CHAPTER 157

Spinal Cord Injury (Lumbosacral)

Definition

Lumbosacral spinal cord injury (SCI) refers to impairment or loss of motor or sensory function in the lumbar or sacral segments of the spinal cord, secondary to damage of neural elements within the spinal canal [1]. With this level of injury, arm and trunk functions are spared, but the legs and pelvic organs are involved.

The terms lumbosacral SCI and paraplegia are also used in referring to conus medullaris and cauda equina injuries but not to impaired sensorimotor function due to neural involvement outside the spinal canal (as in lumbosacral plexus lesions or injury to peripheral nerves). Conus medullaris syndrome results from an injury to the sacral spinal cord (conus) and lumbar nerve roots within the spinal canal. Cauda equina syndrome refers to injury to the lumbosacral nerve roots within the neural canal.

Lumbosacral injuries account for about 11% of SCI cases in the national Spinal Cord Injury Model Systems database [2]. The most common causes of injury include motor vehicle crashes, falls, acts of violence, and recreational sporting activities [3,4]. There is an association between level of injury and cause of injury, and acts of violence are more often associated with paraplegia than with cervical injury and tetraplegia [2].

Neurologic versus Skeletal Level of Injury

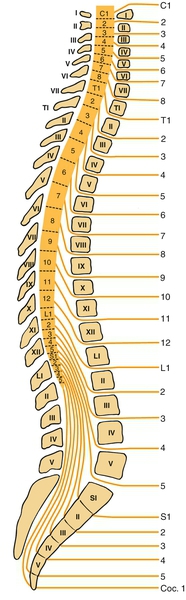

Lumbosacral SCI refers to the neurologic level of injury, which is different from the skeletal level of injury. Because of the discrepancy between the lengths of the spinal cord and the vertebral column, the L1-L5 lumbar spinal cord segments are typically located at the T11-T12 vertebral level, and the S1-S5 sacral spinal cord segments are at the L1 vertebral level. The spinal cord ends between T12 and L2 (most often at L1 vertebra), and injury within the neural canal below that bone level involves the cauda equina. Lesions at the level of the lowermost thoracic and first lumbar vertebrae may result in mixed cauda equina and conus medullaris lesions (Fig. 157.1).

Symptoms

Lumbosacral SCI may be manifested with weakness in the lower extremities, numbness and tingling, bladder and bowel disturbances (urinary retention, constipation, bladder or bowel incontinence), impotence, back pain, and burning perianal or lower extremity pain.

In the outpatient setting, patients may also present with secondary conditions and associated problems, such as urinary tract infections or pressure ulcers. Patients with SCI may have vague, atypical, or nonspecific symptoms. Classic symptoms of urinary tract infection, such as urinary frequency, urgency, and dysuria, may be absent, and patients may present instead with an increased frequency of spontaneous voiding or increased muscle spasms [5]. Fever and malaise may be indicative of a urinary tract infection but can also be due to other infections (such as osteomyelitis underlying a pressure ulcer) or noninfectious causes, such as osteoporotic long bone fracture, deep venous thrombosis, heterotopic ossification, or drug fever (e.g., due to antibiotics). Unilateral leg swelling may be the only presentation of osteoporotic lower limb fractures but could also be due to deep venous thrombosis, heterotopic ossification, hematoma, or cellulitis in the setting of SCI [6].

Pain is a common symptom in people with SCI, and some studies suggest that pain prevalence may be even higher with paraplegia than with cervical injury and tetraplegia [7,8]. A comprehensive history of pain characteristics is needed to accurately determine the underlying cause, which may be nociceptive, neuropathic, or a combination of both.

New weakness or sensory deficits in the upper extremities may indicate post-traumatic syringomyelia extending into the cervical spinal cord or a peripheral nerve entrapment, such as the median nerve at the carpal tunnel or ulnar nerve at the elbow [9]. Patients with chronic SCI who present with extension or worsening of lower extremity weakness or numbness may have post-traumatic syringomyelia or spinal cord or nerve root compression due to progressive spinal deformity or instability.

Rectal bleeding is often caused by hemorrhoids but may be a manifestation of more serious disease, such as colorectal cancer [10]. Similarly, hematuria may be due to urinary tract infection, stones, or catheter-induced trauma, but bladder cancer should be considered in the differential diagnosis, especially in smokers and those with chronic indwelling bladder catheters [5].

Mood disturbances are common in SCI [11]. Depression may be manifested with somatic symptoms such as appetite change and sleep disturbance, although symptoms like loss of energy may be difficult to interpret in the setting of SCI [11,12]. Because many medical diseases may produce similar somatic symptoms, it is helpful to inquire about specific symptoms typically associated with depression, such as suicidal thoughts, dysphoria, and feelings of hopelessness and worthlessness. Early morning awakening is suggestive of primary depression, and fatigue caused by depression is often worse in the morning.

Physical Examination

Spinal Inspection and Palpation

There may be reduced lumbar lordosis due to muscle spasm from pain. Spine fractures may result in deformity, and palpation may reveal areas of tenderness.

Evidence of Concurrent Injuries

Concurrent injuries, including head injury, extremity fractures, and abdominal visceral injury, may accompany lumbosacral SCI and should be considered during diagnostic examination.

Neurologic Examination

Neurologic examination is conducted in accordance with the International Standards for Neurological and Functional Classification of Spinal Cord Injury published by the American Spinal Injury Association [1]. The neurologic findings may sometimes be subtle (e.g., limited to perineal anesthesia or urinary retention) and can be missed in the setting of acute trauma with routine placement of an indwelling catheter or drug-induced sedation, unless they are carefully considered [13]. The neurologic examination should be repeated at regular intervals to monitor for improvement or deterioration [14].

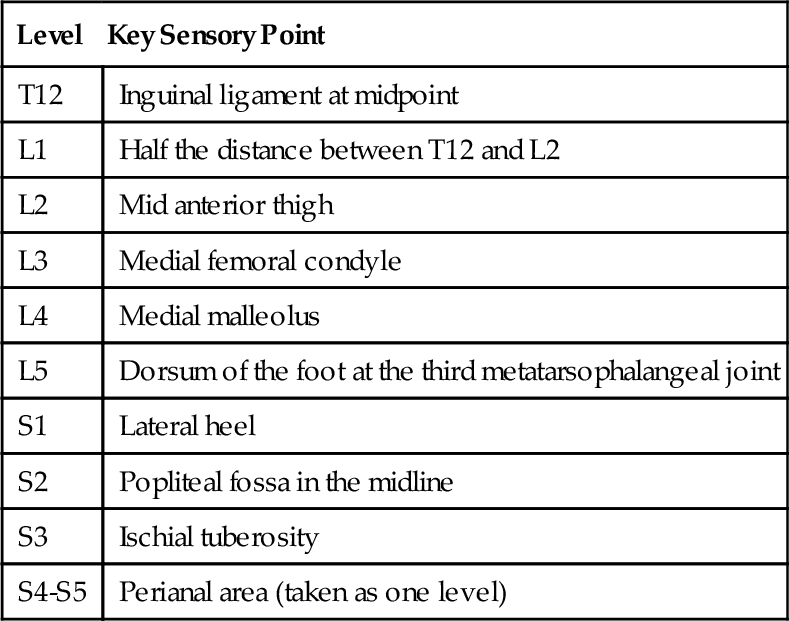

Sensory Examination

The required portion of the sensory examination is completed through testing of key points in each dermatome on the right and left sides of the body (Table 157.1) for pinprick (tested with a disposable safety pin) and light touch sensation (tested with cotton). Pinprick and light touch sensation are separately scored at each key point on a 3-point scale: 0, absent; 1, impaired; and 2, normal. In testing for pinprick sensation, inability to distinguish dull from sharp sensation is graded 0.

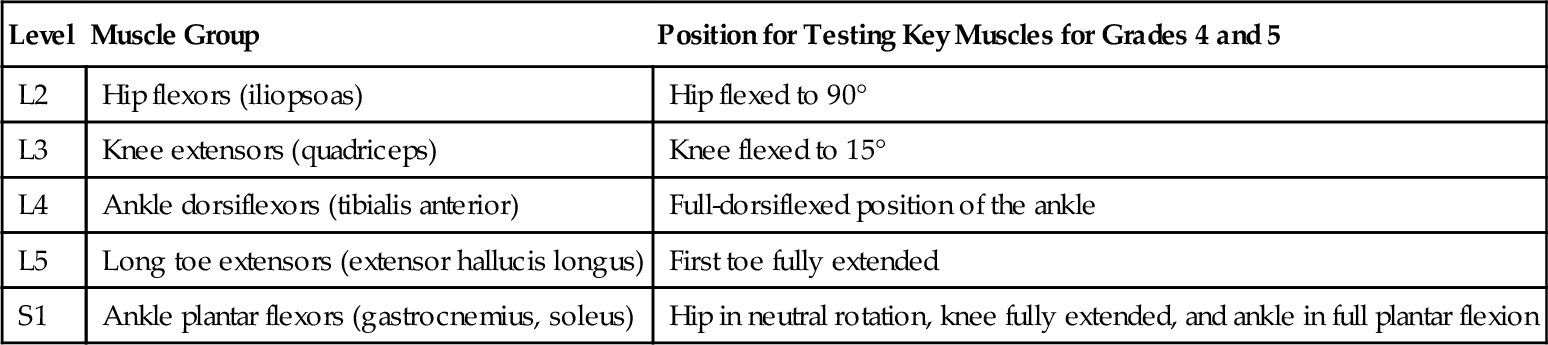

Motor Examination

Muscle strength is graded on a 6-point scale of 0 to 5; 0 is no contraction and 5 is normal strength. For the lumbosacral myotomes, five key muscle groups are tested bilaterally (Table 157.2).

Neurologic Rectal Examination

Neurologic rectal examination includes determination of deep anal sensation and testing for voluntary contraction of the external anal sphincter around the examiner’s finger (graded as present or absent). If there is voluntary contraction of the anal sphincter, the patient has a motor incomplete injury.

Additional Neurologic Examination

In addition to these required elements for neurologic classification of SCI, position and deep pressure sensation and muscle strength of additional lower extremity muscles, such as medial hamstrings and hip adductors, are also tested. Examination also includes assessment of muscle stretch reflexes, muscle tone, anal sphincter tone, bulbocavernosus reflex, and plantar reflexes.

Conus Medullaris and Cauda Equina Injuries

The examination will vary with the level of damage and the relative involvement of the conus and cauda equina and may include evidence of lower or upper motor neuron involvement. Patients with injury above the conus medullaris typically present with signs consistent with upper motor neuron or suprasacral SCI, whereas those with injury below this level present with a clinical picture consistent with lower motor neuron impairment. Lesions affecting the transition between the two regions (typically around L1 vertebral-level injury) can have a mixed picture. Conus medullaris lesions typically result in impaired sensation over the sacral dermatomes (saddle and perineal anesthesia), lax anal sphincter with loss of anal and bulbocavernosus reflexes, and sometimes weakness in the lower extremity muscles. Cauda equina involvement results in asymmetric atrophic, areflexic paralysis, radicular sensory loss, and sphincter impairment [1,13].

Skin Examination

Skin examination is conducted with particular attention to the areas most vulnerable to pressure ulcer development. These include the sacrum-coccyx, heels, trochanters, and ischial tuberosities [15].

Functional Limitations

Lumbosacral SCI can result in significant functional deficits. These include impaired mobility due to lower extremity paralysis and bladder, bowel, and sexual dysfunction due to autonomic dysregulation.

Expected Functional Outcomes

Predictions of function can be based on completeness and level of injury. The Consortium for Spinal Cord Medicine has developed clinical practice guidelines on outcomes after SCI with expected functional outcomes for each level of injury in a number of domains [14]. Expected outcomes for complete lumbosacral SCI are summarized in Table 157.3.

Table 157.3

Expected Functional Outcomes for Motor Complete Lumbosacral Spinal Cord Injury

| Domain | Expected Functional Outcome | Equipment |

| Bowel | Independent | Padded toilet seat |

| Bladder | Independent | |

| Bed mobility | Independent | Full to king size standard bed |

| Bed and wheelchair transfers | Independent | |

| Pressure relief | Independent | Wheelchair pressure relief cushion |

| Wheelchair propulsion | Independent indoors and outdoors | Manual lightweight wheelchair |

| Standing and ambulation | Standing: independent Ambulation: functional, some assist to independent L1-L2: household ambulation L3-S5: community ambulation |

Standing frame Knee-ankle-foot orthosis or ankle-foot orthosis Forearm crutches or cane as indicated |

| Eating, grooming, dressing, and bathing | Independent | Padded tub bench Hand-held shower |

| Communication | Independent | |

| Transportation | Independent in car, including loading and unloading wheelchair | Hand controls |

| Homemaking | Independent complex cooking and light housekeeping, some assist with heavy housekeeping |

Modified from Consortium for Spinal Cord Medicine. Outcomes Following Traumatic Spinal Cord Injury. Clinical Practice Guidelines for Health Care Professionals. Washington, DC, Paralyzed Veterans of America, 1999.

Ambulation

Persons with lumbosacral SCI should generally be independent at the wheelchair level and have the greatest potential for ambulation. If hip flexors and knee extensors demonstrate even minimal strength in the first few days after injury, functional recovery and community ambulation are likely. It has been reported that to ambulate independently after SCI, individuals need pelvic control, grade 3/5 (antigravity) hip flexor strength bilaterally to advance the lower extremities, and antigravity knee extensor strength on at least one side (so that no more than one knee-ankle-foot orthosis is needed) [16]. There is individual variation and additional factors than have an impact on ambulation outcome, but patients with motor complete lumbosacral SCI at the L1-L2 level can in general be expected to be household ambulators; community ambulation is an appropriate goal at L3-S5 levels. The lower extremity motor score can predict the likelihood of ambulation. In those with complete paraplegia, chance of walking at 1 year is less than 1% with a 30-day score of 0 and 45% with a score of 1 to 9. In those with incomplete paraplegia, chance of walking at 1 year is 33% with a score of 0, 70% with a score of 1 to 9, and 100% with a score above 10 [16].

Bowel, Bladder, and Sexual Dysfunction

Bowel, bladder, and sexual dysfunction may be significantly disabling in these patients. SCI above the sacral segments is typically associated with an upper motor neuron or reflexic bowel; lesions involving the S2-S4 anterior horn cells or cauda equina have areflexic or lower motor neuron bowel characterized by slow stool propulsion, dry and round stool referred to as scybalous, and risk of incontinence due to denervation of the external anal sphincter [10,17]. Depending on the location of injury and the extent of upper and lower motor neuron impairment, hyperreflexic, areflexic, or mixed type of neurogenic bladder may occur. Absent bulbocavernosus reflex and muscle stretch reflexes in the lower extremities suggest the likelihood of lower motor neuron impairment of the bladder and bowel. Sexual dysfunction is frequent [18]. Men with SCI at the sacral level often lose ability to have reflex erections, although psychogenic erections may be preserved in some. Ejaculation is often impaired, but it may be preserved in a higher proportion of those with incomplete lower motor neuron injuries.

Factors Affecting Functional Outcomes

Pain, whether nociceptive or neurogenic, may interfere with function [7,19]. Neuropathic pain is more common with cauda equina injuries than with injury limited to the conus medullaris. Age, concurrent injuries or comorbidities, body habitus, psychosocial and cultural factors, and personal goals and motivation can significantly affect functional outcomes.

Diagnostic Studies

Spinal Imaging

Radiologic and laboratory studies are used to localize the site of the pathologic change and the underlying cause [13]. Plain radiographs typically include anteroposterior, lateral, and oblique views. The entire spine should be visualized because multiple levels of injury are not unusual. Computed tomographic scanning allows optimal visualization of bone injury and canal occlusion due to bone fragments. Magnetic resonance imaging is especially helpful because of its ability to visualize the soft tissues, including ligamentous structures, intravertebral discs, epidural or subdural hematomas, and hemorrhage or edema in the spinal cord. Magnetic resonance imaging with gadolinium is helpful in diagnosis of post-traumatic syringomyelia.

Electrodiagnostic Testing

Electromyography and nerve conduction studies may be helpful in distinguishing lesions of the spinal cord or cauda equina from those of the lumbar plexus or peripheral nerves.

Urologic Studies

Urodynamic studies are useful to assess the type and extent of neurogenic bladder and sphincter dysfunction. Periodic cystoscopy may be indicated in those with chronic indwelling urinary catheters because of increased risk of bladder cancer [20]. Studies to evaluate upper urinary tracts in patients with neurogenic bladder include renal ultrasonography, renal scan, abdominal radiography, and abdominal computed tomography, but there is no current consensus on the type, indication, or frequency of these tests.

Treatment

Initial

Initial management [13] of anyone thought to have sustained spinal injury includes adequate spinal immobilization, with placement on a board in the neutral supine position. Stabilization of the airway and hemodynamic status takes precedence in the setting of acute trauma. Methylprednisolone has been advocated in patients presenting within 8 hours of SCI, although effectiveness of this pharmacologic intervention is not uniformly accepted.

Rehabilitation

Information about potential for motor recovery can be used to set functional goals and to plan for equipment needs (see Table 157.3), keeping in mind that individual factors and coexisting conditions may affect achievable goals [14]. Important elements of rehabilitation include an interdisciplinary approach, establishment of an individualized rehabilitation program with consideration of unique barriers and facilitators, and inclusion of the patient as an active participant in establishment of goals [16].

Bowel Management

An individualized bowel care program should be established [10,17]. For upper motor neuron (reflexic) bowel dysfunction, this includes digital rectal stimulation. For lower motor neuron (areflexic) bowel dysfunction, reflex stimulation will not be effective; digital manual evacuation by gloved lubricated fingers is needed, along with Valsalva maneuver or abdominal massage to increase pressure around the colon to push the stool out. Manual disimpaction is aided by use of bulking agents to keep stool consistency firm.

Bladder Management

Optimal bladder management minimizes urinary tract complications, preserves upper urinary tracts, and is compatible with the individual’s lifestyle [20]. Because hand function is intact in individuals with lumbosacral injuries, they should be able to perform intermittent catheterization if it is needed for bladder management. If there is abnormal urethral anatomy, poor cognition or unwillingness to adhere to the catheterization schedule, or high fluid intake with consistently large bladder volumes, indwelling catheterization may be needed. Condom catheters can be an appropriate option for urinary drainage in men, provided low-pressure and complete voiding can be documented. For patients with lower motor neuron injuries with low outlet resistance, the use of Credé and Valsalva maneuvers may be considered.

In patients with suspected urinary tract infection, empirical antibiotic treatment may be started while waiting for urine culture results and modified as needed once results are available [5]. The presence of urinary tract obstruction, stones, reflux, abscess, or prostatitis should be considered if the patient fails to respond to antibiotic therapy or has a rapid recurrence with the same organism. Use of prophylactic antibiotics is usually not warranted but should be considered before urologic testing that involves instrumentation, especially in the presence of bacteriuria. Antibiotics to treat asymptomatic bacteriuria in patients with chronic indwelling bladder catheters are generally not indicated.

Pain and Spasticity

Nociceptive causes of pain should be identified and addressed [19]. Many medications, including anticonvulsants and tricyclic antidepressants, have been tried and may help in management of neuropathic pain after SCI, but none has been shown to be consistently effective. Nonpharmacologic interventions and education of the patient are important and should not be ignored. Transcutaneous nerve stimulation may help pain originating at the level of injury. Opioid prescription may be needed for pain unresponsive to other measures. Minimization of extreme or potentially injurious positions at all joints, reduction in the frequency of repetitive upper extremity tasks, proper instruction in transfer techniques to minimize upper extremity injury, optimal wheelchair selection and training, and incorporation of upper body flexibility and resistance exercises are important in preserving upper extremity function and reducing chronic pain due to upper extremity overuse [21].

Spasticity is less of a problem in lumbosacral SCI than in cervical or high thoracic injuries. Management of spasticity [22] includes elimination of the underlying noxious stimulus, use of physical interventions, systemic medications, chemical denervation, intrathecal agents, and rarely orthopedic or neurosurgical procedures. Nonpharmacologic interventions include positioning and stretching (e.g., prone lying to stretch hip flexors and stretching of hamstrings and heel cords to prevent tightness and contractures). Several medications are used for treatment of SCI-related spasticity, including baclofen, tizanidine, gabapentin, and benzodiazepines [23].

Pressure Ulcer Prevention

Education of the patient is critical in this area (see Chapter 148). Avoidance of prolonged positional immobilization, institution of pressure relief, and prescription of pressure-reducing seating systems and support surfaces are important in prevention of pressure ulcers. Daily comprehensive skin inspections should be carried out with particular attention to vulnerable insensate areas (e.g., sacrum-coccyx, ischii, trochanters, heels). Adequate nutritional intake and smoking cessation should be stressed [15].

Procedures

Spasticity

Motor point or nerve blocks with phenol or alcohol may be helpful in treatment of localized lower extremity spasticity (e.g., for hip adductors or ankle plantar flexors) that interferes with positioning, mobility, or hygiene. Intramuscular injections of botulinum toxin are another option.

Pain

Shoulder pain due to subacromial bursitis may be temporarily responsive to local corticosteroid injections, as is the discomfort from carpal tunnel syndrome.

Pressure Ulcers

Sharp débridement of pressure ulcers may be done at the bedside to remove necrotic tissue, although if it is extensive, débridement may need to be done in the operating room.

Surgery

Spine

When thoracolumbar fractures associated with lumbosacral SCI are accompanied by mechanical instability, pain, deformity, or progressive neural impairment, surgical decompression and segmental instrumentation may be indicated for reconstruction of spinal alignment, stability, and early mobilization [13,24]. The ideal timing of and indications for surgical intervention remain controversial.

Pressure Ulcers

Plastic surgery may be indicated for deep pressure ulcers. This includes excision of the ulcer and surrounding scar and muscle and musculocutaneous flap closure [4].

Upper Extremity Pain

Surgery may sometimes be considered for chronic upper extremity overuse-related symptoms that are unresponsive to medical and rehabilitative treatment (e.g., for carpal tunnel syndrome or rotator cuff disease). Outcomes are often poor, especially if upper extremity overuse continues [21].

Bladder and Bowel Dysfunction

Surgical treatment of urolithiasis includes cystoscopic removal of bladder stones, lithotripsy, and percutaneous nephrolithotomy for larger renal stones. Endourethral stents or transurethral sphincterotomy may be considered in individuals with detrusor-sphincter dyssynergia [20]. Patients with neurogenic bowel who have significant difficulty or complications with typical bowel care may be candidates for colostomy. This decision requires careful selection of the patient and individualization to make sure that it is appropriate [17].

Post-traumatic Syringomyelia

Surgical placement of shunts may be indicated for post-traumatic syringomyelia associated with intractable pain or progressive neurologic decline.

Potential Disease Complications

Patients with lumbosacral SCI are prone to multiple complications. Urinary tract infections and pressure ulcers are two of the most common causes of hospitalization in individuals with paraplegia and can result in systemic sepsis [25]. Delayed neurologic deterioration may be due to spinal instability, progressive spinal deformity, or post-traumatic syringomyelia. Upper extremity overuse can result in shoulder pain due to rotator cuff injury or entrapment neuropathies, such as carpal tunnel syndrome [21]. Lower extremity joint contractures (e.g., of the heel cords) can interfere with mobility and with wheelchair positioning. Untreated high bladder pressure in patients with detrusor-sphincter dyssynergia or low bladder compliance may result in upper urinary tract damage. Potential complications of neurogenic bowel include anorectal problems (hemorrhoids, fissures), toxic megacolon, and colonic perforation.

Potential Treatment Complications

Neurologic deterioration may occur from inadequate spinal immobilization or as a complication of surgical instrumentation. Other surgical complications include dural tears with cerebrospinal fluid leaks, infections at the surgical site, pseudarthrosis (which may cause progressive deformity), and chronic pain.

Because people with SCI are often prescribed multiple medications (e.g., to treat pain, spasticity, and bladder or bowel dysfunction), medication-related side effects and complications are common. Complications of urethral catheterization include urethral trauma, erosions, strictures, urinary infections, and epididymitis [20]. Chronic indwelling catheters increase the risk of stones and squamous cell carcinoma of the bladder.