CHAPTER 18

Scapular Winging

Definition

Scapular winging refers to prominence of the vertebral (medial) border of the scapula [1]. The inferomedial border can also be rotated or displaced away from the chest wall. This well-defined medical sign was first described by Velpeau [2] in 1837. It is associated with a wide array of medical conditions or injuries that typically result in dysfunction of the scapular stabilizers and rotators and, ultimately, glenohumeral and scapulothoracic biomechanics.

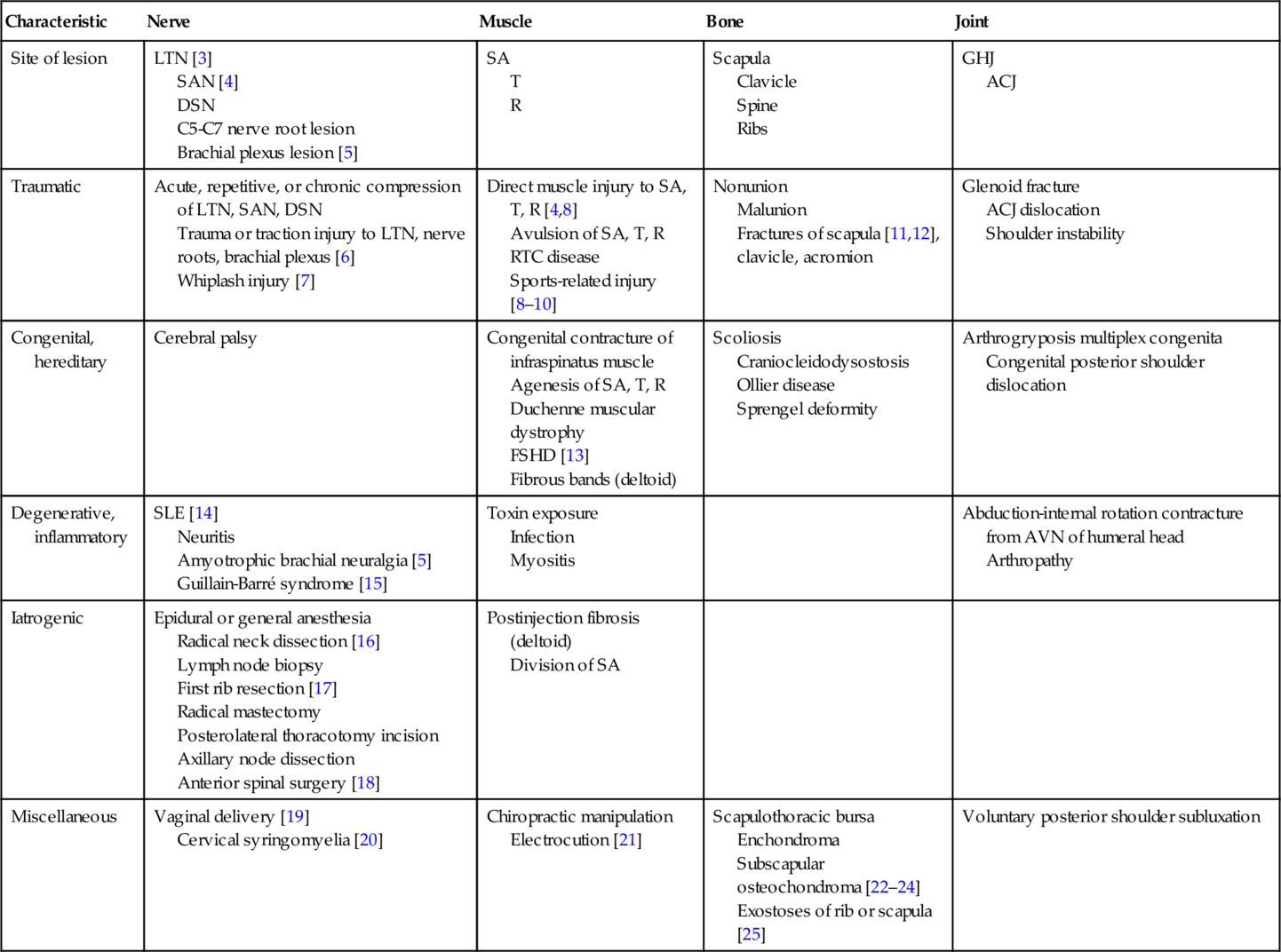

Fiddian and King [1] classified scapular winging as either static or dynamic after examination of 25 patients with 23 different causes of scapular winging. Static winging is attributable to a fixed deformity in the shoulder girdle, spine, or ribs; it is characteristically present with the patient’s arms at the sides. Dynamic winging is ascribed to a neuromuscular disorder; it is produced by active or resisted movement and is usually absent at rest. Scapular winging has also been classified anatomically according to whether the etiology of the lesion is related to nerve, muscle, bone, or joint disease (Table 18.1).

Table 18.1

Etiology of Scapular Winging

| Characteristic | Nerve | Muscle | Bone | Joint |

| Site of lesion | LTN [3] SAN [4] DSN C5-C7 nerve root lesion Brachial plexus lesion [5] |

SA T R |

Scapula Clavicle Spine Ribs |

GHJ ACJ |

| Traumatic | Acute, repetitive, or chronic compression of LTN, SAN, DSN Trauma or traction injury to LTN, nerve roots, brachial plexus [6] Whiplash injury [7] |

Direct muscle injury to SA, T, R [4,8] Avulsion of SA, T, R RTC disease Sports-related injury [8–10] |

Nonunion Malunion Fractures of scapula [11,12], clavicle, acromion |

Glenoid fracture ACJ dislocation Shoulder instability |

| Congenital, hereditary | Cerebral palsy | Congenital contracture of infraspinatus muscle Agenesis of SA, T, R Duchenne muscular dystrophy FSHD [13] Fibrous bands (deltoid) |

Scoliosis Craniocleidodysostosis Ollier disease Sprengel deformity |

Arthrogryposis multiplex congenita Congenital posterior shoulder dislocation |

| Degenerative, inflammatory | SLE [14] Neuritis Amyotrophic brachial neuralgia [5] Guillain-Barré syndrome [15] |

Toxin exposure Infection Myositis |

Abduction-internal rotation contracture from AVN of humeral head Arthropathy |

|

| Iatrogenic | Epidural or general anesthesia Radical neck dissection [16] Lymph node biopsy First rib resection [17] Radical mastectomy Posterolateral thoracotomy incision Axillary node dissection Anterior spinal surgery [18] |

Postinjection fibrosis (deltoid) Division of SA |

||

| Miscellaneous | Vaginal delivery [19] Cervical syringomyelia [20] |

Chiropractic manipulation Electrocution [21] |

Scapulothoracic bursa Enchondroma Subscapular osteochondroma [22–24] Exostoses of rib or scapula [25] |

Voluntary posterior shoulder subluxation |

From Fiddian NJ, King RJ. The winged scapula. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1984;185:228-236.

ACJ, acromioclavicular joint; AVN, avascular necrosis; DSN, dorsal scapular nerve; FSHD, facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy; GHJ, glenohumeral joint; LTN, long thoracic nerve; R, rhomboid muscles; RTC, rotator cuff muscles; SA, serratus anterior muscle; SAN, spinal accessory nerve; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus; T, trapezius muscle.

The scapula is a triangular bone that is completely surrounded by muscles and attaches to the clavicle by the coracoclavicular ligaments and acromioclavicular joint capsule. Motion of the scapula along the chest wall occurs through the action of the muscle groups that originate or insert on the scapula and proximal humerus. These muscles include the rhomboids (major and minor), trapezius, serratus anterior, levator scapulae, and pectoralis minor. The rotator cuff and deltoid muscles are involved with glenohumeral motion. Innervation of these muscle groups includes all the roots of the brachial plexus and several peripheral nerves. Scapular winging may be caused by brachial plexus injuries but most often is related to a peripheral nerve injury (see Table 18.1).

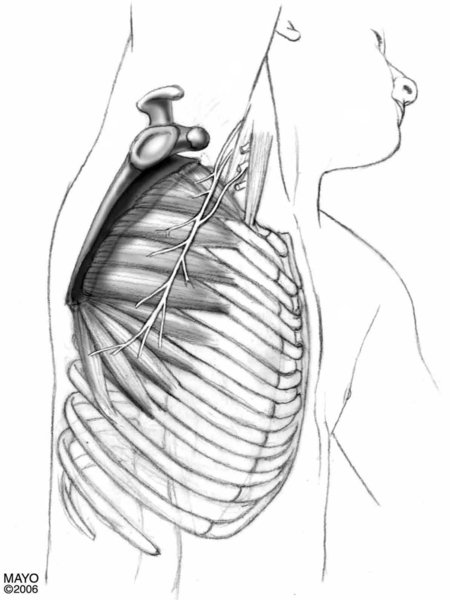

Injury to the long thoracic and spinal accessory nerves with weakness of the serratus anterior and trapezius muscles, respectively, is most commonly associated with scapular winging. The serratus anterior muscle originates on the outer surface and superior border of the upper eight or nine ribs and inserts on the costal surface of the medial border of the scapula. It abducts the scapula and rotates it so the glenoid cavity faces cranially and holds the medial border of the scapula against the thorax.

The serratus anterior muscle is innervated by the pure motor long thoracic nerve, which arises from the ventral rami of the fifth, sixth, and seventh cervical roots. The nerve passes through the scalenus medius muscle, beneath the brachial plexus and the clavicle, and over the first rib. It then runs superficially along the lateral aspect of the chest wall to supply all the digitations of the serratus anterior muscles [26]. Because of its long and superficial course, the long thoracic nerve is susceptible to both traumatic and nontraumatic injuries (Fig. 18.1).

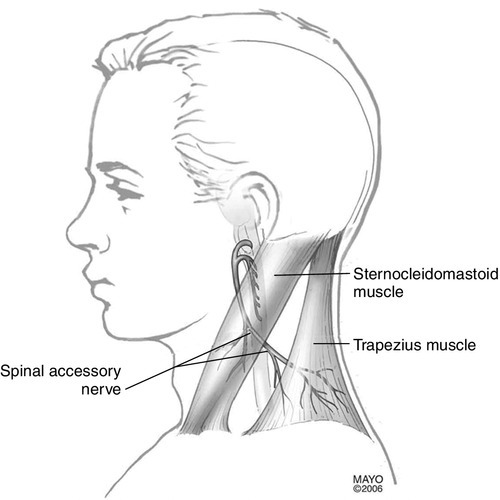

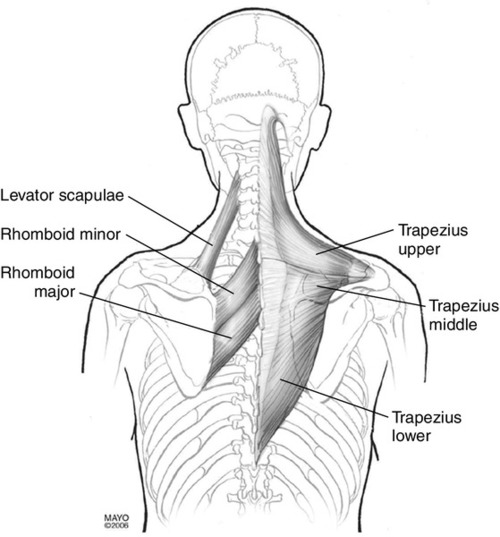

The trapezius muscle consists of upper, middle, and lower fibers. The upper fibers originate from the external occipital protuberance, superior nuchal line, nuchal ligament, and spinous process of the seventh cervical vertebra and insert on the lateral clavicle and acromion. The middle fibers arise from the spinous process of the first through fifth thoracic vertebrae and insert on the superior lip of the scapular spine. The lower fibers originate from the spinous process of the sixth through twelfth thoracic vertebrae and insert on the apex of the scapular spine. They are innervated by the pure motor spinal accessory nerve (cranial nerve XI) and afferent fibers from the second through fourth cervical spinal nerves. The root fibers unite to form a common trunk that ascends to enter the intracranial cavity through the foramen magnum. It exits with the vagus nerve through the jugular foramen, pierces the sternocleidomastoid muscle, and descends obliquely across the floor of the posterior triangle of the neck to the trapezius muscle [26]. In the posterior triangle, the nerve lies superficially, covered only by fascia and skin, and is susceptible to injury. Cadaver studies have shown considerable variations in the course and distribution of the spinal accessory nerve in the posterior triangle and in the nerve’s relationship to the borders of the sternocleidomastoid and trapezius muscles [27]. The trapezius muscle adducts the scapula (middle fibers), rotates the glenoid cavity upward (upper and lower fibers), and elevates and depresses the scapula. Overall, the trapezius muscles maintain efficient shoulder function by both supporting the shoulder and stabilizing the scapulae (Fig. 18.2).

A rare cause of scapular winging is dorsal scapular nerve palsy. The dorsal scapular nerve is a pure motor nerve from the fifth cervical spinal nerve that supplies the rhomboid and levator scapulae muscles. It arises above the upper trunk of the brachial plexus and passes through the middle scalene muscle on its way to the levator scapulae and rhomboids. The rhomboids (major and minor) adduct and elevate the scapula and rotate it so the glenoid cavity faces caudally [26].

The levator scapulae muscles originate on the transverse process of the first four cervical vertebrae and insert on the medial borders of the scapulae between the superior angle and the root of the spine. They elevate the scapulae and assist in rotation of the glenoid cavity caudally. They are innervated by the dorsal scapular nerve (emanating from the fifth cervical spinal nerve) and the cervical plexus (emanating from the third and fourth cervical spinal nerves) (Fig. 18.3).

Symptoms

A patient’s presenting symptoms depend on the type and chronicity of the injury. Most patients, however, complain of upper back or shoulder pain, muscle fatigue, and weakness with use of the shoulder. The diagnosis of scapular winging is made clinically. A pain profile should be obtained, including onset and duration of pain, location, severity, and quality as well as exacerbating and relieving factors, not only to provide baseline information but also to help develop a differential diagnosis. The patient should also be questioned about hand dominance because the dominant shoulder is usually more muscular but sits lower than the nondominant shoulder. Knowledge of the patient’s age, occupation and hobbies, and current and previous level of functioning may also contribute to the diagnosis and treatment plan. The mechanism of injury in patients with traumatic palsy is important, as are associated findings including muscle spasm, paresthesia, and muscle wasting or weakness [28,29]. The scapular winging of long thoracic neuropathy and serratus anterior muscle weakness must be distinguished from that of a spinal accessory neuropathy and trapezius muscle weakness as well as dorsal scapular neuropathy and rhomboid weakness. Serratus anterior muscle dysfunction is the most common cause of scapular winging. Typically, patients complain of a dull aching pain in the shoulder and periscapular region. The periscapular pain may be related to spasm from unopposed contraction of the other scapular stabilizers in the presence of serratus anterior muscle weakness. There may be “clicking” or “popping” noise emanating from the periscapular area when the patient moves, which is made worse with stressful upper extremity activities [28]. Because the serratus anterior muscle rotates the scapula forward as the arm is abducted or forward flexed above the shoulder level, these movements are affected. Shoulder fatigue and weakness are related to loss of scapular rotation and stabilization.

A cosmetic deformity may occur in the upper back as a result of the winged scapula. It may be apparent at rest but usually is more obvious on raising of the arm. Patients may find it difficult to sit for prolonged periods with the back resting against a hard surface, such as driving for long periods.

With trapezius muscle weakness, the affected shoulder is depressed, and the inferior scapular border rotates laterally, which makes prolonged use of the arm painful and tiresome. Patients often complain of a dull ache around the shoulder girdle and difficulty with overhead activities and heavy lifting, especially with shoulder abduction greater than 90 degrees [29].

Physical Examination

The patient should be suitably undressed so that the examiner can observe, both front and back, the normal bone and soft tissue contours of both shoulders and scapulae for symmetry and their relationship to the thorax. The patient’s overall posture is assessed, as are the presence of muscle spasm and trapezius or rhomboid muscle atrophy. Scapulothoracic motion is examined with both passive and active range of motion activities of the shoulder. The different patterns of scapulothoracic movement can assist in the differential diagnosis of scapular winging and are illustrated in Figures 18.4 to 18.6 [30].

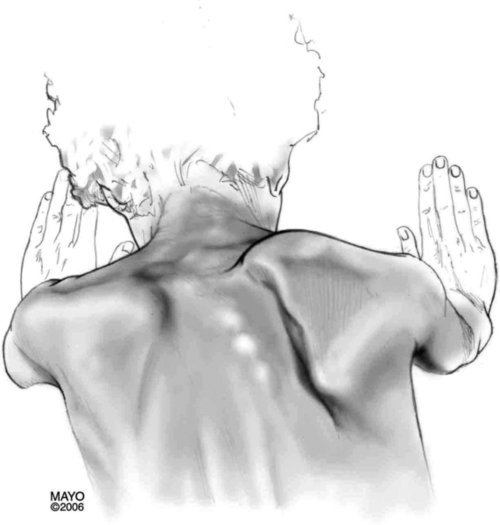

With long thoracic neuropathy and serratus anterior muscle weakness, the cardinal sign is winging of the scapula, in which the vertebral border of the scapula moves away from the posterior chest wall and the inferior angle is rotated toward midline. This scapular winging may be visible with the patient standing normally, but if the weakness is mild, it may be visible only when the patient extends the arm and pushes against a wall in a pushup position (Fig. 18.4) [3,28,31].

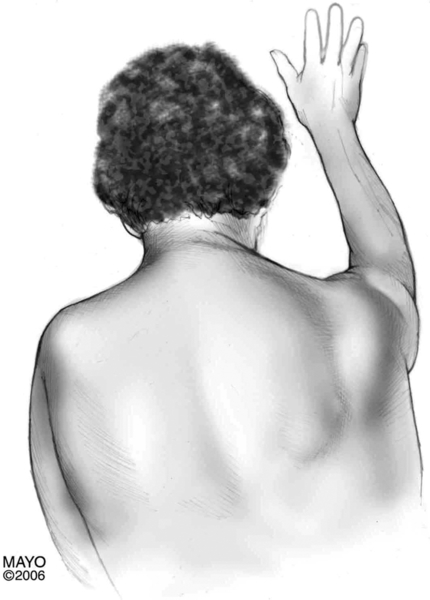

Spinal accessory neuropathy and trapezius muscle weakness are usually accompanied by an asymmetric neckline with noticeable shoulder droop when the patient’s arms are unsupported at the sides. On the affected side, deepening of the supraclavicular fossa is evident and shoulder shrug is difficult. With shoulder elevation, the scapula is displaced laterally, rotating downward and outward. There is usually difficulty with shoulder abduction above 90 degrees, more so than with forward flexion. Weakness with attempted shoulder elevation against resistance is characteristic. Normal muscle testing can elicit weakness in the trapezius muscle (Fig. 18.5) [29,32].

With weakness of the rhomboids, winging of the scapula is usually minimal. There is lateral displacement of the inferior angle of the scapula that is best accentuated when the patient pushes the elbow backward against resistance or slowly lowers the arms from a forward elevated position. Atrophy of the rhomboids may be present. The scapula is displaced downward and laterally (Fig. 18.6) [32].

A complete neurologic and musculoskeletal examination, with manual muscle strength testing and sensory and reflex testing, should be completed to rule out underlying neuromuscular disease processes. In addition, thorough examination of the neck and shoulder with provocative maneuvers should be completed to rule out additional musculoskeletal sources of scapular winging.

Functional Limitations

Functional limitations depend not only on the cause of the scapular winging but also on the severity of weakness and pain. Difficulty with activities of daily living may be evident as a result of pain, weakness, and altered scapulothoracic and glenohumeral motion. Especially affected are activities that require arm elevation above the level of the shoulder (e.g., brushing hair or teeth or shaving). Recreational and vocational activities such as golf, tennis, and volleyball that entail working or reaching overhead may be affected. Chronic shoulder pain and dysfunction can lead to depression and anxiety, irritability, concentration difficulties, lack of sleep, and chronic fatigue. Overuse of the shoulder and scapular stabilizer muscles can lead to myofascial pain syndromes.

Diagnostic Studies

Plain radiography of the shoulder, cervical spine, chest, and scapulae is recommended as part of the initial evaluation for scapular winging, especially if the cause is not obvious. Plain radiography can help rule out other causes of scapular winging, such as subscapular osteochondroma, avulsion fracture of the scapula, or other primary shoulder and cervical spine disease. With radiographs of the scapula, oblique views are recommended because osteochondroma may be hidden on anteroposterior views [33].

Computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging are usually not necessary unless the coexistence of other disease processes is suspected. The patient’s presentation and examination findings are pivotal in deciding whether advanced imaging is necessary.

Electrodiagnostic studies, namely, electromyography and nerve conduction studies, are valuable tools clinically to aid in the evaluation of scapular winging. They can assist in localizing injury and disease of peripheral nerves or muscles related to scapular function. These studies can help evaluate patients with abnormal scapulothoracic motion but in whom it cannot be clearly established clinically whether the weakness lies in a particular muscle or in the actions of other muscles acting on the scapula.

Serial electromyographic and nerve conduction studies have been used to follow recovery in patients with isolated long thoracic or spinal accessory nerve palsies and to help in decisions of whether to undertake nerve exploration or muscle transfer [28,29]. However, caution has been advised in the use of needle electromyographic findings to predict the prognosis and to guide the timing of surgical repair [34]. Long thoracic and spinal accessory neuropathies may be associated with a good prognosis, irrespective of needle electromyographic findings.

Treatment

In most patients, scapular winging is a result of neurapraxic injuries. Fortunately, these types of injuries usually resolve spontaneously within 6 to 9 months after traumatic injury and within 2 years after nontraumatic injuries. In one study [34], traumatic long thoracic and spinal accessory nerve injuries were associated with a poor prognosis compared with nontraumatic neuropathies. Once the diagnosis is made, conservative treatment should be initiated. Some clinicians have recommended a trial of conservative treatment for at least 12 to 24 months to allow adequate time for nerve recovery [28,29].

Initial

Pain control may be achieved early with use of an analgesic or an anti-inflammatory medication. Activity modification is recommended. The patient should avoid precipitating activities and strenuous use of the involved extremity. Physical modalities, such as ice massage, superficial moist heat, and ultrasound, can be applied to help with pain control. Ice massage may additionally help control swelling and relieve associated muscle spasm [32].

Immobilization should be a part of the initial management to prevent overstretching of the weakened muscle [35]. This can be accomplished with the use of a sling to rest the arm until the patient can recover brace-free shoulder flexion or have reduced pain. In one study, this could be anywhere from 1 to 7 months [36].

Long-term use of scapular winging shoulder braces to maintain the position of the scapula against the thorax is controversial. Various shoulder braces and orthotics have been used with mixed results. Some authors [8,31] recommend against use of shoulder braces because they are cumbersome, poorly tolerated, and ineffective. Others have advocated their use to protect against muscle overstretching and scapulothoracic overuse [32,35]. One author reported successful treatment of a brachial plexus injury and winged scapula with use of Kinesio tape and exercise to facilitate the rotator cuff groups and scapular stabilizers [36].

Rehabilitation

Specific treatment varies, depending on the etiology of the scapular winging. In general, range of motion exercises should be initiated early to prevent contractures or adhesive capsulitis, especially if the affected extremity is immobilized.

A stretching and strengthening exercise program can be undertaken after pain control is achieved [32]. Stretching the scapular stabilizers and shoulder capsules without overstretching the weakened muscle as well as cross-body adduction to stretch the rhomboids is important and should be supervised by a physical therapist. The scapular stabilizer, cervical muscles, and rotator cuff muscle should be strengthened, especially the affected muscle groups. This can be accomplished by passive scapular retraction, such as scapular squeeze. Isometric strengthening exercises can include scapular protraction and retraction, shoulder packing, and shoulder shrugs to strengthen the pectoralis, serratus anterior, rhomboids, upper trapezius, and levator scapulae. Advanced exercises can include specific rotator cuff strengthening as well as shoulder circles with a ball against a wall, stabilizing ball pushups, resistance band pull-aparts and pull-downs, and chest presses both standing and lying down. Neuromuscular electrical stimulation may be used to prevent muscle atrophy. Functional glenohumeral and scapulothoracic muscle patterns must be relearned. Progression to an independent structured home exercise program is recommended, but the patient should first be able to perform the exercises appropriately under supervision of a physical therapist.

Procedures

Localized injections are not routinely administered for isolated scapular winging. Injection therapy may be indicated for other coexisting shoulder disease to help with pain control.

Surgery

Conservative treatment has been recommended for a prolonged period (12 to 24 months) to allow adequate time for recovery before surgical options are considered. [28,29,37] Surgery should be considered for patients who do not recover in this time. In patients with penetrating trauma in which the nerve may have been injured, spontaneous recovery is less likely, and early nerve exploration with neurolysis, direct nerve repair, or nerve grafting may be indicated.

Surgery may also be indicated if scapular winging appears to have been caused by a surgically treatable lesion (e.g., a subscapular osteochondroma) and the patient is symptomatic or has a cosmetic disfigurement [22,38]. In general, surgical options are many but can be divided into two categories: static stabilization procedures and dynamic muscle transfers.

Static stabilization procedures involve scapulothoracic fusion and scapulothoracic arthrodesis in which the scapula is fused to the thorax. These procedures may be effective in cases of generalized weakness (e.g., facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy) when the patient has disabling pain and functional loss and no transferable muscles. [32,37,39,40] They can relieve shoulder fatigue and pain and allow functional abduction and flexion of the upper extremity [13,39]. Static stabilization procedures have fallen out of favor for scapular winging related to isolated muscle weakness because the results deteriorate over time with recurrence of winging. The usual incidence of complications associated with some of these procedures is high [32,39]. Dynamic muscle transfers have shown better results for correction of scapular winging and restoration of function. Several different muscles have been used in various muscle transfer techniques to provide dynamic control of the scapula and to improve scapulothoracic and glenohumeral motion. Transfer of the sternal head of the pectoralis major muscle to the inferior angle of the scapula with fascia lata autograft reinforcement is the preferred method of treatment for scapular winging related to long thoracic nerve injury. [32,37,41] The surgical procedure of choice for scapular winging related to chronic trapezius muscle dysfunction involves the lateral transfer of the insertions of the levator scapulae and the rhomboid major and minor muscles. This procedure enables the muscles to support the shoulder girdle and to stabilize the scapula [29,32,37].

Potential Disease Complications

Disease complications are usually related to scapulothoracic dysfunction as a result of scapular winging. This can contribute to glenohumeral instability and subsequent shoulder range of motion and functional deficits as well as chronic periscapular, upper back, and shoulder pain. Secondary impingement syndromes can result from the muscle dysfunction. Adhesive capsulitis can occur from loss of shoulder mobility and function. Cosmetic deformity is a common result of scapular winging, especially if there is a combined serratus anterior and trapezius muscle weakness.

Potential Treatment Complications

Pharmacotherapy can lead to treatment complications. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs have well-documented adverse effects that most commonly involve the gastrointestinal system. Analgesics may have adverse effects that predominantly involve the hepatorenal system. These complications can be minimized by having a working knowledge of the patient’s ongoing medical problems, current medications, and potential drug interactions.

Local injections may cause allergic reactions, infection at the injection site, and, rarely, sepsis. Tendon rupture is a potential complication if inadvertent injection into a tendon occurs.

Surgical complications are numerous and include a large, cosmetically unpleasant incision over the shoulder and upper back, postoperative musculoskeletal deformities (e.g., scoliosis), infection, pulmonary complications (e.g., pneumothorax and hemothorax), hardware failure, pseudarthrosis, recurrent winging, and persistent pain.