CHAPTER 154

Speech and Language Disorders

Jason H. Kortte, MS, CCC-SLP; Jeffrey B. Palmer, MD

Definitions

A summary of the speech and language disorders described in this chapter is presented in Table 154.1.

Table 154.1

Speech and Language Disorders

| Disorder | Definition |

| Aphasia | Language processing disturbance that can involve the expression of language, the comprehension of language, or both Word finding errors and difficulty in understanding language are classic indicators of aphasia. |

| Dysarthria | Group of motor speech disorders associated with muscle paralysis, weakness, or incoordination Dysarthria often is manifested as slurred speech and does not involve language (receptive or expressive) processes. |

| Apraxia of speech | Motor speech disorder disrupting the motor programming of the volitional movements for speech Individuals struggle to find correct position of articulators (i.e., lips, tongue). It can occur without muscle weakness or impairments in receptive and expressive language. |

| Dysphonia | Faulty or abnormal phonation (voice production) Vocal quality may sound hoarse, harsh, strained, or breathy. |

Aphasia is an acquired, neurogenic language processing impairment that can disrupt the modalities of language, including speaking, listening, reading, and writing. Aphasia is commonly caused by stroke; it occurs in 21% to 38% of cases of acute stroke and is associated with high morbidity, mortality, and financial cost [1]. However, aphasia can result from brain injuries other than stroke, such as tumors and head trauma, and it must be differentiated from motor or sensory dysfunction, psychiatric illness, confusion, or general intellectual impairment [2]. In the United States, there are approximately 100,000 new cases of aphasia per year; the majority are women and 65 years of age or older [3]. Primary progressive aphasia is a term reserved for subtle, insidious progressive language impairments associated with frontal-temporal dementia. In primary progressive aphasia, there is relative preservation of other mental and cognitive functions for at least the first 2 years of the condition [4].

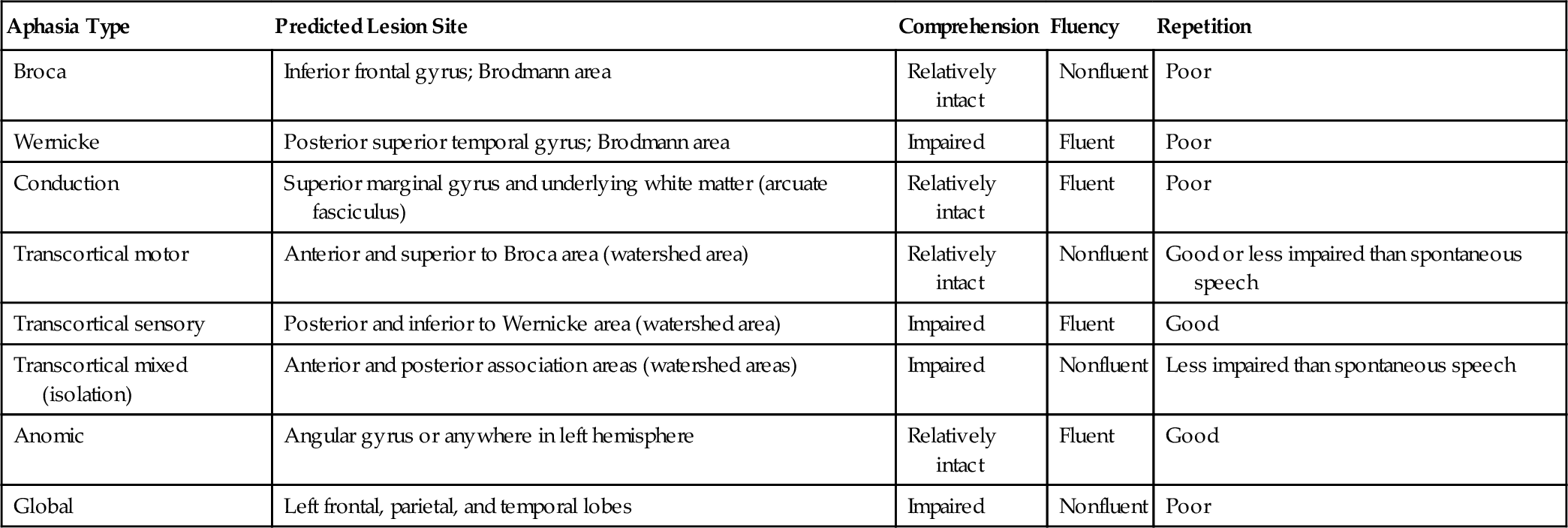

Aphasia is classified into subtypes according to the ability to produce, to understand, and to repeat language [5]. The ability to produce language is assessed in terms of fluency, defined as the rate of speech and the amount of effort in producing speech. Each subtype of aphasia is associated with a specific profile of language capabilities and disabilities (Table 154.2). For example, an individual with Wernicke aphasia produces fluent language, has impaired auditory comprehension, and has poor repetition skills. In contrast, Broca aphasia is characterized by nonfluent language, relatively intact auditory comprehension, and poor repetition skills.

Motor speech disorders, which include dysarthria and apraxia of speech, result from neurologic impairment affecting motor planning, neuromuscular control, or execution of speech [6]. Apraxia of speech results from a disruption in programming of the volitional movements for speech and is characterized by difficulty in orchestrating the movements of the lips, tongue, jaw, soft palate, vocal cords, and respiratory system for the production of speech. It can occur without muscle weakness or impairments in receptive and expressive language. Apraxia of speech is a distinct disorder, although some of its symptoms can co-occur in the presence of dysarthria and aphasia [7].

Dysarthria, a group of motor speech disorders resulting from damage to the central or the peripheral nervous system, affects 10% to 65% of individuals with acquired brain injury, depending on the type, extent, and duration of injury [8]. Dysarthria results from weakness, paralysis, or dyscoordination of the speech muscles that impairs articulation, respiration, resonance, and phonation (voice production). Dysarthria is divided into subtypes according to the speech characteristics and underlying pathophysiologic process. Neurogenic speech disorders should be differentiated from those resulting from structural problems (such as cleft palate or post-laryngectomy status) or psychogenic disorders [6]. The extreme form of dysarthria is anarthria, in which the individual is entirely incapable of producing articulated speech. Individuals with dysarthria often have dysphagia, or impaired swallowing, regardless of the etiology or duration [9]. This is readily understood, considering the overlap of structures and functions used in speaking and swallowing (see Chapter 129).

Dysphonia is faulty or abnormal phonation (voice production). Although prevalence rates are not well established, dysphonia is common in any condition causing abnormal motion of the vocal cords or dyscoordination of breathing and speaking. These include brainstem stroke, Parkinson disease, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, Guillain-Barré syndrome, myasthenia gravis, spastic dysphonia, and multiple sclerosis, among others [6], as well as secondary processes that alter the structure or function of the vocal cords, including vocal abuse (such as excessive talking, screaming, or smoking), trauma (traumatic or prolonged intubation, arytenoid dislocation), status post–laryngeal surgery, and a variety of disorders (laryngeal cancer, reflux laryngitis) [10]. Dysphonia is distinguished from dysarthria in that dysphonia involves only the sound of the voice, whereas dysarthria involves the overall sound of speech, including resonance and articulation.

Symptoms

Individuals with aphasia often complain of difficulty in speaking, reading, writing, or understanding speech. They often report difficulty in finding the word they wish to say and can become frustrated; however, some are unaware of their deficits. Individuals who solely have a motor speech disorder (e.g., dysarthria, dysphonia, or apraxia of speech) have no difficulty in finding the words they wish to say and report no difficulties with reading, writing, or auditory comprehension but complain primarily of difficulty in producing intelligible speech. Aphasia develops most commonly after left hemisphere stroke even in people who are left handed, whereas neglect, visual-spatial impairments, and other cognitive syndromes are more common after right hemisphere strokes [11].

Physical Examination

During the initial history and physical, the physiatrist should attend to speech intelligibility, vocal quality, language content, fluency, and auditory comprehension. Deficits in these areas warrant referral to a certified speech-language pathologist for comprehensive evaluation including standardized testing. In the rehabilitation setting, the Functional Independence Measure is widely used to measure functional abilities including communication [12]. Typical findings are described here for the four main categories of speech and language disorders.

Aphasia

Findings indicative of aphasia vary according to the location and size of the brain lesion (see Table 154.2). One classic sign of aphasia is difficulty in comprehending language (spoken, gestural, or written). Significant impairment can be characterized by difficulty in following simple commands, whereas milder impairments may be obvious only during lengthy or complicated messages. Individuals who have aphasia may also have deficits in verbal expression (producing meaningful verbal output), which may be manifested as a total loss of language, with the production of only jargon (multiple whole-word substitutions) or meaningless sounds. A person with less severe aphasia may be able to express basic wants and needs but have difficulty in expressing complex ideas in conversation. Paraphasias, or naming errors, are a classic symptom of aphasia. Phonemic paraphasias involve the substitution, addition, or omission of target sounds (phonemes). For example, an individual may say “bable” for “table.” A semantic paraphasia occurs when an individual produces a word related in meaning to the target word (i.e., “fork” for “spoon”). The severity of impairment can vary for each modality of language (listening, reading, writing, recognition of numbers, and gesturing). Aphasia is not a result of decreased auditory or visual perceptual skills, disordered thought processes, impaired motor programming, or weakness or incoordination of speech musculature [1].

Apraxia of Speech

The most common sign of apraxia of speech is a struggle to speak. This struggle is a direct result of the difficulty in finding the correct position of the articulators (i.e., lips, tongue). Speech is often halting and may contain sound substitutions, distortions, omissions, additions, and repetitions [6]. The individual is aware of his or her speech errors and will attempt to correct them with varying degrees of success. Severe forms of apraxia of speech may result in the inability to produce simple words. Interestingly, most people with apraxia of speech can produce common everyday phrases or sayings (e.g., How are you? Have a nice day. Thank you.) without error. A symptom that commonly coincides with apraxia of speech is nonverbal oral apraxia, which is the inability to imitate or to follow commands to perform volitional movements with the mouth or tongue [6]. Apraxia of speech is not caused by muscle weakness, decreased tone, or incoordination, nor is it the result of linguistic disturbances as in aphasia. Sound-level errors in apraxia of speech are thought to result from difficulty with motor execution and not with the selection of phonemes found in aphasia [4]. Apraxia of speech differs from dysarthria in that apraxia of speech is not a result of paresis or paralysis or the uncoordinated movements of speech muscles. Rather, it is believed to reflect a disturbance in the programming of movements used for speech [7]. In contrast to dysarthric errors, which are typically consistent and predictable, errors in apraxia of speech are highly irregular.

Dysarthria

In dysarthria, speech is often characterized as being slurred; the predominant errors are distortions of speech sounds. Dysarthria may also be characterized by changes in a person’s rate, volume, and rhythm of speech. The findings vary greatly, depending on the pathophysiologic mechanism. Table 154.3 presents an overview of dysarthria classification.

Table 154.3

Classification of Dysarthria

| Type | Localization | Motor Deficit |

| Flaccid | Lower motor neuron | Weakness, hypotonia |

| Spastic | Bilateral upper motor neuron | Spasticity |

| Ataxia | Cerebellum | Incoordination; inaccurate range, timing, direction; slow rate |

| Hypokinetic | Extrapyramidal system (basal ganglia circuit) | Variable speed of repetitive movements, rigidity |

| Hyperkinetic | Extrapyramidal system | Involuntary movements |

| Mixed | Multiple motor systems (amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, multiple sclerosis) | Weakness, reduced rate and range of motion |

Modified from Duffy JR. Motor Speech Disorders: Substrates, Differential Diagnosis, and Management, 2nd ed. St. Louis, Elsevier Mosby, 2005.

Dysphonia

Dysphonia is characterized by a reduction or alteration in voice quality. Vocal quality can vary by degrees of loudness, breathiness, hoarseness, or harshness. A common example of dysphonia is the hoarse vocal quality of individuals with laryngitis. In the extreme form, aphonia, the individual is incapable of producing any voice but may be able to produce voiceless speech (e.g., whispering).

Functional Limitations

Functional limitations depend on the nature and severity of the communication impairment. Severe deficits can impair the ability to express basic daily needs or to understand simple directions. The individual may not be able to effectively interact with family members or health care providers. Less severe deficits allow the individual to express and to understand basic information but impair high-level activities. These include the expression and understanding of complex and lengthy information to meet vocational or social needs. Speech and language impairments can affect an individual’s ability to complete a range of daily life tasks, including the ability to read bills and newspapers or environmental signs, to communicate using the telephone, and to participate effectively in conversations or school or employment activities. Speech and language impairments may result in frustration and can cause disruptions in personal relationships, community and religious participation, and vocational functioning. Individuals with aphasia often participate in fewer activities and report worse quality of life even when physical limitations, well-being, and social support are comparable to those of other individuals [13].

Diagnostic Studies

The speech-language pathologist or neuropsychologist can administer a variety of standardized instruments to diagnose aphasia. The aim of these instruments is to identify the pattern of symptoms to classify the aphasic syndrome, which is critical for the development of individualized interventions. Similarly, there are structured assessments for the diagnosis of dysarthria, dysphonia, and apraxia of speech. Performed by a speech-language pathologist, these in-depth assessments involve an oral-motor examination to identify the structure and function of oral, pharyngeal, and laryngeal musculature as well as speech characteristics (i.e., rate, volume, and intelligibility). For determination of the etiology and pathophysiology of dysphonia, a referral to an otolaryngologist is warranted. Laryngoscopy is often necessary to evaluate both the structure and the function of the larynx. Biopsy is indicated when a mass lesion is noted. Stroboscopic examination of the larynx, electroglottography, and acoustic voice analysis may reveal subtle abnormalities of vocal fold motion and resulting acoustic parameters [14,15]. The voice spectrogram is sometimes useful for quantitative assessment of vocal features.

Treatment

Initial

Treatment of speech and language disorders usually requires referral to a speech-language pathologist. Initial treatment depends on the nature and severity of the disorder. The treatment plans for aphasia, apraxia of speech, dysarthria, and dysphonia vary greatly and must be individualized to meet each patient’s communication needs. Initial intervention may include education of the patient and family about the communication impairment and compensatory strategies to facilitate communication.

Rehabilitation

To maximize a patient’s communication skills, a speech-language pathologist can offer specific strategies, exercises, and activities to regain functional communication abilities.

Aphasia

Aphasia rehabilitation is efficacious in the stroke population [16,17]. Intervention depends on the aphasia subtype and the individual’s specific strengths and weaknesses. General models of aphasia therapy involve stimulating intact language processes, facilitating maximal language and speech processes through hierarchical cues and prompts, and compensating for refractory deficits through alternative communication systems and partner-facilitated communication strategies [18]. Common therapeutic activities may involve naming tasks that use hierarchical cueing techniques to improve language content and structure. Therapy may begin with the production of automatic speech tasks, such as stating numbers or the days of the week. More difficult tasks may involve individually naming objects and describing pictures using appropriate sentence and word forms. Errorless naming techniques and gestural training can promote recovery of word retrieval [19]. The training of scripts can allow the individual to produce rehearsed sentences to meet needs in specific situations [20]. Written expression can be targeted through functional activities such as writing and copying biographical information. Common activities to improve auditory comprehension include following simple or complex commands and answering spoken questions correctly. Therapy to improve reading comprehension may involve matching objects to written words, following written directions, or reading functional information (bills, medication labels, environmental signs). Activities that involve attention training, problem solving, and executive functioning skills were shown to have a positive effect on verbal expression and auditory comprehension [21,22]. Furthermore, collaboration between the speech-language pathologist and other skilled services, such as occupational therapy, can improve the patient’s daily living skills.

Treatment for aphasia includes education. It is important to teach the individual with aphasia, family, and health care providers compensatory strategies to facilitate communication. Environmental modification and partner-facilitated approaches can dramatically improve communication success [23–25]. These can include turning off the television to reduce distractions, speaking slowly, using simple language, offering a pen and paper, checking that you are understood, and paraphrasing. Effective word-finding strategies include the use of circumlocutions, such as descriptions, definitions, or even sound effects during communication breakdowns. Training of volunteers to serve as conversation partners by the Supported Conversation for Adults with Aphasia intervention has been shown to be effective [26].

Advances in computer technology have provided therapists with new options in treating aphasia. Computer programs allow clinicians to easily design activities, to select stimulus items, to present cues, and to individualize reinforcements [27,28]. Software programs also can be used to turn a computer into a speech output communication device, allowing people with severe aphasia to produce phrases and sentences of varying degrees of complexity [29–31]. These programs often contain features such as word prediction and graphic cues to facilitate correct sentence structure. Video technology has allowed individuals with aphasia to follow pre-recorded mouth movements with auditory and written cues to aid word retrieval for full sentences and even longer narratives [32,33]. The growing popularity of user-friendly smart phones has allowed individuals with aphasia and other speech disorders easy access to tools for enhancing communication including photos, videos, maps, pre-recorded messages, and text support.

Recent changes in reimbursement for aphasia therapy encouraged development of the Life Participation Approach to Aphasia. This philosophy focuses on long-term life goals, incorporating “aphasia-friendly” environments, use of communication partners, and identification of barriers to life participation [34].

Dysarthria

Rehabilitation for dysarthria also depends on the specific subtype. Approaches to treatment include medical intervention, oral prosthetic devices, and behavioral management [6]. For example, people with dysarthria due to Parkinson disease may benefit from dopamine agonists. Palatal lifts and voice amplifiers are commonly used to improve intelligibility. A palatal lift and augmentation prosthesis have been used successfully in conjunction with behavioral management [35]. Behavioral management of dysarthria involves muscle strengthening (e.g., lip closure, tongue protrusion, tongue elevation), improvement of breath support, and modification of posture. The person with dysarthria learns to use compensatory techniques to decrease rate of speech, to increase loudness, and to “overarticulate.” As with aphasia, the family is educated in strategies to maximize communication. Treatment of severe dysarthria or aphasia can include use of an augmentative communication system in which the individual uses pictures, written words, and alphabet or pictograph boards to enhance communication. Some individuals can use computer systems that produce synthesized speech. These offer a wide variety of communication topics and can be personalized to the individual’s needs.

Apraxia of Speech

Treatment of apraxia of speech involves techniques to elicit accurate voluntary speech production. The speech-language pathologist incorporates multimodality cues, such as modeling mouth and lip movements, using verbal cues to describe accurate tongue and lip placement, and intoning words and sentences. Treatment approaches often incorporate the use of rate and rhythm control strategies [4]. For severe cases, alternative communication strategies, such as writing, drawing, and communication books, are used to augment or to replace speech.

Dysphonia

Management of dysphonia is based on the underlying disorder and the pathophysiologic process [36]. Vocal hygiene education and proper voicing techniques can improve vocal quality for individuals with vocal nodules due to laryngeal hyperfunction (vocal abuse). Techniques to enhance vocal fold approximation are useful in individuals with vocal cord motion impairments. Laryngitis due to gastroesophageal reflux disease is treated with a combination of voice therapy and vigorous antireflux regimen including proton pump inhibitors [37].

Procedures

Injection of a paralyzed vocal cord with Gelfoam or Teflon can increase its mass, bringing the medial edge of the cord closer to the midline. This facilitates contact with the mobile contralateral vocal cord, thereby improving phonation. This solution is usually only temporary; however, surgery is helpful in some cases. For cases of spasmodic dysphonia, an injection of botulinum toxin into the affected muscles can result in improved voice by correcting the abnormal motion of the vocal folds [38].

Surgery

Surgery is sometimes needed for treatment of voice disorders. Individuals with mass lesions of the larynx may need surgical excision. For individuals with unilateral vocal cord paralysis, a surgical procedure can bring the paralyzed cord closer to midline to achieve appropriate glottal closure. Implantation of a small device into the paralyzed hemilarynx, pushing the paralyzed cord toward the midline, can provide a lasting improvement in voice quality.

Structural lesions (e.g., cleft palate) or functional disorders (e.g., weakness of the palatal elevators) may cause inadequate seal of the velopharyngeal isthmus (the space between the soft palate and the pharyngeal walls). In either case, a surgical procedure to narrow the defect can sometimes provide improved speech quality.

Potential Disease Complications

Individuals with severe speech and language disorders may suffer extreme psychosocial consequences, including isolation, unemployment, depression [39], alienation, ostracism, and inability to fulfill essential family roles. Aphasia has been shown to be a risk factor for disability after stroke and plays a significant role in quality of life issues [40].

Potential Treatment Complications

Injection or surgical implant of the larynx may result in complications including infection, hemorrhage, and local tissue trauma. Injected material may gradually slip out of place and lose effectiveness, but this rarely leads to serious sequelae. Botulinum toxin injection rarely causes airway obstruction if the vocal folds become immobilized in the medial position. Leakage of the toxin into adjacent muscles may worsen the voice disorder or produce dysphagia.