CASE 18 Unsuccessful Coronary Intervention

Cardiac catheterization

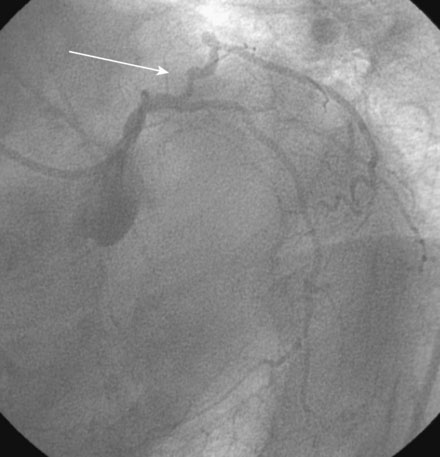

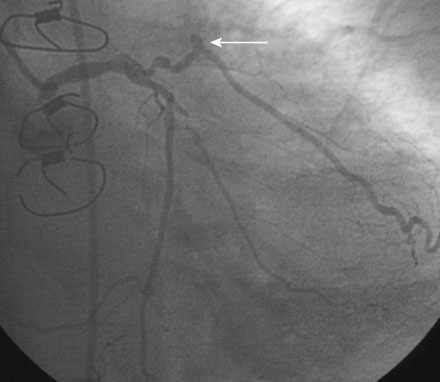

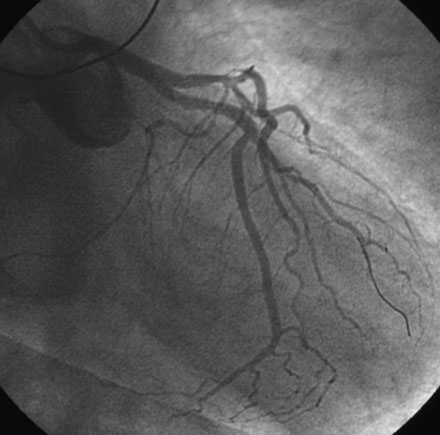

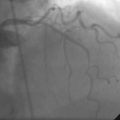

The diagnostic angiograms demonstrated occlusion of the native right coronary and left anterior descending coronary artery with occlusion of both saphenous vein grafts. A widely patent left internal mammary graft supplied a large left anterior descending artery. Severe disease of the proximal segment of a large first obtuse marginal artery as well as severe disease of a smaller-caliber second obtuse marginal artery likely accounted for her clinical presentation (Figures 18-1, 18-2 and Video 18-1). Based on these angiograms, stress test results, and her symptoms of progressive angina, her physician decided to revascularize the first obtuse marginal artery percutaneously.

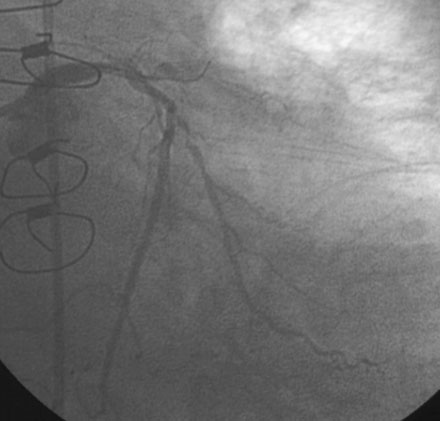

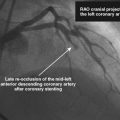

After selective engagement of the left coronary ostium with a 6 French JCL 4.5 guide catheter, and following administration of an intravenous bolus followed by an infusion of bivalirudin, a floppy-tipped 0.014 inch guidewire was advanced to the lesion. The wire tip successfully crossed the two lesions but was unable to advance around the sharply angulated segment, due to tethering of the vessel from the previously placed saphenous vein graft (Figure 18-3). Despite prolonged attempts and the incorporation of various curves applied to the wire tip, followed by the use of a hydrophilic-tipped guidewire (Boston Scientific, PT2), the operator failed to successfully gain access to the distal part of the artery. Additional manipulations ultimately closed the artery (Figure 18-3 and Videos 18-2, 18-3) and the patient experienced chest discomfort but remained hemodynamically stable. Fortunately, removal of the guidewire and administration of intracoronary nitroglycerin led to restoration of vessel patency (Video 18-4); there also appeared to be small dissection flaps within the diseased segment caused by the attempts. The operator abandoned further attempts at percutaneous revascularization and the patient left the cardiac catheterization laboratory with no electrocardiographic changes and noting only minimal chest discomfort.

Discussion

In the current era, the success rate of percutaneous coronary interventions exceeds 90%, a testimony to the remarkable advances in pharmacology, equipment, and techniques over the past several decades. Several terms are used to define success: 1) angiographic success, 2) procedural success, and 3) clinical success. Angiographic success indicates the presence of less than 20% residual stenosis at the treated lesion. Procedural success is defined as the presence of angiographic success along with the absence of a major complication (death, myocardial infarction, or need for emergency bypass surgery), and clinical success is present when there is procedural success plus improvement in symptoms. Current rates of angiographic and procedural success rates are very high, approaching 95% and 92% respectively.1

In this case, the attempt to cross with a guidewire led to abrupt vessel closure and a periprocedural myocardial infarction; fortunately the artery reopened spontaneously, limiting the extent of myocardial damage. Guidewire-induced trauma is one cause of abrupt closure after a coronary intervention; additional mechanisms include elastic recoil, dissection, spasm, and thrombus. In the pre-stent era, abrupt vessel closure complicated 2% to 8% of coronary balloon angioplasties. The morbidity of these events was substantial; nearly one third of these required emergency bypass surgery, and there was a high rate of Q-wave myocardial infarction and death.2 The advances in pharmacology preventing procedural thrombus and the routine use of coronary stents targeting recoil and dissection reduced the incidence of sustained abrupt vessel closure to less than 1% and the need for emergency bypass surgery to the current, nearly negligible levels.

1 Anderson H.V., Shaw R.E., Brindis R.G., Hewitt K., Krone R.J., Block P.C., McKay C.R., Weintraub W.S. A contemporary overview of percutaneous coronary interventions. The American College of Cardiology-National Cardiovascular Data Registry (ACC-NCDR). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;39:1096-1103.

2 Klein L.W. Coronary complications of percutaneous coronary intervention: A practical approach to the management of abrupt vessel closure. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2005;64:395-401.