CHAPTER 153

Spasticity

Joel E. Frontera, MD; Monica Verduzco-Gutierrez, MD

Definition

Spasticity is commonly defined as a velocity-dependent increase in muscle tone with exaggerated tendon jerks, resulting from hyperexcitability of the stretch reflex. This means that the faster the passive movement of the limb through its range, the greater the increase in muscle tone. This definition makes spasticity a component of an upper motor neuron syndrome, which is also associated with other findings that include hyperreflexia, clonus, muscle co-contraction, and muscle weakness.

Spasticity can be caused by a variety of upper motor neuron conditions. It is often noted to be a major problem in conditions like spinal cord injury, multiple sclerosis, and traumatic brain injury. It is estimated to affect between 40% and 80% of patients with a spinal cord injury or multiple sclerosis and as much as 80% of the traumatic brain injury population. It can also be present in other conditions like amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, brain and spinal cord tumors, and cerebral palsy.

Symptoms

Patients may complain of increased tightness, worsening spasms, and pain when they come to the clinic, but more important, the main complaint can be worsening of functional activities. The ability to move affected limbs actively or passively is reduced. Spasticity significantly interferes with routine tasks and even hygiene (e.g., increased elbow flexor spasticity in a stroke survivor while walking; adductor spasticity in a paraplegic individual during urinary catheterization) while at the same time causing pain and muscle co-contraction. These symptoms may be due to a secondary condition that may increase spasticity, such as an infectious process, skin problems, and cord tethering. Thus, when a patient comes to the clinic complaining of worsening spasticity, a thorough history and physical examination should be performed to identify the cause.

Physical Examination

Spasticity occurs in the presence of other signs and symptoms of upper motor neuron damage. Other positive signs include hyperreflexia, Babinski responses, and clonus. Negatives signs include muscle weakness, fatigue, reduced motor control, and loss of coordination. Increased muscle tone in the absence of these findings should lead to consideration of alternative causes of increased muscle tone, such as dystonia, Parkinson disease, or pain-associated muscle spasm. Strength testing may not be reliable as the spasticity may affect both range of motion because of contractures and co-contraction of antagonist muscles.

Muscle contracture as well as other soft tissue changes can be a part of this upper motor neuron syndrome, and it may be difficult in some cases to determine how much contracture is present in an individual with severe spasticity. A thorough physical examination can discover other issues associated with spasticity that could affect the individual, such as sensory disturbances (proprioception and spatial orientation), dysphagia, dysarthria, and skin issues. The skin should be inspected because abnormal positioning due to spasticity may directly cause skin injury (e.g., maceration of the palm due to a clenched fist) or contribute to pressure ulcer formation.

Sometimes it is important to differentiate spasticity from rigidity, commonly seen in conditions like Parkinson disease. One must look at some physical examination findings that occur with spasticity, such as the clasp-knife phenomenon. There is also variability when antagonistic muscles are evaluated. In spasticity, for example, some muscle groups are more affected than their antagonist muscles. Rigidity is not velocity dependent; it is constant throughout the full range of motion.

Functional Limitations

Spasticity can cause significant functional limitations. In a patient with spinal cord injury, for example, spasticity can have a serious impact on positioning. It can affect wheelchair positioning as well as transfers. Hygiene and catheterization may be affected by significant hip adductor tone or spasticity. It will affect dexterity and fine motor coordination in the upper extremities. The use of bracing or other modalities to assist with ambulation may be limited if the spasticity is significant. Studies have found that a significant number of patients with both spinal cord injury and traumatic brain injury have noted that spasticity affects quality of life. In some cases, spasticity may serve as a partial substitute for voluntary muscle contraction. A common example of substitution for voluntary muscle function is the hip and knee extensor spasticity seen after stroke that may allow successful weight bearing through the weak leg and contribute to restoration of walking ability.

Diagnostic Studies

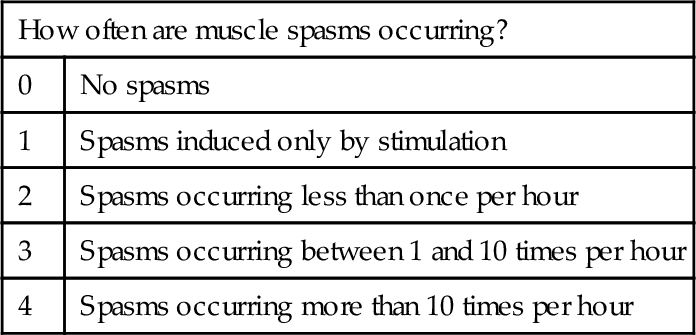

Spasticity is a clinical diagnosis, without any specific laboratory confirmation. Clinical measurement scales to quantify the severity of spasticity may be useful to monitor the efficacy of treatment. The most commonly used scales are the Ashworth scale (and a modified version of this scale) [1], which measures resistance of the muscle to passive stretch, and the Penn Spasm Frequency scale, which characterizes the frequency of muscle spasms [2] (Tables 153.1 and 153.2).

Table 153.1

Modified Ashworth Scale [1]

| 0 | No increase in muscle tone |

| 1 | Slight increase in muscle tone, manifested by a catch and release or by minimal resistance at the end range of motion when the part is moved in flexion or extension/abduction or adduction |

| 1+ | Slight increase in muscle tone, manifested by a catch, followed by minimal resistance throughout the remainder (less than half) of the range of motion |

| 2 | More marked increase in muscle tone through most of the range of motion, but the affected part is easily moved |

| 3 | Considerable increase in muscle tone, passive movement is difficult |

| 4 | Affected part is rigid in flexion or extension (abduction or adduction) |

Treatment

Initial

Management of spasticity should always be decided in the setting of functional and clinical scenarios. As noted before, spasticity can be used to the patient’s advantage, such as ambulation in the setting of spastic hemiparesis. Treatment should be started when spasticity becomes an obstacle to functional goals as well as to safety (spasms while transferring that could lead to a fall), hygiene, and skin integrity management. A change in previously well controlled spasticity should always lead to consideration of possible irritants or nociceptive stimuli that might be “triggering” the spasticity. Examples are urinary tract infections, skin breakdown, occult fractures, and an ingrown toenail in an insensate limb (e.g., in a paraplegic person).

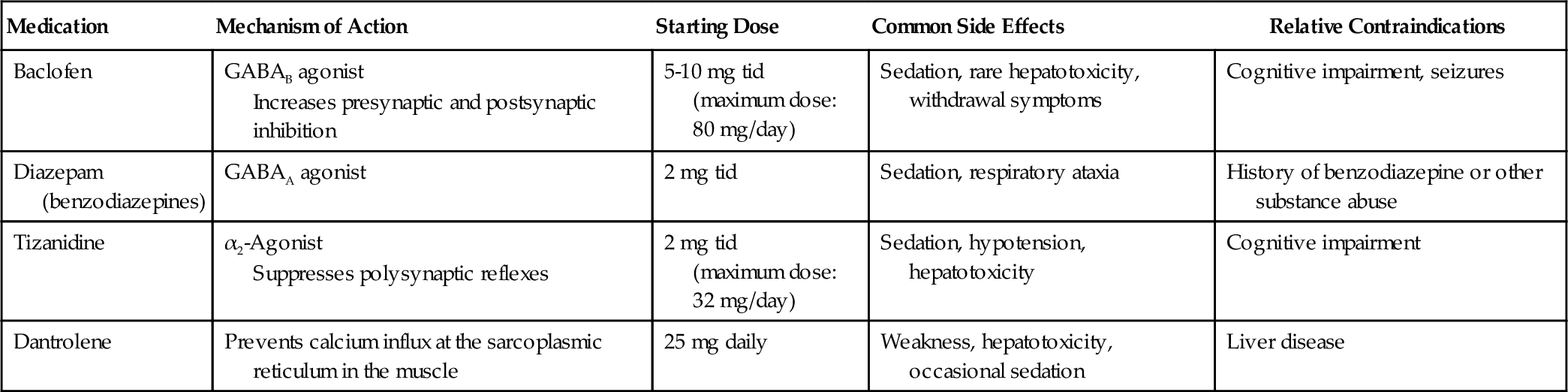

There are several options for oral medications (Table 153.3) that have had mixed results in the different diseases that cause spasticity. Spasticity caused by injury to the spinal cord tends to respond better to oral medications such as baclofen and tizanidine than does spasticity caused by a traumatic brain injury or a stroke. Some of the centrally acting medications, such as baclofen, tizanidine [3], and the benzodiazepines, have significant side effects that may impair cognition and overall recovery after an acquired brain injury [4]. Another commonly used drug is dantrolene [5], which works directly at the muscle level, preventing calcium flux at the sarcoplasmic reticulum and thereby reducing muscle force.

Rehabilitation

A physical management program of therapeutic exercise, stretching, and passive range of motion initiated by trained physical and occupational therapists is imperative for the management of spasticity, regardless of cause. Goals of therapeutic exercise are to maintain range of motion, to prevent contractures, to reduce muscle overactivity, and to disrupt maladaptive spasticity patterns. Active exercise can also increase muscle strength [6].

Stretching and passive range of motion serve to prevent contracture formation and temporarily reduce increased muscle tone, especially in patients who are not capable of active movement. Therapists can instruct the patient and caregivers in appropriate stretching techniques. Standing has been shown to be helpful in tone management as well as to have many other benefits. Physical modalities including ultrasound treatment have been used to facilitate stretching, although ultrasound had no effect in minimizing the spasticity at the gastrocnemius compared with passive stretching exercises in one trial [7]. The results of a different study did show that neuromuscular electrical stimulation with stretching of the wrist extensor muscles was more effective than stretching alone in reducing spasticity [8]. External cooling of a spastic limb may provide a temporary reduction in spasticity, but this modality is generally impractical as a long-term therapy.

Splinting is another imperative treatment in a comprehensive spasticity rehabilitation program. This can include prefabricated splints, low-temperature thermoplastic custom orthotics, and plaster or fiberglass casts. Serial casting has been shown to be effective both on its own and after botulinum toxin treatment in improving both passive range of motion and the modified Ashworth scale score [9].

Procedures

Treatment with injections is an effective means of obtaining substantial reduction in spasticity in specific muscles while minimizing the risks of systemic or sedating side effects. Prior to botulinum toxin, two compounds have been used for local muscle relaxation: local anesthetics (lidocaine, etidocaine, and bupivacaine) and alcohols (ethyl alcohol and phenol). Local anesthetic injections have a fully reversible action and are of short duration; therefore, they can be useful in assessing the efficacy and benefits of more permanent injections. Chemical neurolysis with phenol in concentrations of 5% to 7% and alcohol in concentrations of 45% to 100% have an advantage of lower cost, rapid onset of action, and potency but have risks of dysesthesias and muscle fibrosis and require more skill and time to perform [10].

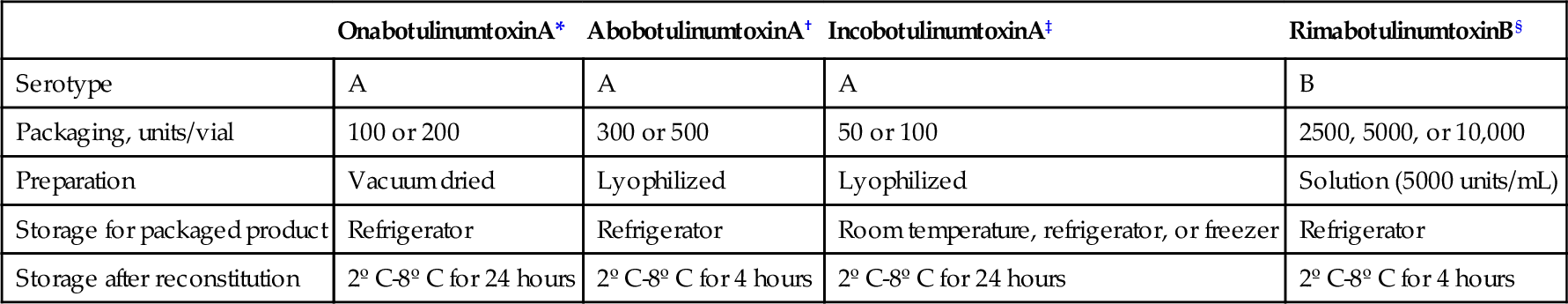

Chemodenervation with botulinum toxin has become a mainstay of practice in the treatment of spasticity for graded relief in selected muscles. Intramuscular injection of botulinum toxin provides local relief of spasticity for 2 to 6 months. There are currently four toxins available: onabotulinumtoxinA, rimabotulinumtoxinB, abobotulinumtoxinA, and incobotulinumtoxinA. There is ample literature on and Food and Drug Administration approval of all four agents for the treatment of cervical dystonia. There are now more publications on the type A products that document their utility in the management of spasticity [11–14]. The American Academy of Neurology published an evidence-based position paper on spasticity in 2008 supporting the use of botulinum toxin as a treatment to decrease tone and to improve passive function. In addition, it should be considered to improve active function [15]. Furthermore, with all injection procedures, adjunctive treatments such as physical and occupational therapy will improve the delivery of therapy and improve the outcome [16]. The dosing and administration of botulinum toxins are not standardized and must be managed with great care as they are not clinically equivalent. Some differences in the four botulinum toxins are shown in Table 153.4.

Table 153.4

Characteristics of Different Botulinum Toxins

| OnabotulinumtoxinA* | AbobotulinumtoxinA† | IncobotulinumtoxinA‡ | RimabotulinumtoxinB§ | |

| Serotype | A | A | A | B |

| Packaging, units/vial | 100 or 200 | 300 or 500 | 50 or 100 | 2500, 5000, or 10,000 |

| Preparation | Vacuum dried | Lyophilized | Lyophilized | Solution (5000 units/mL) |

| Storage for packaged product | Refrigerator | Refrigerator | Room temperature, refrigerator, or freezer | Refrigerator |

| Storage after reconstitution | 2º C-8º C for 24 hours | 2º C-8º C for 4 hours | 2º C-8º C for 24 hours | 2º C-8º C for 4 hours |

* Botox medication guide. Allergan. www.allergan.com

† Dysport medication guide. Ipsen Biopharmaceuticals. www.dysport.com

‡ Xeomin medication guide. Merz Pharma. www.xeomin.com

§ Myobloc medication guide. Solstice Neurosciences. www.myobloc.com

Surgery

Several surgical interventions are used for spasticity. An important neurosurgical intervention is placement of an intrathecal baclofen pump into the abdominal wall. In this system, there is an infusion of a prescribed rate of baclofen that is administered to the intrathecal space through a catheter system. This intervention has been found to reduce severe spasticity of cerebral and spinal origin, including in patients with cerebral palsy, spinal cord injury, brain injury, multiple sclerosis, and stroke. Evidence suggests that not only can intrathecal baclofen reduce spasticity, it can also improve function and quality of life [17] as well as improve gait in ambulatory patients [18,19].

Other neurosurgical techniques include stereotactic ablation or stimulation and cerebellar stimulation, which have been shown to have variable to uncertain results. Spinal cord surgeries such as selective posterior rhizotomy and myelotomy have been used as well in specially selected patients.

Neuro-orthopedic consultation can be obtained for further correction of limb deformities when conservative measures performed by a multidisciplinary team have been ineffective. Surgical procedures including tendon release or lengthening, tenotomy, and joint fusion can lead to improvement in functional outcome, pain, and subjective satisfaction [20,21].

Potential Disease Complications

Permanent loss of range of motion and contracture can result from inadequately controlled spasticity or insufficient stretching and splinting. Lost range of motion can also lead to difficulty with dressing, hygiene, and grooming activities. Skin issues can result, including accumulation of moisture, skin irritation, bacterial overgrowth, infection, and skin breakdown. Bone and joint issues, such as adhesive capsulitis, complex regional pain syndrome, and subluxation of joints, can occur.

Potential Treatment Complications

All of the centrally acting medications can cause significant sedation, which limits and therefore determines the dosage that can be tolerated. In individuals with preexisting cognitive impairments (e.g., stroke, traumatic brain injury), the sedative side effects can hinder rehabilitation goals, and the maximally tolerated dosage may be insufficient to control the symptoms of spasticity. Alternative treatments or use of the agents only before bedtime can be considered. Abrupt discontinuation of oral antispasticity medications is inadvisable. Seizures have been described after abrupt discontinuation of baclofen, and rebound spasticity is a concern with all of these medications.

In individuals with marginal motor function who may be relying in part on spasticity as a substitution for voluntary motor control, excessive reduction in spasticity may lead to reduced functional ability (e.g., loss of the ability to stand in a patient with paraparesis). Oral medication or intrathecal baclofen doses can generally be titrated to avoid this side effect; however, injected treatments (botulinum toxin, phenol) are more of a problem if overtreatment occurs.

Phenol carries some risk for painful dysesthesia, muscle fibrosis, scarring, and edema after injection. Botulinum toxin is generally well tolerated in therapeutic doses but does carry a Food and Drug Administration–mandated black box warning of a rare but potentially life-threatening complication when the effects of the toxin spread far beyond the injection site, causing systemic weakness, vision changes, dysarthria, dysphonia, dysphagia, and respiratory insufficiency. This can be avoided by careful selection of muscles, proper method of injection guidance (e.g., electromyography, ultrasonography, or motor point electrical stimulation), appropriate dilution of toxin, and restriction of dosage to the minimal dose needed to obtain a therapeutic effect. Antibodies to botulinum toxin can develop after repeated injection, which can render treatment ineffective.

Intrathecal baclofen pump treatment can result in post–dural puncture headache, iatrogenic meningitis, or infection of the external surface of the pump. Complications can also involve the medication (e.g., known adverse effects of baclofen are drowsiness and weakness) but are more frequently the result of malfunction of the intrathecal baclofen therapy system due to the pump, catheter, or human error. Interruption or underdosing of drug delivery can lead to a life-threatening withdrawal syndrome. Catheter failures can result in need for surgical intervention.