CHAPTER 17

Rotator Cuff Tear

Definition

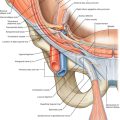

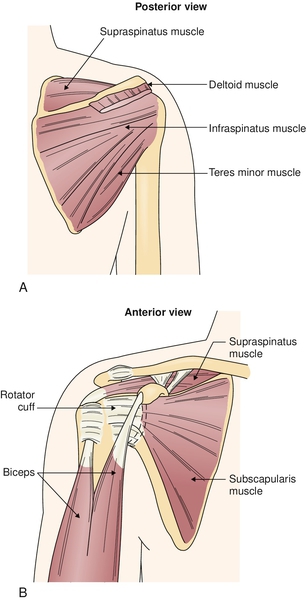

The rotator cuff has three main functions in the shoulder. It compresses the humeral head into the fossa, increases joint contact pressure, and centers the humeral head on the glenoid. Three types of tears can occur to the rotator cuff. A full-thickness tear can be massive and cause immediate functional impairments. Another type of tear, a partial-thickness tear, can be broken down into a tear on the superior surface into the subacromial space or a tear on the inferior surface on the articular side. As a result of a rotator cuff tear, the humeral head will be displaced superiorly during abduction because of the unopposed action of the deltoid. These tears can be either traumatic or degenerative [1–7] (Figs. 17.1 to 17.3).

Traumatic tears occur in the younger population of athletes and laborers, whereas degenerative tears occur in older individuals. One reason that rotator cuff tears are more common in men is because there are more male heavy laborers. The incidence of degenerative tears is increased in both sexes for individuals older than 35 years and for those with chronic impingement syndrome, repetitive microtrauma, tendon degeneration, and hypovascularity [4,6,8].

Symptoms

Symptoms are similar to those of rotator cuff tendinitis. Pain is referred to the lateral triceps and sometimes more globally in the shoulder. There is often coexisting inflammation, and the pain quality is dull and achy. Weakness occurs because of the pain, which is caused by the impaired motion or the tear itself. Persons have difficulty with overhead activities. Patients may report pain at night in a side-lying position.

Physical Examination

Examination is essentially the same as for rotator cuff tendinitis. The most common physical findings of a tear are supraspinatus weakness, external rotator weakness, and impingement. The arm drop test may demonstrate greater weakness than expected from an inflamed, intact tendon, although one can be easily fooled. As with rotator cuff tendinitis, an anesthetic injection into the subacromial space may help discern tear. Even though the pain may be improved or resolved from the injection, resisted abduction will be just as weak because the torn tendon cannot withstand the stress [9].

Remember to examine the cervical spine to avoid missing underlying pathologic changes. A rotator cuff tear develops in some individuals as a result of a radiculopathy or other nerve impairment. The dysfunction of the shoulder from a radiculopathy or suprascapular neuropathy results in weakness of the rotator cuff or the scapular stabilizers. This dysrhythmia causes impingement of the tendons with other structures and eventually leads to fraying and tearing [10–12].

Functional Limitations

The greatest limitation that patients complain of is performing overhead activities [2,7,13–15].

Patients with rotator cuff tendinitis complain of difficulty with overhead activities (e.g., throwing a baseball, painting a ceiling), greatest above 90 degrees of abduction, secondary to pain or weakness. Internal and external rotation may be compromised and may affect daily self-care activities. Women typically have difficulty hooking the bra in back. Work activities, such as filing, hammering overhead, and lifting, will be affected. The patient can be awakened by pain in the shoulder, which impairs his or her sleep.

Diagnostic Studies

The diagnosis of a rotator cuff tear depends mostly on the history and physical examination. However, imaging studies may be used to confirm the clinician’s diagnosis and to eliminate other possible pathologic processes.

Radiographs are often obtained to rule out any osseous problem. A tear can be inferred if there is evidence of humeral head upward migration or sclerotic changes at the greater tuberosity where the tendons insert. Radiographs are helpful with active 90-degree abduction showing a decreased acromiohumeral distance secondary to absence of the supraspinatus and unopposed action of the deltoid.

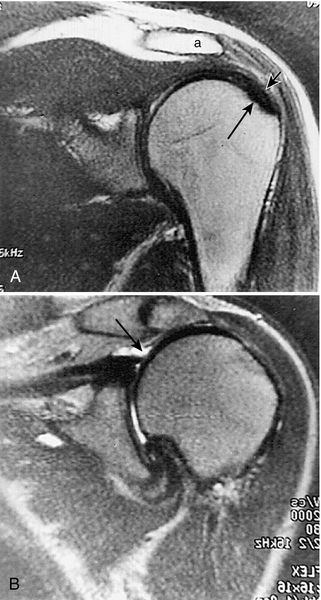

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the shoulder is the “gold standard.” [16] Computed tomographic scans show osseous structures better but are less effective at demonstrating a soft tissue injury. By evaluation of the amount of retraction, the clinician is also better able to predict the course of recovery.

As in the evaluation of a person with rotator cuff tendinitis, an anesthetic injection can be performed to differentiate a tear from tendinitis.

Shoulder arthrography is performed less often since the advent of MRI. Arthrography involves injection of contrast material into the glenohumeral joint followed by plain radiography. Dye should remain contained in the joint space. If it extravasates, this signifies a tear. Partial-thickness rotator cuff tears can be missed, especially tears on the superior surface. Some centers have been combining gadolinium dye injections with MRI. This is used mostly to identify a labral tear, not a rotator cuff tear.

Ultrasound imaging can also be used in the diagnosis of full-thickness rotator cuff tears [17]. Ultrasonography is becoming more popular in the United States, and it can be a very helpful study when it is performed in centers with clinicians who have experience in musculoskeletal ultrasound imaging. It is now believed that ultrasonography is as accurate as MRI in the diagnosis of supraspinatus tendon tears. Full-thickness tears appear hypoechoic or anechoic where fluid has replaced the area of torn tendon. Manual compression will be able to displace the fluid. In an area of torn tendon without fluid, compression will show the “sagging peribursal fat” sign.*

Diagnostic arthroscopy is done in some instances but is not generally necessary.

Treatment

Initial

Initial treatment of a rotator cuff tear is similar to that of rotator cuff tendinitis (see Chapter 16). However, if the symptoms do not respond to a rehabilitation program, the clinician should consider surgical consultation earlier in the course of injury.

Rehabilitation

Because of the interrelationship of instability and impingement previously discussed, there is a great deal of overlap in the rehabilitation of these shoulder problems. Treatment must be individualized and based on the restoration of optimal function, not merely surgical correction of anatomic changes. Supervised physical therapy is the mainstay of treatment and is successful in most patients.

The basic phases of rehabilitation include the following [12]: pain control and reduction of inflammation; restoration of normal shoulder motion, both scapulothoracic and glenohumeral; normalization of strength and dynamic joint stabilization; proprioception and dynamic joint stabilization; and sport-specific training. The rehabilitation phases may overlap and can be progressed as rapidly as tolerated, but all should be performed to speed recovery and to prevent reinjury.

Pain Control and Reduction of Inflammation

Initially, pain control and inflammation reduction are required to allow progression of healing and the initiation of an active rehabilitation program. These can be accomplished with a combination of relative rest, icing (20 minutes, three or four times a day), electrical stimulation, and acetaminophen or a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug. The next section’s rehabilitation program can be added as tolerated by the patient. Having the patient sleep with a pillow between the trunk and the arm will decrease the tension on the supraspinatus tendon and prevent compromise of blood flow in its watershed region.

Restoration of Shoulder Range of Motion

As with all musculoskeletal disorders, the entire body must be taken into consideration. Abnormalities in the kinetic chain can also affect the shoulder. If there are restrictions or limitations in range of motion or strength, the forces will be transmitted to other portions of the kinetic chain, resulting in an overload of those tissues and possibly injury.

After the pain has been managed, restoration of motion can be initiated. The use of Codman pendulum exercises, wall walking, stick or towel exercises, or a physical therapy program is beneficial in attaining full pain-free range. It is important to address any posterior capsular tightness because this can cause anterior and superior humeral head migration, resulting in impingement. A tight posterior capsule and the imbalance it causes force the humeral head anteriorly, producing shearing of the anterior labrum and causing an additional injury. Stretching of the posterior capsule is a difficult task. The horizontal adduction that is usually performed tends to stretch the scapular stabilizers rather than the posterior capsule. If care is taken to fix and to stabilize the scapula and therefore to prevent the stretching of the scapulothoracic stabilizers, stretching of the posterior capsule can be achieved. The focus of treatment in this early stage should be on improving range and flexibility of the posterior capsule, improving postural biomechanics, and restoring normal scapular motion.

Initially, ultrasound to the posterior capsule followed by gentle, passive prolonged stretch may be needed. The use of ultrasound should be closely monitored to prevent heating of an inflamed tendon, which will worsen the injury.

Postural biomechanics are important because with poor posture (e.g., excessive thoracic kyphosis and protracted shoulders), there is increased outlet narrowing, resulting in greater risk for rotator cuff impingement. Restoration of normal scapular motion is also essential because the scapula is the platform on which the glenohumeral joint rotates [20,21]. Thus, an unstable scapula can secondarily cause glenohumeral joint instability and resultant impingement. Scapular stabilization includes exercises such as wall pushups and biofeedback (visual and tactile).

Strengthening

The third phase of treatment is strengthening, and it should be performed in a pain-free range. Strengthening should begin with the scapulothoracic stabilizers and the use of shoulder shrugs, rowing, and pushups, which will isolate these muscles and help return smooth motion, allowing normal rhythm between the scapula and the glenohumeral joint. This will also provide a firm base of support on which the arm can move. Attention should then be turned toward strengthening of the rotator cuff muscles. Positioning of the arm at 45 and 90 degrees of abduction for exercises prevents the “wringing out” phenomenon that hyperadduction can cause by stressing the tenuous blood supply to the tendon of the exercising muscle. The thumbs down position with the arm in greater than 90 degrees of abduction and internal rotation should also be avoided to minimize subacromial impingement. After the scapular stabilizers and rotator cuff muscles are rehabilitated, the prime movers should be addressed to prevent further injury and to facilitate return to prior function.

There are many ways by which to strengthen muscles. The rehabilitation program should start with static contractions and co-contractions, progress to concentric exercises, and be completed with eccentric exercises and endurance training. The BodyBlade (www.BodyBlade.com) can be used for co-contraction in multiple planes and positions for rhythmic stabilization. There are many techniques to strengthen muscles, including static and dynamic exercises. A therapy prescription should include the number of repetitions, the number of sets of repetitions, and the intensity at which the specific exercise should be performed. When strength is restored, a maintenance program should be continued for fitness and prevention of reinjury.

Proprioception

The fourth phase is proprioceptive training. This is important to retrain the neurologic control of the strengthened muscles in providing improved dynamic interaction and coupled execution of tasks for harmonious movement of the shoulder and arm. Tasks should begin with closed kinetic chain exercises to provide joint stabilizing forces. As the muscles are reeducated, exercises can progress to open chain activities that may be used in specific sports or tasks. Exercises such as those using the BodyBlade or plyometrics will also address proprioception. In addition, proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation is designed to stimulate muscle-tendon stretch receptors for reeducation. Kabat [22] has described shoulder proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation techniques in detail.

Task or Sport Specific

The last phase of rehabilitation is to return to task- or sport-specific activities. This is an advanced form of training for the muscles to relearn prior activities. This is important and should be supervised so that the task performed is correct and the possibility of reinjury or injury in another part of the kinetic chain from improper technique is eliminated. The rehabilitation begins at a cognitive level but must be practiced so that it ultimately becomes part of unconscious motor programming.

Procedures

Subacromial injections of anesthetic and corticosteroid may be both diagnostic and therapeutic (see Chapter 16).

Surgery

If the patient’s condition has not progressed with a conservative rehabilitation after 2 to 3 months, a surgical consultation should be considered. If the patient is unable to perform all the activities he or she demands (vocationally and avocationally) after 6 months of treatment and independent exercise performance, a surgical consultation should be obtained. If the patient is a high-level athlete or worker, earlier consultation may be appropriate. The population of younger patients is more amenable to surgical intervention [6,8].

If surgery is contemplated, repair, débridement, decompression, or a combination of these may be considered. A concomitant injury should be considered, such as a labral tear. The detail of these surgical procedures is beyond the scope of this text.

Potential Disease Complications

Partial rotator cuff tears can progress to full-thickness tears, especially if untreated. Rehabilitation attempts to restore biomechanics close to normal to prevent excessive wear on the tendon, which can cause further degeneration. Chronic untreated rotator cuff tears can lead to shoulder arthropathy [6,11].

Potential Treatment Complications

Analgesics and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs have well-known side effects that most commonly affect the gastric, hepatic, and renal systems. There are minimal disadvantages to coordinating a rehabilitation program that may improve the patient’s symptoms to a level at which the patient is satisfied and functional. However, an overly aggressive program can progress a partial tear to a complete tear. With surgery, in general, the potential problems include bleeding, infection, worsening of the complaints, and nerve injury.