, family, or job-related difficulties? Does the patient experience gastric distress because of other medications (such as NSAIDs) or disease processes? Look beyond the symptoms to find the cause of increased gastric acid production. This may assist the patient in focusing on the true source of the problem.

n Planning

The patient’s fluid intake should be increased, and the patient who is taking antacids that cause constipation, such as those containing calcium or aluminum, should be carefully monitored. These drugs may be alternated with antacids that have cathartic-like actions, such as those containing magnesium.

n Implementation

Antacids are available in several different forms. Liquids or solutions are the preferred choice whenever possible, because they neutralize acid more rapidly. Suspensions, gels, chewable tablets, effervescent tablets, and powders are also available. Tablets should be considered the last alternative, even though they may be the patient’s first choice. The gastric emptying time of the peptic ulcer patient may vary, so it is wise to individualize the antacid schedule. The neutralizing abilities of antacids vary, requiring different quantities of medication, depending on the product. Discuss flavor preferences with the patient. Many patients discontinue antacid therapy because they dislike the flavor. Products come in many flavors, and various drugs may be tried if compliance becomes a problem.

Antacids with a laxative effect should be taken at bedtime to allow adequate rest before the bowel is stimulated.

The sodium content of various antacids must be carefully assessed before giving them to patients who are on restricted sodium intake. These patients include pregnant women and patients with congestive heart failure (CHF) or other cardiac conditions, hypertension (high blood pressure), edema (fluid buildup in the body tissues), or renal failure.

Histamine H2-receptor antagonists may be given via intravenous (IV) or oral (PO) medications. Preparations given PO should be given with meals and at bedtime. IV injections should be diluted and injected over 1 to 2 minutes or given by infusion, and are usually given to patients with hypersecretion of gastric acid or intractable pain from ulcers. These medications should be given for 2 to 6 weeks, until endoscopy tests reveal healing. This drug may mask underlying malignancy.

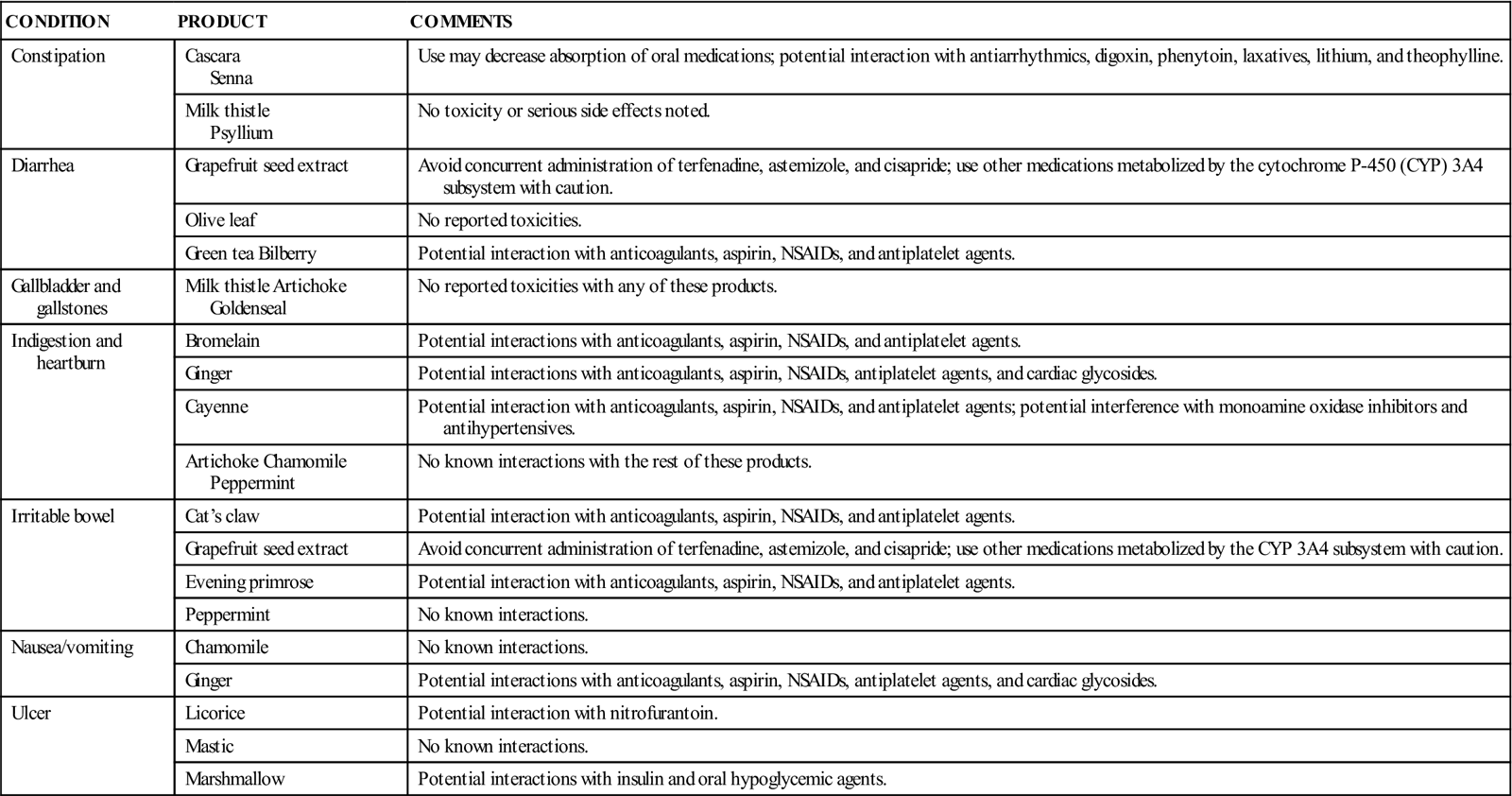

Table 19-1 presents a summary of antacids and histamine H2-receptor antagonists.

![]() Table 19-1

Table 19-1

Antacids, Histamine H2-Receptor Antagonists, and Proton Pump Inhibitors

| GENERIC NAME | TRADE NAME | COMMENTS |

| Antacids | ||

| aluminum carbonate gel | Basaljel | Take between meals and at bedtime, followed by a sip of water if desired. |

| aluminum hydroxide gel | Dialume | Helps delay stomach emptying and binds bile salts. Drug of choice in peptic ulcer disease. Take between meals and at bedtime, followed by a sip of water if desired. |

| calcium carbonate | Tums | Very effective; promotes prolonged and powerful neutralizing effect greater than aluminum hydroxide. Primarily suited for short-term therapy; given in small doses. Constipating effects may be minimized by alternating with doses of a magnesium-containing antacid such as magnesium carbonate. |

| magaldrate | Losopan Riopan |

Combination of magnesium and aluminum hydroxide. Effectiveness depends on GI pH. Give between meals and at bedtime; not to be taken for more than 2 wk. |

| magnesium hydroxide | Milk of Magnesia | Helpful because cathartic effect counteracts constipation of aluminum hydroxide. Osmotic diarrhea may occur when given alone. Take with water up to 4 times daily. |

| magnesium oxide | Mag-Ox Maox Uro-Mag |

Acts more slowly than sodium bicarbonate but has a more prolonged action and increased neutralizing ability. As with other magnesium antacids, osmotic diarrhea may develop, but it may be alleviated if alternated with aluminum or calcium salts. |

| sodium bicarbonate | Bell/ans | Take 1 to 4 times/day. |

| sodium citrate | Citra pH | Take daily. |

| Antacid Combinations | ||

| aluminum hydroxide and magnesium hydroxide | Maalox | Combined to provide a nonconstipating, noncathartic antacid for relief of hyperactivity of peptic ulcer. Suspension may be followed by a sip of water. |

| aluminum hydroxide, magnesium hydroxide, and simethicone | Gelusil | Products use simethicone to reduce gas formation; come in many flavors and a variety of combinations. |

| calcium carbonate | Titralac | Form an insoluble antacid-protective compound for the relief of hyperacidity. Take after meals; tablets can be chewed, swallowed, or allowed to dissolve slowly in the mouth. |

| Histamine H2-Receptor Antagonists | ||

| cimetidine | Tagamet | Widely used in prophylaxis and treatment of ulcers. Has more drug interactions than other preparations and a much wider range of actions than other preparations. Should be taken with antacids. |

| famotidine | Pepcid | Reduce dose in those with decreased renal function. |

| nizatidine | Axid | Give reduced dose for those with decreased renal function. |

| ranitidine | Zantac | Similar in action to cimetidine, but has fewer drug interactions. Headaches are frequent; extrapyramidal symptoms may be noted. Dose should not exceed 150 mg/24 hr if creatinine clearance is below 50 mL/min. |

| Agents to Treat Helicobacter pylori | ||

| bismuth subsalicylate, metronidazole, and tetracycline | Helidac Pylera |

Each dose includes 4 pills: 2 pink chewable 262.4-mg tablets (bismuth subsalicylate); 1 white 250-mg tablet (metronidazole); and 1 pale orange and white 500-mg capsule (tetracycline). Patient should take each dose 4 times daily, with meals and at bedtime, chew and swallow pink tablets, swallow others whole, and drink plenty of water with medication, especially at night. |

| Miscellaneous Products | ||

| misoprostol | Cytotec | Take daily with meals and at bedtime; reduce dose if higher dose cannot be tolerated. Patient should use throughout the course of NSAID therapy. |

| sucralfate | Carafate | Antacids may be prescribed as needed for pain relief, but patient should not take within  hr before or after this medication. hr before or after this medication. |

| Proton Pump Inhibitors | ||

| esomeprazole | Nexium | Take delayed-release capsule 1 hr before eating. |

| lansoprazole | Prevacid |

Adults: 15 mg once daily before meals for 4 wk. May also use 30 mg with 500 mg clarithromycin and 1 g amoxicillin twice daily for 14 days; or 30 mg with 1 g amoxicillin 3 times daily for 14 days for those intolerant to clarithromycin. |

| omeprazole | Losec Prilosec |

Adults: 20 mg daily before eating for 4-8 wk. Most ulcers heal within 4 wk, but some require an additional 4 wk. Do not open, chew, or crush capsule. |

| pantoprazole | Protonix | Use delayed-release capsule once daily for 8 wk; also available as an IV infusion. |

| rabeprazole | Aciphex | Use delayed-release tablet every morning for 4-8 wk. |

GI, Gastrointestinal; IV, intravenous; NSAID, nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug.

n Evaluation

Watch to see if the patient seems to have less GI distress or develops any adverse reactions.

n Patient and Family Teaching

Anticholinergics, Antispasmodics, and Antidiarrheals

Overview

Motility is the spontaneous but unconscious or involuntary movement of food through the GI tract. Much of the discomfort of GI disease is caused by increased intestinal peristalsis (muscle contraction). Abdominal cramping, bloating, and pain may be related either to acute minor illnesses associated with diarrhea and increased gas, or to chronic diseases such as ulcers or colitis. Also, many drugs have both diarrhea and increased bowel motility as common adverse reactions.

The medications used to treat these problems are classified as anticholinergics, antispasmodics, or antidiarrheals. Their actions are somewhat different, although they are often used interchangeably.

Action

The anticholinergic-antispasmodic agents are parasympatholytic drugs (natural and synthetic) that act with antacids in prolonging or continuing the therapeutic benefits of both drug categories. Anticholinergics reduce GI tract spasm and intestinal motility, acid production, and gastric motility and thus reduce the associated pain. Gastric emptying time is slowed, and neutralization is increased. Pancreatic secretions of fluid, electrolytes, and enzymes are also stopped. However, the adverse reactions resulting from the high dosages necessary to obtain these effects make the use of such dosages questionable. GI motility stimulants are also available and are particularly helpful in the elderly patient with GERD because they do not have cholinergic activity.

Antidiarrheals reduce the fluid content of the stool and decrease peristalsis and motility of the intestinal tract. They increase smooth muscle tone and diminish digestive secretions. The bismuth salts absorb toxins and provide a protective coating for the intestinal mucosa.

Uses

Anticholinergic-antispasmodic agents are used primarily to treat peptic ulcer, pylorospasm, biliary colic, hypermotility, hyperacidity, irritable colon, and acute pancreatitis.

Antidiarrheals are used to treat nonspecific diarrhea or diarrhea caused by antibiotics.

Adverse Reactions

Adverse reactions are common in anticholinergic therapy because high dosages are usually required. The most common adverse reactions include rapid, weak pulse; blurring of vision; dysphagia (difficulty swallowing); difficulty talking; dilation of pupils; drowsiness; excitation; photophobia (sensitivity to light); confusion; restlessness; staggering; talkativeness; rash primarily over the face, neck, and upper trunk (especially in children); flushing of skin; constipation; dry mouth; great thirst; urinary urgency; and difficulty emptying the bladder. Anticholinergics containing phenobarbital may produce convulsions, delirium, excitement, musculoskeletal pain, and various dermatologic and allergic responses. Antidiarrheals may cause tachycardia (rapid heartbeat), dizziness, drowsiness, fatigue, headache, sedation, pruritus (itching), urticaria (hives), abdominal distention, constipation, dry mouth, nausea, vomiting, urinary retention, and physical dependence.

Drug Interactions

Anticholinergics containing phenobarbital may decrease the effects of anticoagulants, requiring higher doses of the anticoagulant. Anticholinergics have many drug interactions (see Chapter 16 for a more specific discussion). The newer GI stimulants may cause serious dysrhythmias (irregular heartbeats) when given with other drugs that inhibit the cytochrome P-450 3A4 system and must be used with caution.

Nursing Implications and Patient Teaching

Nursing Implications and Patient Teaching

n Assessment

Learn everything possible about the patient’s health history, including the presence of allergy, underlying diseases, current use of medications, previous GI history, and history of bowel function (regularity, consistency, and frequency). The patient with diarrhea may have frequent loose, watery stools, often with mild, cramping abdominal pain before bowel movements.

n Diagnosis

Determine if the patient has other problems relating to hydration or nutrition. Is the patient eating enough fiber? Are other medications or foods producing constipation? Does the patient need education to help in managing GI symptoms?

n Planning

Preparations with phenobarbital may be habit forming, so they should not be given to patients with a history of addiction. Initial doses should be small. These drugs should be used with caution in patients who have hepatic dysfunction or prostatic hypertrophy or who are at risk for glaucoma.

Opiates, loperamide, and diphenoxylate may cause psychologic or physical dependence if used in high dosages or for long periods. The nonspecific antidiarrheal agents provide symptomatic relief until the cause of the diarrhea can be determined and specific therapy can be instituted. These agents should not be used in patients with diarrhea caused by poisoning until the toxin has been removed from the GI tract.

n Implementation

Anticholinergics may be given orally or parenterally (when oral dosages cannot be retained or when immediate relief is needed). It is usually better to begin the oral dosage as soon as possible. All of the antidiarrheal agents are given orally; individual dosages are determined by need. Dietary changes are usually part of the treatment plan. The patient’s diet is restricted to clear liquids for 24 hours, and then foods are gradually added as tolerated.

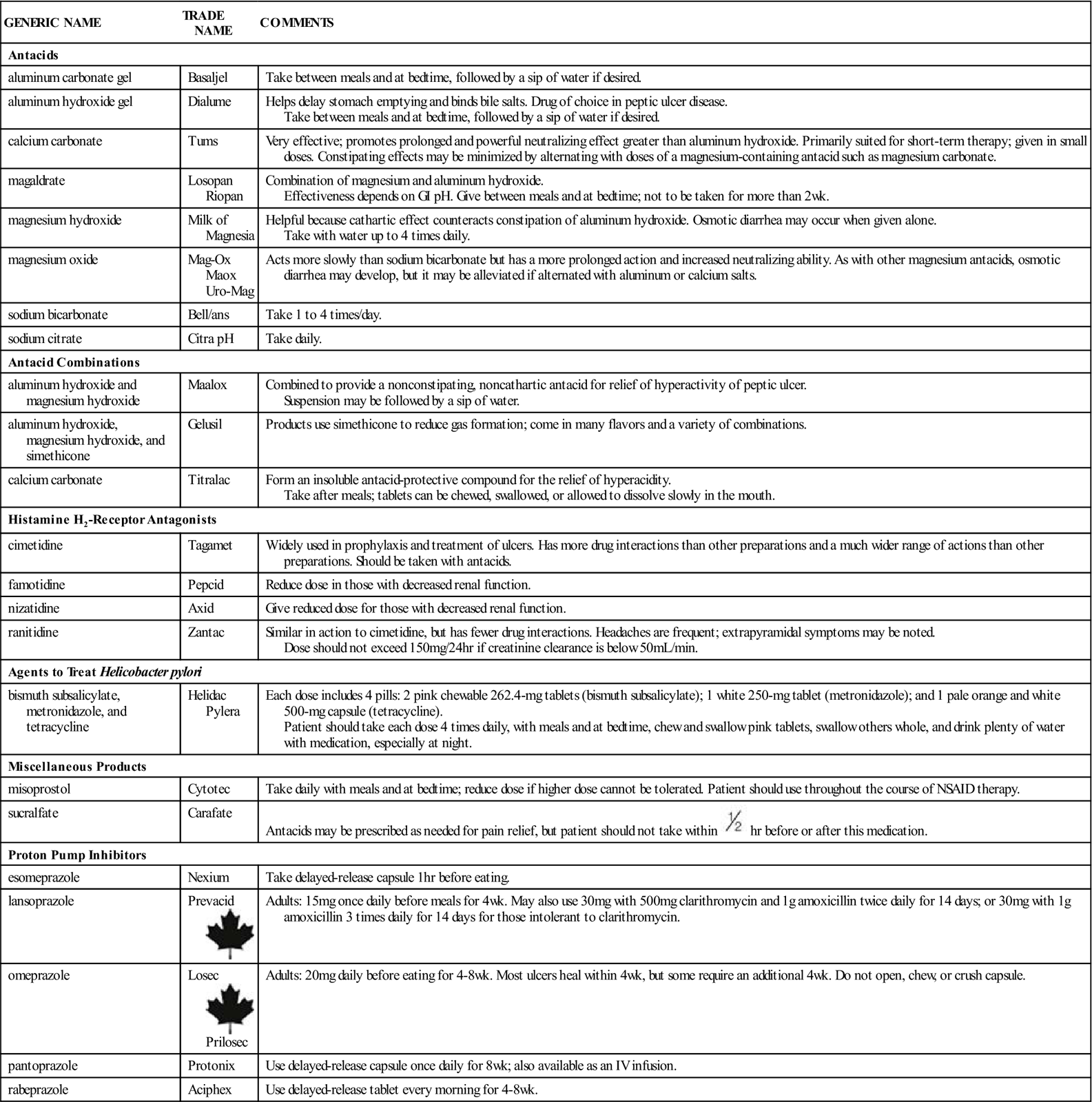

Table 19-2 gives a summary of anticholinergic, antispasmodic, and antidiarrheal medications. Synthetic forms of these anticholinergic drugs are more expensive than the natural forms (belladonna, atropine, and scopolamine).

![]() Table 19-2

Table 19-2![]()

Anticholinergic, Antispasmodic, and Antidiarrheal Medications

| GENERIC NAME | TRADE NAME | COMMENTS |

| Anticholinergics | ||

| Belladonna Alkaloids | ||

| atropine sulfate |

Sal-Tropine | Among the most effective of the anticholinergic drugs; minimal side effects. |

| belladonna tincture | Cystospaz | Used in adults and children. |

| l-hyoscyamine | Levsin | Reduces hypermotility and hyperacidity; several contraindications for use. Children: Dosage calculated based on weight. |

| scopolamine | Scopace | Similar to atropine in peripheral action, but parenteral dosages cause CNS depression, resulting in drowsiness, euphoria (excessive happiness), relief of fear, sleep, relaxation, and amnesia. May be given subcutaneously, IM, or through transdermal system, as well as PO. |

| Quaternary Anticholinergics | ||

| clidinium | Librax | Give daily before meals and at bedtime. |

| glycopyrrolate | Robinul | Used orally as adjunctive treatment in peptic ulcer disease. |

| mepenzolate | Cantil | Decreases gastric acid and pepsin secretion while slowing contractions of the colon. Give PO with meals and at bedtime. |

| methscopolamine | Pamine | Synthetic substitute for atropine as an antispasmodic. Give 30 min before eating and at bedtime. |

| propantheline | Pro-Banthine | Analogue to methantheline; more effective than methantheline in reduction of volume and acidity of stomach’s secretions. Give with meals and at bedtime; dosage adjusted according to therapeutic response. |

| Antispasmodics | ||

| dicyclomine | Antispas Bentyl Di-Spaz |

Synthetic antispasmodic controls spasms of the GI tract; also used in irritable bowel syndrome. Give PO or IM. |

| Anticholinergic Combination Drug | ||

| Hyoscyamine atropine scopolamine phenobarbital |

Donnatal | One of many combination products combining anticholinergic and sedative drugs. Because of the phenobarbital, these products may be habit forming. Individualize dose as needed and tolerated. Also comes as an Extentab. |

| Gastrointestinal Stimulant | ||

| metoclopramide | Reglan | Nocturnal heartburn related to GERD. Adults: Give 30 min before each meal and at bedtime for 2-8 wk; increase dosage if needed. |

| Antidiarrheals | ||

| bismuth subsalicylate | Bismatrol Pepto-Bismol |

Contains salicylates; ask patient about aspirin sensitivity. Has risk of producing Reye syndrome in children. May cause temporary darkening of the stool and tongue. Give PO every 30 min to 1 hr until symptoms are relieved or until a maximum of 8 doses have been given. Children: Dosage calculated by weight. Give with oral rehydration solution in children with severe diarrhea. |

| difenoxin with atropine | Motofen | Adults: 2 tablets, then 1 after each loose stool to a maximum of 8 tablets in 24 hr. |

| diphenoxylate and atropine sulfate | Lomotil Logen |

These are Schedule V controlled substances. Addition of atropine sulfate helps prevent abuse. Adults: 2 tablets or 2 teaspoonfuls 4 times daily until diarrhea is controlled. Children: Dosage calculated by weight. |

| kaolin and pectin | Kaopectate Parepectolin | Nonprescription products widely used in self-treatment of diarrhea; clinical effectiveness has not been established. Adults: Take 2 tablespoonfuls at once and 1 or 2 tablespoonfuls after each bowel movement. Children: Dosage calculated by weight. |

| lactobacillus | Bacid Lactinex |

Nonprescription product specifically used to treat diarrhea caused by antibiotics. Reestablishes normal intestinal flora and may be used prophylactically in patients with a history of antibiotic-induced diarrhea. Adults: Take 2 capsules or 4 tablets of Bacid; or use 1 packet of granules of Lactinex, 2 to 4 times daily, preferably with milk. |

| loperamide | Imodium | More potent drug with a longer duration of action with less CNS depression than diphenoxylate; now available OTC. Adults: Initial dose 4 mg PO, then 2 mg after each unformed stool; maximum of 16 mg PO daily. |

| mesalamine | Asacol Rowasa |

Used daily for 6 wk in ulcerative colitis. |

| olsalazine | Dipentum | Give PO in 2 divided doses for ulcerative colitis. |

| opium tincture (tincture of opium, paregoric) | Opium tincture contains 25 times the amount of morphine than Paregoric. Schedule III controlled substance. Given orally mixed with water. A white, milky fluid forms when they are mixed together. Tincture of opium Adults: Take 0.6 mL PO 4 times daily. Camphorated opium tincture (paregoric) Adults: Take 5-10 mL PO 4 times daily until diarrhea subsides. Children: Take 0.25-0.5 mL/kg PO 4 times daily until diarrhea subsides. |

|

| sulfasalazine | Azulfidine | Used for mild to moderate ulcerative colitis. Give in evenly divided doses. |

CNS, Central nervous system; IM, intramuscular; OTC, over the counter; PO, by mouth.![]() Indicates “Must-Know Drugs,” or the 35 drugs most prescribers use.

Indicates “Must-Know Drugs,” or the 35 drugs most prescribers use.

n Evaluation

Long periods of diarrhea can cause dehydration and electrolyte imbalance. Encourage the patient to increase fluid intake to replace the fluid lost in the stool.

Patients who are also taking diphenoxylate and atropine sulfate (Lomotil) or laxatives and narcotics should be watched for signs of central nervous system (CNS) depression. CNS side effects are rare with synthetic anticholinergic therapy, which is one of the advantages of the synthetic products.

Antidiarrheals should not be used on a long-term basis. Watch for diarrhea to decrease and to see if any adverse effects develop.

Long-term anticholinergic therapy may mask or alter the symptoms of GI disease, so it may be difficult to tell if GI disease has occurred again.

n Patient and Family Teaching

Laxatives

Overview

Laxatives are drugs that help draw fluid into the intestine to promote fecal softening, speed the passage of feces through the colon, and aid in the elimination of stool from the rectum. They are classified in five major categories, based on their mechanism of action. These categories are bulk-forming agents, fecal softeners, hyperosmolar or saline solutions, lubricants, and stimulant or irritant laxatives.

Laxatives are one of the major groups of drugs used by patients as self-treatment for constipation, with use increasing as patients age. Laxatives have a high rate of overuse, and they destroy the body’s natural emptying rhythm when they are used excessively. Laxatives are used in bowel training of individuals who have lost neurogenic control of the bowel, and are commonly used in preparing patients for x-ray, obstetric, or surgical procedures.

Action

Bulk-forming laxatives absorb water and expand, increasing both the bulk and the moisture content of the stool. The increased bulk stimulates peristalsis, and the absorbed water softens the stool. These agents do not have systemic effects.

Fecal softeners soften stool by lowering the surface tension, which allows the fecal mass to be softened by intestinal fluids. They also inhibit fluid and electrolyte reabsorption by the intestine.

Hyperosmolar laxatives such as lactulose and glycerin produce an osmotic effect in the colon by distending the bowel with fluid accumulation and promoting peristalsis and bowel movement. Saline laxatives also produce an osmotic effect by drawing water into the intestinal lumen of the small intestine and colon.

Lubricant laxatives create a barrier between the feces and the colon wall that prevents the colon from reabsorbing fecal fluid, thus softening the stool. The lubricant effect also eases the passage of feces through the intestine.

Stimulant or irritant laxatives increase peristalsis by several mechanisms, depending on the agent. These mechanisms include primary stimulation of colon nerves (senna preparations), stimulation of sensory nerves in the intestinal mucosa (bisacodyl), or direct stimulation of smooth muscle and inhibition of water and electrolyte reabsorption from the intestinal lumen (castor oil).

Uses

Bulk-forming laxatives are used in simple constipation and in atonic constipation, when the colon loses muscle tone as a result of overuse of other cathartics. Bulk-forming laxatives are also very useful in postpartum, older adult, and weakened patients. They have been used to treat diverticulosis and irritable bowel syndrome.

Fecal softeners help relieve constipation produced by a delay in rectal emptying. They are also useful when it is important to reduce straining at stool, such as in patients with hernia or cardiovascular disease, postpartum patients, or patients after rectal surgery.

Saline laxatives are used to cleanse the bowel in preparation for endoscopic or colonoscopic examination, x-ray studies, or surgery. They are used to hasten evacuation of worms after the administration of anthelmintics, and after the ingestion of poisons to help get rid of toxic material quickly. Lactulose and glycerin are most commonly used to treat simple constipation.

Lubricant laxatives are used to soften stool in conditions in which straining at stool should be avoided, such as in patients with myocardial infarction, aneurysm, stroke, or hernia or after abdominal or rectal surgery. They are also used to prevent discomfort and tearing or laceration of hemorrhoids or fissures.

Stimulant or irritant laxatives are used to treat constipation resulting from prolonged bed rest or poor dietary habits or constipation induced by other drugs. They are also used to cleanse the bowel in preparation for endoscopic or colonoscopic examination, x-ray studies, or surgery.

Adverse Reactions

Bulk-forming laxatives may produce abdominal cramps, diarrhea, strictures (narrowing), and obstructions (blockages) when taken without sufficient liquid. Nausea and vomiting are also common. Hypersensitivity may be demonstrated by development of asthma, dermatitis, rhinitis, and urticaria.

Fecal softeners may cause mild cramping or diarrhea.

Hyperosmolar or saline laxatives may produce abdominal cramping, nausea, and fluid and electrolyte disturbance if used daily or in patients with renal impairment. Hypermagnesemia may occur in patients with chronic renal insufficiency and is aggravated by increased intake of magnesium in hyperosmolar laxatives. In patients with cardiac disease or CHF, the increased sodium intake in the sodium-containing saline cathartics can start or worsen the condition.

Lubricant laxatives may produce abdominal cramps, vomiting, decreased absorption of nutrients and fat-soluble vitamins, diarrhea, and nausea. Lipid pneumonia caused by aspiration and deficiency syndromes resulting from low absorption of the fat-soluble vitamins may occur with long-term or excessive use.

Stimulant or irritant laxatives may produce muscle weakness (following excessive use of laxatives), dermatitis, pruritus, abdominal cramps, diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, alkalosis, and electrolyte imbalance (with excessive use).

Some patients believe they should have a bowel movement every day and may rely on laxatives to achieve this. Long-term or excessive use of stimulant laxatives may result in irritable bowel syndrome or a severe, prolonged diarrhea. These conditions may lead to hyponatremia and hypokalemia (decreased sodium and potassium in the blood) and dehydration. Cathartic colon, a syndrome resembling ulcerative colitis both radiologically and pathologically, may develop after chronic misuse.

Drug Interactions

Antibiotics, anticoagulants, digitalis preparations, and salicylates may have reduced effectiveness if used at the same time as bulk-forming agents because of binding and hindrance of absorption. A 2-hour interval between doses of these medications is required.

Fecal softeners should never be used along with mineral oil or other laxatives. The systemic absorption of other agents is enhanced, causing an increased laxative effect and greater risk of toxic effects, especially to the liver. Hyperosmolar saline laxatives should not be taken within 1 to 3 hours of tetracyclines, because they may form nonabsorbable complexes. Lubricant laxatives may reduce the effectiveness of anticoagulants, contraceptives, digitalis, and fat-soluble vitamins if taken together.

Antacids or milk should not be taken with bisacodyl tablets because together they cause the enteric coating to dissolve too rapidly, resulting in gastric irritation. Some laxatives cause rapid transit through the bowel, and so current use of many medications that require time to dissolve may be adversely affected.

Nursing Implications and Patient Teaching

Nursing Implications and Patient Teaching

n Assessment

Learn everything possible about the patient’s health history, including underlying disease, allergies, edema, or CHF; use of a sodium-restricted diet; and other drugs being taken. The patient should be evaluated for potential abuse. Constipation that persists should always be evaluated for serious organic causes. Changes in bowel habits, especially waking up at night to defecate, should always be investigated.

The patient may complain of increased hardness of stool or of difficulty in passing stool. Decreased frequency of stools, mild abdominal discomfort and distention, and occasionally mild anorexia may be present. Confused geriatric patients may show only increased restlessness when they are constipated.

Laxatives should not be given to patients with abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, other signs of appendicitis, or acute surgical abdominal conditions. Other contraindications include fecal impaction, intestinal ulcerations, stenosis or obstruction, disabling adhesions, or dysphagia.

n Diagnosis

What are the factors that have caused constipation? Does the patient have other problems in terms of hydration, lack of nutritional fiber, or eating disorders that underlie the development of constipation? Is the patient taking codeine, morphine, or other opioids that may cause constipation?

n Planning

Many bulk-forming products contain significant amounts of dextrose, galactose, and sucrose and should be avoided in patients with diabetes mellitus. Allergic reactions (urticaria, rhinitis, and asthma) may occur as a result of the plant gums present in these agents. This should be considered in patients with a history of allergic reactions, especially to plants.

Bulk-forming agents may become dry, thick, and hardened in the throat or within the intestine if they are swallowed without sufficient water. They can cause esophageal or intestinal obstruction or impaction if this occurs. The drugs should never be chewed or swallowed without one or more full glasses of water. Before giving medication for constipation, ensure that the patient is well hydrated (has enough fluids).

Products with sodium salt should be avoided in patients with edema, pregnancy, CHF, and sodium-restricted diets. Potassium salt should be avoided in patients with renal impairment. Because laxatives are available without prescription, it is especially important to teach the patient about these serious side effects.

Begin educating the patient by explaining the usefulness of exercise, diet, and liquids to reduce constipation. The patient should be taught to eat bulk-forming foods, fruits, vegetables, and whole-grain cereals and encouraged to perform more physical activities if able to do so. Proper bowel habits should be discussed and encouraged, and increased fluid intake should be stressed.

Overdosage or overuse of stimulant laxatives may cause excessive fluid loss and electrolyte imbalance, particularly hypokalemia. Overuse of any laxative can lead to atonic constipation and create dependence on the laxative.

If the patient does not really need a laxative, or must use a laxative because of constipation resulting from pain medication, the bowel must be retrained to function without laxative use. Good hydration, high fiber intake, and exercise all help patients make this change.

n Implementation

All bulk-forming and stimulant laxatives are given orally with one or more glasses of liquid. Most other laxatives are available for oral administration or as enemas.

Plan medication administration to allow the drug’s effects to occur at a time that will not interfere with the patient’s rest or digestion. Administration of lubricant laxatives should be timed so that they are not given within 2 hours of meals or medication.

Bisacodyl enteric-coated tablets must be swallowed whole, never chewed or crushed, and never taken with milk or antacids.

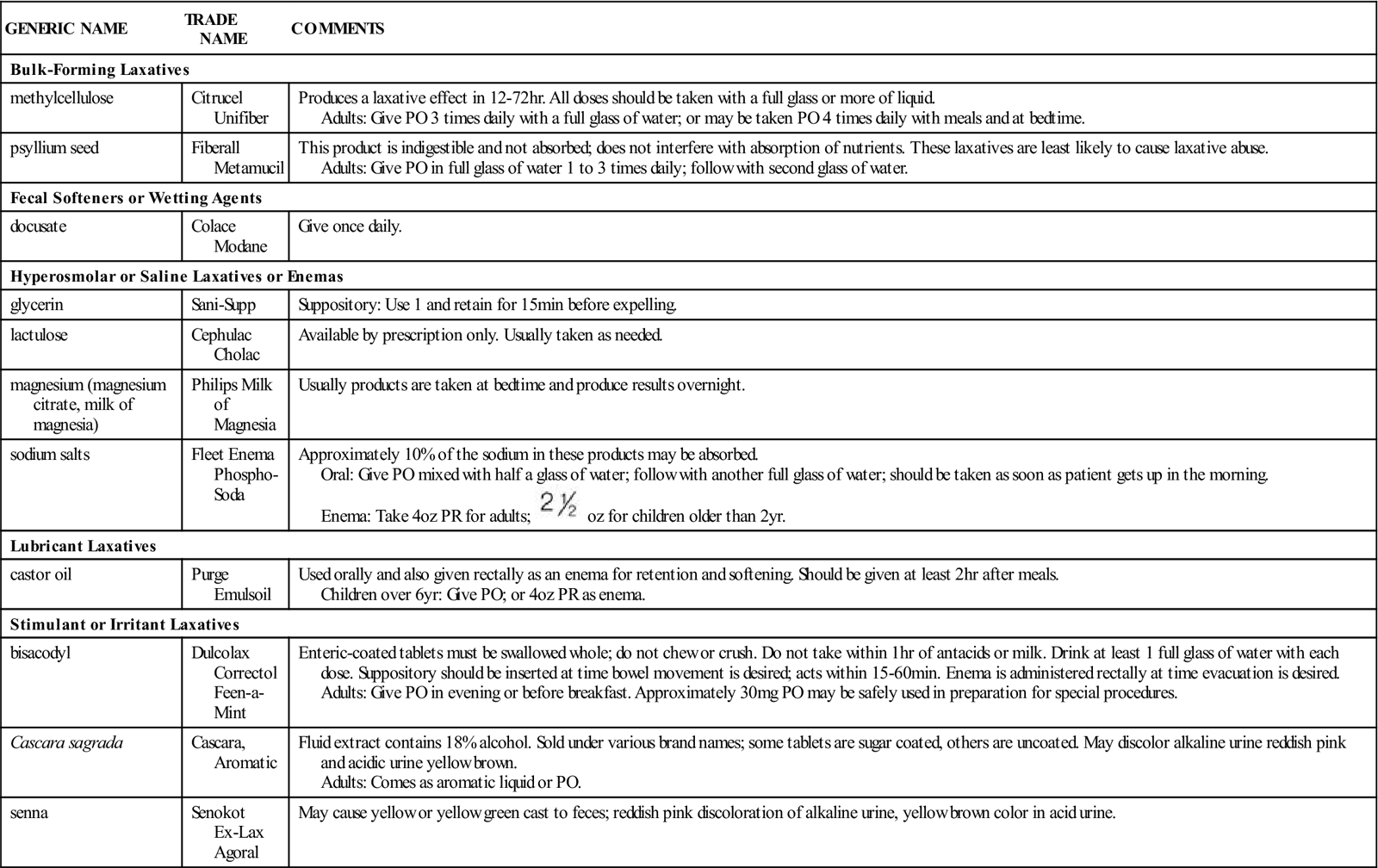

A summary of laxative products is given in Table 19-3. The need for mixtures of laxatives has not been documented. The actions of various laxatives show that combinations are unnecessary and may produce harmful or undesirable effects. They also tend to be more expensive than drugs sold individually. A partial listing of some of the available drug mixtures that patients may ask the nurse about is provided in Table 19-4, but it is not recommended that combination drugs be used.

![]() Table 19-3

Table 19-3

| GENERIC NAME | TRADE NAME | COMMENTS |

| Bulk-Forming Laxatives | ||

| methylcellulose | Citrucel Unifiber | Produces a laxative effect in 12-72 hr. All doses should be taken with a full glass or more of liquid. Adults: Give PO 3 times daily with a full glass of water; or may be taken PO 4 times daily with meals and at bedtime. |

| psyllium seed | Fiberall Metamucil |

This product is indigestible and not absorbed; does not interfere with absorption of nutrients. These laxatives are least likely to cause laxative abuse. Adults: Give PO in full glass of water 1 to 3 times daily; follow with second glass of water. |

| Fecal Softeners or Wetting Agents | ||

| docusate | Colace Modane |

Give once daily. |

| Hyperosmolar or Saline Laxatives or Enemas | ||

| glycerin | Sani-Supp | Suppository: Use 1 and retain for 15 min before expelling. |

| lactulose | Cephulac Cholac |

Available by prescription only. Usually taken as needed. |

| magnesium (magnesium citrate, milk of magnesia) | Philips Milk of Magnesia | Usually products are taken at bedtime and produce results overnight. |

| sodium salts | Fleet Enema Phospho-Soda |

Approximately 10% of the sodium in these products may be absorbed. Oral: Give PO mixed with half a glass of water; follow with another full glass of water; should be taken as soon as patient gets up in the morning. Enema: Take 4 oz PR for adults;  oz for children older than 2 yr. oz for children older than 2 yr. |

| Lubricant Laxatives | ||

| castor oil | Purge Emulsoil |

Used orally and also given rectally as an enema for retention and softening. Should be given at least 2 hr after meals. Children over 6 yr: Give PO; or 4 oz PR as enema. |

| Stimulant or Irritant Laxatives | ||

| bisacodyl | Dulcolax Correctol Feen-a-Mint |

Enteric-coated tablets must be swallowed whole; do not chew or crush. Do not take within 1 hr of antacids or milk. Drink at least 1 full glass of water with each dose. Suppository should be inserted at time bowel movement is desired; acts within 15-60 min. Enema is administered rectally at time evacuation is desired. Adults: Give PO in evening or before breakfast. Approximately 30 mg PO may be safely used in preparation for special procedures. |

| Cascara sagrada | Cascara, Aromatic | Fluid extract contains 18% alcohol. Sold under various brand names; some tablets are sugar coated, others are uncoated. May discolor alkaline urine reddish pink and acidic urine yellow brown. Adults: Comes as aromatic liquid or PO. |

| senna | Senokot Ex-Lax Agoral |

May cause yellow or yellow green cast to feces; reddish pink discoloration of alkaline urine, yellow brown color in acid urine. |

![]() Table 19-4

Table 19-4

| TRADE NAME | CHEMICAL COMBINATION |

| Peri-Colace | casanthranol, docusate sodium |

| Senokot-S | senna, docusate sodium |

n Evaluation

Laxatives should be used only for short periods and should not require any patient monitoring. If for any reason they are used on a long-term basis, ask the patient about bowel habits, diet, and exercise, and monitor for adverse reactions. Many of the stimulant laxatives discolor alkaline urine reddish pink and acidic urine yellow brown. They may give a reddish color to feces.

n Patient and Family Teaching

Miscellaneous Gastrointestinal Drugs

Overview

Many diseases and symptoms affect the GI tract; there are also many drugs used in their treatment. Antiflatulents, such as simethicone, break up GI gas bubbles through a defoaming action so they may be more easily expelled by belching or as flatus. Pancreatic digestive enzymes are used as replacement therapy for individuals with pancreatic enzyme insufficiency. Emetics are used mostly in emergency situations to produce vomiting by direct action on the vomiting center. Chenodiol acts on the liver to increase breakdown of radiolucent cholesterol gallstones. Disulfiram is used in alcoholic patients to produce a severe sensitivity to alcohol. Each of these drugs is briefly described.

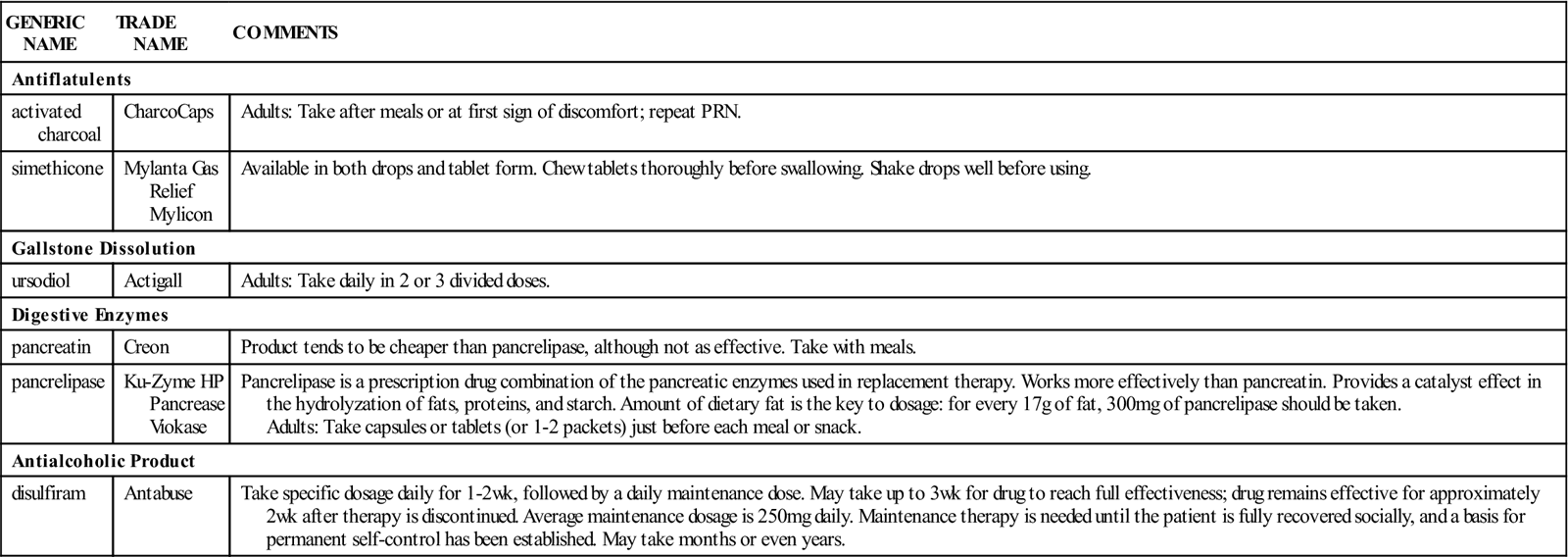

Table 19-5 summarizes the important miscellaneous GI medications.

![]() Table 19-5

Table 19-5

Miscellaneous Gastrointestinal Medications

| GENERIC NAME | TRADE NAME | COMMENTS |

| Antiflatulents | ||

| activated charcoal | CharcoCaps | Adults: Take after meals or at first sign of discomfort; repeat PRN. |

| simethicone | Mylanta Gas Relief Mylicon | Available in both drops and tablet form. Chew tablets thoroughly before swallowing. Shake drops well before using. |

| Gallstone Dissolution | ||

| ursodiol | Actigall | Adults: Take daily in 2 or 3 divided doses. |

| Digestive Enzymes | ||

| pancreatin | Creon | Product tends to be cheaper than pancrelipase, although not as effective. Take with meals. |

| pancrelipase | Ku-Zyme HP Pancrease Viokase |

Pancrelipase is a prescription drug combination of the pancreatic enzymes used in replacement therapy. Works more effectively than pancreatin. Provides a catalyst effect in the hydrolyzation of fats, proteins, and starch. Amount of dietary fat is the key to dosage: for every 17 g of fat, 300 mg of pancrelipase should be taken. Adults: Take capsules or tablets (or 1-2 packets) just before each meal or snack. |

| Antialcoholic Product | ||

| disulfiram | Antabuse | Take specific dosage daily for 1-2 wk, followed by a daily maintenance dose. May take up to 3 wk for drug to reach full effectiveness; drug remains effective for approximately 2 wk after therapy is discontinued. Average maintenance dosage is 250 mg daily. Maintenance therapy is needed until the patient is fully recovered socially, and a basis for permanent self-control has been established. May take months or even years. |

Antiflatulents

Action

Simethicone is an antiflatulent that breaks up and prevents mucus-surrounded pockets of gas from forming in the intestine. Mucus surrounding the gas bubbles is broken down, and the gas bubbles all come together, freeing the gas. Gastric pain is then reduced. Charcoal is occasionally used as an antiflatulent but is used primarily in the treatment of drug overdosage to absorb chemicals.

Uses

Antiflatulents are used to treat problems that produce bloating, flatulence, or postoperative gas pains. They may also be used for chronic air swallowing, functional dyspepsia (stomach discomfort after eating), peptic ulcer, spastic or irritable colon, and diverticulitis. The patient may complain of being bloated or distended, of feeling “full” or gaseous, or of frequent belching. Gas pains may also be noted, especially after surgery. Determine if the flatulence is caused by food and whether changing the diet may decrease the symptoms. Antiflatulents are often used together with antacid therapy. This medication is intended for short-term use only. More rigorous evaluation should be undertaken if symptoms do not disappear with therapy.

Gallstone-Solubilizing Agents

Action

Gallstone-solubilizing agents act on the liver to suppress cholesterol and cholic acid synthesis. Biliary cholesterol desaturation is enhanced, and breakup or dissolution of radiolucent cholesterol gallstones (those that allow x-rays to pass through and thus show up as dark images) eventually occurs. There is no effect on calcified or radiopaque gallstones (those that absorb x-rays and thus show up as white images) or radiolucent bile pigment stones.

Uses

Gallstone-solubilizing agents are useful in selected patients with radiolucent stones in gallbladders that opacify well (show up when dye is used). These patients are poor surgical risks because of disease or advanced age. Success is likely to be higher with small stones that float.

Adverse Reactions

Adverse reactions to gallstone-solubilizing agents may include dose-related diarrhea, anorexia, constipation, cramps, dyspepsia, epigastric distress, flatulence, heartburn, nausea, nonspecific abdominal pain, and vomiting. Laboratory test results may be altered; nonspecific decreases in white cell count may also develop.

Drug Interactions

Biliary cholesterol secretion and gallstones may be increased by estrogens, clofibrate, and oral contraceptives. Therefore these drugs may counteract the effectiveness of gallstone-solubilizing agents. Bile acid–sequestering agents such as cholestyramine and colestipol may reduce the absorption of gallstone-solubilizing agents. Aluminum-based antacids may absorb bile acids and also reduce the absorption of gallstone-solubilizing agents.

These medications should not be used in patients with known liver or other gallbladder disease. If the gallbladder fails to show up after two consecutive single doses of dye, or if radiopaque or radiolucent bile pigment stones are seen, these medications will likely not be used. These products may produce hepatotoxicity (damage to the liver), ranging from mild toxicity to fatal hepatic failure. They should be used only in patients without previous hepatic problems, and careful monitoring of the patient’s liver function is required. There is also the chance that chenodiol therapy might contribute to the development of colon cancers in individuals who are predisposed to develop them.

If diarrhea develops, reducing the dosage usually eliminates the symptoms. The patient is often able to resume higher dosages without diarrhea occurring again.

Evaluation of patient compliance is important. The patient must be reliable in keeping appointments, reporting problems, and having periodic health evaluations.

Digestive Enzymes

Action

Pancreatic digestive enzymes promote digestion by acting as replacement therapy when the body’s natural pancreatic enzymes are lacking, not secreted, or not properly absorbed. They are made from pork pancreas. Healthy patients may find intestinal gas is decreased when they take the medication.

Uses

Digestive enzymes are often indicated for individuals with poor digestion, for predigestive purposes, and as replacement therapy. They may be used to relieve the symptoms of cystic fibrosis, cancer of the pancreas, or chronic inflammation of the pancreas causing malabsorption syndromes. Patients who have had GI bypass surgery may also be helped. Obstruction of the pancreatic or common bile duct by a tumor may produce a need for these enzymes.

Adverse Reactions

If a proper dietary balance of fat, protein, and starch is not maintained, temporary indigestion may develop. Nausea, abdominal cramps, and diarrhea have been reported in patients taking high doses. Inhalation of the powder may provoke asthma.

Drug Interactions

Antacids containing calcium carbonate or magnesium hydroxide may cancel out the therapeutic effect of digestive enzymes. In addition, serum iron levels produced by iron supplements may be decreased by these enzymes.

Nursing Implications and Patient Teaching

Nursing Implications and Patient Teaching

The patient may complain of sudden, intense pain in the gastric region; hiccups; belching of gas; vomiting; constipation; pain radiating to the back; weakness; diarrhea; indigestion; ravenous appetite without weight gain; and chronic cough and infections.

Patients who are hypersensitive to pork protein should avoid this therapy. The patient should avoid breathing the powdered form of the enzymes or allowing it to come into contact with the skin, because it may produce irritation.

Digestive enzymes are given with meals or snacks. They are available in tablet or capsule form, which is swallowed, not chewed. They also come in a powder, or the capsules may be opened and sprinkled on food for those who have difficulty swallowing tablets. Medication granules are not to be taken without food, because this will destroy the enzymes.

The correct dosage can be determined after several weeks of therapy. Different flavors are available for this medication.

Monitor the patient for the therapeutic effect and the absence of adverse reactions. Question the patient about the appearance of stools, because this may help evaluate the degree of malabsorption present.

n Patient and Family Teaching

Disulfiram

Action

Disulfiram (Antabuse) produces a severe sensitivity to alcohol that results in a very unpleasant reaction. This disulfiram reaction includes severe nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea, as well as many other adverse reactions, when even small amounts of alcohol are swallowed. This drug causes excessive amounts of acetaldehyde to develop by stopping the normal liver enzyme activity after the conversion of alcohol to acetaldehyde. Increased levels of acetaldehyde produce the disulfiram reaction. The reaction is present until the alcohol is completely metabolized. The intensity of the reaction is variable, but it is usually related to the amount of disulfiram and alcohol swallowed.

Uses

Disulfiram (Antabuse) is used only for the management of alcoholism. It is used to discourage alcohol intake, which in turn forces the patient to be sober. This drug is used in addition to psychiatric therapy or alcohol counseling and in patients who are motivated and fully cooperative.

Adverse Reactions

Disulfiram may produce drowsiness, fatigue, headache, optic neuritis (with impaired vision, decreased color perception, and blindness), psychotic reactions, restlessness, acneiform eruptions, dry mouth, elevation of serum liver enzyme levels, hepatotoxicity, metallic or garlic-like aftertaste, and impotence.

Drug Interactions

Use of disulfiram with even small amounts of alcohol produces a severe reaction. When used together, disulfiram increases the effects of anticoagulants, phenytoins, and barbiturates, and may increase the side effects of isoniazid. Use with metronidazole and marijuana has an additive effect and may produce psychotic episodes. Exaggerated clinical effects of diazepam and chlordiazepoxide are produced when these drugs are taken at the same time as disulfiram. Use with paraldehyde may produce the disulfiram-alcohol reaction.

Some medications, such as metronidazole, produce a similar reaction when taken with alcohol. Patients must be warned of these disulfiram-like reactions.

Nursing Implications and Patient Teaching

Nursing Implications and Patient Teaching

Disulfiram should not be used if the patient has consumed alcohol in any form within the last 12 hours. This includes the use of cough mixtures, tonics, vanilla, vinegar, some sauces, aftershave lotions, back-rubbing solutions, some creams, or other products containing alcohol. Do not use disulfiram if there has been recent ingestion of paraldehyde or metronidazole. Do not use in the presence of severe myocardial disease or coronary occlusion, psychoses, or hypersensitivity (allergy) to disulfiram. Do not use disulfiram in pediatric patients.

Disulfiram should be used with extreme caution in patients with any of the following conditions: diabetes mellitus, epilepsy, cerebral damage, hypothyroidism, chronic and acute nephritis, hepatic cirrhosis or insufficiency, conditions requiring multiple drug usage, coronary artery disease, and hypertension. In these patients, there is the possibility of an accidental disulfiram reaction.

The patient should give permission for disulfiram therapy. The patient and a responsible family member need to understand the consequences of this therapy. Disulfiram reactions may occur for up to 2 weeks after a single dose of disulfiram. The longer patients take this drug, the more sensitive they will become to alcohol. The disulfiram reaction may be provoked by even small amounts of alcohol. The patient should be cautioned against hidden forms of alcohol (tonics, cough syrups, aftershave lotions).

Disulfiram users should wear a MedicAlert bracelet or necklace or carry a medical identification card indicating that they use this drug and describing the symptoms most likely to occur in the disulfiram reaction. Cards to give to patients taking this drug may be obtained from the drug company.

The patient should be actively involved in support and counseling to reduce psychologic dependence and should be monitored for compliance and development of adverse effects.

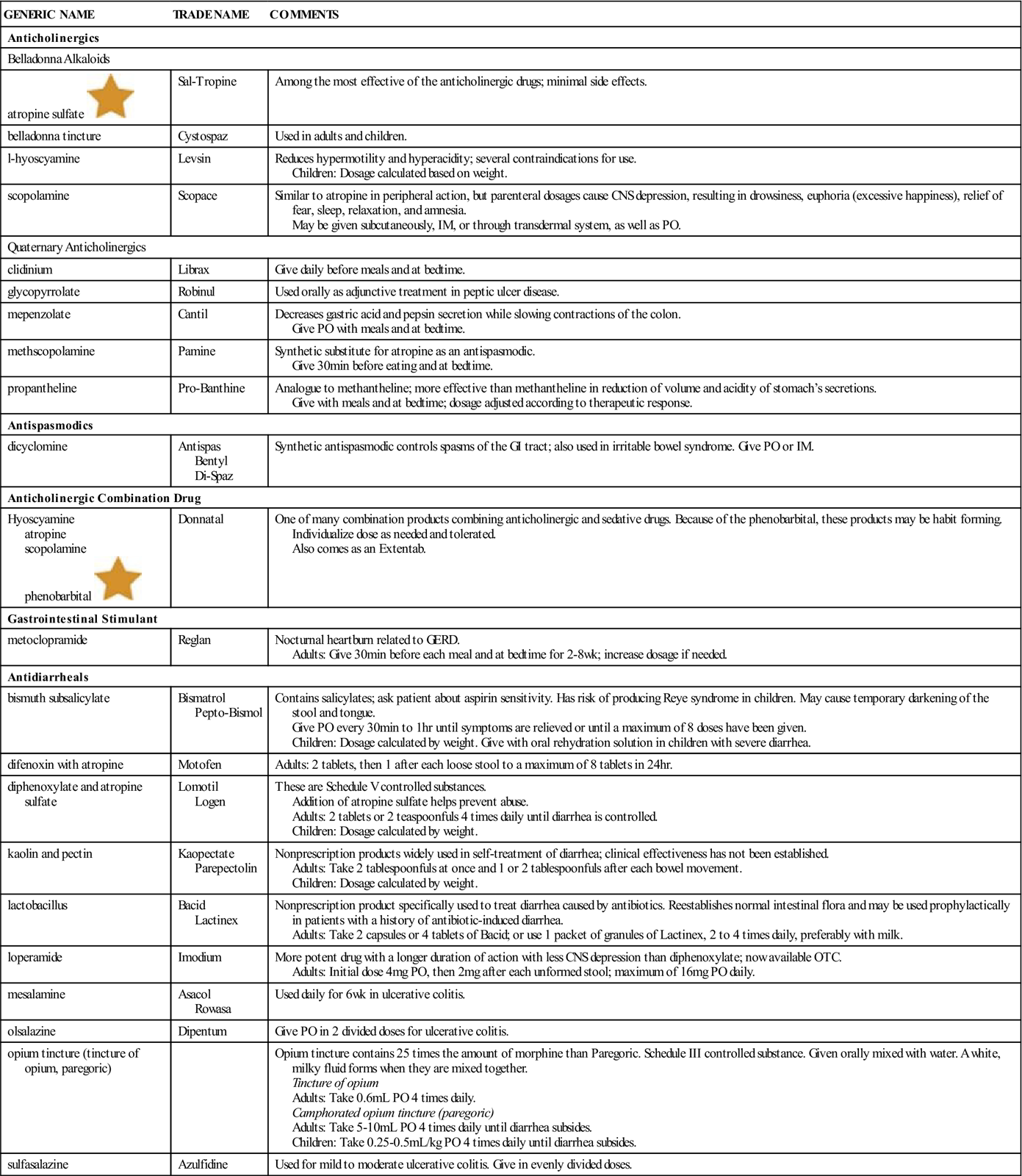

Complementary and Alternative Therapies

The Complementary and Alternative Therapies box describes herbal preparations commonly used by patients and potential drug interactions with other medications.