CASE 17 Extensive Coronary Dissection

Cardiac catheterization

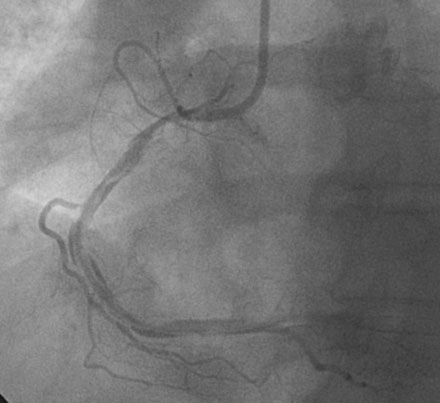

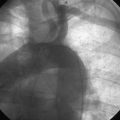

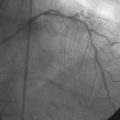

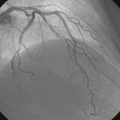

Cardiac catheterization revealed preserved left ventricular systolic function and multivessel coronary disease, with severe discrete stenoses of the proximal right coronary artery and left anterior descending artery and an angiographically normal circumflex artery (Figures 17-1, 17-2 and Videos 17-1, 17-2). The attending physician discussed revascularization options, and the patient chose percutaneous coronary intervention of both the right coronary and left anterior descending coronary arteries with drug-eluting stents instead of bypass surgery. She returned to the cardiac catheterization laboratory the next morning following a dose of 300 mg of clopidogrel taken the night before. The operator began with the left anterior descending artery. This was successfully treated with a 2.5 mm diameter by 18 mm long, drug-eluting stent (zotarolimus), with an excellent angiographic result (Figure 17-3). The operator engaged a 6 French right Judkins 4.0 guide catheter in the right coronary artery and easily crossed the stenosis with a floppy-tipped guidewire and predilated the lesion to 10 atmospheres with a 2.5 mm diameter by 15 mm long compliant balloon. The operator then attempted, but failed to pass, a 2.5 mm diameter by 24 mm long drug-eluting stent (zotarolimus) across the lesion. The stent met significant resistance at the site of a bend in the proximal right coronary artery (see Figure 17-1, arrow), and the attempt caused the guide to inadvertently disengage, resulting in loss of guidewire access to the distal right coronary artery. Angiography following reengagement of the guide catheter showed no obvious dissection but a persistent residual stenosis at the site of the balloon-dilated lesion (Video 17-3).

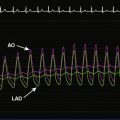

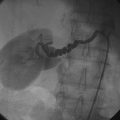

At this point, the operator chose an extra-support guidewire to facilitate stent placement (Mailman, Boston Scientific). Although the wire advanced with ease to a distal location in the posterolateral branch of the artery, the patient soon complained of severe chest pain associated with ST-segment elevation on the monitored leads. Fearing abrupt vessel closure, the operator repeated right coronary angiography, and noted an extensive spiral dissection along the entire course of the right coronary artery with closure of the posterolateral branch (Figure 17-4 and Video 17-4). The operator removed the extra-support wire, replacing it with a floppy wire, and successfully positioned this wire in the posterior descending artery (Video 17-5). Unable to pass short bare-metal stents beyond the proximal lesion, the operator consulted surgery for consideration of emergency bypass surgery.

Discussion

In the present era, the need to perform emergency coronary bypass surgery to treat a complication from percutaneous coronary intervention has become very rare.1 Currently, most emergency bypass operations occur when a dissection in a major artery cannot be stented or when a coronary perforation cannot be controlled by percutaneous means. Unfortunately, emergency bypass surgery in the setting of a failed percutaneous coronary intervention is associated with a high rate of in-hospital death, myocardial infarction, and stroke. Thus, in the event of a large, untreatable dissection, the risk-benefit ratio of surgery must be carefully weighed against the risk of leaving the artery closed and treating the resulting infarction medically. In the present case, the involved physicians and surgeons struggled with the decision to salvage the artery with emergency coronary bypass surgery. Although her continued chest pain and ST-segment elevation suggested the need for surgical treatment, the procedure likely offered only a modest benefit given the size of the right coronary artery. The decision to operate is easier when the affected artery supplies a larger vascular territory. In addition, the involved physicians feared stent thrombosis in the freshly placed stent in the left anterior descending artery induced by the stress of surgery.