IDENTIFYING THE PROBLEM

In Australia, responsibility for the mental health system is shared between the Commonwealth, or Australian government, state and territory governments and the private sector. Through the Australian Health Care Agreements (AHCA), the Australian government contributes to the public health system overseen by state and territory jurisdictions. State funding provides for inpatient and community services in the public sector, providing approximately two-thirds of funding for mental health services overall. The Australian government contributes funds to the private non-inpatient services and private health insurance. Importantly, the introduction of the Medibank national health insurance scheme in 1974, superseded by Medicare in 1984, provided major reform in healthcare funding and facilitated change in mental health policy. In particular, inclusion of a schedule of rebates for specialist psychiatric consultation meant that no longer was virtually all specialist mental healthcare provided by the state system. The Australian government also funds services provided by primary care practitioners (general practitioners [GPs]) through the Medicare Benefits Schedule (MBS) and mental health pharmaceuticals through the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS) (see also Ch 4).

Both state and Australian government policy and funding decisions enabled the move from institutional-based to community-based care (‘deinstitutionalisation’) during the 1970s and 1980s. Underlying this move was the progressive ‘mainstreaming’ of mental health services, or the shift from stand-alone services to mental health being provided within the umbrella of general health services. These changes were accompanied by a significant reduction in the number of long-stay beds.

Initially adopted with enthusiasm, as time progressed problems and limitations of community-based care became evident. Symptoms that had been attributed to the institutional environment, such as withdrawal, self-neglect, self-harm and dangerous behaviour, were recognised as inherent to some illnesses and thus requiring ongoing attention irrespective of whether care was provided in an institution or in the community (Gruenberg 1969). In addition, it became clear that while social isolation, institutionalisation, neglect and ill treatment were seen in many asylums, they also occurred in hostels, halfway houses and other housing used by the mentally ill treated in the community (Finlay-Jones 1983). The needs of patients receiving care in the community for a range of non-health services, such as accommodation, vocational training, and recreational, social and disability supports, were often inadequate. Public concern about the care and treatment of the mentally ill, several well-publicised inquiries into psychiatric practices in specific hospitals in the late 1980s and early 1990s, and the Burdekin Report on the Human Rights of the Mentally Ill (Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission 1993) set the scene for major reform.

THE POLICY RESPONSES

In 1992, the Australian government, state and territory governments demonstrated increased commitment to mental healthcare and service delivery with the development of a National Mental Health (NMH) Strategy. This comprised three seminal documents: the National Statement of Rights and Responsibilities, the National Mental Health Policy and the first National Mental Health Plan (Australian Health Ministers’ Conference 1992). These set out to articulate the broad objectives and principles that would underpin service development and related legislative frameworks. All state and territory health ministers endorsed these documents.

The aims of the National Mental Health Policy are:

- to promote the mental health of the Australian community and, where possible, prevent the development of mental health problems and mental disorders

- to reduce the impact of mental disorders on individuals, families and the community

- to assure the rights of people with mental disorders.

- to reduce the impact of mental disorders on individuals, families and the community

Specifically, the key elements of the policy are:

- to enhance consumer rights and involvement in mental health services

- to mainstream mental health services into the general health sector

- to integrate inpatient and community mental health services

- to continue to downsize psychiatric hospitals and expand community mental health services

- to link mental health services with other social and disability services needed by people with mental illness

- to enhance the promotion of mental health and the prevention of mental disorders

- to increase support for carers and non-government organisations (NGOs).

- to mainstream mental health services into the general health sector

Additional objectives address workforce and service standards and include: to enhance the role of primary healthcare service providers, especially GPs, in providing mental healthcare; to improve the training and skills of mental health professionals and to address the maldistribution of the mental health workforce; to adopt nationally consistent mental health legislation and service standards; and to encourage mental health research and evaluation.

It should be noted that despite a push towards model mental health legislation that would be consistent across all jurisdictions, the complexity of mental health service provision, and its interaction with other state/territory-based legislative frameworks, has meant that all states and territories have their own mental health legislation. The policy underpinning state/territory-based legislation has been congruent with the national approach – emphasising care in the community where clinically appropriate, with attention to patient rights and external review. There remains variability in the timing of external review and the mechanisms involved, but the principles across the states and territories are consistent. The capacity to provide treatment in the community under involuntary treatment orders is also present in state-based legislation. Unlike New Zealand, and more recently Canada, Australia has not to date set up a national Mental Health Commission to oversee and monitor the implementation of the NMH Strategy.

The National Mental Health Plans

Since 1992, there have been three National Mental Health Plans. These have been agreed to by governments on both sides of the political arena, and have provided a national framework for the Australian government and the state and territory governments to implement mental health reform as defined in the National Mental Health Policy. Progress towards implementation of the policy has been documented through the annual National Mental Health Reports.

The first National Mental Health Plan (1992–1997) (Australian Health Ministers 1992) addressed a range of issues fundamental to the planning and delivery of mental health services in Australia. Specifically, it focused on the following areas: structural and system reform; standards; consumer rights; resource priorities; legislation; and data.

Structural reform involved activity in three key areas: an increase in community-based mental health services; ‘mainstreaming’ of mental health services into the general health sector; and a reduction in the size of stand-alone psychiatric hospitals. While all states and territories worked towards these goals, the degree of change and progress towards these goals was not uniform (Whiteford 1995).

State and territory funding for NGOs providing services for people with mental illness and psychiatric disability was increased. In addition, the NMH Strategy ensured that people with psychiatric disability had access to Australian government disability programs, including Australian government-funded employment services, which they had previously been denied (National Health Strategy 1993).

The Second National Mental Health Plan (1998–2003) (Australian Health Ministers 1998) was released after the results of the Australian National Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing became available (Australian Bureau of Statistics 1998). This large epidemiological study found that while almost one in five Australians met the criteria for one or more mental disorders during the 12 months before the survey, only 38% of people with a mental disorder used any type of conventional health service during this period. Informed by this study, the Second National Mental Health Plan (the Second Plan) acknowledged that some services had adopted an overly narrow interpretation of the original policy’s priority for people with serious mental illness, leaving many consumers without access to services. Thus, the plan included initiatives to address the clearly identified high level of unmet need.

As a consequence of the above, the Second Plan built on the first plan, but had a broader focus, with an emphasis on promotion of mental health and prevention and early intervention in mental disorders. This included the development of a Mental Health Promotion and Prevention Action Plan, which outlined a 5-year strategic framework and plan to meet the prevention and promotion priorities and outcomes in the Second Plan. The Second Plan also continued structural reform of mental health services with further expansion of community services and ‘mainstreaming’ of acute inpatient services into general hospitals.

In addition, the plan focused on developing partnerships in service reform and delivery. Informed by the work of the Joint Consultative Committee of the Royal Australian College of General Practitioners and the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists (1997) the plan also sought to achieve better integration between care provided by mental health professionals and primary care providers. Under the Second Plan, trials to integrate better public and private mental health sector services were undertaken with the aim of improving quality, appropriateness and efficiency of mental health service delivery (Eager et al. 2005).

The plan also promoted further developments in quality and effectiveness of care. Plans for the measurement and routine collection of consumer outcome measures in mental health services were introduced (Stedman et al. 1998), the National Standards for Mental Health Services (Department of Health and Family Services 1997) were incorporated into the Evaluation and Quality Improvement Program (EQuIP) Standards developed by the Australian Council on Healthcare Standards (1996), and the National Standards for the Mental Health Workforce (Department of Health and Ageing 2002) were released. The plan explicitly stated that the focus of services should be expanded to improve treatment and care for a broader range of people with high-level needs, but emphasised the need to continue service reforms for existing clients. The particular needs of Indigenous people, people from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds and those living in rural and remote areas were highlighted. In addition, a National Action Plan for Depression (Department of Health and Aged Care [DHAC] 2000) aimed to reduce both the prevalence and impact of depression. Target areas were defined to improve the level of mental health literacy about depression in the general community; to enhance the role of GPs through training, funding and support; and to ensure the workforce in Australian mental health services was used optimally.

The Second Plan was subjected to external review mid-way (Thornicroft & Betts 2001) by international experts. They concluded that the aims of the strategy and plans were admirable, and that Australia was well advanced in mental health policy and reform. They highlighted that progress had been uneven, and that many problems in access, and quality of service remained. The Second Plan, and mental health service delivery more generally, was also subjected to critical consideration by the Mental Health Council of Australia, a government-funded peak lobby group, which carried out extensive consultation through survey and community meetings. The conclusions of the council were far more critical, and were published in a report titled Out of Hospital; Out of Mind! (Groom et al. 2003).

The National Mental Health Plan (2003–2008) (Australian Health Ministers 2003) continued to build on the priorities of the previous two plans but expanded the focus of interest by adopting a population health framework. It included four priority themes: promoting mental health and preventing mental health problems and mental illness; increasing service responsiveness; strengthening quality; and fostering research, innovation and sustainability. The plan emphasised a whole-of-government approach and sought to improve Australia’s mental health through linkages with other areas of public policy, including housing, employment, justice, welfare and education. It continued to promote the rights of consumers and their families and carers, and emphasised the importance of a recovery orientation to service delivery. With its aim of achieving gains through a population health framework the plan considerably broadened the agenda, seeking to improve the treatment, care and quality of life for people with mental health problems as well as those with mental illness across the lifespan.

Changes under the National Mental Health (NMH) Strategy

State-funded mental health services

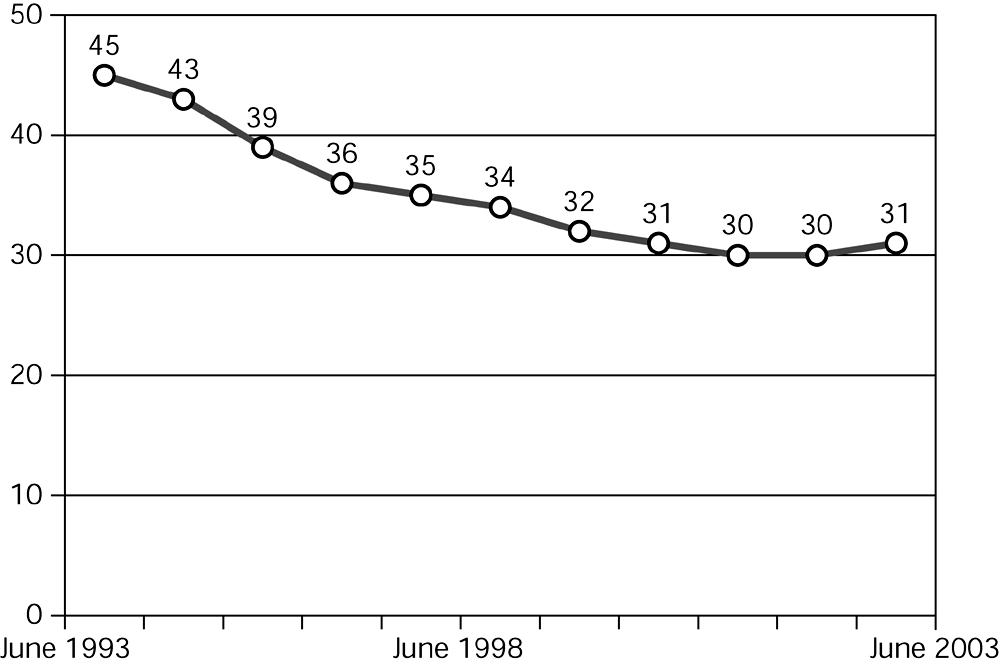

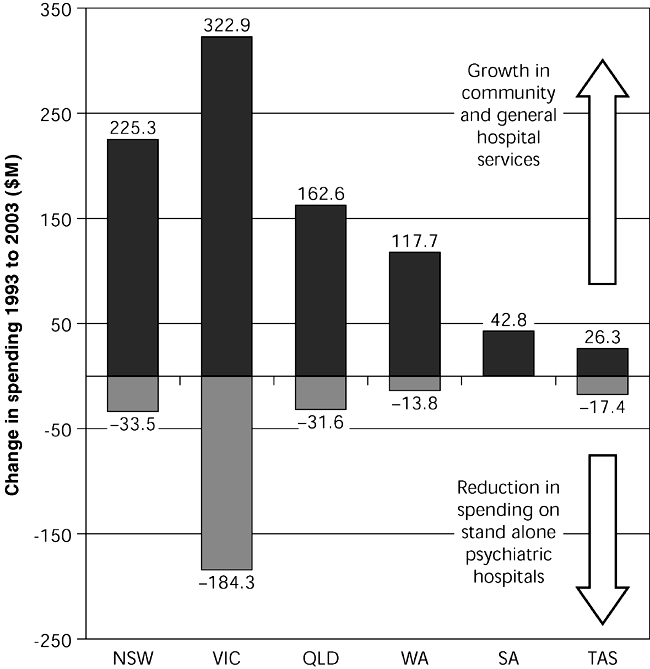

Under the NMH Strategy, there has been a significant reduction in the size and number of stand-alone psychiatric hospitals. They have been replaced by acute beds in general hospitals and a range of community-based services. In 1992–93, 71% of funds were allocated to hospitals and 29% to community-based services. By contrast, in 2002–03, 49% of funds were allocated to hospitals and 51% to community-based services (Department of Health and Ageing 2005; see Figs 18.1 & 18.2). The scale and pace of change has not been uniform across the states and territories. Victoria has implemented the most extensive structural changes. By contrast, in 2003 South Australia had not yet decreased its spending on stand-alone psychiatric hospitals relative to 1993 (Fig 18.2).

Figure 18.1 Total public sector inpatient beds per 100,000, June 1993 to June 2003 Source: Department of Health and Ageing 2005, Fig 22, copyright Commonwealth of Australia, reproduced by permission

Figure 18.2 Have savings from the reduction of state governments stand-alone psychiatric hospitals been transferred to alternative services? Source: Department of Health and Ageing 2005, Fig 17, copyright Commonwealth of Australia, reproduced by permission

Community-based services comprise three broad types of service: ambulatory care clinical services, specialised clinical residential services, and services provided by not-for-profit NGOs to provide support services for people with a psychiatric disability arising from a mental illness. In 1992–93, 23%, 4.4% and 2% of expenditure on mental health services was allocated to ambulatory, residential and NGO services respectively. In 2002–03 this had changed to 38.6%, 7.3% and 5.2%. (Department of Health and Ageing 2005). These figures disguise the significant variability across the states and territories. For example, in 2003 the percentage of total mental health service expenditure allocated to NGOs was 11.5% in Victoria, 11.4% in ACT, and least in South Australia (2.1%) and New South Wales (2.4%). Overall, although community treatment and support services have been strengthened, formal evaluation of progress has acknowledged that community treatment options are still inadequate (DHAC 2000).

Private sector and primary care services

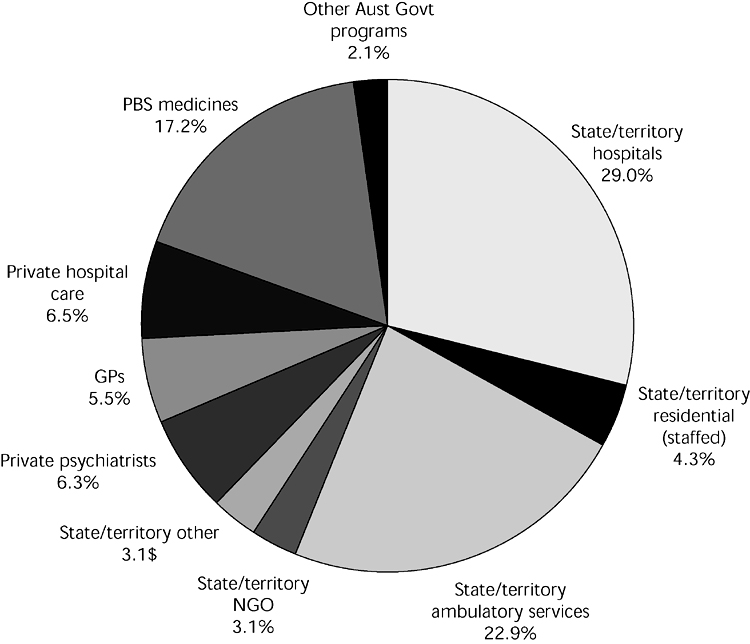

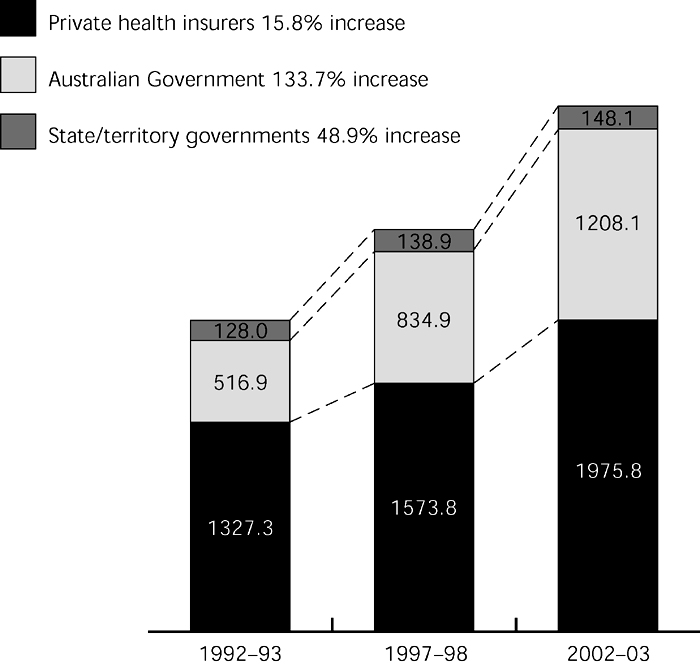

The importance of the private sector in the delivery of mental health services has been increasingly recognised. By 2002–03, the private sector provided 22% of total psychiatric beds and approximately 1.4% of Australians saw a private psychiatrist at least once a year (Department of Health and Ageing 2005; see Figs 18.3 & 18.4). However, there continues to be a significant maldistribution of private psychiatric services. Victoria and South Australia had the highest level of private psychiatrist services in 2002–03, with MBS benefits per capita 34% above the national average. By contrast, in the Northern Territory, Western Australia, Tasmania and the ACT, access to private consultant psychiatrist services is substantially lower than the larger states. Within individual states and territories, consultant psychiatrists are concentrated in capital cities and the majority of people attending for treatment come from metropolitan populations.

Figure 18.3 National spending on mental health, 2002–03 Source: Department of Health and Ageing 2005, Fig 4, copyright Commonwealth of Australia, reproduced by permission

Figure 18.4 National expenditure on mental health by source of funds, 1992–93 to 2002–03 ($millions) Source: Department of Health and Ageing 2005, Fig 5, copyright Commonwealth of Australia, reproduced by permission

The role of GPs as mental healthcare providers has been strengthened by key policy changes implemented through changes to the Medicare Benefits Schedule (MBS). The Better Outcomes in Mental Health Care (BOiMHC) Initiative (Hickie & Groom 2002), funded in the 2001–02 federal budget, was designed to advance primary mental healthcare in Australia. Incentive funding was provided for GPs to provide episodes of care, new MBS items were introduced to fund GPs who had participated in additional training in mental health to provide focused psychological strategies and pilot programs were funded to enable allied health specialists to provide non-pharmacological treatments on referral from GPs. Additional changes to the MBS in 2005 provided incentive payments for psychiatrists to provide consultation services to GPs and funded a service to enable GPs to consult about a psychiatric emergency.

Consumer and carer participation

Consumer and carer participation in mental health services has changed substantially under the NMH Strategy. In 1991, the Australian Health Ministers adopted a Mental Health Statement of Rights and Responsibilities. This, together with the National Mental Health Policy, has underpinned consumer empowerment and participation in mental health service delivery in Australia. All states and territories have consumer advisory groups to provide direct consumer and carer input to mental health policy and service delivery. In 1997, the Mental Health Council of Australia (MHCA) was established as the peak national NGO to represent and promote the interests of the Australian mental health sector. The council’s constituency includes consumers, carers, clinical service providers, NGOs and several special needs groups. Consumer and carer representatives comprise approximately one-quarter of the membership of the council (McGrath et al. 2002).

The National Standards for Mental Health Services (Department of Health and Family Services 1997) set expectations that all services will involve consumers and carers in the planning, implementation and evaluation of services. However, as for other changes under the NMH Strategy, development has not been uniform across all jurisdictions with 18% of mental health service organisations in 2003 remaining without a basic structural arrangement for consumer and carer participation. Consumer advocacy groups remain concerned that involvement is tokenistic and that investment in this area has fallen behind that directed to other areas in the plans.

Service quality and accountability

Key initiatives to improve service quality have been implemented. The National Practice Standards for the Mental Health Workforce (DHAC 2002) define the knowledge, attitudes and skills, which all mental health professionals should have. These are designed to complement discipline-specific skills. These are intended to be implemented during the 5 years of the Third National Mental Health Plan (the Third Plan). Complementary to this has been the introduction of individual consumer outcome measures into routine clinical practice in public mental services and private hospitals. All states and territories submit de-identified, patient-level outcome data to the Australian government for inclusion in national reporting. A suite of key performance indicators has been developed, including areas such as unplanned readmission rates, and community care pre- and post-admission (DHAC 2003).

Continuing problems despite the NMH Strategy

Although it is acknowledged that the NMH Strategy has led to structural reform, at the end of the Second Plan in 2003 significant problems in service delivery remained. Two influential reports (Groom et al. 2003, Mental Health Council of Australia 2005), together with the formal evaluation of the Second National Mental Health Plan (Thornicroft & Betts 2001), have supported the policy directions, but have been critical of the pace and extent of change that has been achieved. Formal evaluation has highlighted problems in the implementation of national policy, underpinned by lack of investment and commitment (Thornicroft & Betts 2001). Further, opinion leaders asserted that after a decade, reforms were losing momentum and core services were simply inadequate (Rosen et al. 2004).

In terms of commitment to mental health expenditure, growth mirrored overall health expenditure but was not sufficient to meet the level of unmet need for mental health services. There has been no proportional increase in the total health expenditure devoted to mental health, with total mental health spending in 2003 accounting for only 7% of government health spending (Department of Health and Ageing 2005). By 2003 Australia lagged behind similar Western countries in terms of commitment to and funding of mental health services (World Health Organization [WHO] 2001).

Despite policy direction and funding to develop service delivery arrangements to enhance coordination and integration of public and private mental health services, mental health services remained fragmented and disjointed. Parallel systems continued to operate: the private vs the public system; federal (Australian government) vs state/territory-based services and initiatives; and primary vs specialist care. Progress towards continuity of care was limited, and intersectoral collaboration has not been developed in a systematic or coordinated way. Although policy has been agreed nationally, it has been implemented at a different pace and to varying degrees across the states and territories. National benchmarks for service components have not been agreed upon. There is not yet a consensus model for service planning and implementation.

Concern has been expressed by service providers and by advocacy groups that in some areas change has been too rapid or has gone beyond an optimal level.

Such concerns have centred on areas such as limited access to inpatient services, insufficient rehabilitation opportunities, possible movement of people to the criminal justice system who should have been managed within mental health services, and workforce availability. For example, inpatient service reductions have been substantial with 24% fewer psychiatric beds available in 2003 than at the beginning of the NMH Strategy. The decrease in hospital beds has selectively targeted units providing medium to longer-term care rather than acute care units. Inpatient reductions have not been uniform across the jurisdictions and have only been partially counterbalanced by community residential services (Department of Health and Ageing 2005; see Fig 18.2). Access to care generally, and beds in particular, has repeatedly been highlighted as a problem as has short length of inpatient stay and frequent readmissions. The NMH Strategy did not stipulate an optimum level or mix of inpatient services.

High levels of unmet need are consistently reported, and access to services is limited (Groom et al. 2003, Mental Health Council of Australia 2005). A recent report commissioned by the Victorian government (Boston Consulting Group 2006) suggested that up to 44% of those with a significant mental illness were not receiving appropriate treatment and care. Continuing concern is raised that people with ‘high prevalence’ disorders, such as anxiety and mood disorders, those with personality disorders, or with a combination of physical and mental health problems who had previously been treated in public mental health services, have difficulty accessing care. Despite the broadened focus of the Second Plan, admission policy focusing on the ‘seriously mentally ill’ left many individuals who did not suffer from psychotic disorders, but who were considerably disabled by mental illness or disorder, outside the responsibility of public mental health services. While some are now treated in private inpatient settings, those without private health insurance have to a large extent ‘fallen between the cracks’. Primary care practitioners report difficulty in appropriately managing this group. The AMA has consistently flagged concern regarding access and continues to make mental health one of its priority areas for further investment and reform (Parliament of Australia 2006a).

Many groups with special needs continue to experience variable levels of service. These include people with drug and alcohol problems, individuals with intellectual disability, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, people from non-English speaking backgrounds, refugees, survivors of torture and trauma, people with organic impairment with severe behavioural problems and homeless persons (Thornicroft & Betts 2001). Often, these people require the involvement of both specialist mental health services and a range of other providers. Silos of policy, funding, expertise and culture within both federal and state governments combine to provide barriers to such care.

A further serious and yet to be adequately addressed problem is the maldistribution of services. Residents of outer metropolitan and rural areas remain seriously disadvantaged with respect to specialist mental health services. While one-third of residents live in rural areas, only 9% of psychiatrists are resident there (Australian Medical Workforce Advisory Committee [AMWAC] 1999). The Medical Specialist Outreach Assistance Program funded by the Australian government’s Rural Health Strategy has included psychiatry, but it has been implemented in different ways across the jurisdictions with variable impact on workforce shortages. Initiatives developed under the NMH Strategy, intended to ensure services for rural and remote and other poorly serviced population groups, have been limited in scope and implementation. Again, there is often a disjunction between state/territory-funded services that are provided on an area basis, and market-driven federal-funded services.

FUTURE DIRECTIONS FOR POLICY DEVELOPMENT

The Senate Committee on Mental Health

In 2005, in response to adverse publicity and advocacy by consumers, carers and mental health professionals, the Senate created a Select Committee on Mental Health (Parliament of Australia 2006b) to conduct a wide-ranging inquiry into the extent to which the NMH Strategy had achieved its aims and objectives, the adequacy of various modes of care for people with a mental illness, and opportunities for improving coordination of delivery of funding and services to ensure the provision of appropriate and comprehensive care to people with mental illness. Evidence presented to the committee highlighted several recurrent themes consistent with the problems highlighted above. During the course of the inquiry, there was considerable debate in the media regarding mental health issues, and continuing concern expressed by advocacy groups and service elements on perceived deficiencies in the treatment and care available to those suffering mental illness (Ellingsen 2005).

The National Action Plan on Mental Health 2006–2011

In February 2006, the Council of Australian Governments (COAG) identified mental health as an issue of national significance and in April 2006, the Prime Minister announced federal funding of $1.8 billion over 5 years to improve mental health services in Australia. The announced commitments responded to many of the Senate Committee’s 91 recommendations. In July 2006, COAG agreed to a National Action Plan on Mental Health (COAG 2006).

The National Action Plan on Mental Health (the National Action Plan) provides a strategic framework that emphasises the need for coordination and collaboration between government (federal, state and territory), private and non-government providers in order to deliver a more seamless and connected care system. The National Action Plan endeavours to plot meaningful outcomes, including the measured prevalence of mental illness, participation in the workforce, and measures of service effectiveness. Indicators will be measured and reported on over the life of the plan. The four identified outcomes and their progress measures are shown in Box 18.1.

BOX 18.1 DESIRED OUTCOMES OF THE NATIONAL ACTION PLAN ON MENTAL HEALTH 2006–2011, AND PROGRESS MEASURES

- Reducing the prevalence and severity of mental illness in Australia

- Reducing the prevalence of risk factors that contribute to the onset of mental illness and prevent longer term recovery

- — rates of use of illicit drugs that contribute to mental illness in young people

- — rates of substance abuse.

- Increasing the proportion of people with an emerging or established mental illness who are able to access the right healthcare and other relevant community services at the right time, with a particular focus on early intervention

- — percentage of people with mental illness who receive mental healthcare

- — mental health outcomes of people who receive treatment from state and territory services and the private hospital system

- — the rates of community follow up for people within the first 7 days of discharge from hospital

- — readmissions to hospital within 28 days of discharge.

- — mental health outcomes of people who receive treatment from state and territory services and the private hospital system

- Increasing the ability of people with a mental illness to participate in the community, employment, education and training, including through an increase in access to stable accommodation

- — participation rates by people with mental illness of working age in employment

- — participation rates by young people aged 16-30 with mental illness in education and employment

- — prevalence of mental illness among people who are remanded or newly sentenced to adult and juvenile correctional facilities

- — prevalence of mental illness among homeless populations.

- — participation rates by young people aged 16-30 with mental illness in education and employment

- Reducing the prevalence of risk factors that contribute to the onset of mental illness and prevent longer term recovery

The National Action Plan outlines where federal, state and territory governments will significantly expand and improve their mental health services and access to them. Individual implementation plans, prepared by each government, commit approximately $4 billion dollars over 5 years. The federal government will expand funding in key areas of responsibility including: services delivered by private psychiatrists in the community, GPs, psychologists, mental health nurses, and other allied health professionals; labour market programs associated with assisting people with mental illness to find and stay in employment; and tertiary education with funding for training and scholarships. The states and territories have committed to enhance services including the provision of emergency and crisis responses; mental health treatment services by public hospitals and community-based teams; mental health services for people in contact with the justice system; and supported accommodation.

Each government has developed an individual implementation plan. These identify actions to be funded and undertaken in each of five areas:

1. promotion, prevention and early intervention

2. integrating and improving the care system

3. participation in the community and employment, including accommodation

In addition, investment has been committed to areas of common action such as: promotion, prevention and early intervention programs; community-based treatment services for people with mental health and drug and alcohol issues; mental health services in rural and remote areas; care coordination; and support for families and carers.

Each government is undertaking different actions as part of its individual implementation plan, reflecting the differences in the range and scale of services that are already in place in each state and territory. In order to ensure maximum effectiveness of the National Action Plan, each state and territory will establish a COAG Mental Health Group. These groups will provide a forum for oversight and collaboration on how the different initiatives from the Australian, state and territory governments will be coordinated and delivered in a seamless way.

This National Action Plan also recognises one of the fundamental problems in mental healthcare; the serious workforce shortage across all mental health professional groups (Productivity Commission 2005). In addition to supporting an enhanced role for GPs in mental healthcare, the plan includes specific actions to increase the specialist mental health workforce. This is essential if care is to be provided for more people, at an earlier stage of their illness, and for the full duration of the time such care is required.

Will this new National Action Plan achieve more than the previous plans? The consideration of mental health by COAG reflected the frustration felt by government – especially the federal government on the apparent lack of progress despite the NMH policy and plans. However, the plan does little to address the discontinuity in care provided to mentally ill people. The Australian government injected funds into those areas for which it has responsibility, and the states and territories into areas for which they have traditionally had responsibility – hospitals and housing/accommodation. Again, while the rhetoric was one of collaboration and alignment, the reality risks continuing the frustration experienced by the consumers of services that are unevenly provided, variably targeted and of uncertain quality.

The injection of additional funds by federal, state and territory governments partly addresses the lack of investment and commitment cited as a major barrier to implementing previous national policy (Groom et al. 2003, Mental Health Council of Australia 2005, Thornicroft & Betts 2001). Consumer and advocacy groups were quick to point out that the level of investment promised was still insufficient to address the deficiencies which had been highlighted by previous reports. Ensuring that funding continues and grows appropriately will be essential in initiating and maintaining change. However, while funding is a necessary component it will not be sufficient to ensure policy is successfully implemented.

Effective leadership is needed, the target group of consumers for inclusion must be agreed, responsibilities for action must be clear, and services must be coordinated effectively to ensure that people who require treatment get the services they need. Difficult questions must be addressed, including which treatments are appropriate, do those delivering the treatments have the necessary knowledge and skills to provide effective treatment, and are the outcomes of treatment satisfactory. It is to be hoped that the implementation of the National Action Plan will incorporate such areas.

Finally, the plan includes a clear commitment to evaluation of progress. The plan is directed to achieving four key outcomes, and a series of measures have been identified to enable monitoring of progress against outcomes (Box 18.1). All ministers for health will report annually to COAG on implementation of the plan and on progress against these agreed outcomes. An independent evaluation and review of the National Action Plan after 5 years will reveal what and how much has been achieved.

BEYOND NATIONAL MENTAL HEALTH POLICY?

Given the almost universal support for the policy directions included in the NMH Strategy, and apparent commitment by state, territory and federal governments, why is there such disenchantment and disappointment with the progress of mental health reform in Australia?

In part, the answer lies in the rhetoric not being matched by sufficient investment.

However, as noted above, there has also been debate over which types or severity of mental illness should be addressed under the policy – the severely mentally ill, often with chronic or recurring illness (approximately 3% of the population) – or the broader 20% who suffer a mental illness in any 1 year. The reported failings of the National Mental Health Policy and its implementation might in part relate to this confusion of effort. Each of the National Mental Health Plans has tended to broaden the scope of mental health service delivery; from those services directed primarily to those with severe mental illness, to an early intervention and population-based approach.

Mental health policy has also struggled to align the role of service delivery, with the expectations for broader community engagement through employment, social networks and family cohesion. The challenge for government is to reconsider national mental health policy in light of the recognition of the broad requirements for ‘service’ beyond those of ‘health services’, and to develop a set of principles and objectives through which services for those with mental illness can be developed and which allows for improved participation in employment and engagement with all sectors of the community.

An area worthy of discussion is whether a single mental health policy is sufficiently discriminating given the breadth of presentation and service requirements. Perhaps the debate in relation to mental health policy needs to be reconceptualised. To date, national mental health policy and plans have assumed a universal applicability. The refrain of complaint and disenchantment calls for a major rethink of such an approach. There needs to be explicit consideration of the impact on mental illness in policies relating to areas such as housing, employment, justice and education. These areas are beyond ‘health’ but need to be included in mental health policy deliberations. This is not to say that effective professional clinical health services should not remain ‘core business’ in mental health service delivery, but to recognise that good mental health requires attention to a number of other areas relevant to government policy and funding.