CHAPTER 160

Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

Sallaya Chinratanalab, MD; John Sergent, MD

Definition

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a multisystem autoimmune disease that is associated with autoantibody production and complement-fixing immune complex deposition. The immune system attack triggers an inflammatory process, resulting in tissue damage. SLE is the prototype of an autoimmune disease that can cause a wide spectrum of clinical presentations and is characterized by remissions and exacerbation. Periods of active illness are sometimes called flares. The course of the disease is unpredictable but can sometimes be triggered by environmental factors, such as ultraviolet light and certain drugs. Although the cause of SLE is not yet fully elucidated, there are known to be a variety of genes that make individuals susceptible to the disease and to its flares. SLE can affect skin, joints, kidneys, lungs, heart, blood vessels, liver, and the nervous system. The disease occurs nine times more often in women than in men, especially in the childbearing years between the ages of 15 and 45 years. The disease can also be found in pediatric and geriatric populations. The prevalence in the general population is approximately 1 in every 2000 persons, but it varies according to race, ethnicity, and socioeconomic background.

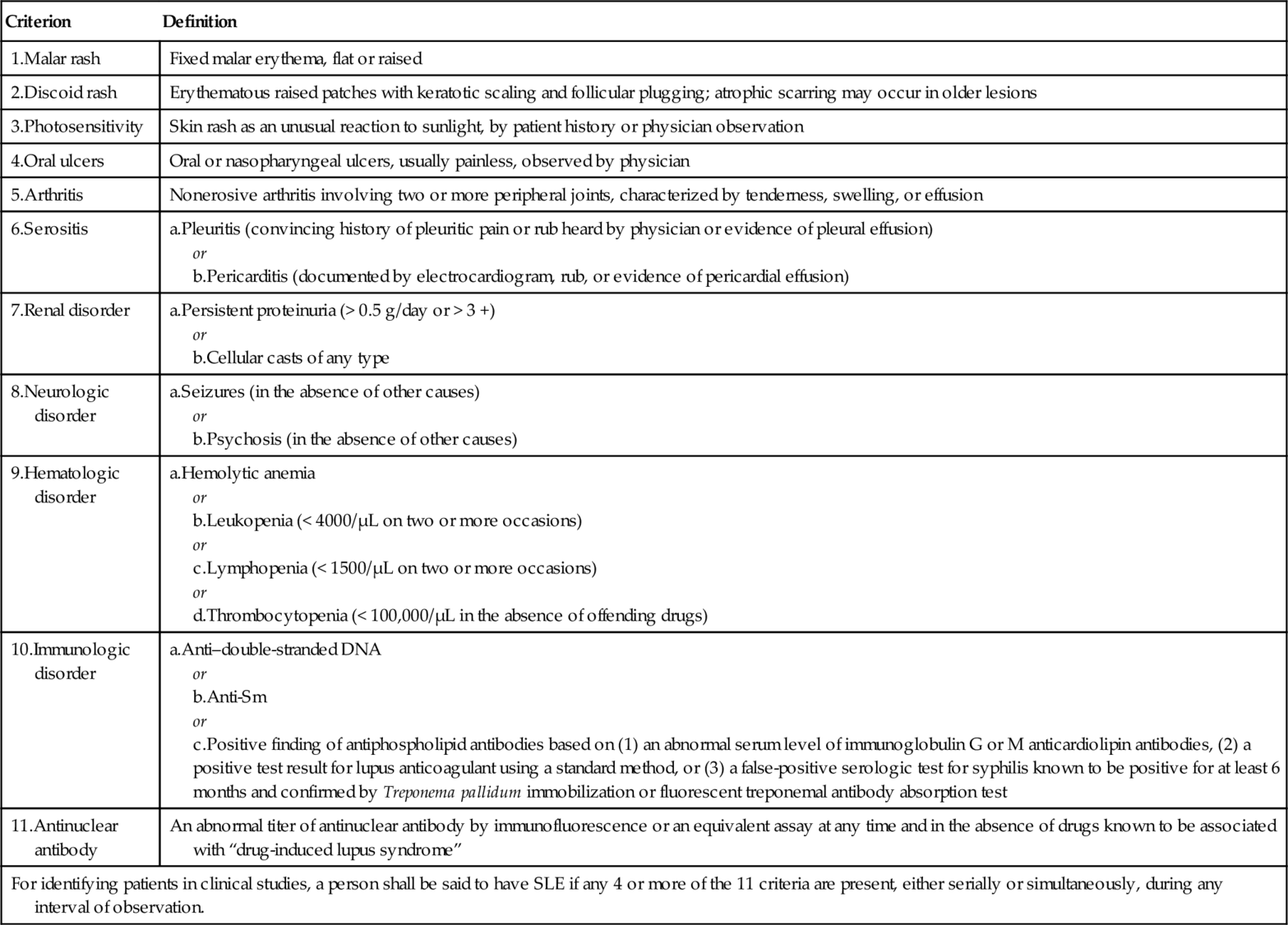

The American College of Rheumatology formulated a set of clinical and laboratory findings known as the classification criteria of SLE in 1985 and subsequently revised them in 1997 (Table 160.1). The classification criteria were designed for investigators recruiting SLE patients into clinical trials, but many clinicians also commonly use them in practice to establish a diagnosis in a given patient.

Symptoms

SLE can cause a variety of symptoms ranging from mild to severe. Patients can present with constitutional symptoms and organ-specific symptoms. Constitutional symptoms include fever, weight loss, and fatigue, which are typically present at some time during the course of the disease in most SLE patients. Mucocutaneous manifestations are important, as shown by the fact that they account for 4 of the 11 classification criteria (see Table 160.1). Skin lesions can be burning, tender, or itching. Rashes such as the classic malar (butterfly) rash and discoid lesions are characteristic. Patients may experience photosensitivity after a period of sun exposure. Photosensitivity is clinically defined as an abnormal response to ultraviolet light. These responses are manifested as exaggerated sunburn reactions and are often associated with systemic symptoms including fever, weakness, fatigue, and joint pain. Photosensitivity seems to correlate strongly with the presence of Ro/SSA antibodies [1]. Oral ulcerations are common and may be painless or asymptomatic. They are commonly on the hard palate and usually indicate active disease. The location and often asymptomatic nature of lupus-related oral ulcerations help differentiate them from non-lupus ulcerations, including aphthous stomatitis, lichen planus, herpes simplex, and drug-related lesions such as thrush due to corticosteroids and mucositis due to methotrexate. Nasal ulcers can also be found during disease activity and are often painful.

Patients may note thin hair, alopecia, or bald spots. Diffuse alopecia is nonspecific and can be caused by many systemic illnesses as well as by drugs such as cyclophosphamide and steroids. Focal bald spots, known as alopecia areata, are almost always due to autoimmune reactions and are characteristic of SLE. Painful red eyes from episcleritis, scleritis, or uveitis can be seen in SLE patients. Visual loss can occur in SLE patients with retinitis, vasculitis, optic neuritis, or thrombosis due to the antiphospholipid antibody syndrome. Some SLE patients experience sicca symptoms of dry eyes and dry mouth due to secondary Sjögren syndrome.

Patients may present with pleuritic chest pain related to serositis or pulmonary embolism. In addition, SLE patients have a very high incidence of premature atherosclerosis, and myocardial infarctions and strokes are not uncommon in young women with SLE. The authors have seen such events in a number of women in their late teens and 20s.

Epigastric pain in SLE patients can be due to nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, but the differential diagnosis must include pancreatitis, a life-threatening complication of SLE or of drugs used to treat it, such as azathioprine.

Patients presenting with dependent edema must be evaluated for lupus nephritis, which can cause the nephrotic syndrome. In the case of unilateral leg swelling, deep venous thrombosis needs to be ruled out. The hypercoagulable state in SLE patients is often associated with the antiphospholipid antibody syndrome. Antiphospholipid antibodies, including the lupus anticoagulant, are seen in approximately one fourth of SLE patients. Many remain asymptomatic, but the antibodies are associated with a number of clinical manifestations, including deep venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolism, arterial clots, recurrent spontaneous abortions, and strokes.

Articular symptoms are almost universal in SLE patients. Typical joint involvement in SLE affects the small joints of the hands as well as the wrists, feet, and knees. The joint symptoms are inflammatory in nature; therefore, they tend to be worse in the morning and are often accompanied by generalized stiffness. Patients generally experience significant joint pain out of proportion to objective physical findings. In patients who have received high doses of corticosteroids, avascular necrosis (osteonecrosis) needs to be in the differential diagnosis of severe joint pain, especially in the hips, knees, and shoulders. Raynaud phenomenon is an additional risk factor for this complication in SLE.

Raynaud phenomenon occurs in at least a third of SLE patients and may be the presenting manifestation. Raynaud phenomenon is caused by episodic vasospasm and ischemia of the extremities in response to cold or emotional stimuli. Typical color change is triphasic from white to blue to red, but many patients do not go through all three phases. Instead, they may just have periods of blanching followed by a return to normal color. In severe cases, digital ulcers may occur and can lead to shortening of the distal phalanx.

Neurologic symptoms, including headaches, numbness, tingling, and weakness, can vary from mild to severe. Strokes are found at an increased incidence in SLE because of both the accelerated atherosclerosis mentioned before and the hypercoagulable state due to associated antiphospholipid antibodies. SLE can also affect the spinal cord with rapidly progressive transverse myelitis, a consideration in any patient with lower extremity neurologic symptoms plus bladder or bowel incontinence.

Proximal muscle weakness involving the upper arms and thighs can be seen in SLE patients as a result of concomitant inflammatory muscle disease. SLE patients are also at risk for steroid myopathy, which is typically much worse in the proximal lower extremities. Patients with myopathy generally present with significant muscle weakness rather than with muscle pain. They have difficulty in using their arms for over-the-shoulder tasks and difficulty in getting up from a chair or a low position as well as using stairs.

Physical Examination

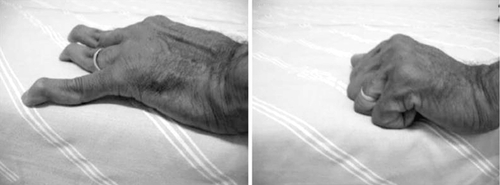

A thorough physical examination is important in evaluating SLE patients, given the nature of their multisystem involvement (Table 160.2). Articular manifestations can present as painful, nonerosive symmetric synovitis. Patients who have had repeated bouts of arthritis in their hands can also develop Jaccoud arthropathy, which is clinically characterized by reversible joint deformities including swan-neck changes, thumb subluxations, ulnar deviation, and boutonnière and hallux valgus deformities along with an absence of articular erosions on plain radiographs (Fig. 160.1). In general, its prevalence is around 5% to 10%.

Table 160.2

Organ Involvement in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

| Mucocutaneous | Facial rashes including malar or butterfly rash, discoid rash, alopecia, photosensitivity, oral ulcerations |

| Musculoskeletal | Joint pain with or without swelling, morning stiffness, Jaccoud arthropathy, muscle weakness, muscle aches and pain, osteonecrosis |

| Serosal | Pleuritis, pericarditis, peritonitis |

| Cardiovascular | Myocarditis, sterile endocarditis Premature atherosclerosis Raynaud phenomenon, digital ulcers |

| Pulmonary | Pulmonary hypertension, interstitial lung disease, diffuse alveolar hemorrhage, shrinking lung syndrome, pulmonary embolism |

| Hematologic | Leukopenia, anemia, thrombocytopenia |

| Renal | Nephritis, nephrotic syndrome |

| Neuropsychiatric | Headaches, seizures, stroke, peripheral neuropathy, cranial neuropathy, transverse myelitis, psychosis, cognitive dysfunction |

The skin is second only to the joints as the most frequently affected organ system, and skin disease is the second most common way that SLE initially is manifested clinically [2]. There are three major types of lupus-specific skin disease.

2. Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus. This is a distinct clinical subset of SLE. It is characterized by recurrent, erythematous, photosensitive, nonscarring skin lesions in a characteristic distribution involving the face, trunk, and arms and by mild systemic disease. Anti-Ro/SSA antibodies are found in 63% to 90% of patients with subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus [3]. The major anti-Ro/SSA response in subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus is directed against the native 60-kDa Ro protein [4]. Many drugs can induce SLE skin reactions, including photosensitizers such as spironolactone, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, calcium channel blockers, and hydrochlorothiazide. The skin lesions begin between 4 and 20 months after the initiation of drugs, and the lesions typically improve 6 to 12 weeks after the offending drug is withdrawn [5].

3. Chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus. The most common form is classic discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE). Clinical features of DLE are induration, scarring, pigment changes, follicular plugging, and hyperkeratosis. Involvement of hair follicles is a prominent clinical feature of DLE lesions. Typical DLE lesions occur most often on the face, scalp, ears, V-neck area of the neck, and extensor aspects of the arms. Scarring alopecia is often observed in patients with scalp involvement. Other forms of chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus include lupus profundus or panniculitis, mucosal DLE, and chilblain lupus or lupus pernio.

There are generally two common types of alopecia in SLE patients: irreversible scarring alopecia due to persistent DLE activity on the scalp; and the more widespread and often reversible nonscarring focal areas of alopecia that are often present during periods of disease activity. Hair in areas of alopecia is dry and coarse with increased fragility, making it break easily. This is often prominent over the frontal hairline.

Because of the nature of painless oral ulceration in SLE, the lesions are often found by a physician on a thorough physical examination, and patients may not recognize them. In patients with inflammatory eye disease such as uveitis or retinitis, a careful examination by an ophthalmologist is needed.

Parotid gland enlargement, several dental cavities, very dry buccal mucosa, or oral thrush can be found in patients with secondary Sjögren syndrome. Oral thrush can also be found in patients who are treated with steroids.

Cardiac examination may reveal a pericardial rub or distant heart sounds in SLE patients with pericardial effusion from pericarditis. Heart murmurs due to noninfectious endocarditis can be detected in SLE patients. Split P2, loud P2, or right-sided heart heave may suggest pulmonary hypertension, a complication of SLE associated with a high mortality rate. Crackles can also be found in SLE patients from interstitial lung disease, which is treatable if it is detected early.

Splenomegaly is occasionally seen in SLE patients with or without overt hematologic complications of the disease. Focal neurologic deficits and altered mental status can be found in SLE patients with central nervous system involvement including central nervous system vasculitis or stroke from associated antiphospholipid antibody syndrome. The peripheral nervous system can also be involved in SLE patients, including peripheral stocking-glove neuropathies as well as mononeuritis due to vasculitis. In SLE patients with secondary Raynaud phenomenon, abnormal nail fold capillaries can be detected with the presentation of dilated, unorganized capillaries or dropout lesions. Digital ulcers may be evident, and they may be difficult to heal.

Functional Limitations

Because SLE can affect so many systems, disability is common, although it may be reversible once the disease is treated and in remission. However, there are many patients with a complicated course of illness resulting in joint deformity, muscle weakness, or deconditioning after prolonged illness. The functional limitations can be a major issue for these patients even if their acute disease is under control.

All forms of cutaneous lupus have a significant socioeconomic impact within the United States. It has been suggested that cutaneous lupus is the third most common cause of industrial disability from dermatologic disease, with 45% of cutaneous lupus patients experiencing some degree of vocational handicap [6].

Lupus is associated with the gradual development of cognitive dysfunction in a minority of patients. The presence of antiphospholipid antibody, hypertension, and stroke are key variables associated with cognitive impairment [7].

Fatigue is one of the most common complaints and can be debilitating. The cause of fatigue is most likely multifactorial. Many potential causes include cytokines associated with active inflammation, deconditioning from prolonged illness, sleep disturbances, sedentary lifestyle, anemia, hypothyroidism, depression, stress, and medications such as steroids and beta blockers. Fatigue symptoms from SLE may respond to steroids or antimalarial treatment in some cases. Fatigue does not always correlate with other evidence of disease activity. There is a strong association between fatigue and decreased exercise tolerance. In one study of women with SLE, the oxygen consumption kinetics was prolonged and the prolongation was accompanied by an increase in oxygen deficit. This may explain the performance fatigability in this group of patients [8].

Diagnostic Studies

The classification criteria (see Table 160.1) can be a useful guide in making the diagnosis. The diagnosis of SLE is made by the American College of Rheumatology criteria if four or more of the manifestations are present, either serially or simultaneously, during any interval of observation.

Specific laboratory findings include antinuclear antibodies (ANA), antiphospholipid antibodies, and complement levels (Table 160.3). The most characteristic laboratory finding in SLE is the presence of ANA, and a negative ANA titer makes a diagnosis of lupus extremely unlikely. Titers are typically 1:160 or higher. Whereas the ANA titer is very sensitive, it is not very specific; the false-positive rate in healthy controls varies from approximately 30% with ANA titers of 1:40 (high sensitivity, low specificity) to as little as 3% with ANA titers of 1:320 (low sensitivity, high specificity) [9]. On the other hand, anti–double-stranded DNA and anti-Smith antibodies are highly specific for SLE. Anti-Ro/SSA and anti-RNP antibodies can also be found in SLE patients. Complement levels, usually C3 and C4, tend to fall during periods of active disease, especially if there is renal involvement. If patients have venous or arterial thrombosis or recurrent second-trimester spontaneous abortions, tests for the lupus anticoagulant should be performed.

Nonspecific laboratory findings include leukopenia, anemia, and thrombocytopenia, which are present in many patients during periods of active disease. Anemia can often be due to chronic disease or iron deficiency. Less commonly, it can be Coombs-positive hemolytic anemia. Proteinuria and hematuria with an active urinary sediment including cellular or granular casts are typical in SLE patients with nephritis. Kidney function can be compromised, as evidenced by elevated creatinine concentration and abnormal electrolyte levels. Creatine kinase concentration can be elevated in SLE patients with muscle involvement. Inflammatory markers, including erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein level, are usually elevated in SLE patients with active disease.

Imaging testing is generally obtained in SLE patients with signs or symptoms concerning for organ-specific manifestations. Plain radiographs of involved joints may show evidence suggestive of inflammatory arthritis, such as periarticular osteopenia. Renal ultrasonography is useful to assess kidney size in patients with renal insufficiency, and magnetic resonance angiography is used to assess renal vein thrombosis in patients with the nephrotic syndrome. Chest radiography may be helpful in SLE patients with cough, chest pain, or shortness of breath as lupus can cause both interstitial and pleural disease. Echocardiography is obtained in cases of suspected pericardial involvement or cardiac disease as well as to assess pulmonary artery pressure. Computed tomography of the chest is useful in SLE patients with interstitial lung disease, and a computed tomography scan of the abdomen may be considered in the evaluation of abdominal pain, especially when pancreatitis is suspected. Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain or spinal cord can give evidence that suggests a cause of focal neurologic deficits or cognitive dysfunction in SLE patients. In vasculitis, angiography may be valuable. When osteonecrosis is suspected, magnetic resonance imaging of joints is helpful. Musculoskeletal ultrasonography has been reported as a useful tool for assessment and defining of complications of joint and tendon in SLE patients [10].

In some cases, in addition to clinical and laboratory findings, the diagnosis of SLE is made by surgical pathology, such as skin or kidney biopsy showing characteristics strongly suggestive of SLE. Interface dermatitis with immune complexes at the dermal-epidermal junction is characteristic of lupus skin biopsy specimens. Immunofluorescent staining of kidney biopsy specimens from SLE patients commonly reveals “full-house staining” of immunoglobulin G, immunoglobulin M, immunoglobulin A, C3, and C1q.

Treatment

Treatment of SLE must be personalized for each patient by the extent of organ involvement. The purpose of treatment focuses on inducing remission, maintaining normal function, and preventing damage. Corticosteroid therapy is used in SLE at various dosages according to the severity of the disease. With serious organ involvement, such as kidney, lung, or central nervous system disease, cyclophosphamide therapy is commonly given along with corticosteroids. Other agents, such as azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil, leflunomide, rituximab, abatacept, intravenous immune globulin, and interferon alfa blockade, have been used in SLE.

Treatment of cutaneous lupus includes nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic approaches. Nonpharmacologic treatments are photoprotection from both ultraviolet A and B rays, smoking cessation, and avoidance of trauma to the skin (such as tattoos or tanning beds). Pharmacologic treatments include topical and systemic medications. Topical corticosteroids, intralesional corticosteroids, topical calcineurin inhibitors, and topical retinoids have been recommended in cutaneous lupus. The most common systemic medication used in cutaneous lupus is hydroxychloroquine. The combination of hydroxychloroquine and quinacrine or of chloroquine and quinacrine is an alternative when patients do not respond well to hydroxychloroquine alone. Other medications, such as methotrexate, oral retinoids, dapsone, mycophenolate mofetil, and thalidomide, have been used in cutaneous lupus.

The treatment of Jaccoud arthropathy is conservative. Medical treatment is recommended with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, low-dose corticosteroids, antimalarials, or methotrexate.

Hydroxychloroquine is effective for the amelioration of joint symptoms and for the prevention of clinical lupus relapse [11]. The dose is weight based at less than 6.5 mg/kg/day, which is generally 200 to 400 mg/day. The recommendations on eye screening for hydroxychloroquine or chloroquine retinopathy have been revised by the American Academy of Ophthalmology [12]. It is strongly recommended that all patients beginning hydroxychloroquine or chloroquine therapy have a baseline examination within the first year of starting the drug to document any complicating ocular conditions and to establish a record of the fundus appearance and functional status. Annual screening should be performed after 5 years of drug use in all patients. In patients with maculopathy or risk factors such as liver or renal disease or advanced age, annual screening should be performed from the initiation of therapy.

Belimumab is the first biologic agent approved for the treatment of SLE by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. It is the first drug approved in 55 years after hydroxychloroquine and corticosteroids were approved in 1955 and aspirin was approved in 1948. Belimumab is a fully humanized recombinant immunoglobulin G1λ monoclonal antibody that inhibits the binding of soluble B-lymphocyte stimulator to B cells and hence prevents the survival and differentiation of selected B-cell subsets. It is for the treatment of adult patients with active, autoantibody-positive SLE with a high degree of disease activity despite receiving standard therapy. It is well tolerated and appears to be efficacious in the treatment of SLE, although it is not approved for treatment of lupus nephritis or neuropsychiatric lupus [13,14].

Rehabilitation

In lupus patients with fatigue, supervised graded exercise programs show an improvement in aerobic capacity, quality of life, and depression [15,16]. The beneficial effects disappeared on stopping of exercise.

In some early cases of avascular necrosis, reduced weight bearing, limitation of activities, or use of crutches can occasionally slow the damage and permit natural healing [17]. Range of motion exercises are helpful for maintaining joint function.

In SLE patients with pulmonary hypertension, interstitial lung disease, or cardiac disease, cardiopulmonary rehabilitation is important once the patients are clinically stable.

Procedures

In lupus patients with active synovitis, tendinitis, or bursitis, local corticosteroid injections are helpful and can sometimes be used in lieu of systemic corticosteroids.

Osteonecrosis or avascular necrosis of the hip is a progressive disease. The prevention of femoral head collapse is highly desirable in the young lupus patient. In early-stage disease, before femoral head collapse (Ficat and Arlet stages I to III), core decompression of the femoral head is currently the most widely used procedure to try to relieve intraosseous pressure in the femoral head and to restore blood supply (Table 160.4).

Table 160.4

Avascular Necrosis of Femoral Head Classification: Ficat and Arlet

| Stage 0: preclinical or preradiologic | Normal findings on a plain radiograph in an asymptomatic patient with a positive diagnosis in the contralateral hip The magnetic resonance image shows a double-line sign, consistent with a necrotic process. |

| Stage I: preradiologic | Normal findings on radiographs and abnormal findings on magnetic resonance imaging or bone scintigraphy |

| Stage II: reparative stage | |

| Stage IIA | Radiographic changes are demineralization, patchy sclerosis in the superolateral aspect of the femoral head, and small cysts within the femoral head |

| Stage IIB | A transition phase characterized by the presence of the crescent sign, seen as a linear subcortical lucency situated immediately beneath the subcortical bone, representing a fracture line |

| Stage III | Flattened or collapsed femoral head |

| Stage IV | Progressive degenerative joint disease with severe collapse and destruction of the femoral head, joint space narrowing, and osteophyte and subchondral cyst formation |

Surgery

Lupus patients are prone to spontaneous tendon ruptures, including the Achilles tendon, the patellar tendon, and the long tendons of the hands. Early surgical repair is usually the treatment of choice.

In severe avascular necrosis of hips, knees, or shoulders, arthroplasty is required. Studies of the natural history of the disease suggest that femoral head collapse occurs within 2 to 3 years of the first symptoms, and at that stage arthroplasty is the most reliable treatment option. The outcome of hip arthroplasty showed an overall survival probability of 94.6% at 5 years and of 81.8% at 9 years with minimal perioperative morbidity [18]. Besides standard total hip arthroplasty, bipolar hemiarthroplasty, limited femoral resurfacing, and metal-on-metal resurfacing are alternatives. Because of the incidence of gluteal and groin pain and migration, total hip arthroplasty is a better procedure than bipolar hemiarthroplasty for patients with Ficat stage III osteonecrosis of the femoral head [19].

Potential Disease Complications

Jaccoud Arthropathy

This arthropathy may compromise hand function and is also a risk factor for tendon rupture [20].

Increased Risk of Infection

Although SLE patients are often leukopenic, they typically can mobilize white blood cells normally, so that SLE patients not receiving immunosuppressive therapy do not have a significantly increased risk of infection. However, patients receiving corticosteroids and other immunosuppressives are at increased risk of opportunistic infections. In anticipation of the need for immunosuppression, SLE patients should receive appropriate immunizations including pneumococcal and influenza vaccines. Live vaccines, such as the herpes zoster vaccine, should not be given to patients receiving immunosuppressive agents.

Hypertension

Hypertension can be seen in SLE patients with lupus nephritis and should be treated aggressively, preferably to 130/80 mm Hg or lower.

Premature Atherosclerosis

It has been recognized that premature coronary artery disease is a major cause of illness and death in SLE patients. Coronary atherosclerosis is much more prevalent among patients with lupus than in the general population and cannot be predicted by the measurement of traditional risk factors or markers of disease activity [21]. Many factors influence this process, including dysfunctional immune regulation, inflammation, traditional risk factors, defective endothelial cell function, and vascular repair as well the therapeutic used to treat the underlying autoimmune disease. SLE-specific factors including disease activity, disease duration, damage, and proinflammatory high-density lipoprotein could also contribute to increased atherosclerotic risk [22].

Potential Treatment Complications

The potential side effects and toxicities of hydroxychloroquine are retinal toxicity, hyperpigmented skin lesions, myopathy with vacuolization on muscle biopsy, and cardiomyopathy (Table 160.5).

Table 160.5

Potential Treatment Complications

| Treatment | Complication |

| Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs | Dyspepsia, peptic ulcer, gastrointestinal bleeding, platelet dysfunction, renal insufficiency, hepatotoxicity, aseptic meningitis |

| Glucocorticoids | Cushingoid appearance, weight gain, fluid retention, acne, hypertension, diabetes, cataracts, glaucoma, avascular necrosis, osteoporosis, impaired wound healing, increased susceptibility to infection |

| Antimalarials | Retinopathy, abnormal skin pigmentation, neuromyopathy, cardiomyopathy |

| Cyclophosphamide | Myelosuppression, hemorrhagic cystitis, bladder cancer, infertility, alopecia |

| Azathioprine | Myelosuppression, hepatotoxicity, pancreatitis |

| Methotrexate | Myelosuppression, hepatotoxicity, mucositis, alopecia, pneumonitis |

| Mycophenolate mofetil | Myelosuppression, dyspepsia, diarrhea |