CHAPTER 159

Stroke in Young Adults

Definition

Four percent of strokes in the United States occur in adults younger than 45 years, and a collective review of reports provides estimates that range up to 21% or greater [1]. Although the 28,000 strokes in this age group are a small fraction of the 731,000 total events in the United States each year, stroke is an important cause of neurologic impairment in this group. Stroke occurs in those younger than 45 years more than twice as frequently as spinal cord injury (11,000 per year, all ages), and yet there has been limited awareness in American society of stroke as a disease affecting younger adults. As overall stroke incidence declines, there is evidence that stroke is occurring at a younger age, with the incidence increasing in younger adults [2]. Before the age of 30 years, more women than men have strokes because of the risks of pregnancy, childbirth, and oral contraceptive use [3,4]; this trend reverses with advancing age. In the United States, the incidence of stroke is two to five times higher in young urban blacks and twice as high in Hispanics than in whites [5]. Strokes in young adults are particularly devastating events because they often occur in otherwise healthy-seeming individuals who are in the prime of life and fully involved with family, community, and workplace responsibilities. Young adults also have high expectations of recovery and consequent difficulty in adjusting to residual disability.

Although more than 60 different disorders causing stroke in young adults have been identified, they can be grouped into several broad categories. Atherosclerotic disease accounts for approximately 20%; cardiac emboli, 20%; arteriopathies (particularly large-vessel dissection), 10%; coagulopathy, 10%; and peripartum cerebrovascular accidents, 5%. Another 20% may be related to mitral valve prolapse, migraine, and oral contraceptive use, and 15% remain unexplained after full evaluation [6]. In American studies, illicit drug use has been associated with stroke in 4% to 12% of cases [5,7]. The main clinical challenge in the management of young adults with acute stroke is the identification of its cause. Whereas cryptogenic stroke was the most common cause in the past, today specific causes are more readily identified resultant to improved capability in noninvasive imaging of brain vessels and heart arteries and valves, aortic electrophysiology, and genetic diagnostic instruments developed in recent decades [8,9]. The rate of thrombolysis use among young acute ischemic stroke patients has increased in the past decade, in part owing to stroke center certification and the availability of the stroke networks [10].

Approximately 75% of patients younger than 65 years will survive 5 years or more after their stroke [1]. Individual survival depends, of course, on the specific cause of the stroke and its treatment. In general, two thirds of young survivors achieve good functional recovery, although a history of diabetes mellitus, severe deficit at onset, or stroke involving the total anterior circulation may reduce that likelihood. Overall, the risk for recurrence in those who have suffered a first stroke averages 5% per year and varies with the survivor’s burden of risk factors [11–13].

Symptoms

The presenting neurologic symptoms of stroke are the same in young as in elderly patients and are reviewed in Chapter 158. The clinician caring for young adult stroke survivors in the post-acute phase is likely to encounter, in addition to neurologic residua of the stroke, a number of secondary symptoms that will require ongoing management. The most common of these are emotional effects, pain, spasticity, bladder dysfunction, sexual dysfunction, and fatigue. These symptoms may also occur in older stroke patients; however, this chapter focuses on the impact they have on the young stroke survivor.

Emotional Effects

The common emotional consequences of stroke are depression, emotional lability, and anxiety. Clinical depression occurs in approximately 40% of patients after stroke; its incidence peaks 6 months to 2 years after the ictus. It is more likely in those with a prior history of alcoholism or depression and in patients who have suffered a severe stroke [14,15].

Depression can be difficult to identify in aphasic patients who cannot respond reliably to questions about mood and in patients with motor aprosodia (loss of emotional tone in facial expression and voice) due to right hemispheric stroke. Patients tend to become more socially isolated after stroke because of language, cognitive, and physical deficits. Loss of social interaction and support increases the likelihood of depression. Stress related to marital role reversal after a stroke in one member of a couple is common, as is depression in caregivers [15].

Neurologically mediated emotional lability, also known as pseudobulbar affect or emotional incontinence, in which the patient has abrupt episodes of crying or laughing in response to mention of an affectively charged topic, may be a source of distress to the patient and family. It may also complicate evaluation of the patient’s true emotional state.

Patients may experience heightened anxiety chronically after stroke. In some cases, specific triggers of the anxiety, such as fear of falling while walking with a cane or fear of being left alone, can be identified in the history. The prevalence and severity of anxiety symptoms were comparable to those of depression symptoms, and the prevalence of both mood symptoms was similar during the acute period and 1 year after stroke. Both mood disturbances were also associated with a poorer health-related quality of life at 1 year, whereas only depression symptoms influenced functional recovery. More emphasis should be given to the role of anxiety in stroke rehabilitation interventions [16].

Pain

Pain is a common problem after stroke in young patients. It usually affects the hemiparetic extremities and may be centrally or peripherally mediated. Shoulder pain occurs in up to 85% of stroke patients, usually during the first 6 to 12 months after stroke [17]. The history should address its many potential causes [18] (Table 159.1). In addition, younger individuals with partially recovered motor function may have secondary sprains, tendinitis, skin breakdown, and nerve palsies in the paretic extremities as these are pushed beyond their physiologic limits in the effort to resume normal activities. The normal arm and leg may suffer similar overuse injuries in the course of compensating for the weak side. Heavy use of assistive devices, including canes, walkers, braces, and splints, may contribute to these injuries and consequent pain.

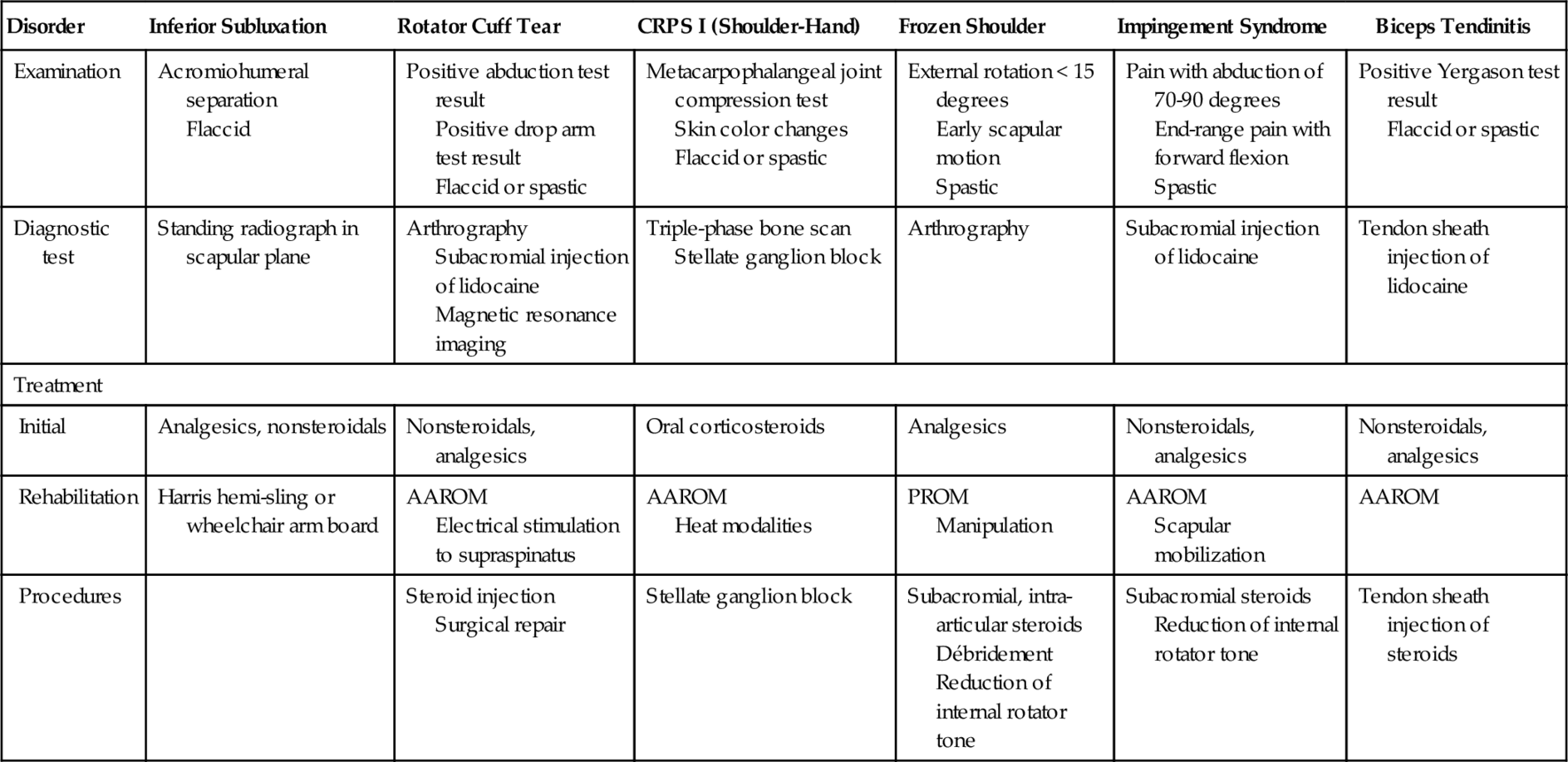

Table 159.1

Post-Stroke Shoulder Pain [18]

| Disorder | Inferior Subluxation | Rotator Cuff Tear | CRPS I (Shoulder-Hand) | Frozen Shoulder | Impingement Syndrome | Biceps Tendinitis |

| Examination | Acromiohumeral separation Flaccid |

Positive abduction test result Positive drop arm test result Flaccid or spastic |

Metacarpophalangeal joint compression test Skin color changes Flaccid or spastic |

External rotation < 15 degrees Early scapular motion Spastic |

Pain with abduction of 70-90 degrees End-range pain with forward flexion Spastic |

Positive Yergason test result Flaccid or spastic |

| Diagnostic test | Standing radiograph in scapular plane | Arthrography Subacromial injection of lidocaine Magnetic resonance imaging |

Triple-phase bone scan Stellate ganglion block |

Arthrography | Subacromial injection of lidocaine | Tendon sheath injection of lidocaine |

| Treatment | ||||||

| Initial | Analgesics, nonsteroidals | Nonsteroidals, analgesics | Oral corticosteroids | Analgesics | Nonsteroidals, analgesics | Nonsteroidals, analgesics |

| Rehabilitation | Harris hemi-sling or wheelchair arm board | AAROM Electrical stimulation to supraspinatus |

AAROM Heat modalities |

PROM Manipulation |

AAROM Scapular mobilization |

AAROM |

| Procedures | Steroid injection Surgical repair |

Stellate ganglion block | Subacromial, intra-articular steroids Débridement Reduction of internal rotator tone |

Subacromial steroids Reduction of internal rotator tone |

Tendon sheath injection of steroids | |

AAROM, active-assisted range of motion; CRPS I, chronic regional pain syndrome type I; PROM, passive range of motion.

Muscle Stiffness due to Spasticity

Stiffness and heaviness of muscles and joints are common complaints of young stroke patients in the post-acute setting. These symptoms are often due to the evolution of muscle tone from the flaccid to the spastic state that occurs during the first several months that follow a stroke. Although it is occasionally helpful in allowing weight bearing on a leg with little voluntary motor return, spasticity more often complicates the patient’s efforts to resume normal motor function. The reader is referred to Chapter 153 for further discussion of spasticity symptoms. Joint stiffness may also be due to contracture, which is shortening of the muscles, ligaments, or tendons around a joint due to rheologic changes in the tissues. This is common in the finger joints of the affected hand. Frozen shoulder, with contracture of the glenohumeral joint capsule, also occurs.

Bladder Dysfunction

Chronically diminished bladder control with urge incontinence occurs commonly in younger stroke patients. The history should ascertain chronicity and frequency of the problem, diurnal pattern, and presence or absence of the sensation of needing to void; a relationship to coughing, laughing, or straining is noted. The patient is queried about abdominal pain and pain on urination.

Sexual Dysfunction

Whether the physiologic process of sexual function changes as a result of stroke, and if so, how it changes, has not been scientifically established. Nonetheless, most patients report diminished sexual function after stroke. This may involve diminished libido or decreased erectile or ejaculatory function. Decreased libido may correlate with the presence of depression and reduced physiologic sexual function with medical comorbidity. Neither clearly relates to size or location of stroke. There is evidence that patients’ partners play a significant role in the decline of sexual activity, through fear of relapse, anguish, and lack of excitation. A small number of patients report increased libido after stroke, and rarely, troublesome hypersexuality appears [19,20]. The history should note change in interest and frequency of sexual activity, alteration in ability to achieve erection or ejaculation in men and lubrication or orgasm in women, and presence of depression or active medical comorbidities that may influence sexual activity level. Medications are reviewed for antihypertensives, antidepressants, and others that may hinder sexual function and possibly fertility, although there is little research on this topic.

Fatigue

Increased fatigue after stroke has been reported in 39% to 68% of patients in published series. It is frequently influenced by coexisting depression. Young adults who never before needed naps now do. Patients become fatigued, physically and mentally, with less effort than before the stroke. Return to active work and family life may be limited by fatigue [21,22]. The history should document a change in fatigue level after the stroke and probe the daily pattern of fatigue and sleep for symptoms of insomnia, sleep apnea, and the many medical conditions that produce fatigue. Medications are reviewed to identify sedative agents. Depression and loss of physical conditioning may affect energy levels, as may the increased energy cost of hemiplegic gait [23].

Physical Examination

In the post-acute setting, the examination of the younger patient after a stroke includes neurologic and functional status for evidence of improvement or deterioration. Improved motor control in the affected leg may allow trimming back of a brace and progression in gait training to a less supportive assistive device. Worsening motor or sensory function, on the other hand, may signal not only further cerebral events but also the presence of a systemic illness, medication intolerance, new peripheral nerve injuries related to positioning or assistive devices, or worsening neuropathy. Confrontation testing for visual fields and double sensory stimulation tests for visual and tactile neglect provide important information to the patient and physician about suitability for community mobility, particularly driving. Clock drawing, target cancellation, line bisection, and reading from a magazine can be quickly performed in the office and provide additional information about neglect and attention. The Mini-Mental State Examination is a rapid and helpful cognitive screen [24,25]. The affected arm and leg should be inspected for skin breakdown. Maceration of the palm in a tightly flexed hand and friction marks on the dorsum of the foot and calf of patients using ankle-foot orthoses are common. Ulnar palsy and olecranon bursitis related to a constantly flexed spastic elbow can occur. It is particularly important to identify and to treat these problems early in patients with diminished sensation.

Signs of unusual causative entities should be sought if the etiology of the stroke is unclear. These may include the skin laxity and hypermobility of Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, the ipsilateral ptosis and miosis (partial Horner syndrome) associated with carotid dissection, the multiple venipuncture marks of intravenous drug abuse, the livedo reticularis of Sneddon syndrome, the vasculitic rash of connective tissue diseases, and the arachnodactyly and tall habitus of Marfan syndrome.

Emotional Effects

Mood should be evaluated for signs of depression, lability, and anxiety. For patients with intact verbal function, the two questions During the past 2 weeks, have you felt down, depressed, or hopeless? and During the past 2 weeks, have you felt little interest or pleasure in doing things? may be as helpful as more extensive screening tools, such as the depression screening criteria of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders [26,27]. In severely aphasic patients, the screen must, of necessity, consider facial expression, gestures, and posture and the reports of caretakers regarding appetite, sleep, and mood. If the caretaker shows signs of depression, it may be helpful to offer him or her referral for further evaluation. Lability can often be elicited by discussing affectively relevant topics, such as children or spouse. Physical examination signs of chronic anxiety may include hunched posture, fleeting eye contact, cold or moist hands, mild tachycardia, rapid and hypophonic speech, and ready startle reaction.

Pain

The examination addresses appearance, tenderness, pain pattern, and range of motion of the painful regions, looking for signs of specific medical and musculoskeletal disorders. See Table 159.1 for helpful physical examination signs in the diagnosis of post-stroke shoulder pain.

Muscle Stiffness due to Spasticity

Muscle tone at the shoulder adductors, elbow flexors and extensors, wrist and finger flexors, knee extensors, and ankle plantar flexors should be assessed and recorded at each visit with use of the Ashworth scale (Table 159.2). Pain encountered on range of motion is recorded. Reflexes are evaluated, assessing for sustained clonus, which at the ankle and knee can compromise gait and at the wrist and fingers may be mistaken for seizure activity.

Table 159.2

Modified Ashworth Scale for Measurement of Spasticity

| 0 | No increase in muscle tone |

| 1 | Slight increase in muscle tone, manifested by a catch and release or by minimal resistance at the end range of motion |

| 1 + | Slight increase in muscle tone, manifested by a catch, followed by minimal resistance throughout the remainder (less than half) of the range of motion |

| 2 | More marked increase in muscle tone through most of the range of motion, but the affected part is easily moved |

| 3 | Considerable increase in muscle tone, passive movement difficult |

| 4 | Affected part is rigid in flexion or extension |

Bladder Dysfunction

Palpatory examination of the abdomen may reveal suprapubic tenderness due to cystitis or an enlarged bladder indicative of retention with overflow incontinence.

Sexual Dysfunction

Full gynecologic and urologic examinations will screen for infectious, traumatic, neoplastic, and hormonal causes of sexual dysfunction in young stroke survivors. The neurologic examination may reveal a neuropathy (manifested by decreased sensation in the feet or hands, decreased ankle and knee reflexes, and occasionally distal weakness) that may be affecting sexual function.

Fatigue

Idiopathic post-stroke fatigue is a diagnosis of exclusion. The examination must screen the patient for the many illnesses that cause fatigue. Among the more prominent of these in this population are Epstein-Barr viral disease, sleep apnea, allergic rhinitis, anemia, dehydration, cerebral hypoperfusion, hypothyroidism, depression, malignant neoplasia, and medications.

Functional Limitations

Driving

Return to driving is a necessary step for return to a normal lifestyle and avoidance of social isolation in many communities. Once they have been discharged home, young adult stroke patients are generally eager to resume driving. Many rehabilitation clinics offer written tests of driving ability. Although these have not been shown to be adequate predictors of on-the-road performance, they serve a useful screening purpose. Recent work with a computerized driving simulator suggests that these may be helpful and safe tools for retraining of driving skills [28]. A number of factors have been shown to predict driving performance after stroke; right hemisphere location of stroke, visual-perceptual deficits, reduced sustained and selective attention, impulsivity, poor judgment, and lack of organizational skills all correlate with poor performance behind the wheel. Aphasia, although it may have a negative impact on performance on written and road tests because of compromised processing of verbal instructions, does not always interfere with self-directed driving.

Physicians are often consulted about a patient’s readiness to resume driving; visual acuity and fields can be readily screened in an office setting, but evaluation for impulsivity, judgment, and selective and divided attention is more difficult. An on-the-road test performed either by a driving instructor or by the state licensing agency remains the “gold standard” for assessment of driving ability.

Return to Work

The ability to perform valued work is central to self-esteem and an important goal for most young stroke patients. Between 11% and 85% of patients achieve this goal; the wide range reported in this literature is due to differing age ranges, definitions of work, and disability compensation systems [29]. Of those who return to work after stroke, 70% do so at a reduced level. Factors predictive of success in return to work include pure motor or no hemiparesis, good self-care and mobility function at completion of rehabilitation, no aphasia or apraxia, advanced education, and a white-collar job. Barriers to successful vocational rehabilitation include, in addition to the reverse of these factors, cognitive impairment, visual-perceptual impairment, age older than 55 years, and economic disincentives related to disability and retirement benefits.

Patients who are able to resume work after a stroke on average do so within the first 6 months. The 1990 Americans with Disabilities Act has had a positive impact on employers’ responsiveness to the requests of stroke survivors for job accommodations, not only regarding physical access and equipment but also for personal assistance, schedule flexibility, and task modification [29–31]. Most patients return to their previous employer, although young stroke survivors with minimal cognitive impairment may be able to take on new jobs.

Parenting

The young adult stroke survivor who needs to return to parenting faces particular challenges in the performance of child bathing, dressing, feeding, and transporting tasks. Problem solving of these tasks can be done with the assistance of other adult family members, home care occupational therapists, or hired child care assistants. Many helpful items of equipment are readily available (paper disposable diapers with easy to close tabs, microwaves for heating bottles, baby tub inserts). Even when frequent assistance is needed, the patient should be encouraged to assume the supervisory role in child care.

Diagnostic Studies

Because the use of illicit drugs has been linked to strokes in younger individuals, ongoing drug screening in the post-acute setting may occasionally be indicated. Despite the use of early and advanced neuroimaging techniques along with improved symptom recognition by patients, misdiagnosis of acute stroke in young adults in emerging reports occurs at 14%, with posterior circulation more likely to be misdiagnosed as peripheral vertigo. The initial misdiagnosis results in a potential lost opportunity for thrombolysis or admission to certified stroke centers in otherwise good candidates [32]. For other diagnostic testing, see Chapter 158.

Treatment

The patient’s motivation to comply with treatment for hypertension and diabetes, to develop a habit of compliance with newly prescribed anticoagulation therapy, to quit smoking, to avoid excessive alcohol intake, and to turn away from the use of street drugs will be maximal in the months that follow the stroke. Some available studies suggest that stroke rehabilitation should provide interventions designed especially for young adults, but more recent studies reflect that the young adult patient’s needs are similar to those of the general stroke population [33].

Emotional Effects

Initial

Post-stroke depression responds to antidepressant medications of several classes. The lower cardiac risk profile of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors makes them an attractive option for patients with arrhythmia. They should be used with caution in patients with sexual dysfunction. The sedative and urinary retentive properties of tricyclic antidepressants may be helpful for patients with concomitant neuropathic pain, excessive salivation, and sleep disturbance or urge incontinence. All of the major classes of antidepressants have the potential to lower seizure threshold. The family and community, including local and national stroke support and education groups, are important resources for the young patient who is struggling with emotional adjustment to residual disability and altered lifestyle. Referral to a psychiatrist, psychologist, home care social worker, or psychiatric nurse is often helpful. Emotional lability often responds to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and usually diminishes over time [34,35]. Management of anxiety in cognitively impaired young stroke patients should emphasize the less sedating anxiolytics, counseling, and environmental manipulation to reduce known triggers.

Rehabilitation

Neurologic and functional improvement is perhaps the best antidote to post-stroke depression. A multidisciplinary stroke rehabilitation program, by providing graded and progressive activities in many areas, gives the patient the opportunity to make and to appreciate numerous improvements in parameters of mobility, self-care, language, and cognition. Therapists are skilled at providing encouragement and positive reinforcement for successes, large and small, in the targeted activities. The rehabilitation therapy environment provides substantial psychological support to the patient, and it is common for depression first to become evident, or to worsen, at the time outpatient therapy finishes and this support system is withdrawn.

Procedures

Electroconvulsive therapy may be indicated for refractory depression.

Pain

Initial

Measures for soft tissue–based pain include non-narcotic analgesics and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, with care taken to consider the cardiac, renal, hepatic, and gastrointestinal risks. When narcotic medication for pain relief is required, the fentanyl transdermal patch is a useful option. Neuropathic and central pain syndromes often respond to gabapentin. See Table 159.1 for treatment options for the several varieties of post-stroke shoulder pain.

Rehabilitation

Rehabilitation treatment of pain syndromes is useful both in itself and because it allows close monitoring by a qualified therapist of the patient’s symptoms and response to treatments. Soft tissue injuries often respond to stretching and strengthening, positioning, electrical stimulation of the affected muscles, and heat modalities including hot packs and ultrasound when sensation is adequate to allow their use. Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation and functional electrical stimulation to the supraspinatus and upper trapezius are often helpful in poorly defined shoulder pain, as are arm slings, such as the Harris hemi-sling, that promote optimal glenohumeral alignment.

Procedures

Acupuncture can be beneficial for central pain syndromes, and subacromial bursa steroid injection will help approximately half of patients with post-stroke shoulder pain. Botulinum toxin and phenol injections provide relief when pain is due to spasticity in specific muscles.

Surgery

In post-stroke shoulder pain, surgical repair may be considered when rotator cuff tear can be established as the cause. Surgical débridement may be required for severe, unremitting frozen shoulder.

Muscle Stiffness due to Spasticity

Initial

The management of muscle stiffness due to spasticity is discussed in detail in Chapter 153. Intercurrent infections, localized sores, stress, and anxiety can worsen spasticity and should be treated before other interventions are added. Sedation in this cognitively fragile population is to be avoided and limits dosage titration of all the available antispasticity agents. Tizanidine and gabapentin, because of their analgesic as well as muscle relaxant actions, are logical choices for painful spasticity. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors occasionally exacerbate spasticity.

Rehabilitation

Mild post-stroke spasticity in the heel cord and finger and wrist flexors can often be adequately controlled with a stretching program performed two or three times per day by the patient. Range of motion in a spastic ankle or hand can be preserved with nighttime use of custom-fabricated resting splints.

Procedures

Injection of spastic muscles with botulinum toxin and of peripheral motor nerves with phenol can enhance gait pattern and hand function and reduce pain in young stroke survivors. Once a pattern of useful response to injection to specific muscles and nerves has been established, consideration should be given to surgical referral for more permanent intervention.

Surgery

Tendon lengthening, sectioning, and transfers infrequently performed in elderly stroke patients because of limited life expectancy and medical risks should be considered in younger patients when the pattern of hypertonicity has stabilized. Achilles tendon lengthening may allow improved heel strike in patients with chronic equinovarus posturing due to spastic triceps surae. Sectioning of short toe flexors can reduce painful toe clawing, and splitting and lateral reattachment of a portion of the anterior tibial tendon (SPLATT procedure) can rebalance a varus foot. Electrophysiologic evaluation of the extremity in a gait laboratory can provide useful information to supplement the physical examination and help ensure that the optimal muscles are targeted for surgical intervention.

Bladder Dysfunction

Initial

For the stroke survivor with urge incontinence due to spastic neurogenic bladder, helpful medications are available. The anticholinergics oxybutynin and tolterodine are first-line agents for management of detrusor instability. In addition, tricyclic antidepressants provide mild anticholinergic stimulation and can be used to increase bladder capacity.

Rehabilitation

Urinary incontinence can be successfully managed in the inpatient rehabilitation setting or at home with timed voiding (every 2 hours while awake), timed fluid intake (none after supper), use of padded clothing or condom catheter, and a commode or urinal by the bedside.

Pelvic floor strengthening exercises are helpful for stress incontinence. There are no specific rehabilitation treatments for detrusor instability, although the patient’s therapists are often in a position to observe and to document the extent of the problem.

Surgery

Bladder suspension surgery may be indicated for stress incontinence.

Sexual Dysfunction

Treatment of depression with medications such as bupropion, mirtazapine, and nefazodone, which do not hinder sexual function [36], and of active concurrent medical illnesses can promote improved sexual function. Elimination of other medications that compromise ejaculatory or orgasmic function will obviously help as well. Treatment with testosterone to enhance libido and with sildenafil to improve erection or estrogen to improve lubrication may be considered.

Fatigue

Initial

Efforts to ensure a normal sleep-wake cycle should be made. These include maintenance of a consistent and appropriate bedtime, avoidance of stimulant beverages late in the day, and use of hypnotic agents at bedtime, if needed. For the patient who sleeps well at night but remains easily fatigued during the day, a trial of methylphenidate on arising and at noon may be considered. Loss of initiation due to frontal lobe disease may be perceived as fatigue and occasionally responds to amantadine. For the depressed patient with fatigue, a nonsedating antidepressant should be chosen. Short daytime naps in patients with normal nighttime sleep pattern should not be discouraged.

Rehabilitation

A tailored cardiovascular conditioning program is helpful to maximize the patient’s aerobic capacity and physical stamina. Patients with significant physical impairment will benefit from a physical therapist’s assistance in designing an adapted conditioning program, which may emphasize use of a stationary bicycle, arm ergometer, and therapeutic pool. Patients with limiting cardiovascular comorbidities will require the physician’s input for heart rate and blood pressure guidelines. Appropriate bracing and use of assistive devices and gait training by an experienced physical therapist can help reduce the energy cost of hemiplegic gait. For some patients, wheelchair propulsion is less fatiguing than walking.

Potential Disease Complications

The spectrum of neurologic and medical complications of stroke in young adults is similar to that in older stroke patients. See Chapter 158.

Potential Treatment Complications

Complications of stroke treatment are similar in young and older adults. They are discussed in Chapter 158.