CHAPTER 19. BOWEL OBSTRUCTION

Debra E. Heidrich and Pamela Sue Spencer

DEFINITION AND INCIDENCE

Bowel obstruction is defined as abnormally delayed or blocked transit through the intestinal tract (Ripamonti & Mercadante, 2004; Waller & Caroline, 2000). With obstruction, the motor activities of the small intestine and/or colon, characterized by contractile patterns that serve the requirements of each organ, become impaired (Hasler, 2003). Although not a frequent complication, bowel obstruction occurs more often in the palliative care patient than in patients in other care settings. Malignant bowel obstruction (MBO) occurs in approximately 3% of all patients with cancer, but up to 24% of patients with colon cancer and up to 42% of women with ovarian cancer may develop obstructions (Hirst & Regnard, 2003; Ripamonti & Mercadante, 2004). Less frequently, MBOs are seen with cancers of the pancreas, stomach, endometrium, bladder, and prostate (Waller & Caroline, 2000). One retrospective chart audit showed that 19% of patients with malignant small bowel obstruction also had a large bowel obstruction (Miller, Boman, Shrier et al., 2000). Bowel obstructions are most frequently caused by postoperative adhesions, occurring in about 3.5% of people who have intestinal resection (Dang, Aguilera, Dang et al., 2002; Fazio, Cohen, Fleshman et al., 2006; Ryan, Wattchow, Walker et al., 2004). The incidence of other nonmalignant causes of bowel obstruction is not as well documented. Bowel obstructions may involve the small or large bowel and can be partial or complete. Any site of the gastrointestinal tract may be involved, from the gastroduodenal junction to the rectum and anus (Hirst & Regnard, 2003).

ETIOLOGY AND PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

MBO may be intraluminal due to tumors blocking the bowel, intramural due to tumor infiltration of the intestinal muscles and the accompanying inflammation that occludes bowel, or extramural due to tumors outside the lumen that compress the bowel wall (Davis & Nouneh, 2000; Hirst & Regnard, 2003; Ripamonti & Mercadante, 2004). Adhesions may contribute to malignant obstruction in people who have had previous abdominal surgery (Miller et al., 2000). In addition, patients with cancer may have motility disorders from malignant involvement of intestinal muscle or autonomic nerves. Nonmalignant causes of bowel obstruction include adhesions from previous surgery, incarcerated or strangulated hernias, pseudo-obstruction, and fecal impaction.

Improperly managed constipation may lead to impaction and symptoms of bowel obstruction (Pappagallo, 2001; Ripamonti & Mercandante, 2004). Constipation is a common problem in people with advanced illnesses due to decreased food and fluid intake and decreased mobility. This problem is compounded by the use of medications that contribute to constipation, such as opioids and anticholinergic drugs. An impaction is easily misdiagnosed as clinicians mistake hard abdominal masses of feces for tumors (Hirst & Regnard, 2003).

Pseudo-obstruction presents like a mechanical obstruction but has no anatomic cause (Sutton, Harrell, & Wo, 2006). It is sometimes called adynamic ileus and is defined as a state of inhibited motility in the gastrointestinal tract that may be temporary (reversible) or permanent (Summers, 2003). Although there are many potential causes of pseudoobstruction, the incidence is believed to be rare (Smith, Williams, & Ferris, 2003). In the palliative care setting, the more likely causes of pseudo-obstruction include the following:

▪ Collagen vascular disease, such as scleroderma

▪ Primary muscle disease, such as any type of muscular dystrophy

▪ Endocrine disorders, including diabetes

▪ Neurological disorders, including Parkinson’s disease and paraneoplastic syndromes (e.g., Eaton-Lambert myasthenic syndrome)

▪ Medications, including opioids, tricyclic antidepressants, phenothiazines, clonidine, antiparkinsonian medications, anticholinergic drugs, and vinca alkaloid chemotherapy agents

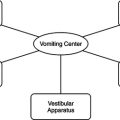

When the bowel is obstructed, intestinal contents accumulate proximal to the blockage and the bowel distends. Bowel activity increases in an effort to restore peristalsis, leading to uncoordinated muscle contractions, increased intestinal secretions, and increasing bowel distention. Further, the bacterial flora of the bowel contents increases above normal levels, causing gas production and, again, increasing bowel distention. The increased pressure on the cell walls initiates the inflammatory process, resulting in even more edema and secretions. Hypoxia of the tissues develops as the increased pressure interferes with venous drainage and oxygenation. Death results when third-spacing of fluid causes hypovolemia and renal failure, when the passage of toxins from the intestine into the lymphatics and circulation leads to sepsis, or when these events occur together (Ripamonti & Mercadante, 2004).

Obstructions in the proximal bowel cause vomiting and severe dehydration and electrolyte disturbances but minimal distention. Blockage in the distal bowel causes a large amount of fluid to accumulate in the bowel, third-spacing of fluids and dehydration, abdominal distention, and feculent vomiting (Dang et al., 2002; Hirst & Regnard, 2003). Malignant obstructions may present acutely but are more likely to have a gradual onset over weeks or months (Hirst & Regnard, 2003).

ASSESSMENT AND MEASUREMENT

The assessment of bowel obstruction is based primarily on the presenting symptoms of pain, vomiting, and obstipation (Dang et al., 2002). Abdominal pain is present in about 90% of patients presenting with a bowel obstruction (Hirst & Regnard, 2003). The pain is usually described as colicky, meaning it worsens when the intestines contract in their attempt to restore peristalsis but lessens when the muscles relax. Pain usually presents in the suprapubic region when the obstruction is low in the colon (Waller & Caroline, 2000). As the distention worsens, so does the pain; it may become constant. Assessment measures include noting the onset, location, and severity of pain, noting whether the pain is intermittent or continuous, and noting any worsening of the pain over time.

Because there is less distention with proximal obstructions (e.g., jejunal or small bowel obstructions), there may be less pain but significantly more vomiting. Vomiting develops later in obstructions of the distal ileum and colon and may be feculent (Dang et al., 2002; Hirst & Regnard, 2003). Assess the amount, color, and odor of emesis. Remember that some patients may have concurrent large and small bowel obstructions.

Dehydration is a concern with high-volume emesis and poor intake, so assessment must include evaluation of hydration status. Assess skin turgor, blood pressure, heart rate, urinary output, and subjective symptoms of dehydration, such as headache and dry mouth.

While patients with complete bowel obstruction are usually obstipated, those with partial or intermittent bowel obstructions may have constipation or diarrhea. Ask about frequency, amount, and consistency of bowel movements. Be aware that what is reported as diarrhea may be overflow of liquefied fecal material (Waller & Caroline, 2000).

Abdominal obstruction can also compromise respiratory function due to pressure on the diaphragm secondary to abdominal distention. Patients with cardiorespiratory problems at baseline are especially vulnerable (Summers, 2003). Assess changes in respiratory rate and effort, as well as any report of dyspnea.

HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

The diagnosis of bowel obstruction can present challenges for the clinician. Some patients advance from a partial to complete occlusion in an insidious manner, whereas other patients may develop an intermittent obstruction, causing fluctuating symptoms. It is essential that clinicians complete a detailed history, including:

▪ History of any gastrointestinal disease or surgery (note that this may be unrelated to the terminal illness)

▪ History of muscular, neurological, endocrine, or collagen disorders that may affect the bowel

▪ History of receiving a vinca alkaloid chemotherapeutic agent

▪ Usual bowel patterns and any changes in bowel patterns

▪ Onset, location, intensity, and duration of pain as well as how the pain has changed over time

▪ Onset, frequency, and amount of emesis

▪ Food and fluid intake

▪ Amount, frequency, and concentration of urine

▪ Subjective signs of dehydration, especially headache, dizziness, or dry mouth

▪ Review of all medications, noting those that stimulate the gastrointestinal system, such as laxatives and metoclopramide, as well as those that may decrease peristalsis, like opioids, tricyclic antidepressants, and anticholinergic drugs

A comprehensive physical examination includes assessing the patient’s general appearance, signs of hydration, fever, hypotension, and respiratory compromise. Perform a thorough assessment of the abdomen. Note any laparotomy scars or abdominal distention. Palpate for masses, noting that a fecal impaction can be mistaken for a tumor. Note any tenderness to palpation. Listen to bowel sounds. In early bowel obstruction, bowel sounds may be high pitched and tinkling. Be aware, however, that classic tinkling sounds are actually rare (Twycross & Wilcock, 2001). Bowel sounds may be absent with complete bowel obstruction. Complete a rectal examination to assess rectal tone and the presence of masses, fecal impaction, or liquid stool.

DIAGNOSTICS

When the clinical evaluation suggests obstruction or ileus, radiographic examination is helpful to confirm the diagnosis, differentiate ileus from obstruction, or, at least, contribute to an understanding of the cause (Jenkins, Taylor, & Behrns, 2000). In patients in the end stage of advanced cancer, abdominal films are indicated only when the patient may be a candidate for palliative surgery to relieve the obstruction or to distinguish between mechanical obstruction and severe constipation (Waller & Caroline, 2000). Multislice spiral computed tomography, computed tomography colonography, and magnetic resonance imaging are more accurate than plain radiographs and can determine the extent of intraabdominal cancer, an important factor in determining if a patient is a surgical candidate (Low, Chen, & Barone, 2003; Taourel, Kessler, Lesnick et al., 2003). In addition to radiographic studies, blood chemistries may be obtained to evaluate fluid and electrolyte status.

INTERVENTIONS AND TREATMENT

Treatment decisions should be based on the patient’s predicted disease trajectory, current condition, and obstructive involvement. Surgical intervention is the primary approach to the management of bowel obstruction in the general hospital setting. All patients should be evaluated for surgery since those who have surgery are less likely to experience a re-obstruction than are those whose bowel obstructions are managed nonoperatively (Miller et al., 2000). However, many patients with advanced diseases are not good surgical candidates. Also, Miller and colleagues (2000) reported a postoperative morbidity rate of 67% and mortality rate of 13% in patients with MBO. Because of the high morbidity and mortality associated with surgery, it is recommended that a 5-day trial of pharmacological intervention be initiated before considering surgery; if the obstruction does not resolve with pharmacological intervention, then surgery may be an option for the appropriately selected patient (Miller et al., 2000). Factors associated with a poor prognosis with surgery are listed in Box 19-1.

Box 19-1

Oxford University Press

ABSOLUTE CONTRAINDICATIONS

Intraperitoneal carcinomatosis with intestinal motility problems

Ascites

Widespread, palpable abdominal masses

Multiple partial bowel obstruction

Previous abdominal surgery that showed diffuse metastatic disease

Involvement of the proximal stomach

RELATIVE CONTRAINDICATIONS

Poor performance status

Patients over 65 years old with cachexia

Previous radiation therapy to the abdomen or pelvis

Low serum albumin

Distant metastasis, pleural effusion, or pulmonary metastasis

Elevated blood urea nitrogen or alkaline phosphatase levels

Adapted from Ripamonti, C. & Mercadante, S. (2004). Pathophysiology and management of malignant bowel obstruction. In D. Doyle, G. Hanks, N. Cherny, & K. Calman (Eds.). Oxford textbook of palliative medicine (3rd ed., pp. 496-506). New York: Oxford University Press.

Pharmacological management of bowel obstruction is recommended to control symptoms in patients who are not good surgical candidates and to improve the condition of the bowel in those being prepared for surgery (Mercadante, Ferrera, Villari et al., 2004). One study of 15 patients demonstrated that the combination of metoclopramide 60 mg/day, octreotide 0.3 mg/day, and dexamethasone 12 mg/day, given as a continuous subcutaneous infusion, led to recovery of intestinal transit within 1 to 5 days and resolution of vomiting within 24 hours (Mercadante et al., 2004). It is proposed that these medications are an effective combination because of the antiemetic and prokinetic effects of metoclopramide, the antisecretory effect of octreotide (decreases intestinal secretions contributing to bowel distention), and the antiinflammatory effect of dexamethasone (decreases intestinal wall edema).

Opioids may be given to treat the abdominal pain. In addition, anticholinergic medications, such as glycopyrrolate or hyoscine butylbromide, may be helpful for colicky pain due to their ability to relax smooth muscle (Davis & Nouneh, 2000; Hirst & Regnard, 2003; von Gunten & Muir, 2002). In the presence of complete obstruction, stimulant laxatives may exacerbate pain and should be discontinued.

Metoclopramide, as mentioned, is a good antiemetic and increases gastrointestinal motility. Increased gastrointestinal motility may be especially helpful if the patient has a partial obstruction or if a motility disorder caused or contributed to the obstruction. As with stimulant laxatives, in complete obstruction, this stimulation may worsen colicky pain and metoclopramide should be discontinued (Hirst & Regnard, 2003; von Gunten & Muir, 2002). Haloperidol is another good medication for nausea and vomiting (Davis & Nouneh, 2000; Hirst & Regnard, 2003; von Gunten & Muir, 2002). Dexamethasone may be included in the plan of care for its antiemetic and antiinflammatory properties.

As discussed, octreotide decreases the amount of gastrointestinal secretions. It may be used alone or in combination with anticholinergic agents such as scopolamine to decrease distention, pain, cramping, nausea, and vomiting (Cowan & Palmer, 2002; Mercandante, Ripamonti, Casucci et al., 2000; Mystakidou, Tsilika, Kalaidopoulou et al., 2002). Long-acting octreotide, given as a monthly intramuscular injection, may be an option for patients requiring long-term administration (Matulonis, Seiden, Roche et al., 2005). Octreotide is an expensive medication. More research is needed to determine if the costs of this medication make it appropriate for first-line therapy or if other, less-expensive medications to control the symptoms of obstruction should undergo a trial first.

There are times, however, when pharmacological measures fail, leading to intractable vomiting. When this occurs, nasogastric decompression and parenteral hydration are preferable to the suffering produced by unremitting emesis (Waller & Caroline, 2000).

Enteral stents may be used as a less-invasive alternative to surgery for the palliation of unresectable bowel obstructions or to manage symptoms until surgery is scheduled (Baron, Rey, & Spinelli, 2002; Del Piano, Ballare, Montino et al., 2005; Vazquez-Iglesias, Gonzalez-Conde, Vasques-Millan et al., 2005).

Nausea and vomiting interfere with the oral administration of medications to treat the symptoms of obstruction as well as all other medications. Review all medications, discontinue medications that are no longer needed at this time, and select an appropriate alternative route of administration for those medications that are needed for symptom control. Alternative routes may include the sublingual, rectal, transdermal, subcutaneous, or intravenous routes.

PATIENT AND FAMILY EDUCATION

The symptoms of bowel obstruction are extremely uncomfortable and frightening and negatively impact quality of living. Patients and family members need to be kept informed about the potential cause of the symptoms, the interventions that will be used to control symptoms until a definitive diagnosis is made, and the treatment options (including benefits and burdens of each). Instruct the patient and family on the dose and administration of all new medications as well as changes in routes of administration of routine medications required because of nausea and vomiting. Prepare patients and family members for any surgical interventions or invasive procedures. Instruct the patient and family regarding signs and symptoms of recurring or worsening obstruction and encourage them to report these symptoms immediately. The fear of a recurring obstruction may increase anxiety in both the patient and family. Provide emotional support and make referrals to other members of the interdisciplinary team, including the social worker, chaplain, or counselor.

EVALUATION AND PLAN FOR FOLLOW-UP

“The goal of medical management is to decrease pain, nausea, and secretions into the bowel so to eliminate the need for a nasogastric (NG) tube and IV hydration” (von Gunten & Muir, 2002, p. 740). If the pharmacological management of the obstruction is effective, some patients may tolerate being tapered from the analgesics, antiemetics, antisecretory medications, and corticosteroids; other patients will need to be maintained on these medications for the remainder of their lives.

Recurrence of bowel obstruction and multiple bowel obstructions are possible in patients with advanced cancer who have had a previous obstruction. Monitor for any new onset of symptoms and institute symptomatic therapies immediately.

Mr. J. is 72 years old and has metastatic colon cancer. He had a colectomy with anastomosis 3 years ago followed by chemotherapy. Liver metastasis was diagnosed 6 months ago. He is at home with an interdisciplinary hospice team providing care to him and his wife. His current medications include controlled-release oxycodone 20 mg by mouth every 12 hours for abdominal pain related to his enlarged liver, 5 mg of immediate-release oxycodone by mouth as needed for breakthrough pain, and a combination stimulant/softener laxative.

Mr. J. reports that he is having intermittent sharp pains in his abdomen. Two days ago he had a very small bowel movement of soft stool. He has not vomited but says he feels nauseated and has no appetite. He has had only sips of fluids in the past 24 hours. Upon physical examination, the clinician notes slight abdominal distention, high-pitched bowel sounds, no palpable abdominal masses, and a small amount of soft stool in the rectum. A partial bowel obstruction is suspected. Mr. J. states that he does not want to go back to the hospital unless it is absolutely necessary.

After consultation with the patient, family, and surgeon, a decision is made to treat the potential obstruction pharmacologically at home and to evaluate the effectiveness. Because Mr. J. is still able to swallow and has not had any vomiting, he is started on a regimen of oral metoclopramide 10 mg every 8 hours to treat nausea and increase bowel motility, dexamethasone 8 mg every 8 hours to decrease inflammation in the bowel, and hyoscyamine 0.25 mg every 4 hours for 24 hours and then every 4 hours as needed to treat the colicky pain. His oxycodone regimen is continued and an additional stool softener is added to his bowel protocol.

After 24 hours on the new regimen, Mr. J. reports a decrease in the sharp abdominal pains, although he feels “twinges” on occasion, and no nausea. After 72 hours, he is eating small amounts of soft foods and is able to take in fluids throughout the day. He reports a moderate-size soft bowel movement. The dexamethasone is tapered to 4 mg every 8 hours and he does not require any hyoscyamine after 7 days.

Mr. J. eventually becomes unable to swallow medications, although he is still able to sip some fluids. Although weak, he does not appear to be imminently dying and there is concern about recurrent bowel obstruction and management of his pain. Rectal administration versus subcutaneous infusion of an opioid, metoclopramide, and dexamethasone is discussed as options with Mr. and Mrs. J. Mr. J. does not want his wife to have to give him suppositories around the clock. Hypodermoclysis at a rate of 100 ml/hr of {2/3} normal saline is initiated to maintain hydration and a subcutaneous infusion of metoclopramide 1.5 mg/hr, dexamethasone 0.5 mg/hr, and hydromorphone 0.1 mg/hr (approximately 75% of the equianalgesic dose of oxycodone) is started. Nursing visits are scheduled daily for the first 3 days of therapy to ensure that Mr. J. is tolerating the infusion and that Mrs. J. is comfortable with instructions regarding both the hypodermoclysis and the ambulatory infusion pump with the medications. When Mr. J. becomes too weak to use a urinal, a urinary catheter is placed to ensure continuous drainage. Over the next 3 weeks, the hydromorphone dosage is titrated up to 1 mg/hr due to reports of pain. He remains lethargic but able to communicate until 24 hours before he dies peacefully at home.

REFERENCES

Baron, T.H.; Rey, J.; Spinelli, P., Expandable metal stent placement for malignant colorectal obstruction, Endoscopy 34 (10) ( 2002) 823–830.

Cowan, J.D.; Palmer, T.W., Practical guide to palliative sedation, Curr Oncol Reports 4 (3) ( 2002) 242–249.

Dang, C.; Aguilera, P.; Dang, A.; et al., Acute abdominal pain: Four classifications can guide assessment and management, Geriatrics 57 (3) ( 2002) 30–42.

Davis, M.P.; Nouneh, C., Modern management of cancer-related intestinal obstruction, Curr Oncol Reports 2 (4) ( 2000) 343–350.

Del Piano, M.; Ballare, M.; Montino, F.; et al., Endoscopy or surgery for malignant GI outlet obstruction?Gastrointestin Endosc 61 (3) ( 2005) 421–426.

Fazio, V.W.; Cohen, Z.; Fleshman, J.W.; et al., Reduction in adhesive small-bowel obstruction by Seprafilm adhesion barrier after intestinal resection, Diseases of the Colon and Rectum 49 (1) ( 2006) 1–11.

Hasler, W., Motility of the small intestine and colon, In: (Editors: Yamada, T.; Alpers, D.H.) The textbook of gastroenterology4th ed. ( 2003)Lippincott, William, & Wilkins, Philadelphia, pp. 220–239.

Hirst, B.; Regnard, C., Management of intestinal obstruction in malignant disease, Clinical Med 3 (4) ( 2003) 311–314.

Jenkins, J.T.; Taylor, A.J.; Behrns, K.E., Secondary causes of intestinal obstruction; rigorous preoperative evaluation is required, Am Surgeon 66 (7) ( 2000) 662–666.

Low, R.N.; Chen, S.C.; Barone, R., Distinguishing benign from malignant bowel obstruction in patients with malignancy: Findings at MR imaging, Radiology 228 (1) ( 2003) 157–165.

Matulonis, U.A.; Seiden, M.V.; Roche, M.; et al., Long-acting octreotide for the treatment and symptomatic relief of bowel obstruction in advanced ovarian cancer, J Pain Symptom Manage 30 (6) ( 2005) 563–569.

Mercadante, S.; Ferrera, P.; Villari, P.; et al., Aggressive pharmacological treatment for reversing malignant bowel obstruction, J Pain Symptom Manage 28 (4) ( 2004) 412–416.

Mercadante, S.; Ripamonti, C.; Casucci, A.; et al., Comparison of octreotide and hyoscine butylbromide in controlling gastrointestinal symptoms due to malignant inoperable bowel obstruction, Support Care Cancer 8 (3) ( 2000) 188–191.

Miller, G.; Boman, J.; Shrier, I.; et al., Small-bowel obstruction secondary to malignant disease: An 11-year audit, Can J Surg 43 (5) ( 2000) 353–358.

Mystakidou, K.; Tsilika, E.; Kalaidopoulou, O.; et al., Comparison of octreotide administration vs conservative treatment in the management of inoperable bowel obstruction in patients with far advanced cancer: A randomized, double-blind, controlled clinical trial, Anticancer Res 22 (2B) ( 2002) 1187–1192.

Pappagallo, M., Incidence, prevalence, and management of opioid bowel dysfunction, Am J Surg 182 (5A Suppl) ( 2001) 11S–18S.

Ripamonti, C.; Mercadante, S., Pathophysiology and management of malignant bowel obstruction, In: (Editors: Doyle, D.; Hanks, G.; Cherny, N.; et al.) Oxford textbook of palliative medicine3rd ed. ( 2004)Oxford University Press, New York, pp. 496–506.

Ryan, M.D.; Wattchow, D.; Walker, M.; et al., Adhesional small bowel obstruction after colorectal surgery, Aus N Z J Surg 74 (1) ( 2004) 1010–1012.

Smith, D.S.; Williams, C.S.; Ferris, C.D., Diagnosis and treatment of chronic gastroparesis and chronic intestinal pseudo-obstruction, Gastroenterol Clin North Am 32 (2) ( 2003) 619–658.

Summers, R.W., Approach to the patient with ileus and obstruction, In: (Editors: Yamada, T.; Alpers, D.H.; Laine, L.; et al.) The textbook of gastroenterology4th ed. ( 2003)Lippincott Williams, & Wilkins, Philadelphia, pp. 829–843.

Sutton, D.H.; Harrell, S.P.; Wo, J.M., Diagnosis and management of adult patients with chronic intestinal pseudoobstruction, Nutr Clin Pract 21 (1) ( 2006) 16–22.

Taourel, P.; Kessler, N.; Lesnik, A.; et al., Helical CT of large bowel obstruction, Abdom Imag 28 (2) ( 2003) 267–275.

Twycross, R.G.; Wilcock, A., Alimentary symptoms: Obstruction, In: (Editors: Twycross, R.; Wilcock, A.) Symptom management in advanced cancer3rd ed. ( 2001)Radcliffe Medical Press, Oxford, pp. 111–115.

Vazquez-Iglesias, J.L.; Gonzalez-Conde, B.; Vazquez-Millan, M.A.; et al., Self-expandable stents in malignant colonic obstruction: Insertion assisted with a sphincterotome in technically difficult cases, Gastrointestin Endosc 62 (3) ( 2005) 436–437.

von Gunten, C.; Muir, J.C., Fast facts and concepts #45: Medical management of bowel obstruction, J Palliat Med 5 (5) ( 2002) 739–740.

Waller, A.; Caroline, N.L., Handbook of palliative care in cancer. 2nd ed. ( 2000)Butterworth-Heinemann, Boston.