CASE 18

Doris is a 25-year-old married black woman. Over the past 6 months she has noticed increasing swelling in her legs with “frothy” dark urine and she has had intermittent severe headaches, unrelated to menses. Despite her and her husband’s wishes, she has been unable to conceive for 5 years and now has had three spontaneous abortions, all in the first 8 to 12 weeks of pregnancy. Query into the family history indicated that she was an adopted child. A detailed analysis of Doris’s serum immunoglobulin, a complete blood cell count, and blood chemistry was ordered. Laboratory results indicated a mild increase in leukocytes, elevated IgG and serum creatinine levels, but a mild thrombocytopenia. Additionally, urinalysis indicated that she was spilling protein in her urine, along with some red cells.

QUESTIONS FOR GROUP DISCUSSION

RECOMMENDED APPROACH

Implications/Analysis of Clinical History

Peripheral Edema

Leg swelling in an otherwise healthy individual should make you wonder about renal problems (see Case 17). In the absence of infection or an obstruction (kidney stone, which generally presents with pain as severe as childbirth labor!), the peripheral edema suggests noninfectious inflammation “higher up” the urinary tract (in the kidney). Immune complex deposition in the glomeruli, with subsequent complement and neutrophil activation, triggers an inflammatory response that leads to a condition known as glomerulonephritis.

Implications/Analysis of Laboratory Investigation

Laboratory results also indicated an elevated serum creatinine level, which suggests that the kidneys are not clearing creatinine efficiently, and this should be followed with a 24-hour urine collection to measure the rate of clearance (see Case 17). Ineffective clearance of creatinine is consistent with immune complex–mediated damage to the kidneys.

The elevated IgG value indicates that there is an ongoing antibody response. In the absence of an infection, this is highly suggestive of an autoimmune (or malignant) disease. The mild lymphopenia and thrombocytopenia are both consistent with the presence of autoantibodies causing lysis of both normal white blood cells and platelets. There is no evidence of anemia (autoantibodies to red cells) and so a Coombs’ test is not necessary (see Case 15).

Additional Laboratory Tests

Kidney Biopsy

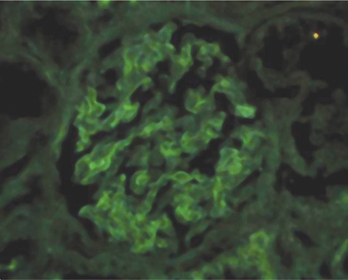

The prognosis regarding kidney function is assessed using a renal (glomeruli) biopsy with immunofluorescence staining (Fig. 18-1). This assay detects immune complexes that have been deposited in the basement membrane and endothelia. You would expect to see bright staining that appears “lumpy and bumpy,” indicating that the detected autoantibodies are part of a preformed immune complex and not simply bound to the basement membrane.

ETIOLOGY: SYSTEMIC LUPUS ERYTHEMATOSUS

SLE is a multisystem/systemic disorder with manifestations in multiple organs/tissues (see Cases 22 and 31). There is a known genetic association with human leukocyte antigens (HLA) DR2/DR3. Further evidence for genetic susceptibility in SLE is the greater concordance in monozygotic (MZ) rather than dizygotic (DZ) twins (30% vs. <10%). There is also a correlation with the complement C2 and C4 genes and tumor necrosis factor (TNF) receptor genes. Presumably (in a multisystem/multigenic disorder) these genes are all implicated at different stages in either the ontogeny of immune development to antigens that are important in the etiology of the disease or in the subsequent inflammatory responses that follow.