CHAPTER 16

Rotator Cuff Tendinopathy

Definition

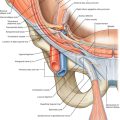

Rotator cuff tendinopathy is a common phenomenon affecting both athletes and nonathletes. The muscles that compose the rotator cuff—supraspinatus, infraspinatus, subscapularis, and teres minor—may become inflamed or impinged by the acromion, coracoacromial ligament, acromioclavicular joint, and coracoid process [1]. Fibroblastic hyperplasia (tendinosis) may play a role as well. The supraspinatus tendon is the most commonly involved.

Rotator cuff tendinopathy may result from a variety of factors. The tendon or its musculotendinous junction can be “squeezed” along its course from a relatively narrowed space [2]. Tendinosis can be a result of degeneration from the aging process or from underlying subtle instability of the humeral head [3,4].

In chronic rotator cuff tendinopathy, the muscles of the rotator cuff and surrounding scapulothoracic stabilizers may become weak by disuse. Under these conditions, the muscles can fatigue early, resulting in altered biomechanics. The humeral head moves excessively off the center of the glenoid, usually superiorly [5-8]. From this abnormal motion, impingement of the rotator cuff occurs, causing inflammation of the tendon. This is what many refer to as impingement syndrome; it particularly occurs during forward flexion when the anterior portion of the acromion impinges on the supraspinatus tendon.

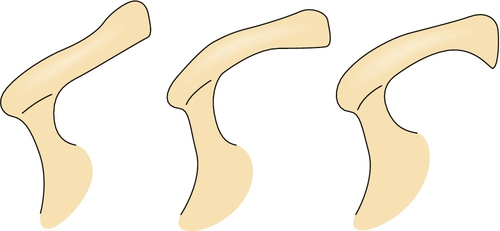

With the passage of time, modifications of the acromion occur, resulting in osteophyte formation or “hooking” of the acromion (Fig. 16.1) [1,9]. With repeated superior migration and acromial changes, degeneration of the musculotendinous junction can lead to tearing of the rotator cuff (see Chapter 17). With prolonged shoulder pain, adhesive capsulitis can develop from the lack of active motion (see Chapter 11).

Symptoms

Patients normally present with pain in the posterolateral shoulder region and, often, deltoid muscle pain, which is referred from the shoulder. The pain is described as dull and achy and often occurs at night. Complaints occur with activities above the shoulder level, usually when the arm is abducted more than 90 degrees. Pain is also noted in movements involving eccentric contractions, when sleeping on the affected side, and during overhead activities such as swimming and painting [10-14].

Physical Examination

The shoulder examination is approached systematically in every patient. It includes inspection, palpation, range of motion, muscle strength testing, and performance of special tests of the shoulder as clinically indicated.

The examination begins with observation of the patient during the history portion of the evaluation. The shoulder should be carefully inspected from the anterior, lateral, and posterior positions. Because shoulder pain is usually unilateral, comparison with the contralateral shoulder is often useful. Atrophy of the supraspinatus and infraspinatus muscles can be seen in massive rotator cuff tears as well as in entrapments of the suprascapular nerve. Scapular winging is rare in rotator cuff injuries; however, abnormalities of scapulothoracic motion are often present and should be addressed as part of the treatment plan.

Tenderness is often localized to the greater tuberosity, subacromial bursa, or long head of the biceps.

Total active and passive range of motion in all planes and scapulohumeral rhythm should be evaluated. Maximal total elevation occurs in the plane of the scapula, which lies approximately 30 degrees forward of the coronal plane. Patients with rotator cuff tears tend to have altered scapulothoracic motion during active shoulder elevation. Decreased active elevation with normal passive range of motion is usually seen in rotator cuff tears secondary to pain and weakness. When both active and passive range of motion is similarly decreased, this usually suggests the onset of adhesive capsulitis. Glenohumeral internal rotation is assessed most accurately by abduction of the shoulder to 90 degrees and manual fixation of the scapula. From this point, the elbow is flexed to 90 degrees and the humerus is internally rotated. The impingement syndrome associated with rotator cuff injuries tends to cause pain with elevation between 60 and 120 degrees (painful arc), when the rotator cuff tendons are compressed against the anterior acromion and coracoacromial ligament [5,6,15].

Muscle strength testing should be done isolating the relevant individual muscles. The anterior cuff (subscapularis) can be assessed by the lift-off test (see Chapter 14, Fig. 14.1), which is performed with the arm internally rotated behind the back. Lifting of the hand away from the back against resistance tests the strength of the subscapularis muscle. The posterior cuff (infraspinatus and teres minor) can be tested with the arm at the side and the elbow flexed to 90 degrees. Significant weakness in external rotation will be seen in large tears of the rotator cuff. The supraspinatus muscle is specifically tested by abduction of the patient’s arm to 90 degrees, horizontal adduction to 20 to 30 degrees, and internal rotation of the arm to the thumbs down position. Testing of the scapula rotators, the trapezius, and the serratus anterior is also important. The serratus anterior can be tested by having the patient lean against a wall; winging of the scapula as the patient pushes against the wall indicates weakness [15,16].

Drop Arm Test

The clinician abducts the patient’s shoulder to 90 degrees and then asks the patient to slowly lower the arm to the side in the same arc of movement. The test result is positive if the patient is unable to return the arm to the side slowly or has severe pain when attempting to do so. A positive result indicates a tear of the rotator cuff [17].

Impingement Sign

The shoulder is forcibly forward flexed with the humerus internally rotated, causing a jamming of the greater tuberosity against the anterior inferior surface of the acromion. Pain with this maneuver reflects a positive test result and indicates an overuse injury to the supraspinatus muscle and possibly to the biceps tendon (see Chapter 14, Fig. 14.2) [18].

Apprehension Test

The arm is abducted 90 degrees and then fully externally rotated while an anteriorly directed force is placed on the posterior humeral head from behind. The patient will become apprehensive and resist further motion if chronic anterior instability is present (see Chapter 14, Fig. 14.4) [1].

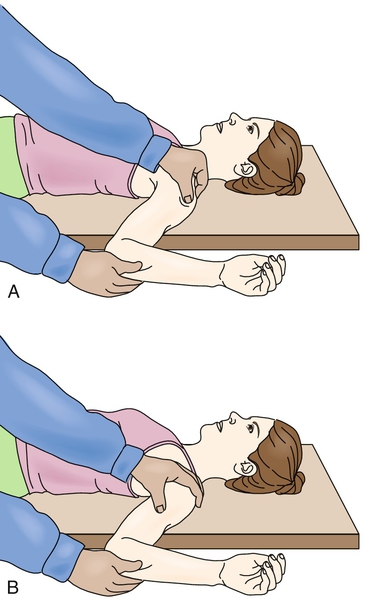

Relocation Test

Perform the apprehension test with the patient supine and the shoulder at the edge of the table (Fig. 16.2). A posteriorly directed force on the proximal humerus will cause resolution of the patient’s symptoms of apprehension, which is another indicator of anterior instability (see Chapter 14, Fig. 14.3) [1].

Functional Limitations

Patients with rotator cuff tendinopathy complain of limitations in the performance of overhead activities, such as throwing a baseball and painting a ceiling, particularly above 90 degrees of abduction [19-21]. Pain may also occur with internal and external rotation and may affect daily self-care activities. Women typically have difficulty hooking the bra in back. Work activities, such as filing, hammering overhead, and lifting, can be affected [22,23]. The patient can be awoken by pain in the shoulder, which impairs sleep [12].

Diagnostic Studies

In the event of trauma to the shoulder and complaints consistent with rotator cuff tendinopathy, the clinician should obtain radiographs to avoid missing an occult fracture. The anteroposterior view with internal and external rotation is sufficient for screening. If dislocation is suspected, further views should be obtained, including West Point axillary, true anteroposterior, and Y views.

Magnetic resonance imaging is the study of choice when a patient is not progressing with conservative management or to rule out an alternative pathologic process (e.g., rotator cuff tear). In tendinopathy, magnetic resonance imaging will demonstrate an increased T2-weighted signal within the substance of the tendon [22]. Diagnostic arthroscopy is used in some cases but is generally not necessary.

Electrodiagnostic studies can be ordered to exclude alternative diagnoses as well (e.g., cervical radiculopathy) [15,24].

Subacromial anesthetic injections (see Chapter 14, Figs. 14.5 and 14.6) have been discussed as diagnostic tools to assist in the confirmation of rotator cuff tendinopathy. This procedure is not as important for diagnosis of tendinopathy as it is for ruling out a tear. If the patient cannot provide good effort to abduction during the physical examination, the clinician can inject the anesthetic into the subacromial space. After the injection, if there is significant reduction in the pain level and the patient can provide adequate and nearly maximal abduction, tendinopathy is more likely than a rotator cuff tear [10,13,14].

Treatment

Initial

There are five basic phases of treatment (Table 16.1). These phases may overlap and can be progressed as rapidly as tolerated, but each should be performed to speed recovery and to prevent reinjury.

Initially, pain control and inflammation reduction are required to allow progression of healing and the initiation of an active rehabilitation program. This can be accomplished with a combination of relative rest from aggravating activities, icing (20 minutes three or four times a day), and electrical stimulation. Acetaminophen may help with pain control. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are avoided because of their negative effect on tendon healing. Having the patient sleep with a pillow between the trunk and arm will decrease the tension on the supraspinatus tendon and prevent compromise of blood flow in its watershed region.

Rehabilitation

Physical therapy may also help with pain management. Initially, gentle, passive, prolonged stretch may be needed. The use of ultrasound should be closely monitored to avoid heating of an inflamed tendon, which will worsen the situation. Postoperative rehabilitation will progress in a similar fashion once initial healing has occurred and at the discretion of the surgeon.

Restoration of Shoulder Range of Motion

After the pain has been managed, restoration of shoulder motion can be initiated. The focus of treatment in this early stage is on improvement of range, flexibility of the posterior capsule, postural biomechanics, and restoration of normal scapular motion. Codman pendulum exercises, wall walking, stick or towel exercises, and a physical therapy program are useful in attaining full pain-free range of motion. It is important to address any posterior capsular tightness because it can cause anterior and superior humeral head migration, resulting in impingement. A tight posterior capsule and the imbalance it causes force the humeral head anteriorly, producing shearing of the anterior labrum and causing additional injury [25]. Stretching of the posterior capsule is a difficult task. The horizontal adduction that is usually performed tends to stretch the scapular stabilizers, not the posterior capsule. However, stretching of the posterior capsule is possible if care is taken to fix and to stabilize the scapula, preventing stretching of the scapulothoracic stabilizers.

Postural biomechanics are important because with poor posture (e.g., excessive thoracic kyphosis and protracted shoulders), there is increased acromial space narrowing, resulting in greater risk for rotator cuff impingement [26,27]. Restoration of normal scapular motion is also essential because the scapula is the platform on which the glenohumeral joint rotates [28,29]. Thus, an unstable scapula can secondarily cause glenohumeral joint instability and resultant impingement. Scapular stabilization includes exercises such as wall pushups and biofeedback (visual and tactile) [30].

Strengthening

The third phase of treatment is muscle strengthening, which should be performed in a pain-free range of motion. Strengthening should begin with the scapulothoracic stabilizers and the use of shoulder shrugs, rowing, and pushups, which will isolate these muscles and help return smooth motion, allowing normal rhythm between the scapula and the glenohumeral joint. This will also provide a firm base of support on which the arm can move. Attention is then turned to strengthening of the rotator cuff muscles. Positioning of the arm at 45 and 90 degrees of abduction for exercises prevents the “wringing out” phenomenon that hyperadduction can cause by stressing the tenuous blood supply to the tendon of the exercising muscle. The thumbs down position with the arm in more than 90 degrees of abduction and internal rotation should also be avoided to minimize subacromial impingement. After the scapular stabilizers and rotator cuff muscles are rehabilitated, the prime movers are addressed to prevent further injury and to facilitate return to prior function.

There are many ways to strengthen muscles. The rehabilitation program should start with static exercises and co-contractions, progress to concentric exercises, and be completed with eccentric exercises. A therapy prescription should include the number of repetitions, the number of sets, and the intensity at which the specific exercise should be performed. When strength is restored, a maintenance program should be continued for fitness and prevention of reinjury. Local muscle endurance should also be trained.

Proprioception

The fourth phase is proprioceptive training. This is important to retrain the neurologic control of the strengthened muscles, providing improved dynamic interaction and coupled execution of tasks for harmonious movement of the shoulder and arm [31,32]. Tasks should begin with closed kinetic chain exercises (e.g., exercises done with the hand in contact with a fixed object like a wall) to provide joint stabilizing forces [33,34]. As the muscles are reeducated, exercises can progress to open chain activities, such as dumbbell exercises, that may be used in specific sports or tasks. In addition, proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation is designed to stimulate muscle-tendon stretch receptors for reeducation [35].

Task or Sport Specific

The last phase of rehabilitation is to return to task- or sport-specific activities [36,37]. This is an advanced form of training for the muscles to relearn prior activities. This is important and should be supervised so the task is performed correctly and the possibility of reinjury or injury in another part of the kinetic chain from improper technique is eliminated [38]. The rehabilitation begins at a cognitive level but must be repeated so that it transitions to unconscious motor programming [11].

Procedures

A subacromial injection of anesthetic can be beneficial in differentiating a rotator cuff tear from tendinopathy. Patients with pain that limits the validity of their strength testing may be able to provide almost full resistance to abduction and external rotation after the injection, suggesting rotator cuff tendinopathy. On the other hand, if there is continued weakness, one must consider a rotator cuff tear.

Many clinicians include a corticosteroid with the anesthetic to avoid the need for a second injection. This procedure can be both diagnostic and therapeutic. If one makes the diagnosis of rotator cuff tendinopathy, the corticosteroid injection will decrease the inflammation and allow accelerated rehabilitation. Moreover, a percutaneous tenotomy can be performed under ultrasound guidance. The needle is localized and placed in and out of the tendon to create small perforations within the damaged tendon. This stimulates the healing response through the inflammatory cascade, enhancing tendon repair.

Refer to the injection procedure in Chapter 14.

Surgery

Surgery should be considered if the patient fails to improve with a progressive nonoperative therapy program of 3 to 6 months. Surgical procedures may include subacromial decompression arthroscopically or, less commonly, open. At that time, the surgeon may débride the tendon and explore for other pathologic changes [14,39,40].

Potential Disease Complications

The greatest risk in not treating rotator cuff tendinopathy is rupture or tear of a tendon or the development of a labral tear. As previously discussed, with prolonged impairment in motion and strength and subtle instability, hooking of the acromion can develop. Adhesive capsulitis may develop with chronic pain and decreased shoulder movement as well [18,41-44].

Potential Treatment Complications

There are minimal possible complications from nonoperative treatment of rotator cuff tendinopathy. Because nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are used frequently, one must remain vigilant to their potential side effects (e.g., gastritis, ulcers, renal impairment, bronchospasm). Injections may cause rupture of the diseased tendon.