CHAPTER 152

Scoliosis and Kyphosis

Definition

Scoliosis

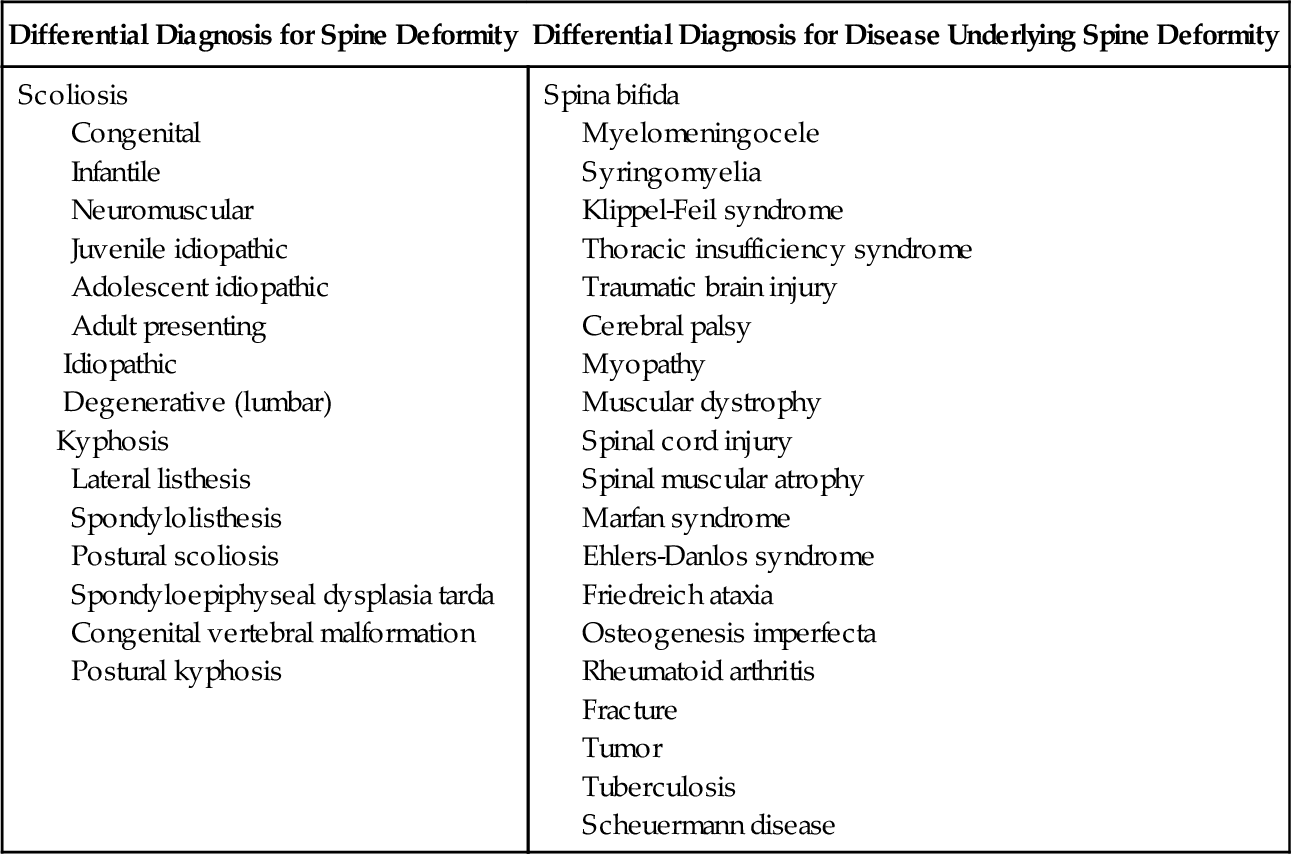

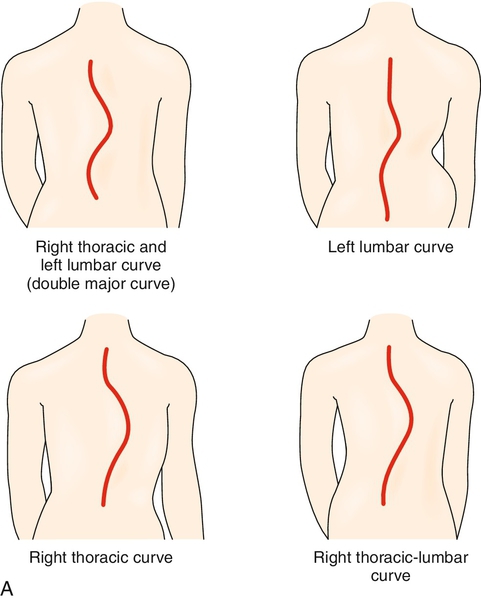

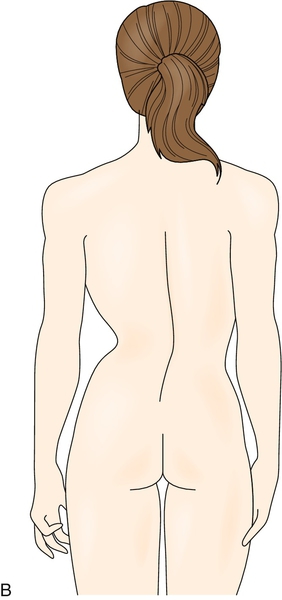

Scoliosis (Fig. 152.1) is a structural or postural deformity of the spine that results in a lateral (coronal) deviation or curve. Scoliosis is associated with rotation of the vertebral bodies located within the curve. It may also be associated with an arm or leg length difference, particularly in cases of idiopathic or congenital scoliosis.

Scoliosis is most commonly idiopathic, degenerative, or a result of vertebral anomalies. Less prevalent is scoliosis consequent to disease-related or iatrogenic causes. Growth asymmetry at the vertebral end plate, rib, and pelvic growth centers can result in scoliosis and progression of a scoliotic curve [1,2].

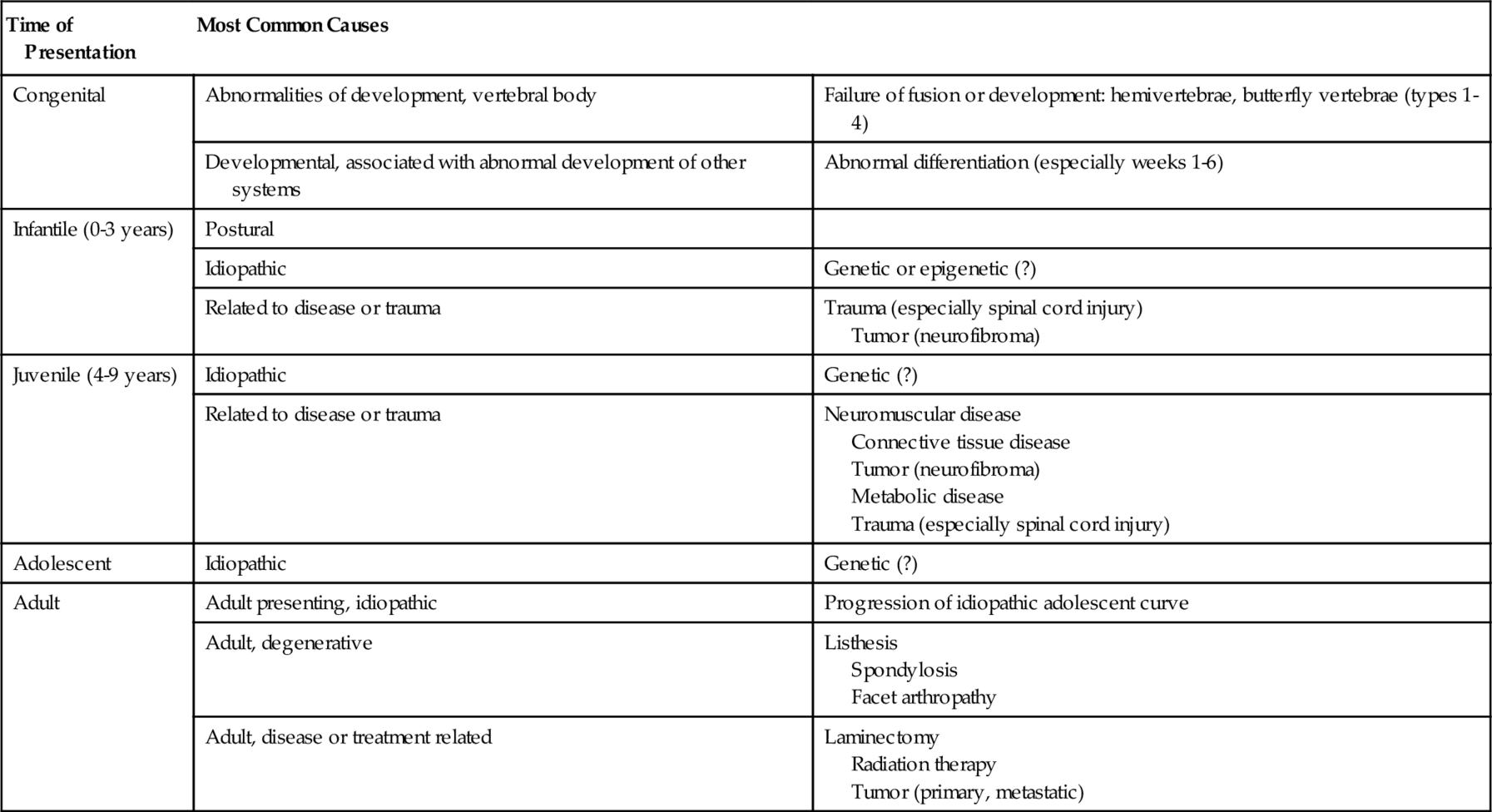

Scoliosis affects between 3% and 30% of the population; about 0.25% require treatment [3]. The incidence of scoliosis increases with age [4] (Table 152.1). The scoliotic curve may be congenital; appear during infancy (infantile scoliosis); or develop in childhood (juvenile scoliosis), adolescence (adolescent scoliosis), or adulthood. When the diagnosis of scoliosis is made in an adult patient, the curve is identified as either adult onset (degenerative) or adult presenting (a previously undiagnosed idiopathic adolescent curve).

There is increasing evidence that idiopathic curves can result from genetic or epigenetic factors. Gene candidates have been identified in a genome-wide association study. Statistical associations with scoliosis exist for gene polymorphisms (interleukin receptor and vitamin D receptor genes; ATRX gene; and chromosomes 6, 9, 16, and 17) [5–8]. All are associated with idiopathic curves. Epigenetic factors that might contribute to the development of scoliosis relate to maternal age, spinal cord injury before the age of 5 years (96% prevalence of scoliosis), DNA methylation, and transient fetal hypoxia [9–12]. These are only associations, and at this time any causality or mechanism of action is unclear.

Other types of scoliotic curves can begin with degenerative changes in the spine, congenital malformation of the vertebrae (usually incomplete fusion—butterfly vertebrae or hemivertebrae), tumor, neuromuscular or connective tissue disease, trauma, surgery, or radiation therapy.

Kyphosis

Thoracic kyphosis is an excessive sagittal deviation in thoracic spine alignment, a dorsal apex curve exceeding 40 degrees. Possible causes include osteoporotic compression fractures (note that most of these fractures are asymptomatic and unidentified), direct trauma, chronic kyphotic posture, tumor, radiation therapy [13], and Scheuermann disease. A resulting wedge deformity of the vertebral bodies produces the malalignment. Animal studies suggest that gestational and neonatal hypovitaminosis D or alterations in calcium and phosphorus concentrations in neonatal feedings can play a role in the development of pathologic kyphosis. The incidence of kyphosis in animals studied with maternal vitamin D deficiency during gestation or with low calcium and phosphorus feed content was 32%. No similar humans studies have been published. Earlier presentation of the kyphotic deformity was seen in cases of maternal hypovitaminosis D [14].

Cervical kyphosis is pathologic. Infection (particularly tuberculosis), tumor, abnormal development of the cervical vertebrae, trauma, and advanced degenerative disease of the spine can produce cervical kyphosis. Kyphosis related to trauma (including laminectomy) or advanced degenerative changes in the cervical spine (due to disease such as rheumatoid arthritis or the mechanical changes that can occur over time) becomes more prevalent with advancing age. The most common tumors are manifested early in life as osseous or neural extramedullary masses. They include (in order of decreasing frequency) chordoma, bone cyst, Ewing sarcoma, meningioma, schwannoma, and neurofibroma [15]. As a feature of the congenital cervical vertebral dysmorphic syndromes, cervical kyphosis is noted in the following syndromes: Down, Morquio, Goldenhar, Klippel-Feil, Stickler, Williams, and Larsen [16].

Symptoms

Scoliosis

Scoliosis is usually asymptomatic. If symptoms are present, they generally are produced by scoliosis as it directly relates to the location and severity of the curve. Large or highly rotated curves can produce pain and have the potential to produce symptoms related to the cardiopulmonary or nervous systems. Curves that exceed 60 to 80 degrees begin to affect other organ systems. They can produce shortness of breath or poor endurance due to decreased lung capacity. If there is pressure on nerve roots or the spinal cord, the patient may experience paresthesia or hypesthesia, weakness, and bowel or bladder involvement.

There is some controversy as to whether cosmetic changes related to thoracic scoliosis contribute to low self-esteem, anxiety, and depression (particularly in adolescents). Quality of life indices do not differ for adults by the age of 30 years [17].

Musculoskeletal pain may occur in performing activities of daily living that require a full active range of shoulder motion, such as overhead or extended reach activities. There may be upper back and neck pain in lifting or carrying because of strain of the scapular or shoulder muscles.

Kyphosis

Thoracic kyphosis is usually asymptomatic. If symptoms do appear, they are commonly associated with intermittent aching back pain and stiffness that are most prominent at the apex of the curve. Compensatory lumbar lordosis can be associated with low back pain.

Kyphosis with a wide scapular spread and shoulder and head protraction restricts both shoulder range of motion and the ability to look upward. When the ability to compensate for this with cervical or lumbar motion is compromised, kyphosis results in difficulty in performing overhead activities. Patients with cervical kyphosis may also complain of neck pain and the inability to look upward.

Physical Examination

Scoliosis

Scoliosis is usually apparent on inspection, although small thoracic curves with minimal rotation or a small lumbar curve can be difficult to detect. Have the patient bend forward (Adam forward bend test). If pelvic and lower extremity asymmetries affect the appearance of the back, minimize these by examining the patient in a seated position. Vertebral body or rib rotation associated with scoliosis is most readily seen when the patient bends forward. The tilt of the back, reflective of the angle of rotation, can be quantified by the use of a type of level, the scoliometer. The level is placed on the forward bent back in the area of maximum tilt and measures that angle. In idiopathic thoracic scoliosis, an angle of 7 degrees roughly corresponds to a scoliotic curve between 10 and 20 degrees.

Scoliosis can produce apparent asymmetry of breast size, asymmetry of the waist fold contour, asymmetric appearance of arm or leg length, or unequal iliac crest and shoulder height. A true leg length discrepancy exceeding 2.2 cm is indicative of asymmetric growth and possible scoliosis [18].

Serial assessment of scoliosis is advisable. The frequency of evaluation varies with curve parameters and treatment but is generally between 6 and 12 months, more frequently with curves that are progressing or being treated. These assessments focus on the degree of curvature, location and extent of the curve, degree of rotation, degree of skeletal maturity, flexibility of the curve, height, vital capacity, and expiratory pulmonary function tests.

Patients with degenerative scoliosis should be examined for neurologic deficits. Lower extremity strength, sensation, and reflexes can be impaired if the curvature exceeds 40 degrees.

Congenital vertebral malformations arise during the first 6 weeks of gestation. Symptoms and signs may be identified that relate to other systems in early development at that same time, particularly cardiac and renal.

Kyphosis

Increased thoracic kyphosis displaces the head and neck forward, and this forward displacement can be measured as an occiput to wall distance. A compensatory increase in lumbar lordosis can occur. These are apparent on inspection. The rounding of the back will not fully correct with trunk extension in a prone position, but the degree to which the curve decreases with active extension of the neck and upper back should be used as a benchmark for subsequent evaluations. Severe cervical kyphosis can produce a chin on chest appearance, but smaller curves are also readily apparent. Thoracolumbar and lumbar kyphoses are less easily identified on inspection. Prominence of the spinous processes can indicate lower spine kyphosis [19]. Kyphosis-associated scoliosis will be present in about one third of patients [20]. Restrictions in active trunk and neck extension can result from either deformity or pain. Tightness of the pectoral muscles is common.

A neurologic examination should be performed if there are radicular or myelopathic symptoms.

Functional Limitations

The functional limitations related to scoliosis and kyphosis result from the loss of spinal motion. Restriction in upper back extension can reduce upward gaze and affect driving or cause discomfort in lying prone or swimming in a prone position. Loss of shoulder range of motion, particularly forward flexion and abduction, can result from a decreased range of scapular excursion over the scoliotic or kyphotic thorax. This impedes overhead activities of daily living. When present, pain and stiffness can limit sitting, standing, or walking tolerance.

Disruption of spinal balance displaces the center of gravity, particularly with large uncompensated curves. This increases the energy costs for standing and ambulation. It can also impair balance. With severe deformity and cardiopulmonary compromise, endurance is diminished. Cosmetic deformities that affect self-image or self-esteem can lead to social isolation. Age-related changes in anatomy and physiology can compound the impairments and restrict mobility or cause disability associated with the activities of daily living.

Diagnostic Studies

Standing anteroposterior and lateral radiographs are the standard diagnostic tests used to evaluate scoliosis and kyphosis. Radiographs can reveal congenital abnormalities of the vertebral body, Scheuermann disease, or lateral vertebral body wedging [21]. Bending or supine radiographs are not usually obtained but can help determine the flexibility of the curve. Non–weight-bearing radiographs and serial radiographs, both in the brace and out of the brace, may offer some advantage in estimating possible correction, actual correction, and the effectiveness of bracing [22].

Rib-vertebral angle and space available for lung (reported to be useful in cases of infantile scoliosis) are less common but available x-ray assessments. The difference in angle magnitude or ratio of angles between the convex and larger concave rib-vertebral angles in the thorax can be sensitive indicators of change [23,24].

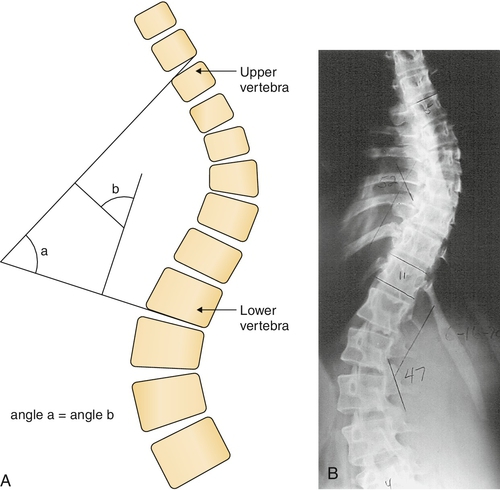

X-ray measurement of the scoliotic curve is commonly done by the Cobb method. The Cobb angle is the angle at the intersection of lines drawn perpendicular to the vertebral end plates that frame the curve—those with the maximal tilt (Fig. 152.2).

Radiographs can demonstrate vertebral body rotation and the status of growth centers in the ilium, vertebrae, and humerus. The degree of vertebral body rotation is gauged by the deviation from midline of the spinous process or fullness of the pedicle silhouette. Rotation is graded 0 (no rotation) to 4 (rotation of 90 degrees or more). Closure of the growth plates proceeds in a cephalad manner. Because vertebral growth plates are usually not visualized, iliac and femur epiphyses are useful sites for assessing spine growth status. Growth status is graded 0 (no mineralization) to 5 (fusion of the growth plate). Radiographs can help assess the growth or degenerative status of the spine, useful information for determining a plan of care.

Magnetic resonance imaging can identify an unsuspected pathologic process, for example, a neurofibroma, diastematomyelia, or tethered cord. Magnetic resonance imaging is recommended before surgery as an otherwise undetectable spinal cord abnormality is present in about 10% of cases slated for surgery [25].

Bone scans can help exclude discitis or tumor as a cause of pain or spinal deformity. Bone densitometry demonstrates increased density on the convex side of the curve. This occurs even in osteoporotic patients [26]. Pulmonary function testing, particularly volume and expiratory studies, should be performed when curves exceed 50 degrees. Genetic testing for markers associated with scoliosis is available but not useful at this time.

Treatment

Initial

The broad categories of treatment for scoliosis and kyphosis include observation, bracing, and surgery. The problems needing treatment fall into the categories of pain, deformity, deficit, and disability.

In all patients, regardless of age, it is important to identify curves that are likely to progress. Curves that are large (degree of curvature), particularly if they are “unbalanced” (e.g., a single major curve without a compensatory curve), are likely to progress. Other curves that tend to progress are those with a closely packed configuration (a small number of spinal segments between the apex and ends of the curve), congenital vertebral body malformation, and neuromuscular or lumbar degenerative disease etiology [27].

Lumbar degenerative scoliosis (this includes adult-presenting idiopathic scoliosis with subsequent degenerative change) is most likely to progress when L5 is involved or there are asymmetric changes in the L2-3 or L3-4 disc space.

In general, scoliotic curves that measure less than 20 degrees or kyphotic curves measuring less than 40 degrees are observed rather than treated with bracing or surgery. Observation can be supplemented by an exercise program.

Pain can be treated with bracing or exercise. Anti-inflammatory medication, analgesics, acupuncture, and transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation may be useful.

There is no clear role for electrical stimulation of paraspinal muscles in the treatment of scoliosis. Treatment of coincident disease, such as osteoporosis, complements the treatment of scoliosis and its attendant symptoms and disability.

Rehabilitation

Exercise is beneficial for general well-being, flexibility, and improvement of posture. There is no clear evidence that exercise is a disease-modifying intervention for idiopathic scoliosis [28]. There is, however, a specific exercise protocol for scoliosis, the Schroth method. These exercises attempt to correct growth imbalances in the back and to improve spinal alignment. There is anecdotal evidence that the Schroth method is useful in the treatment of small curves, particularly the component exercises of spinal extension, abdominal strengthening, and hamstring stretch. These exercises may also be helpful in treating back pain. Kyphosis may improve with cervicothoracic extension exercise and pelvic tilt to reduce lumbar lordosis, along with stretching and strengthening exercise of the hamstrings, hip flexors, and pectoralis muscles.

Physical therapy and occupational therapy should be prescribed as an appropriate part of a pain management plan as well as to optimize independent mobility and function in activities of daily living.

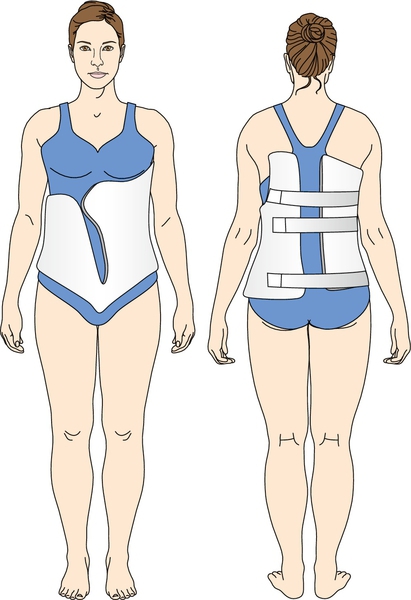

Bracing is an important part of the rehabilitation intervention when scoliosis is symptomatic or progressive. Scoliotic curves exceeding 20 degrees are 20% to 40% more likely to progress if a brace is not used, as is kyphosis in excess of 40 degrees.

Bracing for scoliosis is most effective for lower thoracic and lumbar curves. In the case of idiopathic adolescent scoliosis, an orthosis has the potential to provide good control. Stabilization of the curve occurs in 42% to 92% of cases, depending on the accuracy of brace prescription and patient compliance. Actual correction (reduction of the coronal deviation and rotation) with bracing, including serial casting, is more likely to happen in cases of infantile or juvenile idiopathic curves than it is for scoliosis at other ages [29].

There are many different orthoses in use, with a plethora of names [30]. The mechanics of bracing varies with brace type. Braces can be static (constant pressure and rigid containment) (Fig. 152.3) or dynamic (movement opposing the spine deviations, facilitated by flexible bands). Braces can work by derotation, three-point pressure correction, or distraction. Braces may need to be worn full-time or at intervals throughout the day (usually at night or during episodes of pain). Selection of the brace with the best control effect and the least discomfort or inconvenience depends on several factors. These factors include curve parameters, such as etiology, location, and rotation of the curve, but also symptoms and likely compliance with prescribed use [31].

In adolescent idiopathic scoliosis, the goal of orthotic treatment is to limit progression of the curve. There is no clear consensus regarding daily brace wear-time. Recommendations range from 8 to 23 hours. Bracing for idiopathic curves in a growing child or adolescent is maintained until the spinal growth centers fuse.

When a brace is used to decrease pain and to improve posture for patients with degenerative scoliosis, the brace is worn when needed. The most commonly prescribed brace is the thoracolumbosacral orthosis, such as a body jacket with wedges or pads. High thoracic and cervical scoliosis and kyphotic curves require a Milwaukee cervicothoracolumbosacral orthosis.

In cases of scoliosis associated with neuromuscular diseases, bracing guidelines are less clear. Bracing may be withheld while the patient is ambulatory. Braces can be useful as a means to delay surgical intervention. If a body jacket is provided, an abdominal window is needed to allow respiratory excursion.

Contoured or custom-molded seating systems that align and support the trunk can be useful in patients with neuromuscular disease. These accommodate the scoliotic curve while allowing the patient to maintain an upright posture while seated, improving head control and upper extremity function.

Procedures

There are no invasive physiatric procedures for the treatment of scoliosis or kyphosis.

Surgery

The goal of surgery is to stabilize the spine through correction or control of the deformity. Indications for surgical correction of scoliosis or kyphosis include progressive deformity, segmental instability, progressive or new neurologic deficit, and cardiopulmonary compromise. Pain, even when it is refractory to conservative management, is a controversial indication for surgery. Inability to use a brace or severe cosmetic deformity can be an indication for surgery in specific instances.

Scoliosis

A variety of surgical techniques and approaches address the coronal and rotational deformities. There are procedures that provide decompression to relieve scoliosis-related stenosis. There are surgical strategies to preserve or to promote growth of the spine in children and adolescents. Stabilization of the spine is the primary goal in any surgery, but there are multiple ways to achieve this stability.

Surgery for idiopathic (adolescent, adult presenting) scoliosis addresses the coronal and rotational deformities by derotation or distraction. The spine is stabilized with hardware with or without bone fusion.

Static stabilization of the spine is achieved through fusion. This eliminates any future growth at the fused segment and may not be the procedure of choice for a growing child, for whom dynamic stabilization may be the better option. For these patients, the goal of treatment is to foster balanced growth of the spine. In the youngest patients, a rib cage implant can do this. In cases of infantile or juvenile idiopathic scoliosis, some success with thoracoscopic stapling has been reported [32]. Semirigid rods or cords can be used to control spinal motion while promoting growth [33,34]. Growth rods are lengthened either surgically or magnetically about every 6 months [35]. A similar technique with dynamic stabilization (but without growth rods) that reduces or eliminates the adverse effects associated with static stabilization has also been reported in cases of degenerative scoliosis [36].

Lumbar degenerative scoliosis can be associated with radicular disease. Surgical options in such instances include various degrees of decompression and long (extending above and below the curve) or short fusion. The selection of the procedure is influenced by the location of the scoliosis, but when possible, long fusion is the better option [37,38].

Kyphosis

Various surgical approaches have been used to correct thoracic kyphosis. Combined anterior plus posterior instrumentation with fusion currently provides the highest success rate for lasting correction and pain relief [39].

Potential Disease Complications

Scoliosis and kyphosis can produce pain and reduce joint or segmental motion and result in disability. The deformity can progress and contribute to the development or worsening of spondylosis, facet arthropathy, spondylolysis, and spondylolisthesis. Such changes in spine structure and mechanics correlate well with large angles and angles of rotation at the curve apex [40]. Foraminal, lateral recess, or canal stenosis can occur with signs and symptoms of neurologic compromise. Root entrapment usually occurs on the concave side of the curve (rarely both convex and concave sides). Cauda equina compression has been reported, as has myelopathy [41].

Shortness of breath, poor endurance, and poor activity tolerance due to restrictive lung disease can occur as a complication of scoliotic curves exceeding 40 degrees or kyphosis in excess of 50 degrees.

Potential Treatment Complications

Most treatment complications follow surgery or bracing. Exercise-related complications are uncommon but include overuse conditions of the soft tissues (tendinitis, bursitis, sprain, strain).

Complications of bracing include skin breakdown, dermatitis due to an allergy to the orthotic material, hyperhidrosis, cutaneous infection, gastroesophageal reflux disease, esophagitis, and altered gastrointestinal motility. There can be shortness of breath, difficulty in sitting, low self-esteem, and altered body image.

Surgical complications include vascular or neurologic injury, pseudarthrosis, infection, graft donor site pain, progressive pelvic obliquity, painful degenerative changes in the segment adjacent to the level of fusion (especially low lumbar or at T11-T12), spine segment instability, hardware prominence or failure, and thromboembolism. Hardware complications include slippage of anchoring hooks, bending or fracture of a rod, wire pull-out, and hardware migration [42]. High complication rates are associated with the placement of growth rods. Progression of the curve is possible despite surgical fixation. The patient with degenerative scoliosis who has undergone otherwise successful surgery may continue to experience pain or restricted mobility and may need revision surgery at a later time.