History: A 71-year-old woman presents with melena, nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain.

1. What is the minimal amount of free intraperitoneal gas visible on an upright chest film?

2. What is Rigler’s sign?

3. What imaging procedure is best for demonstrating free intraperitoneal gas?

A. Abdominal radiograph, erect

B. Abdominal radiograph, left decubitus

4. What is the usual amount of time for air that is introduced into the abdomen during surgery to be reabsorbed?

ANSWERS

CASE 16

Pneumoperitoneum

1. A

2. B

3. D

4. C

References

Miller RE, Nelson SW. The roentgenologic demonstration of tiny amounts of free intraperitoneal gas: experimental and clinical studies. Am J Roentgenol. 1971;112:574–585.

Cross-Reference

Gastrointestinal Imaging: THE REQUISITES, 3rd ed, p 332-335.

Comment

Intraperitoneal gas is often encountered in the abdominal cavity. The most common cause of the free gas is surgery or surgical laparoscopy. Air that is introduced into the abdomen during surgery usually takes 3 to 10 days to reabsorb. Under certain circumstances, this process can take several weeks. The more air introduced, the longer it takes to reabsorb. Thin patients take longer to reabsorb air. This finding might relate to the fact that obese patients usually have more omental fat, which decreases the amount of air that can be introduced. If the patient has postoperative ileus or peritonitis, the ability of the peritoneum to absorb the air is also reduced.

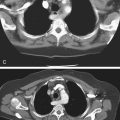

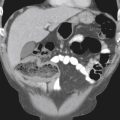

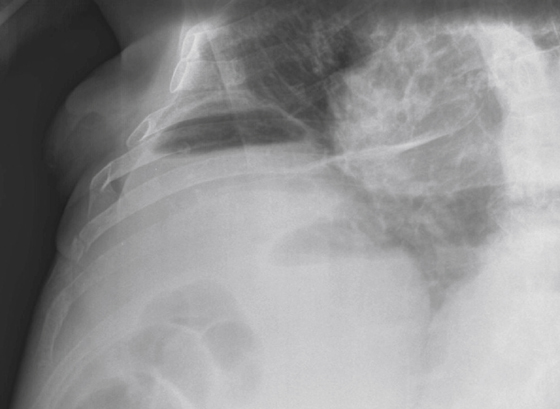

For many years, the upright chest film (see figures) and the left lateral decubitus view of the abdomen were considered the best for demonstrating even minute amounts (1 to 2 mL) of gas. However, CT has been shown to demonstrate free gas even when these views cannot. Multidetector computed tomography (MDCT) is now considered, by far, the best modality for demonstrating even the tiniest amounts of free gas.

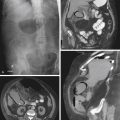

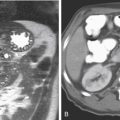

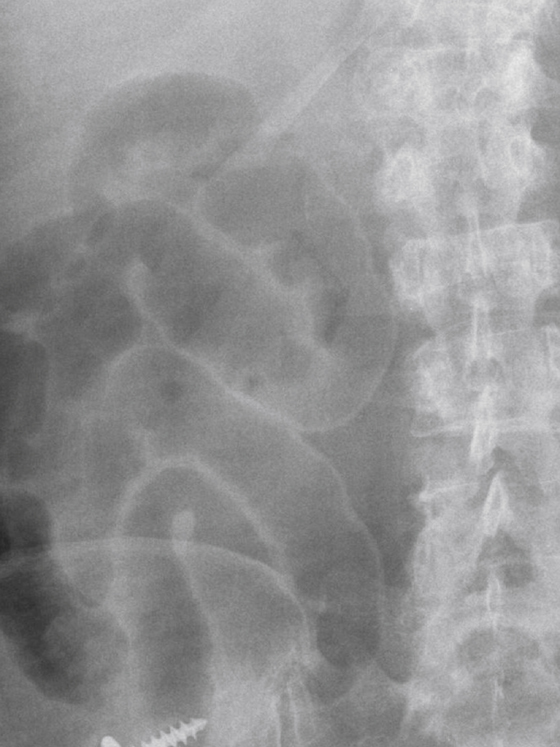

Several signs have been described regarding the appearance of free intraperitoneal gas on a conventional supine abdominal image. Often the patient is too sick for upright or decubitus views to be obtained, and the only view that can be obtained is a supine film (see figures). In this situation one or more of these signs may be seen.

Rigler’s sign refers to the ability to see both sides of the bowel wall because there is gas on both sides. What we routinely see on abdominal images when we see intestinal gas is actually a tissue-gas interface, specifically a mucosal-gas interface. The serosal side of the bowel cannot be seen without the presence of free gas in the peritoneum. Thus, when we are seeing both a mucosal-gas interface and a serosal-gas interface, we are seeing Rigler’s sign. When three loops of bowel touch each other we may see a lucent triangle in the center representing three serosal-gas interfaces; this is known as Rigler’s triangle. This sign is difficult to see unless there is a sufficient amount of free gas. Ability to see the patient’s falciform ligament is another sign indicating free gas. Also, free gas beneath the liver margin in Morrison’s pouch results in a tissue-gas interface with the liver margin as well as lucency that typically is not present on a supine film. Occasionally we see the lateral pelvic ligament, which becomes visible with the presence of sufficient amounts of free gas. CT is considerably more sensitive in the detection of free intraperitoneal gas.