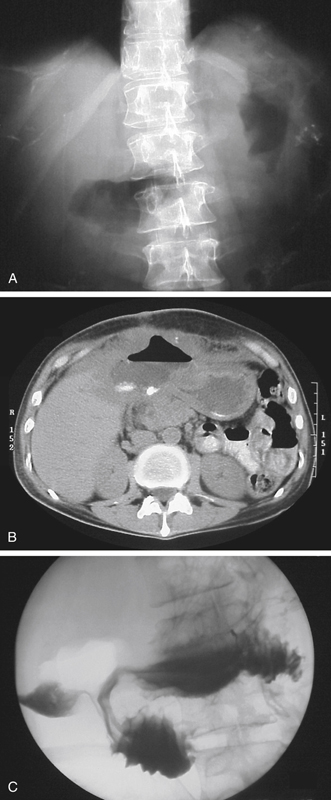

CASE 163

History: A 55-year-old man presents with abdominal pain.

1. What should be included in the differential diagnosis of the imaging finding shown in Figures A and B? (Choose all that apply.)

2. Which of the following is a mucosal defect replacing two thirds of the duodenal bulb?

3. Where do perforating ulcers most commonly occur?

4. Which of the following duodenal neoplasms can be specifically diagnosed with CT?

ANSWERS

CASE 163

Giant Duodenal Ulcer

1. A, C, D, and E

2. A

3. C

4. A

References

Kirsh IE, Brendel T. The importance of giant duodenal ulcer. Radiology. 1968;91(1):14–19.

Cross-Reference

Gastrointestinal Imaging: THE REQUISITES, 3rd ed, p 99.

Comment

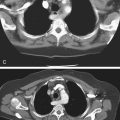

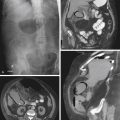

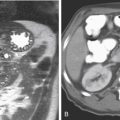

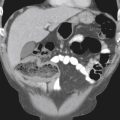

This patient has a giant duodenal ulcer (see figures). The luminal (Gastrografin) study shows retained contrast material within what appears to be a duodenal configuration (see figures). However, no fold pattern is detected. Postbulbar narrowing can also be seen frequently in giant duodenal ulcer disease. The most important complications are bleeding and perforation. The CT image shows large amounts of gas and oral contrast agent in a dependent position within the cavity of the giant ulcer (see figures). CT is very useful to diagnose perforation complicating the ulcer. CT may show 1 to 2 mL of free intraperitoneal air. Studies have indicated that upright or decubitus radiographs also may show similarly tiny amounts of free intraperitoneal air (see figures).

In practice, CT has proved more sensitive than other modalities in showing small amounts of free intraperitoneal air. Also, patients are often too sick to obtain adequate positional views for abdominal studies, and the demonstration of free intraperitoneal air on CT is not dependent on upright positioning. Although the indirect signs of pneumoperitoneum may be seen on conventional images in patients who are too ill to stand, CT is very sensitive for the detection of free air regardless of the patient position. A diagnosis of free intraperitoneal air may be easy to make, but the exact site of perforation may not be so easy to determine. Sometimes the site of perforation is identified at the time of surgery.

Plain radiographs of the abdomen reveal only the presence of free intraperitoneal air, which is a nonspecific finding. However, with the increased use of CT in the emergency setting, the detection of contrast material leaking into the peritoneal cavity and the presence of free intraperitoneal air has become possible. In the right clinical setting, it is unnecessary to perform further studies, and surgery should be performed promptly.