CHAPTER 151

Rheumatoid Arthritis

Definition

Rheumatoid arthritis is a chronic inflammatory disorder that primarily affects joints but may also have prominent extra-articular features. The arthritis is classically symmetric and affects the peripheral joints. The prevalence of rheumatoid arthritis is approximately 1% in white individuals, and it affects women about 2 to 2.5 times more often than men, which may be related to the effect of sex hormones, such as estrogen, in regulating the immune response [1]. Peak incidence of rheumatoid arthritis is in the third and fourth decades, although the disease affects all ages and individuals from all racial and ethnic groups [2–4]. Classification criteria are available for rheumatoid arthritis and may be helpful in the evaluation of patients (Table 151.1). Many patients with early disease, however, may not fulfill these criteria [5].

Table 151.1

Classification Criteria for Rheumatoid Arthritis*

| Criterion | Definition |

| Morning stiffness | Morning stiffness in or around the joints lasting at least 1 hour before maximal improvement |

| Arthritis of three or more joint areas | Soft tissue swelling or fluid in at least three joints observed by a clinician The 14 possible joints include right and left proximal interphalangeal, metacarpophalangeal, wrist, elbow, knee, ankle, and metatarsophalangeal joints. |

| Arthritis of the hand joints | At least one area swollen in a wrist, metacarpophalangeal, or proximal interphalangeal joint |

| Symmetric arthritis | Simultaneous involvement of the same joint areas on both sides of the body Involvement of the small joint groups (metacarpophalangeal joints, proximal interphalangeal joints, and metatarsophalangeal joints) is acceptable without absolute symmetry. |

| Rheumatoid nodules | Subcutaneous nodules occurring over bone prominences, extensor surfaces, or juxta-articular regions These must be observed by a clinician. |

| Serum rheumatoid factor | Abnormal amounts of serum rheumatoid factor by any method for which the result has been positive in < 5% of normal control subjects |

| Radiographic changes | Posteroanterior hand and wrist films that demonstrate erosion or unequivocal bone decalcification localized in or most marked adjacent to the involved joints |

* A patient is said to have rheumatoid arthritis if he or she satisfies at least four of the seven criteria. Criteria one through four must have been present for at least 6 weeks.

Symptoms

Rheumatoid arthritis is a systemic disease, and symptoms vary according to the system involved [6–8].

General

Morning stiffness is a prominent feature of rheumatoid arthritis. Unlike the brief stiffness (5 to 10 minutes) that occurs in patients with osteoarthritis, the morning stiffness in rheumatoid arthritis may last for hours. Fatigue and generalized malaise are also common complaints.

Joint

Patients present with joint pain and swelling as well as loss of joint function, which may be due to joint inflammation or structural damage from cartilage destruction and bone erosion. A Baker cyst can develop and cause pain or swelling of the popliteal fossa. If the cyst ruptures, it may cause pain, swelling, and erythema of the calf. If the cricoarytenoid joint is involved, patients may complain of laryngeal pain, hoarseness, or difficulty in swallowing.

Eye

Up to one third of patients will complain of dry eyes (keratoconjunctivitis sicca). These patients may also complain of foreign body sensation, burning, or discharge. Patients with episcleritis will complain of red, painful eyes.

Skin

Patients may note small, painless subcutaneous nodules, mainly over the extensor surfaces. Rheumatoid vasculitis will cause a rash that may lead to ulceration. Patients with vasculitis may also complain of discoloration around the fingertips (digital infarcts).

Neurologic

Numbness and tingling are common symptoms of nerve involvement. Nerve entrapment may result from joint inflammation. The most common site is at the wrist, where median nerve involvement may cause carpal tunnel symptoms. Mononeuritis multiplex is the result of vasculitis and is manifested as weakness, numbness, or tingling in discrete nerve distributions (e.g., femoral, peroneal, or radial nerve, causing proximal leg weakness, footdrop, or wristdrop). Cervical spine instability may lead to myelopathy, causing sensory symptoms and weakness, most commonly in the upper extremities. This can occur in the absence of neck pain in patients with long-standing rheumatoid arthritis.

Cardiac

The incidence and prevalence of coronary artery disease are increased in any type of chronic inflammatory disorder, and this is especially evident in rheumatoid arthritis. Thus patients may present with complaints of chest pain, shortness of breath, diaphoresis, and other symptoms consistent with cardiac ischemia. Prevalence of angina in patients with rheumatoid arthritis may be less because of the relative inactivity. Other cardiac manifestations of rheumatoid arthritis include myocarditis, pericarditis, atrioventricular block, and cardiac rheumatoid nodules. Pericardial involvement is usually asymptomatic.

Pulmonary

Pleural inflammation or nodulosis may produce typical symptoms of pleurisy. Shortness of breath may occur secondary to pleural or interstitial disease.

Physical Examination

All joints are examined for swelling, warmth, effusion, range of motion, and deformity. Fingers, feet, wrists, and knees are most commonly involved. The distal interphalangeal joints are usually spared. In rare cases, patients will present with monarthritis (involvement of a single joint). Rheumatoid nodules are present in about 30% of patients and occur over bone prominences, over extensor surfaces, or in juxta-articular regions [6].

In the hands, early rheumatoid arthritis causes fusiform swelling at the proximal interphalangeal joint. Chronic inflammation may lead to subluxation of the metacarpophalangeal joints with ulnar deviation of the fingers. Damage to collateral ligaments at the proximal interphalangeal joints results in the classic boutonnière (proximal interphalangeal joint flexion and distal interphalangeal joint hyperextension) and swan-neck (proximal interphalangeal joint hyperextension and distal interphalangeal joint flexion) deformities (Figs. 151.1 and 151.2).

Symmetric wrist swelling is usually present. Subluxation results from synovitis and weakening of the ligaments and causes prominence of the ulnar styloid.

Inflammation of the synovial tendon sheath (tenosynovitis) may occur in the flexor or extensor tendons of the fingers. Examination reveals that passive motion is greater than active motion. Crepitus is often felt when the examiner’s hands are placed over the tendon sheaths and the fingers are flexed and extended. If the patient has a trigger finger, placement of one finger over the flexor tendon while the affected finger is flexed and extended will allow palpation of a nodule.

Elbow involvement is common. In early disease, inflammation and effusion cause decreased extension. Effusions can be palpated in the para–olecranon groove. In some cases, there may be pressure on the ulnar nerve. With chronic inflammation and erosion of the cartilage between the radius and ulna, loss of elbow extension and flexion occurs. Rheumatoid nodules are often found over the extensor aspect of the proximal ulna. The olecranon bursa may be enlarged and filled with fluid or nodules.

The shoulder may be involved in rheumatoid arthritis. Effusions are best seen on the anterior aspect of the shoulder below the acromion. Evaluation of rotator cuff strength is important because inflammation of the rotator cuff may result in tendinous destruction. The biceps tendon may rupture, causing a bulge in the biceps when it is flexed against resistance.

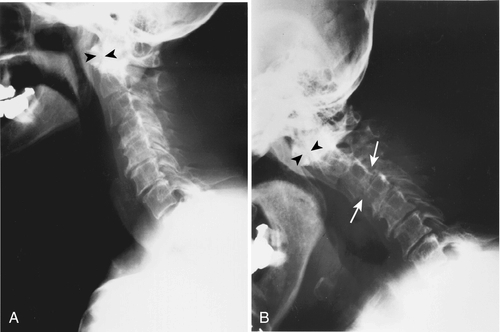

The cervical spine may have decreased range of motion or pain with range of motion. Patients with suspected cervical instability should have a thorough neurologic examination, checking for upper motor neuron findings. Patients with cord involvement may demonstrate paresthesias, weakness, or pathologic reflexes. Tingling paresthesias descending the thoracolumbar spine on flexion of the cervical spine are called Lhermitte sign.

The hip joint is deep, limiting evaluation for synovitis and effusion. An inflamed hip will cause groin pain on active and passive range of motion. Patients may walk with an antalgic gait, rapidly taking weight off the affected leg, or shorten their stride length. Pain in the hip may also result from trochanteric bursitis. Application of pressure over the lateral hip region reproduces the pain from the trochanteric bursa. Lateral hip pain and lack of groin pain distinguish trochanteric bursitis from joint inflammation. Iliopsoas bursitis may result in an inguinal mass.

The knee is commonly involved in rheumatoid arthritis. Small effusions can be detected by looking for a “bulge” sign. For the performance of this maneuver, the patient should be lying down. With one hand, the clinician makes an upward stroke to depress the medial synovial pouch. A downward stroke on the lateral aspect of the knee will result in a bulge of the medial pouch if a small effusion is present. A ballottable patella (patellar tap) indicates a larger effusion. Baker cyst occurs as an extension of synovial fluid from the joint cavity. The cyst causes fullness in the popliteal fossa that can be seen when the patient is standing with his or her back facing the clinician. Erythema and swelling of the calf may be seen if the Baker cyst has ruptured. Evaluation for hemorrhage below the malleoli of the ankle (the “crescent” sign) can distinguish this from thrombophlebitis.

The ankle may have synovitis, effusion, or decreased range of motion in the patient with rheumatoid arthritis. Involvement of the hindfoot (subtalar and talonavicular joints) may result in valgus deformity and flatfoot. Metatarsophalangeal joint involvement is common. Synovitis causes pain and fullness with palpation. Hallux valgus deformity is also common. Progressive disease causes dorsal dislocation of the metatarsophalangeal joints and claw toes.

Functional Limitations

Functional limitations depend on the location and severity of joint and extra-articular involvement. There may be limitations or pain with upper extremity movements or lower extremity motions, including gait. Criteria for the assessment of functional status have been established (Table 151.2) and are based on activities of daily living, including self-care (e.g., dressing, feeding, bathing, grooming, and toileting) and vocational (e.g., work, school, and homemaking) and avocational (e.g., recreational and leisure) activities [10].

Table 151.2

Criteria for Classification of Functional Status in Rheumatoid Arthritis

| Class I | Able to perform all activities of daily living (self-care, vocational, and avocational) |

| Class II | Able to perform self-care and vocational activities, but limited in avocational activities |

| Class III | Able to perform usual self-care activities, but limited in vocational and avocational activities |

| Class IV | Limited in all activities of daily living (self-care, vocational, and avocational) |

Whereas radiologic changes have limited value in determining functional impairment and quality of life, disability from rheumatoid arthritis has been directly attributed to joint damage, disease activity, pain, and depressive symptoms [11]. Patients with rheumatoid arthritis may have less disability conviction than those with other problems, such as low back pain.

Diagnostic Studies

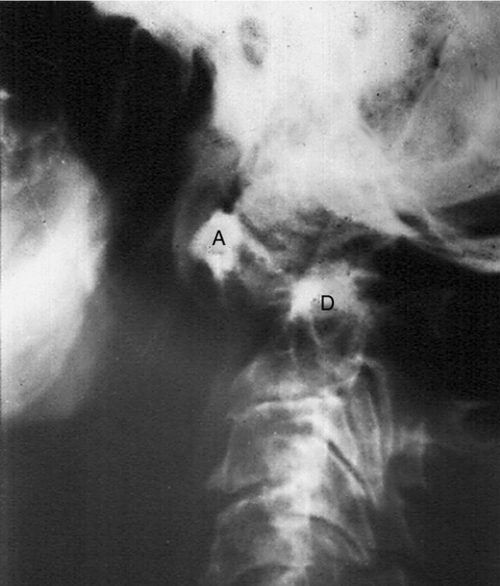

Laboratory histologic findings and radiographic findings may be suggestive of rheumatoid arthritis, but no test is diagnostic of the disease [6,12] (Figs. 151.3 and 151.4). Rheumatoid factor is present in the serum of 85% of patients [8]. However, because rheumatoid factor is often present in other inflammatory conditions, such as systemic lupus erythematosus, primary Sjögren syndrome, and chronic osteomyelitis, much debate exists about its utility in the diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis as a result of low specificity [13]. Anti–cyclic citrullinated peptide antibodies have shown more promise as potential biologic markers because of sensitivities of 70% to 80% and specificities of 95% to 98% in patients with established rheumatoid arthritis [14]. Normochromic, normocytic anemia consistent with chronic disease is often found, and the degree of anemia often correlates with disease activity. Acute phase reactants, such as erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein concentration, and erythrocyte and platelet counts, are elevated. Eosinophilia may be found in patients with extra-articular manifestations. Patients with Felty syndrome (rheumatoid arthritis, splenomegaly, and leukopenia) exhibit low white blood cell counts and may have thrombocytopenia. A variant of Felty syndrome has been described in which patients have large granular lymphocytes in blood and bone marrow in addition to neutropenia. Liver enzymes including aspartate transaminase and alkaline phosphatase are often elevated in patients with active disease.

Evaluation of fluid taken from an affected joint will show an inflammatory cell count (more than 2000 white blood cells). Joint fluid should always be sent for culture to rule out infection and evaluated under a polarized microscope to exclude crystal disease. If pleurocentesis or pericardiocentesis is necessary, the fluid has a low complement concentration, a high protein concentration, and a predominance of lymphocytes. The glucose concentration is characteristically extremely low or may even be absent.

Characteristic changes on joint radiographs include periarticular osteopenia and marginal erosions. Early in the disease, joint films may be normal. Baseline hand and wrist films may aid in diagnosis and can be used to follow disease progression. Flexion and extension views of the cervical spine may demonstrate erosion of the odontoid and atlantoaxial subluxation. Pulmonary nodules or interstitial fibrosis can be seen on the chest radiograph. Echocardiography often reveals a small pericardial effusion, valvular thickening, or aortic root dilation, but these are most often asymptomatic. Electrocardiography may reveal conduction abnormalities due to involvement of the cardiac conduction system by rheumatoid nodules.

Treatment

Initial

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are effective in some patients.

For patients with inadequate response to nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or poor prognostic indicators, disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) should be initiated. Poor prognostic factors include high-titer rheumatoid factor, early presence of bone erosion, many affected joints, extra-articular involvement, and considerable degree of physical disability at disease onset [9,15].

DMARDs that are prescribed include antimalarials, intramuscular administration of gold, sulfasalazine, azathioprine, methotrexate, leflunomide, cyclosporine, and cyclophosphamide [15,16]. Anticytokine therapies include the anti–tumor necrosis factor-α agents etanercept, infliximab, and adalimumab and the interleukin-1 receptor antagonist anakinra. Other biologic agents currently available include abatacept (CTLA4-Ig) and rituximab, which is a B cell–depleting monoclonal antibody. Several studies support the use of combination DMARD therapy [17]. Anti–tumor necrosis factor-α agents used in combination with small-molecule DMARDs such as methotrexate will often halt disease activity and radiologic progression of joint destruction [18]. Corticosteroids can be very useful and can be administered systemically as a bridge to therapy with DMARDs or intra-articularly for monarticular or oligoarticular involvement.

Patients who have persistent pain due to structural damage may need treatment specifically for the pain, with different medications. Depending on the patient, one may need to consider analgesics, anti-inflammatories, opioids, opioid-like drugs (tramadol), and neuromodulators to include antidepressants, anticonvulsants, and muscle relaxants [19].

Rehabilitation

Once the diagnosis is confirmed, it is important to work together with a rheumatologist to prescribe the most optimal rehabilitation treatment program. Static exercise regimens to maintain strength while protecting inflamed joints from adverse stress are recommended. Appropriate referrals to occupational or physical therapists for more specific treatment and splinting can be initiated by a physician, with close follow-up to determine whether the patient needs modifications or changes in the treatment program as the disease progresses. The physician can also address issues of pain, return to work, and maintenance of function important to the patient’s lifestyle.

The role of occupational and physical therapy may be different in early or established disease and end-stage disease [20,21]. In early disease, occupational therapy is directed toward education of the patient about how to minimize joint stress in performing activities of daily living. Splints may be used to provide joint rest and to reduce inflammation during the acute inflammatory phase. Splints may also allow functional use of joints that would otherwise be limited by pain. However, not all clinicians advocate splints as they can facilitate more joint stiffness if they are used routinely. Paraffin baths can provide relief of pain and stiffness in the small joints of the hands. Contrast baths are used to increase superficial blood flow, although the benefit for patients with rheumatoid arthritis is not clear [22]. In end-stage disease, the occupational therapist plays an important role, providing aids and adaptive devices, such as raised toilet seats, special chairs and beds, and special grips that can assist in self-care. By maximizing one’s functional ability, the occupational therapist can help prevent other physical or psychological problems [23]. Outcomes can include improvements in self-care, productivity at home and at work, and leisure time enjoyment [24].

Physical therapy can be helpful in reducing joint inflammation and pain. The therapist may employ a variety of techniques, including the application of heat in conjunction with passive stretch or cold for inflamed joints. Water exercise (hydrotherapy) is used to increase muscle strength without joint overload. In patients with foot involvement, small alterations to footwear or inserts may decrease pain and provide a more normal gait. In end-stage disease, the goals of therapy are to reduce joint inflammation, to enhance flexibility, to improve the function of damaged joints, and to improve strength in surrounding muscles and maintain a level of physical fitness.

Local immobilization may be used to reduce inflammation and pain. Nonfixed contractures may be prevented or improved with periods of splinting combined with goal-oriented exercise. Muscle strength and overall conditioning may be improved by static, range of motion, and relaxation exercises. In recent years, aerobic and weight-bearing exercises have been used without detrimental effect to the joints. These dynamic exercises are more effective in increasing muscle strength, range of motion, and physical capacity [25]. However, high-intensity weight-bearing exercises have been shown to accelerate joint destruction in individuals with preexisting extensive large-joint damage from rheumatoid arthritis [26]. Thus the exercise prescription must be appropriately tailored to the degree of disease present in each patient. The motivation and encouragement provided by the physician and therapist should not be underestimated. In one study, the communication skills and disease-specific knowledge exhibited by the therapists were most important in managing the patient’s disease. The investigators also identified a need for therapists to have a good understanding of the disease process and to understand the role of a multidisciplinary team in treating the patient [27]. Some therapists may require more professional development to confidently educate and treat this patient population. In another study by O’Brien [28], there was significant improvement in arm function with patients who did home strengthening exercises versus stretching and education alone. Resistance exercise has been shown to be safe and efficacious as it improves isokinetic, static, and grip strength [29]. Community aquatic programs for arthritis help reduce stress on weight-bearing joints and provide some general conditioning [30,31].

Procedures

For monarticular or oligoarticular involvement, local steroid injection may be used when oral medications fail to control joint inflammation. If there is electrodiagnostically confirmed carpal tunnel syndrome, focal steroid injections may be helpful. If the neurophysiologic studies confirm more sensory axonal loss or motor involvement, surgical decompression may be recommended [32]. Ultrasonography is recognized as useful diagnostically, because a skilled examiner can differentiate tendinopathy from bursitis and determine whether there is any entrapment of these structures with movement. The goal of any diagnostic procedure is increase the specificity for the diagnosis. Sonography is dynamic and can be more specific than other diagnostic imaging in the hands of a skilled sonographer [33]. There is increasing use of ultrasonography for needle placement during procedures to ensure injection into the affected joints [34]. The goals of any procedure are to maintain the patient’s functional level, to minimize pain, and to try to prevent more debility from the disease by slowing the progression or treating associated problems that impair function.

Surgery

Orthopedic intervention includes joint reconstruction (arthrodesis) or replacement (arthroplasty) (Fig. 151.5). For hand patients with low-demand activities, arthroplasty may be helpful, whereas more active patients may do better with arthrodesis [35]. For patients with involvement of larger joints, arthroplasty can significantly improve one’s activity level and lifestyle. Some patients may require tendon repair or synovectomy. Any surgical procedure should take into consideration the functionality of the entire upper or lower extremity [36]. Patients with suspected or confirmed cervical spine involvement will need special consideration and handling during intubation for anesthesia (Fig.151.6). Surgical cervical spine stabilization may be considered if the patient has neurologic symptoms.

Potential Disease Complications

The most common complication is joint destruction with subsequent decreased functional use of affected joints. Neuropathy may be due to entrapment, pressure, or deposition of amyloid. Cervical instability can lead to myelopathy. Irregular bone edges may result in tendon rupture. Nodules may break down and ulcerate. Skin ulcerations may also occur in pressure points in the immobilized patient. The kidneys and gastrointestinal tract may be sites of deposition in patients who develop secondary amyloidosis. Scleritis may result in scleromalacia. As previously mentioned, cardiovascular disease is almost always present in aggressive or untreated cases.

Potential Treatment Complications

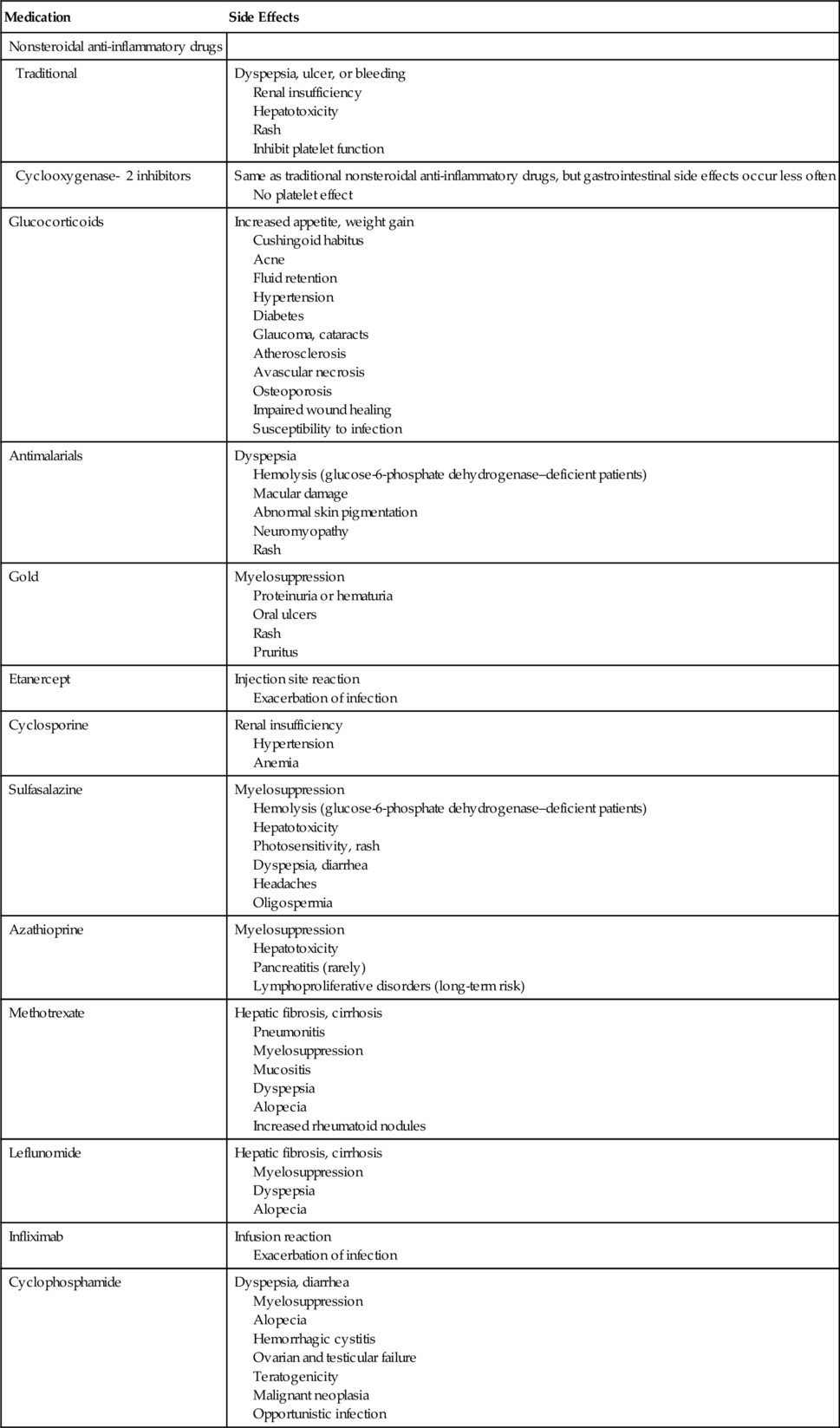

Medication side effects vary according to the drug (Table 151.3) [16].

Overly aggressive physical or occupational therapy can cause increased joint inflammation, joint deformity, and pain.