CHAPTER 17 The DSM-IV-TR: A Multiaxial System for Psychiatric Diagnosis

DSM-IV-TR IN CONTEXT: AN EVOLVING DIAGNOSTIC SYSTEM

Psychiatric diagnostic classification serves a variety of clinical and other purposes. Diagnosis marks the borders between mental disorders and nondisorders (such as normal personality variations and stressful life problems) and between one type of disorder and another.1 Diagnostic schemata have practical implications for helping clinicians to conceptualize psychiatric issues, to communicate with patients and other clinicians, and, ideally, to make prognostic predictions and to plan effective treatments.2,3 A useful diagnostic system also enables psychiatric research to flourish. It permits valid and reliable classification of patients in clinical research settings and defines practical human problems that may inspire and benefit from basic research efforts. Recorded efforts to document, describe, and classify mental illness go back thousands of years; they include attempts to group diseases by cross-sectional phenomenology, by theories of causation, and, later, by clinical course.4

In the United States, the diagnostic system in widest current use is the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR).5 The DSM has been increasingly disseminated internationally. The World Health Organization’s International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision (ICD-10),6 has also been in wide use in other countries for classifying psychiatric disorders. While the ICD-10 correlates more closely with DSM-IV-TR, the previous version, International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM),7 is still used in the United States for coding purposes within medical billing systems for both psychiatric and nonpsychiatric medical disorders.4

The DSM-IV-TR represents the latest in an ongoing process of change in our psychiatric diagnostic system, with the next major revision, DSM-V, expected to be released in 2010 or thereafter.8 While the original Diagnostic and Statistical Manual: Mental Disorders was published in 1952,9 the transition from the second edition (DSM-II)10 to the third edition (DSM-III)11 represented a particular change in emphasis. Psychodynamic formulations were no longer intrinsic to diagnostic categorization, and the DSM-III was to be considered atheoretical and descriptive in orientation, using a multiaxial system. As subsequent revisions were made,5,12,13 there were increasing efforts to ensure diagnostic reliability and validity, to incorporate research findings, and to gather new information via field trials.3,14–17

THE MULTIAXIAL FORMAT OF DSM-IV-TR

The DSM-IV-TR uses a system of multiaxial assessment to promote evaluation and description of multiple kinds of information (Table 17-1). The multiaxial format succinctly organizes problems that will be both highly relevant and subject to change in the course of treatment. An illustration of one way that clinical material might be recorded in the DSM-IV-TR multiaxial format is provided in Box 17-1, with an example of a 28-year-old woman undergoing psychiatric evaluation. This multiaxial assessment asserts that this patient currently has certain affective, characterological, medical, relational, and environmental difficulties that are substantially impairing function. While the texture of this woman’s individual life story may emerge more clearly from the narrative description, constructing and reviewing the five axes provides a structure that may help the clinician begin to consider medications, psychotherapies, and psychosocial or systemic interventions that could be helpful. Nonetheless, it is up to the psychiatrist in his or her clinical interactions to maintain curiosity about how the problems on each axis are constituted and relate to the others for this patient—how they developed, what meaning may be attached to the problems and their treatment, and how they may be amenable or resistant to change.

| Axis I | Clinical disorders |

| Other conditions that may be a focus of clinical attention | |

| Axis II | Personality disorders |

| Mental retardation | |

| Axis III | General medical conditions |

| Axis IV | Psychosocial/environmental problems |

| Axis V | Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) score |

BOX 17-1 Recording Clinical Material in the Multiaxial Format

Axis I

Axis I contains what the DSM-IV-TR labels “Clinical Disorders”: all psychiatric disorders included in the DSM except for the personality disorders and mental retardation, which are recorded on Axis II (Box 17-2). In addition, Axis I is the location to record “Other Conditions That May Be a Focus of Clinical Attention,” which includes medication side effects and a variety of social and relational problems (Box 17-3). All Axis I diagnoses that are relevant to care should be listed in order of clinical concern, with the most important diagnosis listed first.

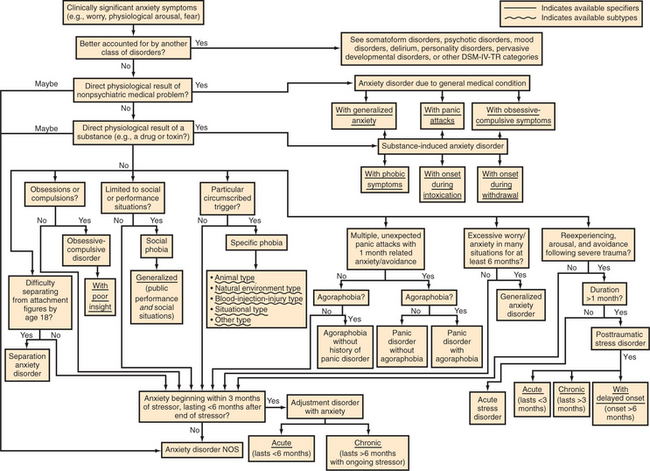

Various algorithms are available to help maneuver through the DSM, including those in Appendix A of the DSM-IV-TR, “Decision Trees for Differential Diagnosis.” An example for the anxiety disorders is shown in Figure 17-1; others are delineated elsewhere in this textbook. When making the determination of which DSM-IV-TR Axis I diagnoses best fit a particular patient, it is important to attend to which diagnoses are hierarchical and mutually exclusive and which may be co-morbid/co-existing in an individual patient at the same time. For example, a patient may have a long-standing specific phobia of heights, develop obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) in adolescence, and then develop post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) following an injury in adulthood, resulting in three co-morbid anxiety disorders at the time of presentation at age 45. On the other hand, the criteria for adjustment disorder clearly state that before assigning this diagnosis, the clinician must determine that the symptoms do not fulfill criteria for another Axis I disorder and are not related to an exacerbation of another Axis I or II disorder. Likewise, a nonpsychiatric medical or substance-induced etiology must typically be ruled out to the clinician’s clinical satisfaction before any other Axis I disorder can be diagnosed.

Most sections of the DSM also include “Not Otherwise Specified (NOS)” diagnoses, such as alcohol-related disorder NOS, dissociative disorder NOS, or eating disorder NOS. When used alone or in combination, these may be used to describe disorders that, although clinically significant, do not fit neatly into the major diagnostic categories, or where more data are required before a more precise diagnosis can be assigned. When applicable, diagnosis deferred, no diagnosis, or unspecified mental disorder (nonpsychotic) could be recorded on Axis I. Another option to signal diagnostic uncertainty is to mark a diagnosis as provisional, meaning that the selected diagnosis is expected to emerge over time or with new information. An example of how Axis I diagnoses may evolve in the setting of clinical uncertainty and change is shown in Box 17-4.

BOX 17-4 Axis I: Diagnostic Evolution over Time

Specifiers may also be added to Axis I diagnoses to provide additional information about the clinical course, features, and severity. Current severity can be indicated with specifiers (i.e., mild, moderate, or severe). When symptoms have substantially improved, the following specifiers may be used: in partial remission, in full remission, or prior history. While guidance is included in the DSM-IV-TR about the definition of these specifiers for some conditions (e.g., conduct disorder, substance dependence, and manic episode), the psychiatrist may apply them to other disorders using his or her clinical judgment. Some disorders have their own specifiers listed in the DSM-IV-TR, such as “with delayed onset” for PTSD. Others have various mutually exclusive subtypes, such as blood-injection-injury type or natural environment type for specific phobia (see Figure 17-1). In some cases, as with mood disorders, the DSM-IV-TR provides instructions for representing specifiers or subtypes via the fifth digit of the ICD-9-CM numerical diagnostic code.

Axis II

Axis II contains personality disorders (Table 17-2) and mental retardation (Table 17-3). Borderline intellectual functioning, although not considered a mental disorder, is also coded on Axis II. As with Axis I, multiple diagnoses should be listed on Axis II if present. If an Axis II diagnosis, rather than one or more co-morbid Axis I disorders, is the primary clinical concern, this may be noted by qualifying it in parentheses as principal diagnosis or reason for visit. Given that additional evaluation time or clinical information may be needed to diagnose Axis II disorders, it may be appropriate to specify no diagnosis or diagnosis deferred. In addition, personality traits that do not meet full criteria for a personality disorder, but are nonetheless maladaptive, may be listed on Axis II without the use of a diagnostic code, as may defensive patterns.4 The DSM-IV-TR provides examples of specific defensive patterns in Appendix B, in the “Glossary of Specific Defense Mechanisms and Coping Styles.” The Defensive Functioning Scale (pp. 807-810)5 is included as a “Proposed Axis for Further Study,” with the suggestion that this hierarchical ranking of defensive styles be placed below Axis V. In practice, inclusion of specific defensive patterns or a defensive level might be more easily incorporated into Axis II.4 Box 17-5 is an example of using Axis II in a way that may enhance clinical communication within a mental health care system.

| Cluster A | Paranoid Personality Disorder |

| Schizoid Personality Disorder | |

| Schizotypal Personality Disorder | |

| Cluster B | Antisocial Personality Disorder |

| Borderline Personality Disorder | |

| Histrionic Personality Disorder | |

| Narcissistic Personality Disorder | |

| Cluster C | Avoidant Personality Disorder |

| Dependent Personality Disorder | |

| Obsessive-Compulsive Personality Disorder | |

| Personality Disorder Not Otherwise Specified | |

Table 17-3 Axis II: Mental Retardation

| Severity | Intelligence Quotient (IQ) |

|---|---|

| Borderline Intellectual Functioning (not considered a disorder but may be coded on Axis II) | 71-84 |

| Mild Mental Retardation | 50-55 to 70 |

| Moderate Mental Retardation | 35-40 to 50-55 |

| Severe Mental Retardation | 20-25 to 35-40 |

| Profound Mental Retardation | Less than 20-25 |

| Severity Unspecified | Unknown |

Axis III

Axis III lists all relevant “General Medical Conditions,” meaning nonpsychiatric illnesses; Table 17-4 lists some of the disorders commonly recorded on this axis. ICD-9-CM codes for frequently used medical diagnoses can be found in Appendix G of the DSM-IV-TR.5 If the evaluator considers the medical problem and psychiatric problem to be closely interrelated, listings on both Axis I and Axis III may be appropriate (Box 17-6). This may occur when the medical problem is thought to cause the psychiatric problem, resulting in a diagnosis of “Psychiatric Disorder due to a General Medical Condition” on Axis I. It may also occur when an Axis I or II psychiatric disorder, subthreshold symptoms (e.g., anxiety or overeating), personality traits or defenses, or physiological stress responses are judged to have a negative impact on the course of a general medical condition; this scenario results in a diagnosis of “Psychological Factor Affecting Medical Condition” on Axis I. Particularly salient psychosocial factors that affect coping with medical illness may also be appropriate to list on Axis IV.

| Type | Examples |

|---|---|

| Nervous system | Seizure disorder |

| Multiple sclerosis | |

| Circulatory system | Atrial fibrillation |

| Paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia | |

| Respiratory system | Asthma |

| Pleural effusion | |

| Neoplastic disease | Multiple myeloma |

| Colon cancer | |

| Endocrine system | Diabetes mellitus |

| Hypothyroidism | |

| Nutritional diseases | Obesity |

| Folic acid deficiency | |

| Metabolic diseases | Hyponatremia |

| Hemochromatosis | |

| Digestive system | Constipation |

| Chronic pancreatitis | |

| Genitourinary system | Acute renal failure |

| Renal calculus | |

| Hematological system | Iron-deficiency anemia |

| Agranulocytosis | |

| Eye | Glaucoma |

| Cataract | |

| Ear, nose, and throat | Chronic sinusitis |

| Hearing loss | |

| Musculoskeletal system | Osteoporosis |

| Systemic lupus erythematosus | |

| Cutaneous system | Psoriasis |

| Decubitus ulcer | |

| Congenital syndromes | Fetal alcohol syndrome |

| Spina bifida | |

| Pregnancy-related diseases | Hyperemesis gravidarum |

| Preeclampsia | |

| Infectious diseases | Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus |

| Syphilis | |

| Medication overdose | Imipramine overdose |

| Acetaminophen overdose |

Axis IV

Psychosocial and environmental problems are listed on Axis IV (Table 17-5).18 As many stressors as are relevant to diagnosis and clinical management may be included. In some treatment settings, a checklist that contains common types of problems that has space for adding specifics, such as the one contained in the DSM-IV-TR “Multiaxial Evaluation Report Form” (p. 36),5 can be useful in facilitating clinical communication. Much of the time, Axis IV will include only current problems, but in some cases, past stressors are particularly relevant to diagnosis and clinical management and should be listed as well. For example, though it occurred several years previously, a contentious parental divorce that has exacerbated a teenager’s anxiety disorder and is critical to understanding the current family environment should be included on Axis IV, with the anxiety disorder listed as usual on Axis I. Sometimes the psychosocial or environmental problem is important as a main target of treatment, rather than primarily via its effects on a separate psychiatric disorder; in this case, the problem may also be listed on Axis I, using a code from the category “Other Conditions That May Be the Focus of Clinical Attention” (Box 17-7).

| Problem | Examples |

|---|---|

| Primary support group | Death of parent |

| Divorce | |

| Physical abuse | |

| Social environment | Loss of support due to migration |

| Best friend moved away | |

| Educational | School failure |

| Peer teasing interfering with learning | |

| Occupational | Frequent shift change |

| Unemployment | |

| Difficult boss | |

| Housing | Threatened eviction |

| Unsafe neighborhood | |

| Economic | Poverty |

| Financial losses | |

| Health care services | Uninsured |

| No transportation to clinic | |

| Legal | Incarceration |

| Victim of crime | |

| Other psychosocial/environmental | Lost home in flood |

| Conflict with primary care physician |

Axis V

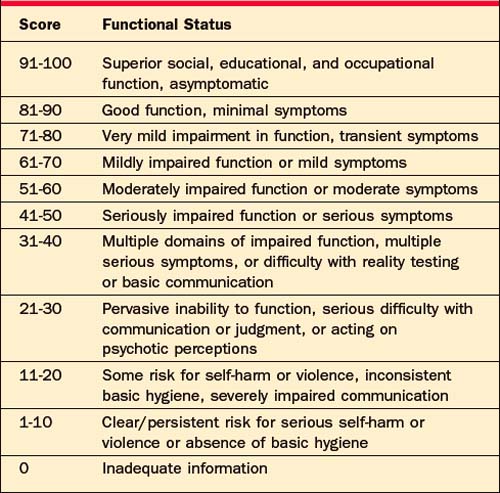

The Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) is recorded on Axis V (Table 17-6).19 The GAF is a number between 0 and 100 that summarizes the clinician’s view of the patient’s current degree of impairment in terms of psychosocial and occupational or educational function. Generally, normal function is coded in the 70-to-100 range, mild psychiatric symptoms fall in the 70-to-80 range, and moderate symptoms are assigned a number between 60 and 70. Severe symptoms are coded as 50 and below; higher levels of psychiatric support (such as intensive community-based treatment, residential settings, or inpatient hospitalization) are often required as function drops further down the scale. Although it may be difficult to determine in complicated cases, the DSM-IV-TR specifies that functional difficulty that results from “physical (or environmental) limitations”5 should not be considered in assigning a GAF score; the intent is to focus on the effects of mental illness. So, a patient who is no longer able to work or to live independently because of paraplegia may nonetheless receive a GAF score well above 70 if he has a wide social network, remains active in local politics, feels satisfied with life, and experiences frustration but takes effective action in the face of setbacks related to his physical problems.

Table 17-6 Axis V: Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) Scale

| Score | Functional Status |

|---|---|

| 91-100 | Superior social, educational, and occupational function, asymptomatic |

| 81-90 | Good function, minimal symptoms |

| 71-80 | Very mild impairment in function, transient symptoms |

| 61-70 | Mildly impaired function or mild symptoms |

| 51-60 | Moderately impaired function or moderate symptoms |

| 41-50 | Seriously impaired function or serious symptoms |

| 31-40 | Multiple domains of impaired function, multiple serious symptoms, or difficulty with reality testing or basic communication |

| 21-30 | Pervasive inability to function, serious difficulty with communication or judgment, or acting on psychotic perceptions |

| 11-20 | Some risk for self-harm or violence, inconsistent basic hygiene, severely impaired communication |

| 1-10 | Clear/persistent risk for serious self-harm or violence or absence of basic hygiene |

| 0 | Inadequate information |

The GAF score is not a static number; it changes for each patient over time. It can be used to track and succinctly communicate the course of psychiatric disorders over time and to monitor response to treatment. An increase in the GAF score from 35 to 55 during the course of an inpatient hospitalization, for example, would suggest that the treatment plan has been at least somewhat effective, whereas a decline from 35 to 20 might suggest that it has not. Reporting the highest and lowest GAF score in the past year along with the current GAF score can also help paint a concise picture of overall function. However, it is important to consider the limitations of the GAF scale in clinical decision-making (Box 17-8). Neither the GAF score alone nor, for that matter, the entire multiaxial assessment can be a substitute for psychiatric clinical skill and judgment.

TOWARD DSM-V: CRITIQUES OF DSM-IV-TR

Already, efforts have begun to consider major and minor improvements that could be incorporated into DSM-V. The American Psychiatric Association, the National Institutes of Mental Health,8 prominent psychiatric journals,20 and scholars working in a variety of areas3,21–27 have all been active in the preparation phase. Appendix B of the DSM-IV-TR itself contains criteria sets and new axes that are under consideration for inclusion in future editions. Additional suggestions for change may reflect current or anticipated advances in psychiatric research, or may appeal to potential refinement in, or addition of, categories based on clinical utility.2 For example, Mayou and colleagues22 propose eliminating the current DSM-IV-TR “Somatoform Disorders” section, distributing these diagnoses and related concerns regarding patients’ interactions with the medical system piecemeal into Axes I, II, III, and IV.22 Pincus and colleagues28 raise the possibility of eliminating the classification of adjustment disorders and regrouping these patients as “subthreshold” variants in other categories, such as anxiety disorders. Other potential reorganizations include listing delusional and nondelusional variants of disorders together; creating a category of obsessive-compulsive spectrum disorders (including OCD, Tourette’s, body dysmorphic disorder, trichotillomania, and/or hypochondriasis); and regrouping the trauma-related disorders.29,30

At the same time, efforts have been made to more radically challenge the “atheoretical” basis of the DSM and to reintroduce explicitly theoretically driven diagnostic schemata to psychiatry. Researchers have suggested the potential of major reclassification of disorders on the basis of underlying pathophysiology, signaled perhaps by response to a common class of psychotropic medications31 or by phenotypes with apparent etiological similarities.32 Follette and Houts33 argue that the underlying theory behind DSM-IV-TR, remaining unstated perhaps for political reasons, is biologically oriented; they propose the development of competing diagnostic systems, to be judged by the degree of scientific advancement they engender. Other writers express ambivalence about the idea of psychiatric diagnosis and the “medical model” altogether, objecting, for example, to potentially counter-therapeutic legal, ethical, social, and economic uses and misuses of diagnostic information both within and outside the mental health treatment relationship.34,35 Brendel36 concurs that the theoretical underpinning of the DSM-IV-TR is at least implicitly biological—for example, in allowing attribution of Axis I disorders to general medical conditions and substances, but not to psychosocial causes. However, he proposes pragmatic and pluralistic solutions to address this concern from within the DSM multiaxial framework in order to “work toward making multi-factorial causation and provisional case formulation as much a part of formal diagnosis as they are of everyday practice” (p. 133).36 Some critiques of DSM-IV-TR from specific theoretical orientations are described next.

Psychodynamic Approaches

One criticism of psychiatric evaluation geared too rigidly to making DSM-IV–based multiaxial diagnosis is that it may neglect psychodynamic formulation, resulting, for example, in the possibility of psychiatrists’ “feeling more confident that they know what the patient ‘has’ than they are of who the patient is” (Gordon and Riess37); in this scenario, there may be difficulty in determining which combinations of biological, spiritual, social, and/or psychological approaches to treatment might be indicated.37 Some have suggested that psychodynamic principles be returned to the DSM. The Defensive Functioning Scale appears in Appendix B as an axis to be studied for potential incorporation into future versions of the DSM, and alternative multiaxial schemas designed for psychotherapy planning have been proposed as well.38 Meanwhile, a coalition of psychoanalytically oriented organizations has developed its own diagnostic manual separate from the DSM and ICD.39

Behavioral Approaches

Behaviorally oriented clinicians argue that describing a behavior (such as crying) divorced from its context and function is meaningless, and that behavioral functional analysis should be incorporated into diagnostic classification.33,40 In this view, the kinds of syndromic disorders created in DSM-IV-TR by grouping together of lists of symptoms is minimally useful. For example, it may be more helpful in behavioral treatment planning to create categories that account for what is reinforcing rule-breaking behavior in a child, rather than listing the types or numbers of rules broken (fire setting vs. lying), to create a category such as “Conduct Disorder.”41

Family/Systems Theory

Despite caveats within the text of the DSM as to the difficulty of satisfactorily defining the boundaries of the term mental disorder, it is clear that this diagnostic system identifies mental disorders as occurring solely “in the individual” (pp. xxx–xxxi).5 Critics operating from a family therapy or systems orientation have questioned this fundamental assumption. The DSM-IV-TR currently allows problematic relationship patterns, while not recognized as mental disorders, to be listed in the multiaxial system. This can be done using items from “Other Conditions That May Be a Focus of Clinical Attention” on Axis I to specify that problems exist in a particular relationship (e.g., “Parent-Child Relational Problem,” or “Partner Relational Problem”). Relational difficulties could also be recognized in a more quantitative manner by using the proposed Global Assessment of Relational Functioning (GARF) Scale from Appendix B as a supplement to Axis V. However, use of these strategies in the absence of an individual disorder listed on Axis I or II may result in the practical problem of difficulty receiving third-party reimbursement for treatment, no matter how impairing the relational difficulties may be for the individuals involved.4 While some have argued that this problem invites increased attention to the limitations of the DSM system or to creating alternative systems of assessment,34,42 others have proposed that disordered family systems could be categorized and operationalized with reliable diagnostic criteria based on research, perhaps becoming included on Axis II or elsewhere within a revised DSM.43,44

Evolutionary/Developmental Approaches

The issue of environmental influence on the individual raises the possibility of reconsidering psychiatric diagnosis from evolutionary, adaptational, and neurodevelopmental perspectives.24,25,45 This issue may be particularly vexing in the area of child psychiatry; while children’s distress may often arise from impaired adaptation, trauma, or a lack of fit between developmental needs and environmental resources, these early experiences may also go on to affect neurobiological development.25 In turn, temperament and biological substrate help shape future experience and the emergence of symptomatology. Knapp and Jensen46 argue that a useful diagnostic scheme for children and adolescents must capture not only symptoms, but also developmental stage and the child’s adaptation to his or her sociocultural context. They suggest adding a Relationship Axis or descriptive material within the DSM text that builds on the Diagnostic Classification of Mental Health and Developmental Disorders of Infancy and Early Childhood.47

Dimensional Models

The introduction to DSM-IV-TR briefly discusses the limitations of the categorical model used to organize the DSM and the possibility of incorporating dimensional approaches in future editions. Despite the clinical and administrative complications that such a major change would likely entail,48 some authors have argued strongly that dimensional models using standardized instruments would aid the field in differentiating pathological from normal psychological function and creating more useful boundaries between conditions. Rather than particular diagnoses, Widiger and Clark3 imagine a revised DSM that would “consist of an ordered matrix of symptom-cluster dimensions.” There has been particular work along these lines in the area of personality disorders research, with various proposed systems of dimensional classification that may rate the degree of traits (such as extroversion, novelty seeking, persistence, mistrust, aggression, and social avoidance).21,44,49

Cultural Models

As the DSM becomes more widely used internationally and there is increasing attention to cultural diversity in the United States, researchers have argued the need to better integrate cultural matters into DSM-V.50 For example, Lewis-Fernández and colleagues51 delineate how the syndrome of ataque de nervios found in many Spanish-speaking cultures both overlaps with and differs from panic disorder, psychiatric disorders that feature dissociative symptoms, and normal reactions to stressful situations. Recognition of this syndrome, and of its inability to be simply “translated” into one of the DSM diagnoses, may have important implications for culturally appropriate treatment. By contrast, depressed Chinese-Americans often have somatic symptoms for a variety of reasons. When asked directly, however, many readily endorse the psychological symptoms of major depressive disorder as defined in the DSM, creating the possibility of negotiating acceptable and effective treatments52; in this scenario, it may be more important to change the delivery of services than to change the diagnostic criteria themselves.

CONCLUSION

A variety of arguments have been made for improving—or even discarding—the multiaxial system of the DSM-IV-TR. It is clear that we must view the current iteration of the DSM as provisional.53 Given the complexity of the human brain and behavior and the variety of natural and social environments in which people live, it is likely that any future psychiatric diagnostic system would also need to be considered provisional: subject to change on the basis of empirical evidence and clinical utility. Nonetheless, the DSM-IV-TR can be powerfully used by clinicians who are attentive to its limitations and who maintain a pragmatic focus on what benefits their individual patients.36,54 The multiaxial diagnostic system provides a framework that can help clinicians to gather and synthesize information systematically and to communicate clearly. A careful multiaxial assessment allows the clinical psychiatrist, and the research community, to proceed beyond the diagnostic purview of the DSM, toward productive treatment.

1 Wakefield JC, First MB. Clarifying the distinction between disorder and non-disorder: confronting the overdiagnosis (false-positives) problem in DSM-V. In: Phillips KA, First MB, Pincus HA, editors. Advancing DSM: dilemmas in psychiatric diagnosis. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association, 2003.

2 First MB, Pincus HA, Levine JB, et al. Clinical utility as a criterion for revising psychiatric diagnoses. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:946-954.

3 Widiger TA, Clark LA. Toward DSM-V and the classification of psychopathology. Psychol Bull. 2000;126:946-963.

4 First MB, Frances A, Pincus HA. DSM-IV-TR guidebook. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing, 2004.

5 American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, fourth edition, text revision. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association, 2000.

6 World Health Organization. International statistical classification of diseases and related health problems, tenth revision. Geneva: World Health Organization, 1992.

7 World Health Organization. International classification of diseases, ninth revision, clinical modification. Ann Arbor, MI: Commission on Professional and Hospital Activities, 1978.

8 Kupfer DJ, First MB, Regier DA, editors. A research agenda for DSM-V. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Association, 2002.

9 American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association, 1952.

10 American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, second edition. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association, 1968.

11 American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, third edition. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association, 1980.

12 American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, third edition, revised. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association, 1987.

13 American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, fourth edition. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association, 1994.

14 Bayer R, Spitzer RL. Neurosis, psychodynamics, and DSM-III: a history of the controversy. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1985;42:187-196.

15 Klerman GL, Vaillant GE, Spitzer RL, et al. A debate on DSM-III. Am J Psychiatry. 1984;141:539-553.

16 Robins E, Guze SB. Establishment of diagnostic validity in psychiatric illness: its application to schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 1970;126:983-987.

17 Kendler K. Toward a scientific psychiatric nosology: strengths and limitations. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1990;47:969-973.

18 Skodol A. Axis IV: a reliable and valid measure of psychosocial stressors? Compr Psychiatry. 1991;32:503-515.

19 Goldman HH, Skodol AE, Lave TR. Revising Axis V for DSM-IV: a review of measures of social functioning. Am J Psychiatry. 1992;149:1148-1156.

20 Editor’s note: new features for readers. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:770.

21 Widiger TA, Simonsen E, Krueger R, et al. Personality disorder research agenda for the DSM-V. J Pers Disord. 2005;19(3):315-338.

22 Mayou R, Kirmayer LJ, Simon G, et al. Somatoform disorders: time for a new approach in DSM-V. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:847-855.

23 Castle DJ, Phillips KA. Obsessive-compulsive spectrum of disorders: a defensible construct? Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2006;40:114-120.

24 Jensen PS, Knapp P, Mrazek DA. Toward a new diagnostic system for child psychopathology: moving beyond the DSM. New York: Guilford Press, 2006.

25 Jensen PS, Mrazek DA. Introduction. In: Jensen PS, Knapp P, Mrazek DA, editors. Toward a new diagnostic system for child psychopathology: moving beyond the DSM. New York: Guilford Press, 2006.

26 O’Brien CP, Volkow N, Li TK. What’s in a word? Addiction versus dependence in DSM-V. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:764-765.

27 Tsuang MT, Stone WS, Tarbox SI, et al. Insights from neuroscience for the concept of schizotaxia and the diagnosis of schizophrenia. In: Phillips KA, First MB, Pincus HA, editors. Advancing DSM: dilemmas in psychiatric diagnosis. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Association, 2003.

28 Pincus HA, McQueen LE, Elinson L. Subthreshold mental disorders: nosological and research recommendations. In: Phillips KA, First MB, Pincus HA, editors. Advancing DSM: dilemmas in psychiatric diagnosis. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association, 2003.

29 Phillips KA, Price LH, Greenberg BD, et al. Should the DSM diagnostic groupings be changed? In: Phillips KA, First MB, Pincus HA, editors. Advancing DSM: dilemmas in psychiatric diagnosis. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association, 2003.

30 Phillips KA, First MB, Pincus HA, editors. Advancing DSM: dilemmas in psychiatric diagnosis. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association, 2003.

31 Hudson JI, Pope HG. Affective spectrum disorder: does antidepressant response identify a family of disorders with a common pathophysiology? Am J Psychiatry. 1990;147:552-564.

32 McHugh PR. Stiving for coherence: psychiatry’s efforts over classification. JAMA. 2005;293(20):2526-2528.

33 Follette WC, Houts AC. Models of scientific progress and the role of theory in taxonomy development: a case study of the DSM. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1996;64:1120-1132.

34 Eriksen K, Kress VE. Beyond the DSM story: ethical quandaries, challenges, and best practices. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 2005.

35 Szasz TS. Liberation by oppression: a comparative study of slavery and psychiatry. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers, 2002.

36 Brendel DH. Healing psychiatry: bridging the science/humanism divide. Cambridge: MIT Press, 2006.

37 Gordon C, Riess H. The formulation as a collaborative conversation. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2005;13:112-123.

38 Mezzich JE, Schmolke MM. Multiaxial diagnosis and psychotherapy planning: on the relevance of ICD-10, DSM-IV and complementary schemas. Psychother Psychosom. 1995;63:71-80.

39 PDM Task Force. Psychodynamic diagnostic manual. Silver Spring, MD: Alliance of Psychoanalytic Organizations, 2006.

40 Follette WC. Introduction to the special section on the development of theoretically coherent alternatives to the DSM system. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1996;64:1117-1119.

41 Scotti JR, Morris TL, McNeil CB, et al. DSM-IV and disorders of childhood and adolescence: can structural criteria be functional? J Consult Clin Psychol. 1996;64:1177-1191.

42 Ivey AE, Ivey BB. Toward a developmental diagnostic and statistical manual: the vitality of a contextual framework. J Counsel Dev. 1999;77:484-491.

43 Reiss D, Emde RN. Relationship disorders are psychiatric disorders: five reasons they were not included in DSM-IV. In: Phillips KA, First MB, Pincus HA, editors. Advancing DSM: dilemmas in psychiatric diagnosis. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association, 2003.

44 First MD, Bell CC, Cuthbert B, et al. Personality disorders and relational disorders: a research agenda for addressing crucial gaps in DSM. In: Kupfer DJ, First MB, Regier DA, editors. A research agenda for DSM-V. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association, 2002.

45 Pine DS, Alegria M, Cook EH, et al. Advances in developmental science and DSM-V. In: Kupfer DJ, First MB, Regier DA, editors. A research agenda for DSM-V. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association, 2002.

46 Knapp P, Jensen PS. Recommendations for DSM-V. In: Jensen PS, Knapp P, Mrazek DA, editors. Toward a new diagnostic system for child psychopathology: moving beyond the DSM. New York: Guilford Press, 2006.

47 Zero to Three: National Center for Infants, Toddlers, and Families. Diagnostic classification of mental health and developmental disorders of infancy and early childhood (DC:0-3). Arlington, VA: Zero to Three: National Center for Infants, Toddlers, and Families, 1994.

48 First MB. Clinical utility: a prerequisite for the adoption of a dimensional approach in DSM. J Abnorm Psychol. 2005;114(4):560-564.

49 Livesley WJ. Diagnostic dilemmas in classifying personality disorder. In: Phillips KA, First MB, Pincus HA, editors. Advancing DSM: dilemmas in psychiatric diagnosis. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association, 2003.

50 Alarcón RD, Bell CC, Kirmayer LJ, et al. Beyond the funhouse mirrors: research agenda on culture and psychiatric diagnosis. In: Kupfer DJ, First MB, Regier DA, editors. A research agenda for DSM-V. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association, 2002.

51 Lewis-Fernández R, Guarnaccia PJ, Patel S, et al. Ataque de nervios: anthropological, epidemiological, and clinical dimensions of a cultural syndrome. In: Georgiopoulos AM, Rosenbaum JF, editors. Perspectives in cross-cultural psychiatry. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2005.

52 Yeung A, Kim R. Illness beliefs of depressed Chinese American patients in a primary care setting. In: Georgiopoulos AM, Rosenbaum JF, editors. Perspectives in cross-cultural psychiatry. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2005.

53 Hyman SE. Foreword. In: Phillips KA, First MB, Pincus HA, editors. Advancing DSM: dilemmas in psychiatric diagnosis. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association, 2003.

54 Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Skodol AE, et al: DSM-IV-TR casebook: a learning companion to the diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, fourth edition, text revision, Arlington, TX, 2002, American Psychiatric Publishing.