CHAPTER 155

Spinal Cord Injury (Cervical)

Definition

Cervical spinal cord injury (SCI) results in tetraplegia. The term tetraplegia (preferred to quadriplegia) refers to an impairment or loss of motor or sensory function in the cervical segments of the spinal cord due to damage of neural elements within the spinal canal [1]. The result is impairment of function in the arms as well as in the trunk, legs, and pelvic organs. Impairment of sensorimotor involvement outside the spinal canal, such as brachial plexus lesions or injury to peripheral nerves, should not be referred to as tetraplegia.

In a complete cervical SCI, sensory or motor function is absent in the lowest sacral segments S4-S5 (i.e., no anal sensation or voluntary anal contraction is present). If sensory or motor function is partially preserved below the neurologic level and includes the lowest sacral segments, the injury is defined as incomplete [1,2]. The American Spinal Injury Association Impairment Scale (AIS) is used in grading the degree of impairment (Table 155.1). Central cord syndrome is an incomplete SCI syndrome that applies almost exclusively to cervical SCI. It is characterized by greater weakness in the upper limbs than in the lower limbs and sacral sensory sparing [1].

Table 155.1

American Spinal Injury Association Impairment Scale

| Grade | Category | Description |

| A | Complete | No sensory or motor function is preserved in the sacral segments S4-S5. |

| B | Sensory incomplete | Sensory but no motor function is preserved below the neurologic level including the sacral segments S4-S5. |

| C | Motor incomplete* | Motor function is preserved below the neurologic level, and more than half of key muscles below the neurologic level have a muscle grade less than 3. |

| D | Motor incomplete* | Motor function is preserved below the neurologic level, and at least half of key muscles below the neurologic level have a muscle grade 3 or more. |

| E | Normal | Sensory function and motor function are normal; the patient may have abnormalities in reflex examination. |

* There must be some sparing of sensory or motor function in S4-S5 segments to be classified as motor incomplete.

SCI primarily affects young men. However, the average age at injury has increased from 28.7 years in the 1970s to 41.0 years since 2005, and the proportion of new SCI in adults older than 60 years has increased from 4.7% to 13.2% in the same time period in the national Spinal Cord Injury Model Systems database [3]. Males account for about 80% of injuries. The most common cause is motor vehicle accidents, followed by falls, violence (primarily gunshot wounds), and recreational sporting activities [2,3]. The proportion of injuries due to falls has increased over time. Cervical injuries occur more frequently than thoracic and lumbar injuries and accounted for 56.6% of the SCI database between 2005 and 2008. Since 2005, the most frequent neurologic category at discharge reported to the database is incomplete tetraplegia (40.8% of all SCI).

Symptoms

Primary symptoms of cervical SCI are related to muscle paralysis, sensory impairment, and autonomic impairment (including bladder, bowel, and sexual dysfunction). The patient can present in the outpatient setting with a multitude of secondary conditions [4] and associated problems. Symptoms may be vague and nonspecific. For example, urinary tract infections may be manifested not with classic symptoms of urgency and dysuria but with increased spasticity, increased frequency of spontaneous voiding, and lethargy [5]. The patient with pneumonia may present with fever, shortness of breath, or increasing anxiety. Headache may be indicative of autonomic dysreflexia and may be the primary or only presentation of a variety of pathologic processes ranging from bladder distention, urinary infection, constipation, or ingrown toenail to myocardial infarction or acute abdominal emergencies [6]. Table 155.2 lists common presenting symptoms of autonomic dysreflexia and underlying causes.

Table 155.2

Etiology of Common Symptoms in Spinal Cord Injury

| Symptom | Possible Cause |

| Fever | Infectious Urinary tract infection Pneumonia Infected pressure ulcer, cellulitis, osteomyelitis Intra-abdominal or pelvic infection Hot environment (due to poikilothermia) Deep venous thrombosis Heterotopic ossification Pathologic limb fracture Drug fever (e.g., from antibiotics or anticonvulsant pain medications) |

| Fatigue | Nonspecific, but could be the only symptom of serious illness Infection Respiratory or cardiac failure Side effect of medications Depression (inquire about associated dysphoric symptoms) |

| Daytime drowsiness | Side effect of medications (e.g., narcotics, antispasticity agents) Nocturnal sleep apnea Ventilatory failure with carbon dioxide retention Depression |

| Shortness of breath | Pneumonia Abdominal distention (e.g., postprandial, obstipation) Pulmonary embolus Ventilatory impairment (can be postural with sitting up if borderline) Cardiac causes |

| Diarrhea | Altered bowel management schedule Clostridium difficile infection Spurious diarrhea with bowel impaction Side effect of medications (antibiotic, excess laxative or stool softener) |

| Rectal bleeding | Hemorrhoids Trauma from bowel care Colorectal cancer |

| Hematuria | Urinary tract infection Urinary stones Traumatic bladder catheterization Bladder cancer |

| Headache | Autonomic dysreflexia; may be associated with any noxious stimulus below injury level Consider other causes in absence of increased blood pressure |

| Increased spasticity | Urine infection Pressure ulcer Bowel impaction Any noxious stimulus Syringomyelia |

| Pain | Multiple nociceptive and neuropathic causes (see Table 155.3) |

| Unilateral leg swelling | Osteoporotic fracture of the lower extremity Deep venous thrombosis Heterotopic ossification Cellulitis Hematoma Invasive pelvic cancer |

| New weakness or numbness | Syringomyelia Entrapment neuropathy (median at wrist, ulnar at elbow) |

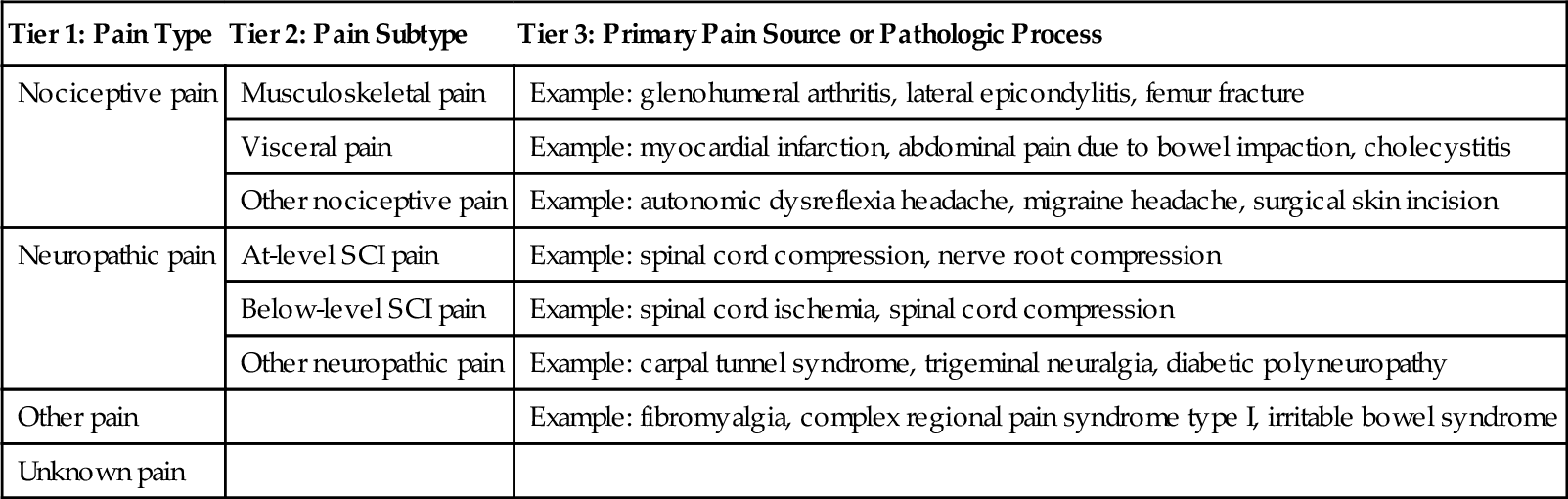

Because symptoms can reflect a variety of underlying conditions, these need to be evaluated carefully. For example, pain in cervical SCI may be multifactorial and needs to be further assessed by characteristics reported in the history, including quality, location, onset, timing, relieving and exacerbating factors, and associated symptoms. Various SCI pain classification systems have been described. The International Spinal Cord Injury Pain classification (Table 155.3) organizes SCI pain into three tiers: tier 1 classifies pain type as nociceptive, neuropathic, other, and unknown; tier 2 includes various subtypes for neuropathic and nociceptive pain; and tier 3 is used to specify the primary pain source or pathologic process [7].

Physical Examination

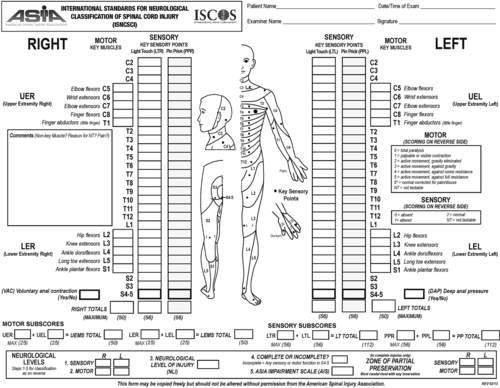

The neurologic examination is conducted by systematic examination of the dermatomes and myotomes (Tables 155.4 and 155.5) in accordance with the International Standards for Neurological and Functional Classification of Spinal Cord Injury, published by the American Spinal Injury Association [1]. Depending on the presentation, specific elements of the physical examination of various body systems that are relevant in evaluation of SCI-related conditions may include the following.

Table 155.4

Key Sensory Points for Cervical Spinal Segments

| Level | Key Sensory Point |

| C2 | Occipital protuberance |

| C3 | Supraclavicular fossa |

| C4 | Top of the acromioclavicular joint |

| C5 | Lateral side of the antecubital fossa |

| C6 | Thumb, dorsal surface, proximal phalanx |

| C7 | Middle finger, dorsal surface, proximal phalanx |

| C8 | Little finger, dorsal surface, proximal phalanx |

| T1 | Medial side of antecubital fossa |

Table 155.5

Key Muscle Groups for Cervical Myotomes*

| Level | Muscle Group | Positions for Testing Key Muscles for Grades 4 and 5 |

| C5 | Elbow flexors (biceps, brachialis) | Elbow flexed at 90°, arm at patient’s side, forearm supinated |

| C6 | Wrist extensors (extensor carpi radialis longus and brevis) | Wrist in full extension |

| C7 | Elbow extensors (triceps) | Shoulder in neutral rotation, adducted, and in 90° of flexion, with elbow in 45° of flexion |

| C8 | Finger flexors (flexor digitorum profundus) to the middle finger | Full-flexed position of the distal phalanx with the proximal finger joints stabilized in extended position |

| T1 | Small finger abductors (abductor digiti minimi) | Full-abducted position of the fifth digit of the hand |

* For those myotomes that are not clinically testable by manual muscle examination (e.g., C1 to C4), the motor level is presumed to be the same as the sensory level.

Neurologic

• Determine the level and completeness of the injury (Fig. 155.1). Conduct the examination in the supine position.

• Sensory examination for pinprick and light touch sensation in key points bilaterally (see Table 155.4)

• Motor examination for strength in key muscle groups bilaterally (see Table 155.5)

• Neurologic rectal examination (voluntary anal contraction, deep anal sensation)

• Determine completeness of injury and AIS grade (see Table 155.1). If the AIS grade is A, determine the zone of partial preservation.

• Additional elements of the neurologic examination include

• Position and deep pressure sensation, testing of additional muscles

• Muscle tone and spasticity

• Muscle stretch reflexes, bulbocavernosus reflex, plantar reflex

Respiratory

• Assess respiratory effort, including effect of posture (e.g., sitting versus supine).

• Check for paradoxical respiration and chest expansion.

• Auscultate to assess for decreased breath sounds, rales, and wheeze.

Cardiac

• Low baseline blood pressure is often a “normal” finding in SCI.

• Look for orthostatic symptoms or excess fall in blood pressure with sitting or upright position.

• High blood pressure may indicate autonomic dysreflexia (Table 155.6).

• Examination of peripheral pulses may be especially important for identification of peripheral vascular disease in the absence of claudication and pain symptoms.

Abdomen

• Examine for abdominal distention; examine bowel sounds for evidence of ileus.

• Perform anorectal examination for hemorrhoids and fissures.

Spine

• Identify spinal deformity and tenderness.

• Observe spinal precautions if the examination is being conducted in the acute or postoperative state.

Extremities

• Examine for range of motion, contractures, and swelling.

• Identify nociceptive sources of pain; palpate for tenderness.

• Differentiate effects of SCI (pedal edema, cool extremities) from additional pathologic processes.

Skin

• Examine bone prominences for erythema or skin breakdown.

• Describe any pressure ulcers: location, appearance, size, stage, exudate, odor, necrosis, undermining, sinus tracks; evidence of healing in form of granulation and epithelialization; wound margins and surrounding tissues [8].

Functional Limitations

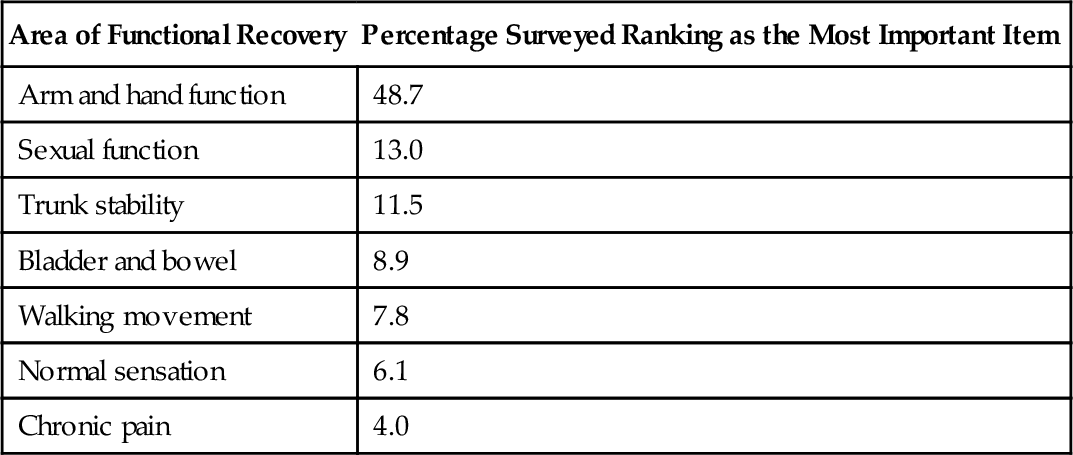

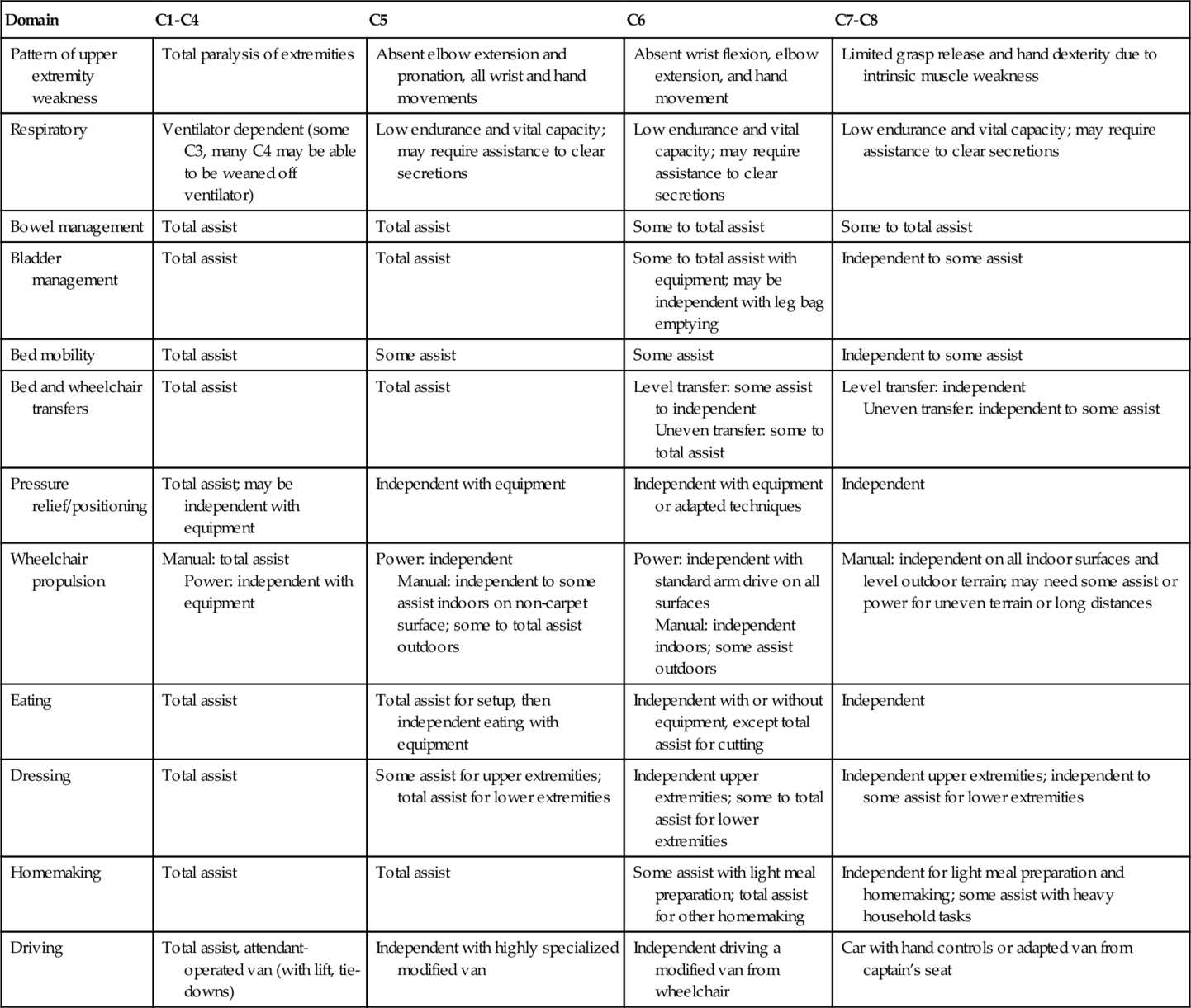

Tetraplegia is associated with several functional limitations based on the level and completeness of injury [9]. Additional factors, such as age, comorbid conditions, pain, spasticity, body habitus, and psychosocial and environmental factors, can affect function after cervical SCI. A survey of individuals with tetraplegia conducted to rank seven functions in order of importance to their quality of life revealed that the greatest percentage ranked recovery of arm and hand function as their highest priority [10] (Table 155.7).

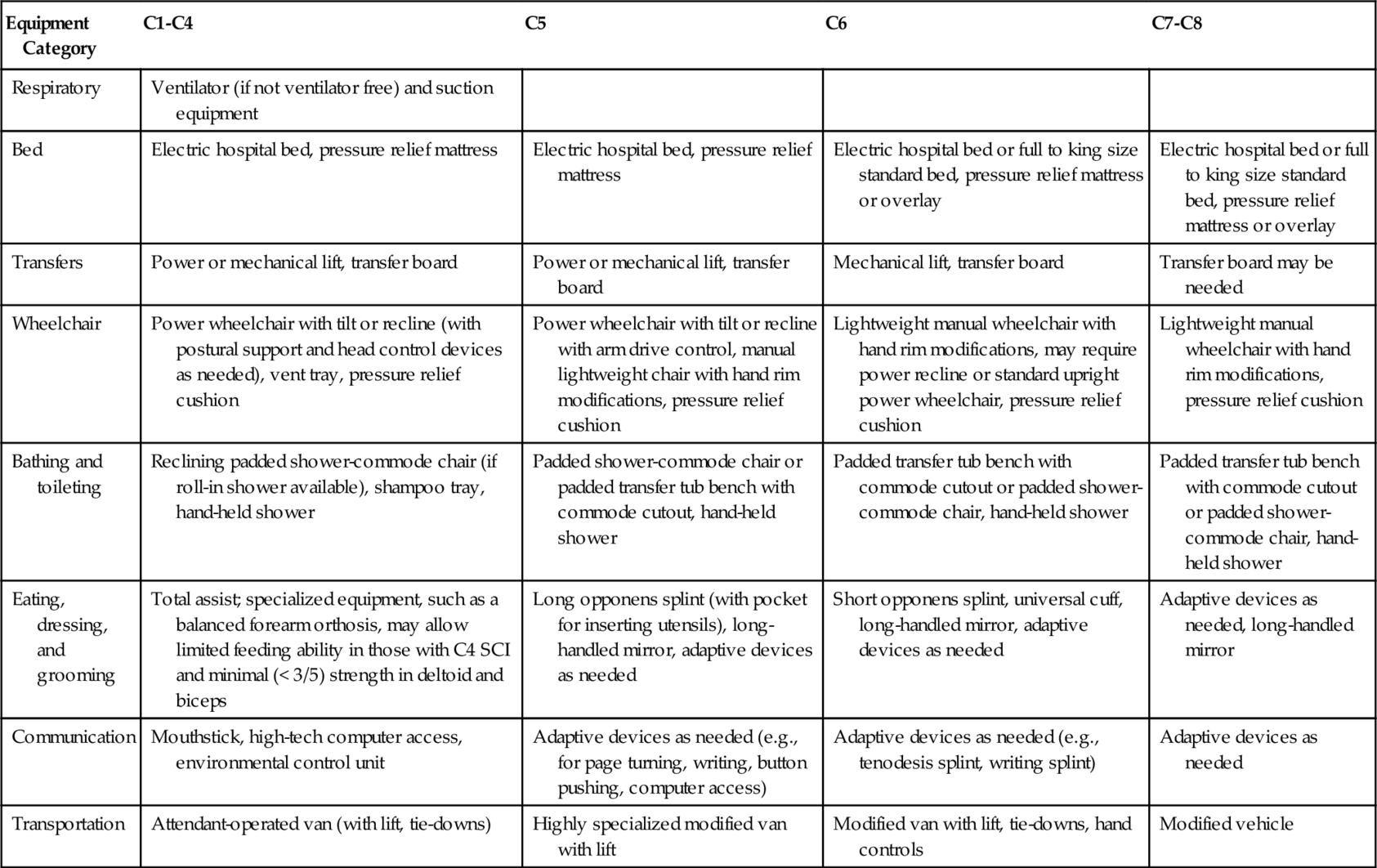

The Consortium for Spinal Cord Medicine has developed clinical practice guidelines on outcomes after SCI with expected functional outcomes for each level of injury in a number of domains [9,11]. Expected functional outcomes and equipment needs for each level of complete cervical SCI are summarized in Tables 155.8 and 155.9.

Table 155.8

Pattern of Weakness and Functional Outcomes after Cervical Spinal Cord Injury*

| Domain | C1-C4 | C5 | C6 | C7-C8 |

| Pattern of upper extremity weakness | Total paralysis of extremities | Absent elbow extension and pronation, all wrist and hand movements | Absent wrist flexion, elbow extension, and hand movement | Limited grasp release and hand dexterity due to intrinsic muscle weakness |

| Respiratory | Ventilator dependent (some C3, many C4 may be able to be weaned off ventilator) | Low endurance and vital capacity; may require assistance to clear secretions | Low endurance and vital capacity; may require assistance to clear secretions | Low endurance and vital capacity; may require assistance to clear secretions |

| Bowel management | Total assist | Total assist | Some to total assist | Some to total assist |

| Bladder management | Total assist | Total assist | Some to total assist with equipment; may be independent with leg bag emptying | Independent to some assist |

| Bed mobility | Total assist | Some assist | Some assist | Independent to some assist |

| Bed and wheelchair transfers | Total assist | Total assist | Level transfer: some assist to independent Uneven transfer: some to total assist |

Level transfer: independent Uneven transfer: independent to some assist |

| Pressure relief/positioning | Total assist; may be independent with equipment | Independent with equipment | Independent with equipment or adapted techniques | Independent |

| Wheelchair propulsion | Manual: total assist Power: independent with equipment |

Power: independent Manual: independent to some assist indoors on non-carpet surface; some to total assist outdoors |

Power: independent with standard arm drive on all surfaces Manual: independent indoors; some assist outdoors |

Manual: independent on all indoor surfaces and level outdoor terrain; may need some assist or power for uneven terrain or long distances |

| Eating | Total assist | Total assist for setup, then independent eating with equipment | Independent with or without equipment, except total assist for cutting | Independent |

| Dressing | Total assist | Some assist for upper extremities; total assist for lower extremities | Independent upper extremities; some to total assist for lower extremities | Independent upper extremities; independent to some assist for lower extremities |

| Homemaking | Total assist | Total assist | Some assist with light meal preparation; total assist for other homemaking | Independent for light meal preparation and homemaking; some assist with heavy household tasks |

| Driving | Total assist, attendant-operated van (with lift, tie-downs) | Independent with highly specialized modified van | Independent driving a modified van from wheelchair | Car with hand controls or adapted van from captain’s seat |

* These outcomes pertain to expected function after motor complete SCI; functional outcomes after incomplete SCI vary on the basis of the extent of motor preservation.

Diagnostic Studies

Spinal Imaging

Radiologic studies are performed to identify and to characterize the site of the pathologic change. Magnetic resonance imaging is especially helpful because of its ability to visualize the soft tissues, including ligamentous structures, intravertebral discs, epidural or subdural hematomas, and hemorrhage or edema in the spinal cord. Magnetic resonance imaging with gadolinium is helpful in diagnosis of post-traumatic syringomyelia.

Electrodiagnostic Testing

Electromyography and nerve conduction studies may be helpful in distinguishing lesions of the peripheral nerves or brachial plexus from those of the spinal cord when patients present with neurologic worsening [12].

Urologic Studies

Urodynamic studies assess neurogenic bladder and sphincter dysfunction. Tests to evaluate upper urinary tracts may be indicated on a periodic basis, but there currently is no uniform consensus on the type or frequency of these tests [4]. Periodic cystoscopy may be indicated in those with chronic indwelling urinary catheters because of increased risk of bladder cancer [13].

Pulmonary Function

Patients who are at high risk for pulmonary complications, such as those with high tetraplegia or with concomitant chronic obstructive airway disease, may require yearly measurements of forced vital capacity and repeated evaluations when new symptoms arise [14]. Chest radiographs will show evidence of pneumonia or atelectasis. Sputum culture and Gram stain will identify the involved pathogens and help guide antibiotic therapy.

Musculoskeletal Imaging

Radiographic evaluation may be needed in case of suspected fracture or to evaluate pain. Heterotopic ossification may be assessed with a bone scan in addition to plain radiographs [12]. If a pressure ulcer appears to involve the bone, magnetic resonance imaging or bone scan may be helpful to evaluate for osteomyelitis [5].

Treatment

Initial

Initial management includes adequate spinal immobilization and prevention of secondary injury. Physiatric consultation and intervention in an acute setting should address range of motion, positioning, bowel and bladder management programs, clearance of respiratory secretions, ventilatory management, consideration of venous thromboembolic prophylaxis, prevention of pressure ulcers, input about functional implications of options for surgery and spinal orthosis, and education of the patient and family [15].

Rehabilitation

Information about potential for motor recovery can be used to set functional goals and to plan for equipment needs (as described in Tables 155.8 and 155.9), keeping in mind that individual factors and coexisting conditions may affect achievable goals [9]. Important elements of rehabilitation include an interdisciplinary approach, establishment of an individualized rehabilitation program with consideration of unique barriers and facilitators, and inclusion of the patient as an active participant in establishment of goals [11]. Specialized equipment needs, based on the level of injury, are summarized in Table 155.9.

In addition to the post-acute rehabilitation that follows the injury, lifelong rehabilitation interventions are often indicated to address changes in neurologic status, new goals, changes in living situation, functional decline associated with medical complications and comorbidities, and aging [16]. Home modifications should be instituted to ensure accessibility [11].

Ongoing Management and Health Maintenance

There is general consensus that comprehensive preventive health evaluations for individuals with SCI are important [4], although uniform agreement about optimal frequency and specific elements is lacking. Because all body systems are potentially affected by cervical SCI, long-term management needs to be comprehensive as summarized here.

Respiratory

Respiratory infections should be promptly identified and treated [17]. Measures such as smoking cessation and pneumonia and annual influenza vaccinations are important for reducing respiratory problems [4]. Manually assisted cough methods can be taught to patients and caregivers. It is important to recognize and to address worsening ventilatory function that may occur with aging or after other complications.

Cardiovascular

Autonomic dysreflexia is a life-threatening emergency, and persons with tetraplegia can be at lifelong risk. Prompt identification and management are critical. The Consortium for Spinal Cord Medicine has published clinical practice guidelines for the acute management of autonomic dysreflexia [6]. If the patient has signs and symptoms of dysreflexia (see Table 155.6), the blood pressure is elevated, and the individual is supine, immediately sit the person up. Loosen any clothing or constrictive devices. Monitor the blood pressure and pulse frequently. Quickly survey for instigating causes, beginning with the urinary system. If an indwelling urinary catheter is not in place, catheterize the individual. Before the catheter is inserted, instill lidocaine jelly (if it is readily available) into the urethra. If the individual has an indwelling urinary catheter, check the system along its entire length for kinks, folds, constrictions, or obstructions and for correct placement of the indwelling catheter. If a problem is found, correct it immediately. Avoid manual compression of or tapping on the bladder. If the catheter is not draining and the blood pressure remains elevated, remove and replace the catheter. If the catheter cannot be replaced, consult a urologist. If acute symptoms of autonomic dysreflexia persist, including a sustained elevated blood pressure, suspect fecal impaction. If the elevated blood pressure is at or above 150 mm Hg systolic, consider pharmacologic management to reduce the systolic blood pressure without causing hypotension before checking for fecal impaction. Use an antihypertensive agent with rapid onset and short duration (e.g., nifedipine bite and swallow, 2% nitroglycerin ointment, or prazosin) while the causes of autonomic dysreflexia are being investigated, and monitor the individual for symptomatic hypotension. If fecal impaction is suspected, check the rectum for stool. If the precipitating cause of autonomic dysreflexia is not yet determined, check for other less frequent causes. Monitor the individual’s symptoms and blood pressure for at least 2 hours after resolution of the autonomic dysreflexia episode to make sure that it does not recur. If there is poor response to the treatment specified or if the cause of the dysreflexia has not been identified, strongly consider admitting the individual to the hospital to be monitored, to maintain pharmacologic control of the blood pressure, and to investigate other causes of the dysreflexia. Document the episode in the individual’s medical record. Once the individual with SCI has been stabilized, review the precipitating causes with the individual and caregivers and provide education as necessary [6]. Individuals with tetraplegia and their caregivers should be able to recognize and to treat autonomic dysreflexia and be taught to seek emergency treatment if it is not promptly resolved.

Treatment of symptomatic orthostatic hypotension [11] addresses any exacerbating causes (e.g., medications, dehydration, or sepsis). Nonpharmacologic measures include postural challenges, abdominal binder, compression stockings, and increased salt intake. Pharmacologic treatment is administered if it is needed (e.g., with ephedrine, fludrocortisone, or midodrine).

Primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease includes smoking cessation, diet and weight control, lipid management, screening for and treatment of hypertension and glucose intolerance or diabetes, and individualized exercise program [18]. For evaluation of coronary artery disease, a modified or pharmacologic stress test is often needed in these individuals, and if a cardiac rehabilitation program is required, it can be adapted for wheelchair users.

Genitourinary

The goals of bladder management (Table 155.10) are to ensure low pressure and complete voiding, to minimize urinary tract complications, to preserve upper urinary tracts, and to be compatible with the individual’s lifestyle [13]. Anticholinergic medications (e.g., oxybutynin, tolterodine) may be indicated for detrusor hyperreflexia and α-adrenergic blockers (prazosin, terazosin, tamsulosin) for detrusor-sphincter dyssynergia. Urinary infections should be identified and treated promptly, but antibiotics are generally not recommended for asymptomatic bacteriuria [5]. There is little role for prophylactic antibiotics, except before urologic procedures.

Table 155.10

Nonsurgical Options for Management of the Neurogenic Bladder in Spinal Cord Injury

| Bladder Management | Indications |

| Intermittent catheterization | Often the first choice, if feasible Need sufficient hand skills or willing caregiver Must be willing and able to follow catheterization time schedule |

| Indwelling catheterization (urethral or suprapubic) | Consider for poor hand skills and lack of caregiver assistance Not able or willing to follow intermittent catheterization schedule High fluid intake Lack of success with less invasive measures Temporary management of vesicoureteral reflux Choose suprapubic with epididymo-orchitis, prostatitis |

| Credé and Valsalva | Generally avoided in cervical SCI (unless the patient had sphincterotomy) |

| Reflex voiding | Hand skills or willing caregiver to put on condom catheter, empty leg bag Confirmed small postvoid residual volumes, low voiding pressure Able to maintain condom catheter in place Need to also decrease detrusor-sphincter dyssynergia, if present (e.g., with alpha blocker, botulinum toxin injection, stent, sphincterotomy) Not an option for female patients |

Counseling and education are key elements of managing sexual dysfunction [19]. Phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors (sildenafil, tadalafil, vardenafil) may be used to treat erectile impairment, although care needs to be taken to avoid simultaneous use of nitrate-based medications to treat autonomic dysreflexia, which could result in severe hypotension [4]. Other options include intracavernosal injections, devices, and implants. Advances in electroejaculation and fertility care have increased the fertility success rate for men with SCI. Female fertility is not affected once menses return, which typically occurs within 1 year of injury. Pregnancy and delivery in women with SCI carries risks, including autonomic dysreflexia, and close follow-up is recommended [4,19].

Gastrointestinal

The goals of bowel management are to facilitate predictable and effective elimination and to minimize bowel incontinence [20]. A scheduled individualized bowel program should be established, which typically includes reflex stimulation maneuvers, laxatives (stool softeners, stimulants), dietary interventions, and adequate fiber intake. Laxatives and enemas should be kept to a minimum. One should beware of fecal impaction presenting as spurious diarrhea and pay due attention to new bowel symptoms.

Skin

Education of the patient, regular pressure relief practices, and prescription of pressure-reducing support surfaces are vital for prevention of pressure ulcers [8]. Daily comprehensive skin inspections should be carried out by the patient or caregiver, with particular attention to vulnerable insensate areas (e.g., sacrum-coccyx, ischii, trochanters, and heels). Adequate nutritional intake is important. Management of pressure ulcers is discussed further in Chapter 148.

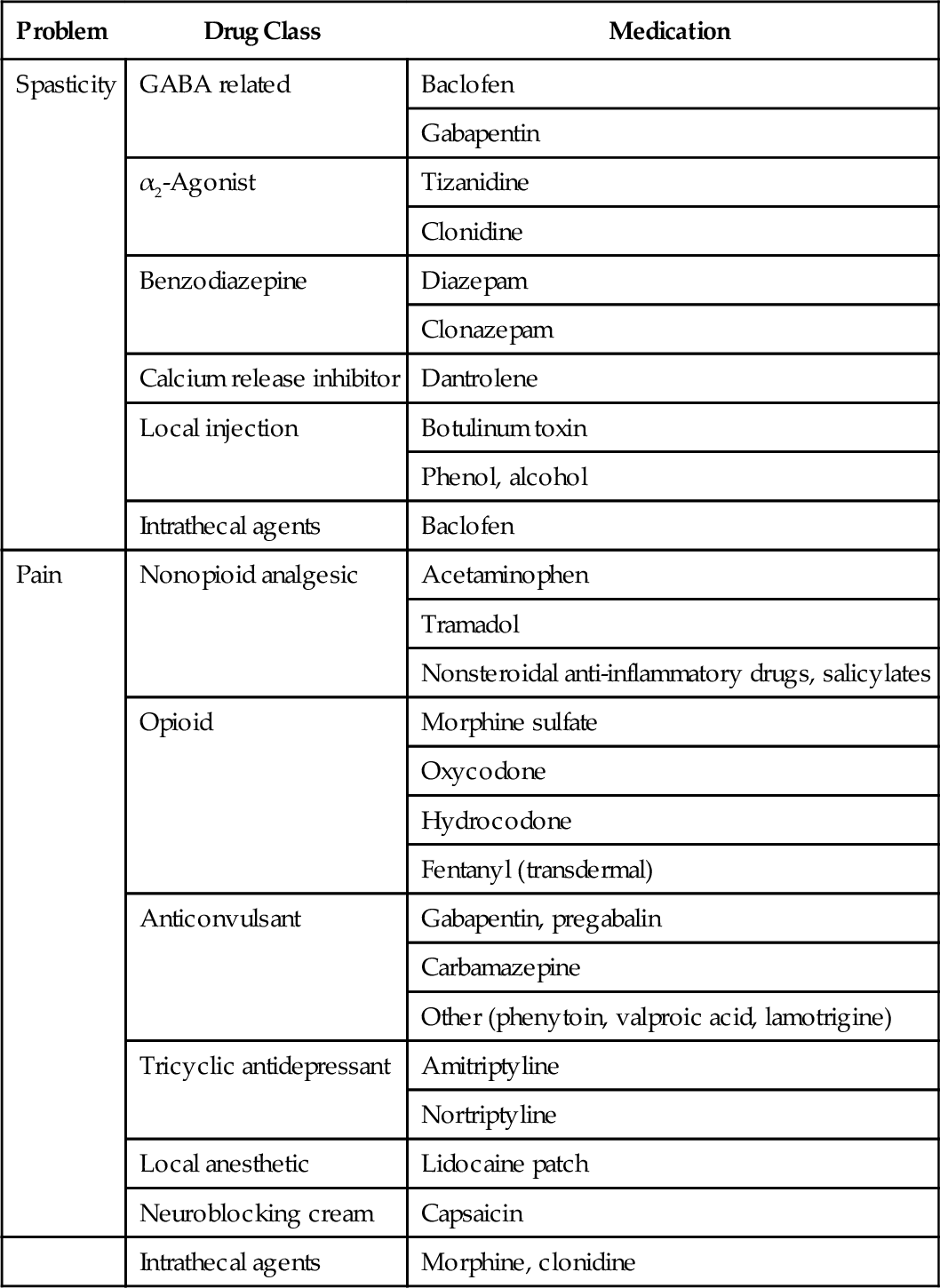

Neurologic

If spasticity is painful or continues to interfere with function after institution of a stretching and positioning program and treatment of any exacerbating factors, medications are often indicated [21]. Table 155.11 lists commonly used medications. Chapter 153 provides additional discussion about spasticity. Selective tightening (e.g., wrist extensors for tenodesis or back extensors for sitting balance) may be important for function in tetraplegia. Neurologic worsening (e.g., due to focal neuropathy, syringomyelia) should be investigated and addressed appropriately [12].

Table 155.11

Medications Commonly Used for Spasticity and Pain in Spinal Cord Injury*

| Problem | Drug Class | Medication |

| Spasticity | GABA related | Baclofen |

| Gabapentin | ||

| α2-Agonist | Tizanidine | |

| Clonidine | ||

| Benzodiazepine | Diazepam | |

| Clonazepam | ||

| Calcium release inhibitor | Dantrolene | |

| Local injection | Botulinum toxin | |

| Phenol, alcohol | ||

| Intrathecal agents | Baclofen | |

| Pain | Nonopioid analgesic | Acetaminophen |

| Tramadol | ||

| Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, salicylates | ||

| Opioid | Morphine sulfate | |

| Oxycodone | ||

| Hydrocodone | ||

| Fentanyl (transdermal) | ||

| Anticonvulsant | Gabapentin, pregabalin | |

| Carbamazepine | ||

| Other (phenytoin, valproic acid, lamotrigine) | ||

| Tricyclic antidepressant | Amitriptyline | |

| Nortriptyline | ||

| Local anesthetic | Lidocaine patch | |

| Neuroblocking cream | Capsaicin | |

| Intrathecal agents | Morphine, clonidine |

* The list is not meant to be exhaustive but includes examples of commonly used medications.

Musculoskeletal

Measures for upper extremity preservation after SCI should be instituted early and followed lifelong. These include optimization of equipment and wheelchair to minimize upper extremity stresses, activity modification to minimize repetitive or excessive upper extremity forces during daily activities and transfers, and individualized exercise program incorporating appropriate flexibility and strengthening components [22].

It is important to recognize and to address contributing factors to pain, which is often multifactorial [7] (see Table 155.3). Pain medications (see Table 155.11) often do not provide complete or optimal relief [21].

Heterotopic ossification is treated with etidronate sodium, nonsteroidals, and occasionally surgical resection, especially if it is interfering with function or comfort [11]. Pathologic fractures should be recognized and treated with padded splints or bivalved circular casts, monitoring of skin integrity, and often only a limited role for surgical treatment [12]. The role for pharmacologic treatment of osteoporosis in SCI is still evolving. Fall prevention (education, wheelchair lap belts) is important to prevent injuries.

Psychosocial

It is important to address environmental barriers (physical and attitudinal), to promote self- efficacy, and to optimize participation and community integration in response to changes in the living situation and social support, functional decline, and aging. Depression should be identified and treated adequately, and substance abuse prevention and treatment programs should be offered [23].

Procedures

Pressure Ulcers

Sharp débridement of pressure ulcers may be done at the bedside to remove necrotic tissue, although if it is extensive, débridement may need to be done in the operating room.

Spasticity

Motor point or nerve blocks with phenol or alcohol may be helpful in treating localized spasticity that interferes with positioning, mobility, or hygiene. Intramuscular injections of botulinum toxin are another option.

Pain

Shoulder pain due to subacromial bursitis may be temporarily responsive to local corticosteroid injections, as is the discomfort from carpal tunnel syndrome [22].

Surgery

Spine Surgery

When cervical spine injury is accompanied by mechanical instability, pain, deformity, or progressive neural impairment, surgical decompression and segmental instrumentation may be indicated for reconstruction of spinal alignment, stability, and early mobilization [12,15].

Pressure Ulcers

Plastic surgery may be indicated for deep pressure ulcers. This includes excision of the ulcer and surrounding scar and muscle and musculocutaneous flap closure [22].

Spasticity

If spasticity is not controlled with maximum dosages of oral medications, or if a patient is unable to tolerate the medications, the placement of an intrathecal baclofen pump may be considered.

Motor Function

Reconstructive surgery of the upper extremity with tendon transfers may improve motor function by one level, typically in those with a neurologic level at C5, C6, or C7. Depending on the level of injury, restoration of wrist extension, elbow extension, and key grip strength or improvement of active grasp and hand control may be an appropriate goal [24].

Functional electrical stimulation has been used in SCI to improve motor function, including upper limb control, standing, and walking, as well as for electrophrenic respiration for ventilator-free breathing [11].

Bladder Dysfunction

Surgical treatment of urolithiasis includes cystoscopic removal of bladder stones, lithotripsy, and percutaneous nephrolithotomy for larger renal stones. Endourethral stents or transurethral sphincterotomy may be considered in individuals with detrusor-sphincter dyssynergia [13]. Electrical stimulation and posterior sacral rhizotomy may be considered for individuals who have problems with catheterization, have good bladder contractions, have no extensive bladder fibrosis, and are willing to lose reflex erections [13]. Bladder augmentation may be indicated for intractable bladder contractions with incontinence and in those at high risk for upper tract deterioration. Urinary diversion may be an appropriate option for unsalvageable bladders secondary to urethral fistula and in individuals with bladder cancer requiring cystectomy [13].

Bowel Dysfunction

Patients with neurogenic bowel who have significant difficulty or complications with typical bowel care may have improved quality of life after colostomy. Careful selection of patients and individualization are required in consideration of this surgery [20].

Upper Extremity Pain

Surgery may occasionally be considered for chronic upper extremity overuse-related symptoms that are unresponsive to medical and rehabilitative treatment (e.g., for carpal tunnel syndrome or rotator cuff disease). Outcomes are often poor if upper extremity overuse continues [22].

Post-traumatic Syringomyelia

Surgical placement of shunts may be indicated for post-traumatic syringomyelia associated with intractable pain or progressive neurologic decline.

Potential Disease Complications

Cervical SCI is associated with multiple complications that can involve every body system.

Respiratory

Respiratory problems include atelectasis, mucous plugs, and pneumonia secondary to impaired cough and retention of secretions; ventilatory failure with high tetraplegia; and sleep disordered breathing [17].

Cardiovascular

Patients with cervical SCI are prone to multiple cardiovascular complications throughout life [18]. Autonomic dysreflexia may occur in SCI above the T6 neurologic level and can be precipitated in response to any noxious stimulus below the level of injury. Symptomatic orthostatic hypotension often resolves after the first few months but may be persistent in some cases. Although venous thromboembolism risk is reduced after the initial months, it can increase even in chronic SCI in the setting of prolonged immobilization associated with medical illness or in the postsurgical state. Cardiovascular fitness is reduced and cardiovascular risk factors can be adversely affected (e.g., reduced high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, increased body fat and insulin resistance, decreased physical activity). Diagnosis of cardiovascular disease may be delayed because of confusing or absent symptoms and signs [18].

Genitourinary

Neurogenic bladder is associated with loss of voluntary control, detrusor-sphincter dyssynergia, and incomplete bladder emptying. Complications include urinary tract infection, bladder and kidney stones, vesicoureteral reflux, and hydronephrosis with renal impairment. Bladder cancer risk is increased with chronic indwelling catheter, especially in smokers [13]. Erectile and ejaculatory dysfunction occurs, and sperm quality may be impaired [4,19].

Gastrointestinal

There is loss of voluntary bowel control, anorectal dyssynergia, and reduced rectal expulsive force [20]. Fecal impaction may occur. Anorectal problems include hemorrhoids, fissures, proctitis, and prolapse. Gallstone risk is increased. Gastroesophageal reflux is common. False-positive results of examination for fecal occult blood may complicate colorectal cancer screening.

Skin

Pressure ulcers are common and may increase with duration of injury. Previous occurrence of a pressure ulcer is an important predictor of future pressure ulcers [8].

Metabolic and Endocrine

Hyponatremia may be a persistent problem in some patients. Carbohydrate and lipid metabolism is affected, and there may be glucose intolerance associated with relative insulin resistance [16]. A reduction in bone mineral density with secondary osteoporosis is common in chronic SCI and affects both the upper and lower extremities in those with tetraplegia.

Neurologic

Neuropathic pain can be persistent and have a negative impact on quality of life. Entrapment neuropathies (median nerve at wrist, ulnar nerve at elbow) and post-traumatic syringomyelia can result in neurologic deterioration [12].

Musculoskeletal

Overuse syndromes include shoulder pain and rotator cuff problems [12,22]. Contractures may occur without due attention to range of motion and positioning. Individuals with C5 level of injury are especially prone to elbow flexion and forearm supination contractures because of unopposed biceps activity. Heterotopic ossification, which is the development of ectopic bone within the soft tissues surrounding peripheral joints, occurs in SCI most commonly around the hip, followed by the knees, elbows, and shoulders [12]. It is further discussed in Chapter 130. Pathologic fractures may occur even with trivial injury because of severe osteoporosis [12].

Psychosocial

SCI can increase the potential for stress, isolation, and depression [23]. Alcohol and substance abuse risk seems to be increased.

Potential Treatment Complications

Spinal pain at the surgical site may result from loosening, infection, or broken hardware. Instability or neurologic deterioration may be due to inadequate spinal immobilization. Surgical shunts can become blocked or infected, and intrathecal pumps or catheters may malfunction.

Complications of urethral catheterization include urethral trauma, erosions, strictures, urinary infections, and epididymitis [13]. Chronic indwelling catheters increase the risk of stones and squamous cell carcinoma of the bladder. Complications may occur with surgical procedures for SCI-related problems, such as neurogenic bladder. For example, transurethral sphincterectomy may be associated with significant intraoperative and perioperative bleeding and erectile and ejaculatory dysfunction. Posterior sacral rhizotomy done in conjunction with electrical stimulation of the bladder may result in loss of reflex erection and ejaculation and reduction of reflex defecation. Urinary diversion procedures may be followed by intestinal or urinary leak, infection, ureteroileal stricture, stomal stenosis, and intestinal obstruction due to adhesions [13].

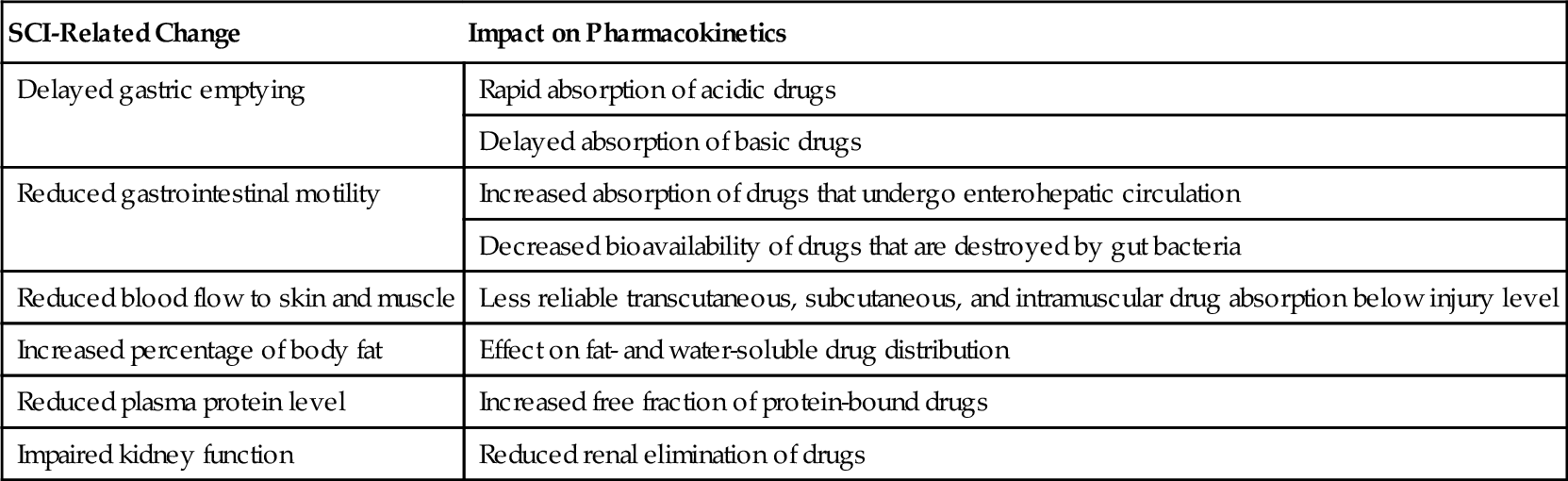

Because people with SCI are often prescribed multiple medications, drug-related side effects and complications are common. Cervical SCI can result in altered pharmacokinetics [25] in multiple ways (Table 155.12), which further increases unpredictability of side effects.