CASE 15 Transplant Vasculopathy

Case presentation

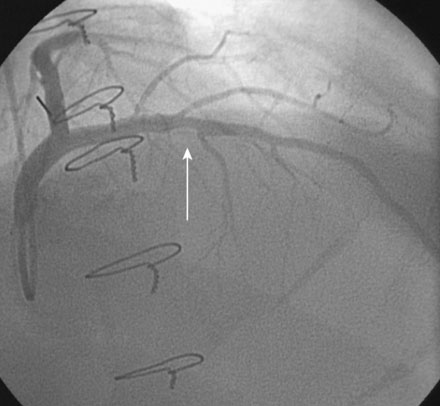

A 61-year-old man underwent orthotopic heart transplantation 16 years ago for ischemic cardiomyopathy. He now presents for his annual routine right and left heart catheterization, coronary angiogram, and endomyocardial biopsy. A coronary angiogram performed 1 year earlier showed only mild atheromatous disease in the left anterior descending artery without significant luminal narrowing (Figure 15-1). He remains free of all cardiac symptoms including chest pain, dyspnea, exercise intolerance, syncope, or edema. Other pertinent medical history includes peripheral vascular disease treated with an aortobifemoral bypass, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and mild renal insufficiency with a baseline creatinine of 1.4 mg/dL. Medications include simvastatin, diltiazem, azathioprine, cyclosporine, and aspirin. Recent lipid analysis found an LDL of 103 mg/dL and an HDL of 41 mg/dL.

Cardiac catheterization

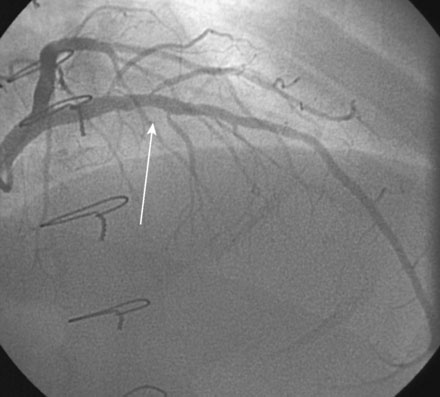

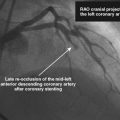

The right heart pressures were normal. Selective coronary angiography revealed nonobstructive, mild atheromatous disease in the right coronary artery, unchanged from the previous year (Figure 15-2). The left coronary artery showed progression of the lesion in the left anterior descending artery. This lesion now appeared to significantly narrow the lumen (Figure 15-3 and Video 15-1). The circumflex appeared angiographically normal.

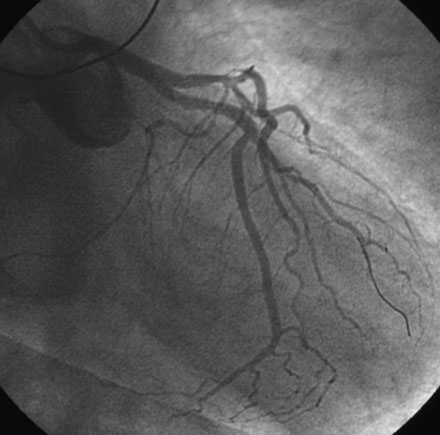

Based on the observed progression of his disease and the known natural history of transplant-associated vasculopathy, his transplant cardiologist recommended percutaneous intervention of the left anterior descending artery. Using an intravenous bolus and infusion of bivalirudin followed by an oral load of 600 mg of clopidogrel, the operator inserted a 3.5 mm diameter by 16 mm long paclitaxel-eluting stent, and postdilated the stent with a 4.0 mm diameter by 9 mm long noncompliant balloon, achieving an excellent angiographic result (Figure 15-4 and Video 15-2). He had no complications and was observed overnight.

Postprocedural course

He was discharged the next morning with the addition of long term clopidogrel to his medical regimen. He remained symptom- and event-free during follow-up. A routine coronary angiogram performed 1 year later found no progression of the disease in the right coronary artery and a widely patent stent in the left anterior descending artery without evidence of restenosis (Figure 15-5).

Discussion

Cardiac allograft vasculopathy is a progressive atherosclerotic condition that limits long-term survival after cardiac transplantation. Angiographic evidence of allograft vasculopathy is observed in nearly half of patients within 8 to 10 years of transplant. The prevalence is even higher when intravascular ultrasound, a more sensitive method for detecting atherosclerosis, is used.1,2 The pathophysiology is complex and related to both immune and nonspecific insults and has been extensively reviewed elsewhere.1,3 Often described as a diffuse obliterative process affecting the distal vasculature, it may also manifest as focal lesions in proximal vessels, such as the one presented in this case.4

Great effort has been invested in prevention, but only statin therapy reliably lowers the rate of development of transplant-associated vasculopathy.5 Once the disease is angiographically evident, it progresses rapidly. Retransplantation is the only definitive treatment, but is not practical due to the limited donor pool and is associated with poor long-term survival.

Revascularization is a palliative technique that has not been convincingly shown to change the natural history of the disease or extend the life of the allograft. Coronary bypass surgery can be performed, but is often not feasible because of poor distal targets from the diffuse obliterative disease; it is also associated with a high procedural mortality. Based on limited case series, percutaneous revascularization techniques appear safe and feasible. The high procedural success rates are tempered by excessive restenosis rates, particularly following balloon angioplasty and bare-metal stents.6 Although there is no randomized comparison between bare-metal and drug-eluting stents, small series suggest lower restenosis rates with drug-eluting stents.6,7

1. Schmauss D., Weis M. Cardiac allograft vasculopathy. Recent developments. Circulation. 2008;117:2131-2141.

2. Tuzcu E.M., DeFranco A.C., Goormastic M., et al. Dichotomous pattern of coronary atherosclerosis 1 to 9 years after transplantation: insights from systematic intravascular ultrasound imaging. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1996;27:839-846.

3. Mehra M.R. Contemporary concepts in prevention and treatment of cardiac allograft vasculopathy. Am J Transplant. 2006;6:1248-1256.

4. Gao S.Z., Alderman E.L., Schroeder J.S., Silverman J.F., Hunt S.A. Accelerated coronary vascular disease in the heart transplant patient: coronary arteriographic findings. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1988;12:334-340.

5. Wenke K., Meiser B., Thiery J., et al. Simvastatin initiated early after heart transplantation: 8-year prospective experience. Circulation. 2003;107:93-97.

6. Tanaka K., Li H., Curran P.J., Takano Y., Arbit B., Currier J.W., Yeatman L.A., Kobashigawa J.A., Tobis J.M. Usefulness and safety of percutaneous coronary interventions for cardiac transplant vasculopathy. Am J Cardiol. 2006;97:1192-1197.

7. Lee M.S., Kobashigawa J., Tobis J. Comparison of percutaneous coronary intervention with bare-metal and drug-eluting stents for cardiac allograft vasculopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol Intv. 2008;1:710-715.