Medications for Pain Management and Anesthesia

Objectives

1. Explain why there are so many rules about how opioids and related analgesic drugs may be given.

2. Compare and contrast drug tolerance and drug addiction.

3. List behavior that would make the nurse believe a patient is addicted to a drug.

5. List medications commonly used for the treatment of moderate to severe pain.

6. Identify common methods of local and regional anesthesia.

Key Terms

acute pain (ă-KYŪT PĀN, p. 299)

addiction (ă-DĬK-shŭn, p. 300)

anesthesia (ANN-ess-THEE-zee-uh, p. 309)

chronic pain (KRŎN-ĭk PĀN, p. 299)

dependence (dē-PĔN-dĕns, p. 300)

hydration (hī-DRĀ-shŭn, p. 306)

miosis (mī-Ō-sĭs, p. 300)

opioids (Ō-pē-ŏydz, p. 298)

pain (PĀN, p. 299)

tolerance (TŎL-ŭr-ŭns, p. 300)

withdrawal symptoms (p. 300)

Overview

![]() http://evolve.elsevier.com/Edmunds/LPN/

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Edmunds/LPN/

There are many nerve paths that carry the sensation of pain from an injured part of the body to the brain. This means that there are several different places to block the feeling of pain. Some feelings of pain may be treated by exercise, heat, ice, or other methods. Some pain is so severe that it requires drug treatment. There are now a wide range of drugs used in controlling pain. The most common drugs for mild pain relief include over-the-counter analgesics such as aspirin and acetaminophen. (These drugs are described separately in Chapter 18 because they also have actions other than pain reduction.) Many of the drugs used for treating severe pain are opioids. (An opioid is any substance that produces stupor associated with analgesia, and are used to treat severe pain.) Natural opioids come from opium, which comes from unripe seed capsules of the poppy plant. Opium contains many chemicals, including morphine and codeine. (Heroin is diacetylmorphine, which chemically breaks down into morphine.) Opioid medications interact with specific receptors in the brain and spinal cord to reduce pain. There are also nonopioid analgesics that produce moderate pain relief for conditions not severe enough to require an opioid.

In addition to natural opioids, artificial or synthetic opioids have been developed. It was hoped that many of these new drugs would not be as addictive as morphine, but this was not so. However, these new drugs are useful for pain management and to reverse the effects of opioids. Many of these new drugs are made by changing morphine chemically. Morphine is the basic chemical from which the synthetic opioid analgesics hydrocodone, hydromorphone, and oxycodone have developed. Other classes of synthetic opioids are made of different chemicals but have actions similar to morphine.

Analgesics used in pain management are classified according to their mechanism of action. Opioids are classified as agonist, partial agonist, or agonist-antagonist medications. The term agonist means “to do”; the term antagonist means “to block.” An agonist drug binds with the receptors to activate and produce the maximum response of the individual receptor. A partial agonist produces a partial response of this type. An opioid agonist-antagonist drug produces mixed effects, acting as an agonist at one type of receptor and as a competitive antagonist at another type of receptor. This information is key to understanding the rest of the chapter. Refer back here if needed.

The mechanism of action for opioids is determined by where they bind to specific opioid receptors inside and outside the central nervous system (CNS). There are six types of opioid receptors (delta, epsilon, kappa, mu [types one and two], and sigma). These receptors are responsive to the opiates (have opiate receptors) in each of these areas that interact with autonomic nervous system nerves that carry pain messages (including the release of neurotransmitters), and this interaction produces changes in the person’s reaction to pain. Some opioids block a particular receptor; others stimulate a particular receptor. Although analgesia can occur with the stimulation of delta, epsilon, and kappa receptors, most action occurs at the mu and kappa receptors. Mu receptors produce analgesia, respiratory depression, sedation, euphoria, decreased gastrointestinal (GI) motility, and constricted pupils (miosis). These mu receptors may also lead to physical dependence. Kappa receptors produce analgesia, sedation, and are also associated with decreased GI motility and miosis. Sigma receptors seem to produce mostly unwanted effects.

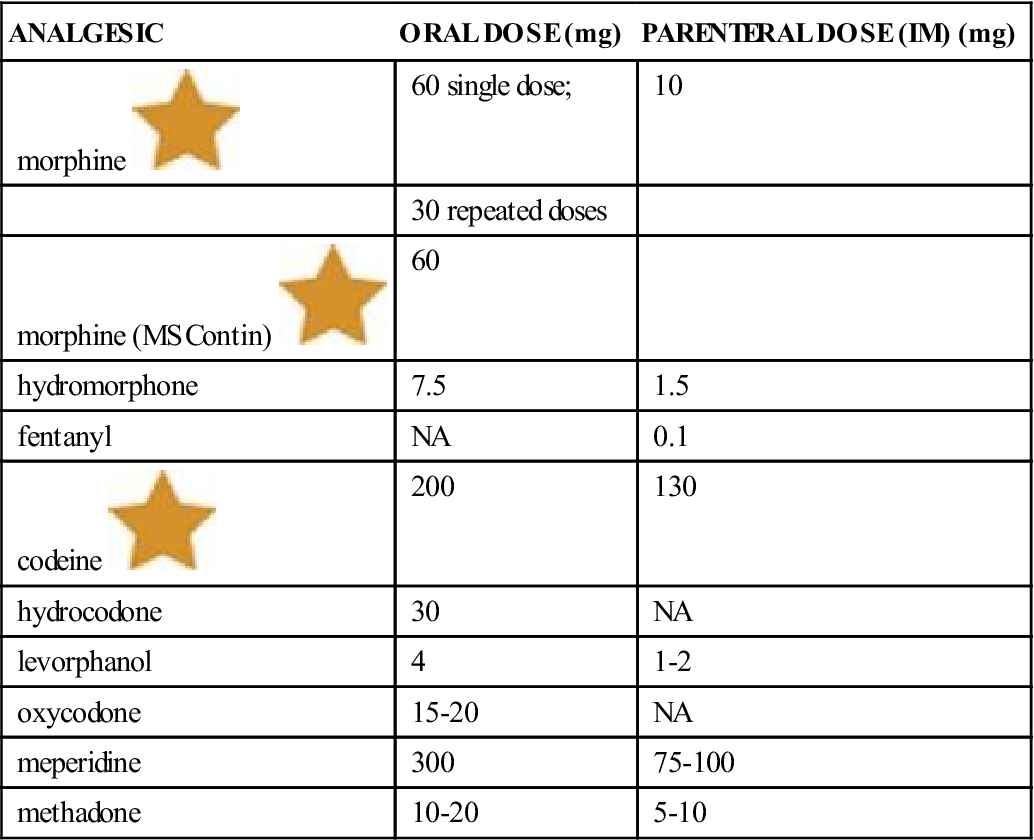

Morphine is the main opioid agonist drug with which all other pain management drugs are compared (Table 17-1). It is used a great deal in acute care and also in hospice settings for dying patients who have severe pain. Codeine, hydrocodone (Hydromet), and oxycodone (OxyContin) are often used in combination with acetaminophen in the outpatient setting. Hydromorphone (Dilaudid) is very potent (with regard to the number of milligrams that are equivalent to morphine) and is only used for treating severe pain not relieved by morphine. It comes as a powder for compounding as well as a tablet.

![]() Table 17-1

Table 17-1

Equivalent Doses of Opioid Analgesics Compared with Morphine 10 mg PO and IM

| ANALGESIC | ORAL DOSE (mg) | PARENTERAL DOSE (IM) (mg) |

| morphine |

60 single dose; | 10 |

| 30 repeated doses | ||

| morphine (MS Contin) |

60 | |

| hydromorphone | 7.5 | 1.5 |

| fentanyl | NA | 0.1 |

| codeine |

200 | 130 |

| hydrocodone | 30 | NA |

| levorphanol | 4 | 1-2 |

| oxycodone | 15-20 | NA |

| meperidine | 300 | 75-100 |

| methadone | 10-20 | 5-10 |

IM, Intramuscular; IV, intravenous; NA, not applicable.![]() Indicates “Must-Know Drugs,” or the 35 drugs most prescribers use.

Indicates “Must-Know Drugs,” or the 35 drugs most prescribers use.

Modified from Brunton L, Lazo L, Parker K, editors: Goodman and Gilman’s pharmacological basis of therapeutics, ed 11, New York, 2005, McGraw-Hill.

Opioid agonist-antagonist drugs may be preferred over opioid agonists for use in patients in the community because their risk for abuse is less. A common drug, pentazocine (Talwin) which is estimated to be about 1/6 as potent as morphine has limited use because of its CNS toxicity. In efforts to limit the abuse of these drugs, the federal government created many regulations that describe who may prescribe or administer opioids. Nurses learn and follow these rules. The nurse may have responsibility for keeping opioids in a safe place, typically a locked cabinet, and account for their use in the hospital or nursing home setting.

This chapter is divided into three sections. The first section deals with opioid agonist analgesics. The second section presents opioid agonist-antagonist analgesics. Nonopioid (centrally acting) combination drug analgesics are presented in the third section.

Pain as A Process

Pain is defined by the International Association for the Study of Pain as an unpleasant sensation or emotion that produces or might produce tissue damage. Pain is always subjective; that is, pain is something the patient feels and that cannot be felt or measured by someone else.

Researchers believe four things are required for pain to occur:

1. An unpleasant stimulus affects nerve endings and sets off electrical activity.

Anxiety, depression, fatigue, and other chronic diseases may increase the perception of pain. Activities designed to distract the patient, create positive attitudes, or provide support may reduce the perception of pain. There are many nondrug methods for doing this. Some of these activities might involve listening to music, massage therapy, cold or hot packs, hydrotherapy, acupuncture, biofeedback, relaxation therapy, art therapy, hypnosis, therapeutic touch, Qigong or Reiki energy therapies, or use of transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) units. Sometimes pain requires nerve blocks or surgical intervention to relieve pain on nerves or structures.

Tolerance, Dependence, and Addiction

Tolerance is a drug-related problem that is seen when the same amount of drug produces less effect over time. In the case of pain, more drug is needed for relief. Dependence is a state in which the body shows withdrawal symptoms when the drug is stopped or a reversing drug or antagonist is given. Withdrawal symptoms are changes in the body or mind, such as nausea or anxiety, that occur when a drug is stopped or reduced after regular use. Tapering off (slowly taking less of the drug) can reduce withdrawal symptoms. Psychologic dependence, or addiction, is the desperate need to have and use a drug for a nonmedical reason and patients have a limited ability to control their drug use. Tolerance and dependence result from regular use of an opioid for a certain length of time and should not be confused with or labeled as addiction. Addiction is a problem; however, a patient in pain should not be denied pain relief because of fear of addiction. All opioid drugs have the potential to cause tolerance and dependence when taken on a long term basis. This is not the same as abuse.

Opioid Agonist Analgesics

Overview

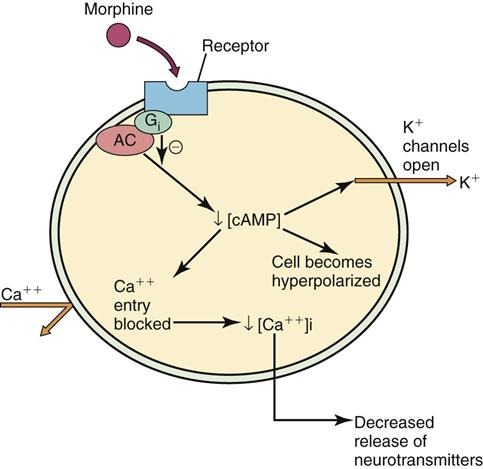

Drugs called opioid agonist analgesics are thought to prevent painful feelings in the CNS (in the substantia gelatinosa [gray matter] of the spinal cord, brain stem, reticular formation, thalamus, and limbic system). (See Chapter 16 for additional information on receptors and neurotransmitters in the CNS.) Figure 17-1 demonstrates how opioids act on neurons.

Action

Opioid agonists bind to opioid receptors. The opioid action of the drug in the CNS is shown through pain relief (analgesia), sleepiness, euphoria (feeling of well-being), unclear thinking, slow breathing, miosis (the pupil of the eye constricts or gets smaller), slowed peristalsis (slowing of the action of smooth muscle in the bowel) causing constipation, reduced cough reflex, and hypotension (low blood pressure).

Uses

Opioid agonist analgesics are used to treat moderate to severe acute pain and chronic pain. They may be used preoperatively to treat pain from injury or other diseases processes; for people who are addicted to opioids (methadone only); for constant cough (codeine); postoperatively for pain; and for labor.

These products are also commonly available as combination products along with medications such as acetaminophen, aspirin, caffeine, and barbital. These allow a small dose of opioid to be combined with other chemicals to relieve symptoms or calm the patient.

Adverse Reactions

Adverse reactions to opioid agonist analgesic drugs include bradycardia (slow heartbeat), hypotension, anorexia (lack of appetite), constipation, confusion, dry mouth, euphoria (excessive happiness), fainting, vomiting, pruritus (itching), skin rash, slow breathing, and shortness of breath. Overdosage may cause bradypnea (very slow breathing, with a rate less than 12 breaths/minute); irregular, shallow breathing; sedation; coma; miosis; cyanosis (blue color to the skin); gradual drop in blood pressure; oliguria (reduced ability to form and pass urine); clammy skin; and hypothermia (abnormally low body temperature). Chronic overdosage symptoms seen in drug abusers include very small pupils, constipation, mood changes, and reduced level of alertness. For IV drug users, there may also be skin infections, pruritus, needle scars, and abscesses. Respiratory rate and sleepiness are the variables most closely watched for signs of overdosage.

Drug Interactions

The CNS depressant effects of opioid agonist analgesics may be increased by the use of other opioid agonist analgesics, alcohol, antianxiety agents, barbiturates, anesthetics, nonbarbiturate sedative-hypnotics, phenothiazines, skeletal muscle relaxants, and tricyclic antidepressants. Opioids act with many other medications to increase or decrease their effects. It is important to identify other medications that the patient is taking prior to starting opioid analgesics.

Nursing Implications and Patient Teaching

Nursing Implications and Patient Teaching

n Assessment

Before a patient can be effectively helped with pain relief, it is important to determine the cause of the pain. Some organizations have called for pain assessment to be the fifth vital sign, but this is not universally accepted. Do not simply administer drugs prescribed for pain without understanding the source of the particular pain. Even in a patient with terminal cancer, evaluate each new pain for a specific cause that may be specifically treated. For example, bone pain can often be managed by radiation. Table 17-2 lists the classifications of pain and their characteristics.

Table 17-2

| CATEGORY | CHARACTERISTICS | EXAMPLE |

| Nociceptive | Somatic Well localized Dull, aching, or throbbing |

Laceration, fracture, cellulitis, arthritis |

| Visceral | Poorly localized Continual aching Referred to dermatomal sites that are distant from the source of the pain |

Subscapular pain arising from diaphragmatic irritation; right upper quadrant pain arising from stretching of liver capsule |

| Neuropathic | Shooting or stabbing pain superimposed over a background of aching and burning | Postherpetic neuralgia, postthoracotomy neuralgia, poststroke pain, trigeminal neuralgia, diabetic polyneuropathy |

Modified from McKenry LM, Tessier E, Hogan MA: Mosby’s pharmacology in nursing, ed 22, St Louis, 2006, Mosby.

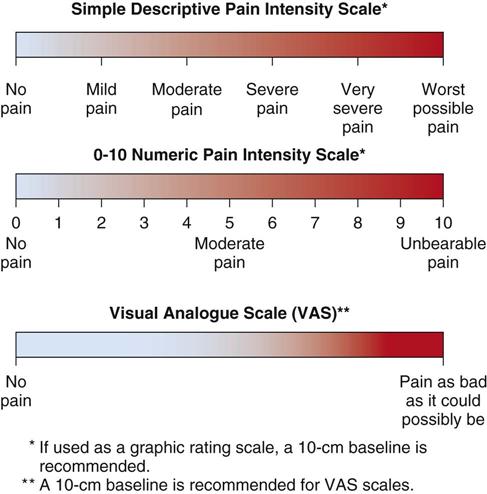

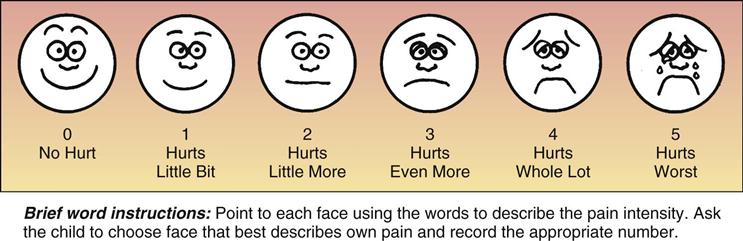

When assessing pain, ask the patient to describe the pain. Learn the history of the pain, including when it started, where it is, what it feels like, how often it occurs, and what makes it worse or relieves it. Accept that patients have pain when they say they have it at the intensity level they say it is. Use a pain scale to make the assessment more objective. In addition to what patients say, the nurse may also sometimes see changes in their breathing, blood pressure, and pulse, as well as tense muscles, sweating, and pupil reaction. Also, they may be restless, crying, or moaning.

Learn as much as possible about other parts of the health history, such as whether the patient has a history of allergic or adverse reaction to morphine or related drugs, past ability to deal with pain, and whether there is any reason to think opioid abuse might become a problem.

The Agency for Health Care Policy and Research Clinical Practice Guidelines include the following principles of pain assessment (A-A-B-C-D-E-E):

Assess pain systematically. Use pain intensity scales (Figures 17-2 and 17-3).

Believe the patient and family in their reports of pain and what relieves it.

Deliver interventions in a timely, logical, and coordinated fashion.

Empower patients and their families.

Enable them to control their course to the greatest extent possible.

n Diagnosis

Are there reasons the patient should not use these medications? Are there risk factors for their use? Is the nurse aware of other things that might pose a problem for a patient taking these medications? Report any problems discovered to the registered nurse or physician.

n Planning

Whenever possible, pain treatment should begin with simple and nonopioid analgesics and supportive pain-relief measures first. These measures are described later.

Remember that pain relief is best if the drug is given before the patient has intense pain.

The main problem in using opioids, especially when the patient is at home where they control their own medicines and not in a hospital, is the risk of physical and psychologic addiction or dependence for the patient. Use caution when opioids are given to older adults, to pregnant women, to physically weak patients, to patients in shock or those who have consumed alcohol, and to children or newborns.

Nonpharmacologic treatment of pain can be used alone or in combination with medications. This type of treatment includes patient education, management of anxiety and depression, cognitive-behavioral therapy, and appropriate exercise and activity. Complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) therapies may be helpful, although there is little scientific evidence to support the use of chiropractic manipulation, homeopathy, and spiritual healing. Heat, ice, massage, topical analgesics, acupuncture, and TENS may provide relief alone or in combination with analgesic medications. Guided imagery and distraction are especially good in pediatric patients.

n Implementation

Because these drugs are often abused, there are many rules related to giving opioid analgesics. The nurse should learn and follow the laws that tell what to do when giving opioid agonist analgesics. The Controlled Substances Act of 1970 (see Chapter 3) classified the opioid agonist analgesics by their potential for abuse. The rules are strict to help prevent people from easily abusing these drugs.

Once the opioid agonist analgesic is metabolized by the body, pain returns, and the patient may then complain of even more pain. This is why these patients often need regular doses of medication before the actions of the previous dose are gone. To prevent respiratory depression (severe slowing of breathing) from the opioids, the drugs should also be given no less than 2 hours before a baby is delivered or before surgery.

The cough reflex is reduced by many of the opioid analgesics. This may be a problem in patients with lung disease. Opioid analgesics may also produce a faster heart rate in patients who have a particular heart rhythm problem. These drugs may also make convulsions worse in people who have seizures. Opioids may be given orally or rectally, by injection into the muscle, the subcutaneous tissue, directly into the vein, or by epidural or intrathecal (spinal) administration. Sometimes the health care provider also prescribes a range of medicine that might be given. The amount of pain felt by the patient will help the nurse determine the dose of the opioid and how it should be given. Intermittent or patient controlled infusion of opioids into the bloodstream may be required when the patient has pain from terminal cancer or has some other chronic condition that causes severe pain. (Review materials in Chapter 10 related to the patient controlled analgesia [PCA] in hospitalized patients.)

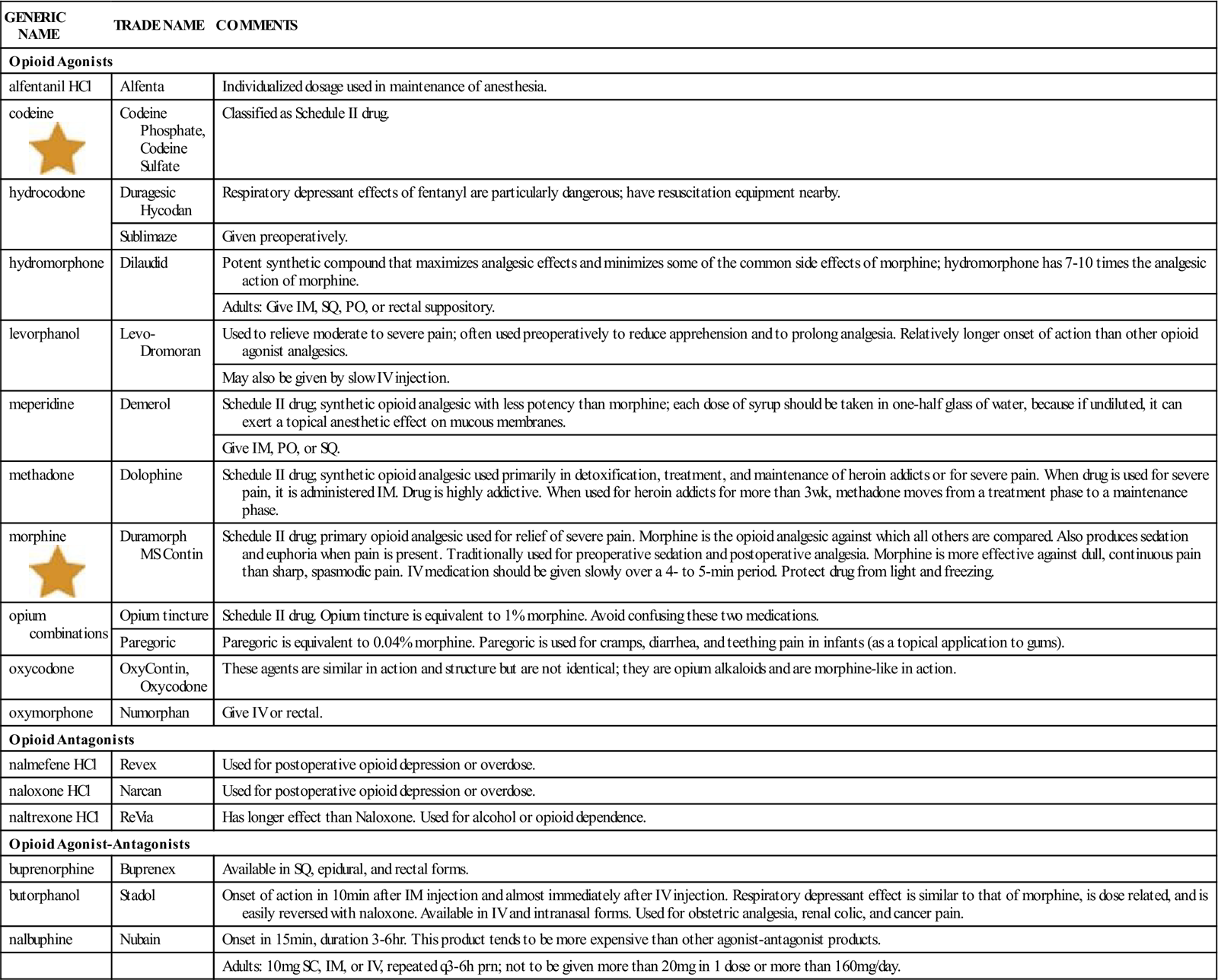

The specific information for the opioid agonist analgesics is listed in Table 17-3. A selection of the opioid analgesic combination products are also listed in Table 17-4.

![]() Table 17-3

Table 17-3

| GENERIC NAME | TRADE NAME | COMMENTS |

| Opioid Agonists | ||

| alfentanil HCl | Alfenta | Individualized dosage used in maintenance of anesthesia. |

| codeine |

Codeine Phosphate, Codeine Sulfate | Classified as Schedule II drug. |

| hydrocodone | Duragesic Hycodan |

Respiratory depressant effects of fentanyl are particularly dangerous; have resuscitation equipment nearby. |

| Sublimaze | Given preoperatively. | |

| hydromorphone | Dilaudid | Potent synthetic compound that maximizes analgesic effects and minimizes some of the common side effects of morphine; hydromorphone has 7-10 times the analgesic action of morphine. |

| Adults: Give IM, SQ, PO, or rectal suppository. | ||

| levorphanol | Levo-Dromoran | Used to relieve moderate to severe pain; often used preoperatively to reduce apprehension and to prolong analgesia. Relatively longer onset of action than other opioid agonist analgesics. |

| May also be given by slow IV injection. | ||

| meperidine | Demerol | Schedule II drug; synthetic opioid analgesic with less potency than morphine; each dose of syrup should be taken in one-half glass of water, because if undiluted, it can exert a topical anesthetic effect on mucous membranes. |

| Give IM, PO, or SQ. | ||

| methadone | Dolophine | Schedule II drug; synthetic opioid analgesic used primarily in detoxification, treatment, and maintenance of heroin addicts or for severe pain. When drug is used for severe pain, it is administered IM. Drug is highly addictive. When used for heroin addicts for more than 3 wk, methadone moves from a treatment phase to a maintenance phase. |

| morphine |

Duramorph MS Contin |

Schedule II drug; primary opioid analgesic used for relief of severe pain. Morphine is the opioid analgesic against which all others are compared. Also produces sedation and euphoria when pain is present. Traditionally used for preoperative sedation and postoperative analgesia. Morphine is more effective against dull, continuous pain than sharp, spasmodic pain. IV medication should be given slowly over a 4- to 5-min period. Protect drug from light and freezing. |

| opium combinations | Opium tincture | Schedule II drug. Opium tincture is equivalent to 1% morphine. Avoid confusing these two medications. |

| Paregoric | Paregoric is equivalent to 0.04% morphine. Paregoric is used for cramps, diarrhea, and teething pain in infants (as a topical application to gums). | |

| oxycodone | OxyContin, Oxycodone | These agents are similar in action and structure but are not identical; they are opium alkaloids and are morphine-like in action. |

| oxymorphone | Numorphan | Give IV or rectal. |

| Opioid Antagonists | ||

| nalmefene HCl | Revex | Used for postoperative opioid depression or overdose. |

| naloxone HCl | Narcan | Used for postoperative opioid depression or overdose. |

| naltrexone HCl | ReVia | Has longer effect than Naloxone. Used for alcohol or opioid dependence. |

| Opioid Agonist-Antagonists | ||

| buprenorphine | Buprenex | Available in SQ, epidural, and rectal forms. |

| butorphanol | Stadol | Onset of action in 10 min after IM injection and almost immediately after IV injection. Respiratory depressant effect is similar to that of morphine, is dose related, and is easily reversed with naloxone. Available in IV and intranasal forms. Used for obstetric analgesia, renal colic, and cancer pain. |

| nalbuphine | Nubain | Onset in 15 min, duration 3-6 hr. This product tends to be more expensive than other agonist-antagonist products. |

| Adults: 10 mg SC, IM, or IV, repeated q3-6h prn; not to be given more than 20 mg in 1 dose or more than 160 mg/day. | ||

IM, Intramuscular; IV, intravenous; PO, by mouth; prn, as needed; SQ, subcutaneous.![]() Indicates “Must-Know Drugs,” or the 35 drugs most prescribers use.

Indicates “Must-Know Drugs,” or the 35 drugs most prescribers use.

![]() Table 17-4

Table 17-4

Selected Opioid-Analgesic Combination Products

| TRADE NAME | CHEMICAL COMPONENTS |

| Acetaminophen with Codeine | Codeine, acetaminophen |

| ASA with Codeine Compound | Codeine, aspirin (ASA) |

| Empirin with Codeine | Codeine, aspirin |

| Fiorinal with Codeine | Codeine, aspirin, caffeine, butalbital |

| Percocet | Oxycodone, acetaminophen |

| Percodan | Oxycodone, aspirin |

| Phenaphen-650 with Codeine | Codeine, acetaminophen |

| Tylox | Oxycodone, acetaminophen |

| Vicodin, Lortab | Hydrocodone bitartrate, acetaminophen |

n Evaluation

Usually, oral opioid agonist analgesics begin to take effect in 15 to 30 minutes. The time needed for opioids injected into the tissue to take effect may vary depending on the route of administration. This is because of differences in the ability of these drugs to be metabolized, which causes differences in how fast the body can absorb them. Opioids given by mouth are much less effective than those given by injection because much of the medicine is destroyed by the stomach acid. However, oral opioid agonist analgesics produce pain relief for a longer time. Following institutional policies, intravenous (IV) opioids may be given in small doses by PCA by the patient or nurse through IV tubing.

The dose of the opioid agonist analgesic depends on the severity of the pain experienced by the patient, the patient’s response to the pain and the medication, and the nature of the illness. In the past, many patients had pain because the dose of medication was not high enough. In the last 10 years, higher doses have been recommended for treating patients with cancer or chronic pain. The new guidelines suggest much higher doses at more frequent intervals and for longer times than previous guidelines. The doses for such patients are much higher than preoperative doses or postoperative doses for acute pain.

The patient who receives any type of opioid analgesic should be checked at regular, frequent intervals. Because opioid agonist analgesics may slow the respiratory rate and decrease the cough and sigh reflexes, patients who have had surgery, especially those who have smoked for a long time, may develop areas where the lungs do not inflate well (atelectasis) or collect fluid and develop pneumonia.

In both the hospital or out patient office, the nurse has the chance to assess each patient’s behavior while taking the drug. For example, the patient may be unable to stop taking the drug, may make frequent requests for the drug, or may use more than one health care provider or office. These behaviors may be signs of dependence, abuse, or addiction.

Opioid agonist analgesics are metabolized by the liver, and any unused chemicals leave the body through the kidneys; 90% of most opioids are passed with the urine in first 24 hours.

n Patient and Family Teaching

Tell the patient and family the following:

Opioid Agonist-Antagonists

Overview

Opioid agonist-antagonists are strong drugs that act through the CNS, possibly at the limbic system. They act with other chemicals at specific nerve sites.

Action

Drugs in this category have different sites of action, but they usually act like morphine in producing analgesia, euphoria, and respiratory depression. Some drugs may compete with other opioids. Thus they may produce withdrawal symptoms in patients who are dependent on opioids, but they are also less likely to be abused than pure opioid agonists.

Uses

Opioid agonist-antagonists are used mostly for the relief of moderate to severe pain. They are also used in the injectable form for preoperative analgesia and for pregnant women during active labor. These drugs may be better than opioids for use in patients outside the hospital. Tramadol (Ultram) is an agonist-antagonist in common use in office practice that has a unique dual mechanism action as a mu-opioid receptor agonist and a weak inhibitor of norepinephrine and serotonin reuptake.

The specific information for opioid agonist analgesics is listed in Table 17-3.

Adverse Reactions

Adverse reactions to opioid agonist-antagonists include bradycardia, hypertension (high blood pressure) or hypotension, tachycardia (rapid heartbeat), changes in mood, blurred vision, confusion, dizziness, headache, weakness, nervousness, nystagmus (rhythmic movement of the eyes), syncope (light-headedness and fainting), tingling, tinnitus (ringing in the ears), tremor, unusual dreams, pruritus, rash, hardening of the soft tissue from swelling, stinging on injection, ulcers, anorexia, abdominal cramps, constipation, diarrhea, dry mouth, dyspepsia (stomach discomfort after eating), nausea, vomiting, low production of white blood cells, dyspnea (uncomfortable breathing), flushing, speech difficulty, and either the urge to urinate or difficulty urinating. Overdosage may produce sedation and respiratory depression.

Drug Interactions

Alcohol and drugs that slow the actions of the body (depressants) should be used with caution with opioids because of the risk for increased CNS depression.

Nursing Implications and Patient Teaching

Nursing Implications and Patient Teaching

n Assessment

Learn as much as possible about patients’ health history, including the presence of lung, liver, or kidney disease; pregnancy or breastfeeding; recent heart attack; or clues that they might have emotional problems or might have problems with drug dependency or drug misuse. These conditions may be contraindications or precautions to the use of opioid agonist-antagonist analgesics.

The individual’s subjective experience of the pain and his or her pain tolerance should be determined. A history of the pain, including when it started, where it is located, what it feels like, how bad it is, and things that make it worse or make it better should be obtained. The nurse may see that the patient has tensed muscles, shallow breathing, changes in blood pressure or pulse, sweating, changes in reaction of the pupils, or restlessness, crying, or moaning. Use a pain scale to classify pain before, during, and after giving pain medication.

n Diagnosis

Are there any other problems in addition to the medical diagnosis that will affect the patient’s response to these drugs? Is the patient frightened? Are there concerns about blood loss, ability to breathe, safety, and whether tissues are dry (hydration)? Any problems discovered should be reported to the registered nurse or physician.

n Planning

Opioid agonist-antagonists should be used with caution in patients who have emotional problems or in those who have a history of drug abuse. Because both physical and emotional dependence may occur, these drugs should be given to such patients only when they can be carefully watched and given only in limited amounts.

Opioid agonist-antagonists should not be given to patients with head injury, because the nurse will need to be able to monitor how the patient acts without the confusing effects of the medication. It has not been established whether it is safe to use these drugs in children or in pregnant women (other than during labor). Because these drugs tend to cause slowed breathing, they should be used very carefully in patients with breathing problems (especially asthma), obstructive breathing conditions, and cyanosis. Pain is an important finding that helps clinicians figure out what is wrong with the patient. For example, abdominal pain from appendicitis. These patients should not have pain medication until it is determined what is wrong with the patient.

Opioid agonist-antagonists may produce withdrawal symptoms in patients who have developed dependence. These products may also cause seizures, especially in patients with known seizure disorders.

Patients who take combination drug products may have adverse effects or develop problems due to any of the drugs used in the medications.

n Implementation

All of these opioid agonist-antagonists are available in injectable form, but only pentazocine (Talwin) is available in oral form. These medications should be given by intramuscular (IM) injection because subcutaneous injection may damage tissues.

When frequent injections are needed, give each dose in a different site to avoid damaging the tissues. (Refer to Figure 10-15, which shows a typical injection rotation plan.)

For acute pain, one to two tablets or capsules of opioids combined with other medications are given every 4 to 6 hours. Table 17-3 presents a review of opioid agonist-antagonist medications.

n Evaluation

Monitor the patient to determine whether relief from pain has been achieved and whether any adverse effects have developed as a result of the medicine. If the patient starts seeing things that are not there (hallucinations), or becomes confused or consciousness is reduced, the medication should be stopped.

Watch the patient’s behavior for signs for dependence. For example, the patient may be unable to stop taking the drug, may want the drug all the time, or may try to get the drug from multiple physicians or hospitals.

n Patient and Family Teaching

Nonopioid (Centrally Acting) Analgesics and Combination Analgesic Drugs

Overview

Nonopioid (centrally acting) analgesics are drugs that act at the level of the brain to control mild or moderate pain. Many times, small amounts of opioids are included, along with analgesics such as acetaminophen or aspirin, for treatment of minor acute pain.

Action and Uses

Nonopioid (centrally acting) analgesics are a small group of miscellaneous drugs. Many of these are used primarily to relieve mild to moderate pain. (See Table 17-5 for a selected listed of these drugs.)

![]() Table 17-5

Table 17-5

Nonopioid Centrally Acting Analgesics

| GENERIC NAME | TRADE NAME | COMMENTS |

| clonidine | Duraclon | Give 30 mcg/hr for continuous epidural infusion. |

| tramadol | Ultram | Give PO. |

Many of the nonopioid-analgesics are combination drugs that include other chemicals that also work on the pain centers of the CNS. These drugs may contain acetaminophen, aspirin, and caffeine, combined with opioids such as codeine, oxycodone, or hydrocodone. Some combination agents also contain a form of barbiturate (butalbital), which is added for its sedative (calming) effects. Caffeine, a plant extract, has mild brain, lung, and heart stimulant effects, as well as some diuretic activity. It has no analgesic properties, but it is used to treat some types of headaches. Opioids and barbiturates are legally defined as controlled substances, so there are many rules about how they are prescribed.

Combination drugs are used for the relief of moderate to severe pain of an acute origin, such as postoperative or dental pain when a tooth is pulled. They are often ordered when the patient leaves a hospital or when the patient is not in a hospital. These drugs are addictive and should be used for only a brief time. Table 17-6 lists common nonopioid combination products used for analgesia.

![]() Table 17-6

Table 17-6

Selected Nonopioid Analgesic Combination Products

| TRADE NAME | CHEMICAL COMPONENTS |

| Anacin | Aspirin, caffeine |

| Bromo-Seltzer | Acetaminophen, sodium bicarbonate, citric acid |

| Equagesic | Aspirin, meprobamate |

| Excedrin | Aspirin, acetaminophen, caffeine |

| Fiorinal | Aspirin, caffeine, butalbital |

| Vanquish | Aspirin, acetaminophen, caffeine, antacids |

There are many different combination products. The dosages and formulations often change. Consult a drug formulary for the latest information.

Adverse Reactions

Adverse reactions to nonopioid analgesics include the same adverse effects found with the drugs that make up the combinations. Thus, each drug combination will have its own adverse effects profile. Many of these products are considered quite safe with mild symptoms that include nausea, vomiting, and increased risk of GI bleeding. High doses may be involved with agitation, anxiety, tinnitus, and kidney damage depending upon the products involved.

Drug Interactions

Nonopioid analgesics have CNS depressant effects that add to those of other depressants, including alcohol. Each product interacts with other drugs, although these products have fewer chemical interactions than opioids.

Nursing Implications and Patient Teaching

Nursing Implications and Patient Teaching

n Assessment

Learn as much as possible about the patient’s health history, including whether the patient has any respiratory or hepatic disease, or is pregnant or breastfeeding. In addition, look for clues that the patient has emotional problems or has had problems with drug dependency or drug misuse. These conditions may be contraindications or precautions to use of nonopioid analgesics.

Determine the patient’s feelings about the pain and its history, including when it started, where it is located, what it feels like and how severe it is, and things that make it worse or make it better. The nurse may also see that the patient has tensed muscles, changes in breathing, sweating, change in pupils, restlessness, crying, or moaning, as well as changes in blood pressure and pulse rate. How well the patient can accept pain should be determined. Use a pain scale to grade the intensity of the patient’s pain.

n Diagnosis

What other problems does the patient have that might interfere with the action of this medication? Are there concerns about moving around, sensory awareness, or level of alertness?

n Planning

Do not give nonopioid analgesics, including phenothiazines, to patients who are allergic to the products they contain. Always ask the patient about drug allergies before giving a medication.

n Implementation

These drugs are available in a variety of forms. Many of these products the patient will take by themselves at home.

n Evaluation

Check the patient regularly and frequently to determine the response to the drug. If the patient seems confused, look for symptoms of overdosage. Patients who have emotional problems, who have abused drugs in the past, or who may not take their medicine properly should not be given these medications.

Because of the risk of hepatotoxicity in former alcoholics using acetaminophen, watch for any sign of alcohol abuse.

n Patient and Family Teaching

Drugs for Anesthesia

When a part of the body or the total body can be made numb and unresponsive to pain, this is known as anesthesia. If the loss of sensation is only a very small part of the body, we call it local anesthesia. Dental procedures or minor surgery are examples. This type of anesthesia may be produced by topical application of a medication or by injecting the medication into the skin (infiltration). Regional anesthesia achieves loss of sensation in a larger area by deadening a nerve that would carry pain (nerve block), and injection of medicine into the spinal canal or epidural areas controls pain sensations in a particular area.

Local anesthetics interrupt pain and motor sensation by blocking the movement of sodium ions into neurons. The length of this activity is usually short but can be increased by adding other medications to the injection. The local anesthetics are classified by their chemical structures as either amides or esters. Amides are most commonly used because they have fewer side effects and a longer duration of action. Adverse effects to local anesthetics are uncommon but some people may be allergic to the drug or the preservatives that might be added to the medication. Sometimes patients with heart disease are particularly sensitive and have longer systemic effects, such as anxiety, restlessness, hypotension, or irregular heartbeats, caused by local anesthetics if they contain epinephrine (adrenaline); Common local anesthetics that might be used are listed in Table 17-7.

![]() Table 17-7

Table 17-7

Selected List of Local Anesthetics

| DRUG | COMMENTS |

| articaine (Septanest) | Very long duration. Good for nerve blocks. |

| benzocaine (Americaine, Solarcaine) | Topical OTC anesthesia used for sunburn and minor abrasions |

| bupivacaine (Marcaine) | Used in epidural anesthesia |

| dibucaine (Nupercaine) | Used in topical or spinal anesthesia. |

| etidocaine (Duranest) | Used in nerve blocks, procedures, and epidural and spinal anesthesia. |

| lidocaine (Xylocaine) | Most popular agent used for topical, procedures, nerve block, and epidural and spinal anesthesia. |

| mepivacaine (Carbocaine) | Used for nerve block and epidural anesthesia; intermediate duration |

| procaine (Novocain) | Short duration ester used in procedures, nerve blocks, and epidural and spinal anesthesia. |

| prilocaine (Citanest) | Used for procedures, nerve block, and epidurals; intermediate duration. |

| tetracaine (Pontocaine) | Ester used for long duration in topical and spinal anesthesia. |

General anesthesia is produced when the body is unconscious and unresponsive. Patients may be heavily sedated or conversely, may have received a paralytic agent so they cannot move or breathe and must be intubated. Patients not only do not feel pain, they cannot move, talk, or breathe by themselves. An anesthesiologist or nurse anesthetist must be there to help them breathe and to monitor their vital signs. General anesthesia is usually produced by giving IV medication or by having patients breathe a gas through their mouth and nose.

Many drugs may be given along with general anesthesia for different purposes. These include cholinergic agents to dry up respiratory secretions, opioids to help control pain, neuromuscular blocking agents to paralyze the muscles so the respiratory tube may be inserted and to prevent movement and intestinal protrusion during abdominal surgery. Drug combinations help the patient go quickly to sleep and progress to very deep relaxation so that surgical procedure is possible. The anesthesia provider makes sure the patient does not become too deeply anesthetized and decreases risk to the patient. Nitrous oxide is a gas used in obstetrics or dentistry or for short medical procedures. It may also be used with other more potent inhaled gases. Other anesthetics involve use of volatile liquids that are converted to gases for the induction (beginning) and maintenance of general anesthesia. Halothane (Fluothane) is the best-known volatile liquid, although it is not used as much now because newer products are safer; desflurane, enflurane, isoflurane, methoxyflurane, and sevoflurane are others that might be used. Methoxyflurane is often used in labor because it is the least likely to suppress uterine contractions.

Many drugs may be given prior to gas anesthesia to help relax the patient and reduce pain. Some of these preoperative drugs are those mentioned earlier in this chapter. Other IV drugs are given at the same time as inhaled anesthetics so that the dose of the inhaled drug can be reduced. This helps reduce the possibility of serious side effects. These IV drugs used as anesthetics include benzodiazepines, barbiturates, and opioids. Table 17-8 briefly identifies other IV drugs that might be used for anesthesia; however, more detailed information is provided in Chapter 16 and earlier in this chapter.

![]() Table 17-8

Table 17-8

Selected Other Drugs Used with Anesthetics

| INTRAVENOUS ANESTHETIC AGENTS | SELECTED DRUGS |

| Barbiturate and barbiturate-like agents | Etomidate, methohexital sodium, propofol, thiopental sodium |

| Benzodiazepines | diazepam, lorazepam, midazolam HCl |

| Opioids | alfentanil HCl, fentanyl, remifentanil, sufentanil |

| Others | ketamine |

| ADJUNCTS TO ANESTHESIA | SELECTED DRUGS |

| Barbiturates and barbiturate-like agents | amobarbital, butabarbital sodium, pentobarbital, secobarbital |

| Cholinergic agent | bethanechol |

| Dopamine blockers | droperidol, promethazine |

| Neuromuscular blockers | succinylcholine |

| Opioids | alfentanil, fentanyl, remifentanil, sufentanil |

What do licensed practical and vocational nurses (LPNs/LVNs) need to know about anesthesia? LPNs/LVNs may be asked to find medication for physicians to use to inject and produce local or regional anesthesia. They may occasionally give IM or prepare IV preoperative medications. But primarily LPNs/LVNs may hear the surgeons or anesthesiologists discussing general anesthesia or read about other IV medications that were given during surgery.

The role of the nurse for a patient going to surgery is primarily to monitor the patient and try to calm him or her. Patients are often frightened when going to surgery. If the patient has a history of fainting (hypotensive episode) when IV lines are started or if he or she is having an elective procedure for which anesthesia will be required, the anesthesiologist should know this so he or she will be able to watch for it. What previous nursing research has shown is that if patients are given good information about the procedure or surgery—where they will go, who will be with them during surgery, how long surgery will take, and how long they will be in the recovery room—that the incidence of nausea, vomiting, anxiety and pain are reduced.