CHAPTER 147

Postconcussion Symptoms

Mel B. Glenn, MD; Seth D. Herman, MD

Definition

Postconcussion symptoms are a set of symptoms commonly seen after concussion. The term concussion is generally used as a synonym for mild traumatic brain injury (mTBI). A number of definitions with varying lower and upper limits of severity for diagnosis have been proposed [1]. One commonly used definition of mTBI is a traumatically induced physiologic disruption of brain function, manifested by at least one of the following:

• any period of loss of consciousness;

• any loss of memory for events immediately before or after the accident;

• any alteration in mental state at the time of the accident (e.g., feeling dazed, disoriented, or confused); and

• focal neurologic deficits, which may or may not be transient;

but in which the severity of injury does not exceed the following:

• loss of consciousness of approximately 30 minutes or less;

• after 30 minutes, an initial Glasgow Coma Scale score of 13-15; and

• post-traumatic amnesia not longer than 24 hours [1].

“Complicated” mTBI is characterized by the addition of intracranial abnormalities on computed tomography (CT) scan on the day of injury [2].

There are also several classification systems [3]. Table 147.1 presents a classification established by the American Academy of Neurology [4].

Table 147.1

American Academy of Neurology Classification of Mild Traumatic Brain Injury

| Grade of Concussion | Characteristics |

| Grade 1 | Transient confusion All symptoms < 15 minutes and Mental status changes < 15 minutes |

| Grade 2 | Transient confusion Any symptoms > 15 minutes and/or Mental status changes > 15 minutes |

| Grade 3a | Brief loss of consciousness (seconds) |

| Grade 3b | Prolonged loss of consciousness (minutes) |

From Practice parameter: the management of concussion in sports (summary statement). Report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee. Neurology 1997;48:581-585.

Bazarian and colleagues [5] reported the incidence of emergency department visits for mTBI to be 503 per 100,000, which is about 1.4 million emergency department visits for mTBI in the United States per year. This is similar to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimate of 1.375 million [6]. However, the true numbers are probably considerably higher, given that a large percentage of people do not seek hospital treatment.

Symptoms

The most common postconcussion symptoms are headache, dizziness (often vertiginous) or poor balance, forgetfulness, difficulty in learning or remembering, difficulty in concentrating, slowed thinking, hypersomnolence, fatigue, insomnia, depression, anxiety, irritability, sensitivity to noise and light, and visual problems [7,8]. The most commonly used instrument for assessing the number and severity of postconcussion symptoms is the Rivermead Post-Concussion Symptoms Questionnaire, which has been found to have adequate divergent validity and reliability [9–11]. Criteria for “postconcussion syndrome” have been established by the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision [12], the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision [13], and the fourth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders [14]. However, symptoms may be present in a wide variety of both limited and extensive constellations and as such do not constitute a true syndrome [7,8]. There may be a lag of days or weeks between the concussion and the patient’s first complaints, and some related phenomena, such as depression, may not become manifest until months after the initial injury. Although these symptoms can be seen with any severity of injury, they are often most pronounced in the context of mTBI. Over time, most people make a complete clinical recovery [11]. Although some authors have estimated that less than 5% still have symptoms 1 year after injury [15], studies vary considerably in this regard [16–18]. The prevalence of postconcussion symptoms is relatively high in healthy populations [15]; in people with whiplash and other painful conditions, depression, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and acute stress; and in people litigating non-head injuries [19]. Nevertheless, one study found a difference of 31% between those who had mTBI and a non–head-injured control group with orthopedic injuries with respect to the number who had three or more symptoms 1 year after injury. However, these differences were significant only among those who were married and those who had higher levels of education [17].

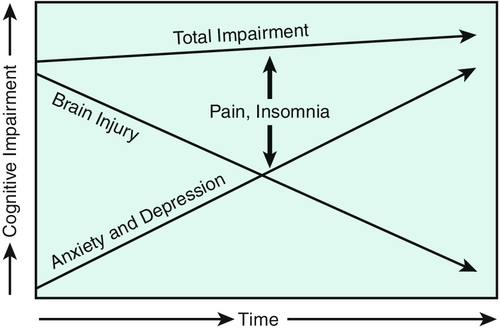

The etiology of postconcussion symptoms is often multifactorial, and much of it is still not well understood. The usual inciting factors are mTBI with residual impairment of cognition, whiplash or other soft tissue injury to the head and neck, and at times disruption of the vestibular apparatus or central vestibular insult. Problems with attention, forgetfulness, and fatigue coupled with the frequent development of headaches, insomnia, and vertigo often lead to considerable anxiety and depression and a “shaken sense of self” [20]. In those who have persistent problems, a complex of symptoms often feed one on the other [7], exacerbating the cognitive impairment, which may then take on a life of its own even as the underlying brain injury continues to recover [20,21]. A common scenario is one in which pain, anxiety (including, at times, PTSD), and depression contribute to insomnia, which in turn exacerbates headaches, and all of these symptoms contribute to cognitive impairment [11]. Early on, as the symptoms attributable to brain injury gradually improve, the patient may not experience any cognitive improvement because other factors are driving these symptoms. The lack of improvement often increases the patient’s anxiety and can bring about depressive feelings. A vicious circle ensues (Fig. 147.1). Difficulty in concentrating can also result in headaches, which exacerbates the complex. PTSD should be suspected in individuals who have reexperiences of the original injury (“flashbacks”), avoidance of situations similar to that which caused the injury (e.g., riding in a car), a feeling of emotional “numbness,” and hyperarousal. There are high prevalence rates of PTSD, mTBI, and their co-occurrence in recently deployed soldiers [5].

There is evidence to suggest that persistence of symptoms is associated with a high number of early symptoms: acute headache, multiple painful areas, nausea, dizziness, or balance problems; early impaired memory; intoxication at the time of injury; intracranial lesions on the day of injury CT scan; loss of white matter integrity on diffusion tensor imaging; preexisting social, psychological, and vocational difficulties; lack of social support; less education; lower socioeconomic status; age older than 40 years; being married; female gender; current student status; litigation or compensation; being out of work secondary to injury; motor vehicle crash as cause of injury; lack of fault for a collision; preexisting physical impairment; APOε4 genotype; and preexisting brain (including prior mTBI) and other neurologic problems. Studies vary with respect to some of these findings [8,11,15,22–26]. However, the total body of evidence regarding the causes of poor outcome after mTBI suggests a complex interaction among biologic, psychological, and social factors, with different factors varying in significance by the individual [27]. It is notable that people with mTBI have been found to underestimate the frequency of symptoms that they had before the injury, demonstrating a bias toward attributing current symptoms to the mTBI (“good old days bias”) [17].

Most authors have not defined a particular time frame for the designation of “persistent” postconcussion symptoms; those who have done so have used 3 months as a cutoff [16,28]. The question of persistence of cognitive impairment after mTBI has been a subject of considerable controversy. Most controlled studies and meta-analyses indicate that cognitive deficits found on neuropsychological testing resolve within 3 months of mTBI, with the notable exception of complicated mTBI [2,29]. Most studies have been done with relatively young people, often athletes. Some studies have found subtle differences from controls [30,31] or differences on more demanding tests, such as dual-task performance, months or years after injury [32]. Subtle differences in balance have also been found among college football players who have had one or more concussions compared with those who have not [32]. Athletes who have had multiple concussions have been found to do worse on neuropsychological testing than controls [22,33]. There is a greater prevalence of mild cognitive impairment in later life [34] among professional football players who have had concussions than among those who have not had a concussion. These findings suggest that a single concussion may result in some loss of brain function, possibly subclinical in most people. In addition, individuals who have had one or more concussions months or years ago have been found to have evidence for loss of white matter integrity on diffusion tensor imaging [26] and differences from control subjects on functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) [35] and event-related potentials [32].

Cognition

The patient should be questioned about the inciting event with regard to whether there was a loss of consciousness, loss of anterograde or retrograde memory, other alteration in mental status, or focal neurologic findings. A patient’s subjective feeling of being dazed or confused may or may not reflect actual brain injury. It is common for people to feel dazed because of the emotional shock experienced after an accident. There is often limited or no documentation of the details of the patient’s mental status immediately after the accident, and a clinician must do his or her best to reconstruct the situation largely on the basis of the history given by the patient. The observations of others may help clarify whether the patient was responding slowly or otherwise appeared confused. Emergency medical records should be obtained whenever possible but may or may not reflect the patient’s mental status at the scene of the accident and may not pick up more subtle deficits if only orientation is evaluated.

Headaches

Tension, migraine, cervicogenic (musculoskeletal), and mixed headaches are the most frequent types seen after concussion. Pain from soft tissue injury at the site of impact, occipital neuralgic pain, and dysautonomic cephalgia can be seen as well. The patient should be questioned with respect to severity, quality, location and radiation, date of onset, duration, frequency, exacerbating or ameliorating factors, and frequency of medication use in addition to associated symptoms, such as nausea, vomiting, visual phenomenon, diaphoresis, rhinorrhea, and sensitivity to light and noise [36,37].

Vestibular/Balance Disorder

Vertigo and other illusory motion related to head movement or position as well as impaired balance can be caused by cupulolithiasis or canalithiasis (benign paroxysmal positional vertigo), brainstem injury, migraine-associated vertigo, labyrinthine concussion, or perilymph fistula or may be cervicogenic. Perilymph fistula and labyrinthine concussion are usually associated with hearing loss and tinnitus as well. Nonvertiginous dizziness is not usually directly related to concussion; medication-induced dizziness (e.g., by nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and antidepressants) and other causes should be considered, including psychogenic dizziness [38]. See also Chapter 8.

Sleep

A history of fatigue or daytime sleepiness should suggest the possibility of a sleep disorder. Delayed sleep phase syndrome and disrupted sleep-wake cycles can usually be diagnosed by history. Being overweight or obese or heavy snoring suggests obstructive sleep apnea. Difficulty in falling asleep and maintaining sleep can be determined by history [11].

Other

The physician’s history of the events surrounding the initial accident should also include exploration of other associated injuries, seizure, vomiting, and drug or alcohol intoxication. A preinjury medical, social, psychological, vocational, and educational history should be obtained, including any history of attention deficit disorder or learning disability.

Physical Examination

Cognition

The examination of the individual with postconcussion symptoms will often elicit problems with attention, memory, and executive function on mental status evaluation. Memory problems are most often related to attention deficits or difficulty with retrieval [39]. The contribution of attention, encoding, and retrieval problems to verbal memory can be evaluated with the presentation of a word list followed by immediate recall, recall after 5 minutes, and then a multiple choice recognition task, which provides the structure needed to assist retrieval when information has been encoded. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, which contains subtests that challenge executive function as well as memory and attention, is a useful tool to assess for cognitive impairment, although it has not been studied in traumatic brain injury [40]. However, findings on mental status testing may be normal; more extensive evaluation by neuropsychological testing, including reaction time [31] and continuous performance tasks, may be necessary to reveal the deficits. Findings inconsistent with daily functioning or more severe than would be expected for someone with mTBI indicate that there may be poor effort or other contributing factors [19,41]. See the section on differential diagnosis for potential contributing factors [20].

Psychological

Assessment of affect, demeanor, and behavior may reveal evidence of depression, anxiety, and other psychological characteristics. The Patient Health Questionnaire-9 is one approach to assessing depression. It is a brief questionnaire that mirrors the diagnostic criteria of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (fourth edition) for major depression. It has been found to be valid and reliable in people with traumatic brain injury [42]. The Primary Care PTSD Screen is another useful instrument. Those who screen in for PTSD should then receive a more thorough assessment [43].

Headaches

Examination of the head and neck often elicits restriction of motion, tender points, or trigger points radiating to the head. There may be tenderness at the site of the original head injury and occasionally pain elicited by compression of the occipital nerves [36,37]. See Chapters 102 and 105.

Vestibular/Balance Disorder

During acute vertigo, nystagmus will often be present, generally stronger with peripheral than with central vertigo. As adaptation begins to occur, nystagmus may be seen only with certain maneuvers (e.g., after 20 horizontal head shakes) or may not be seen at all. When benign paroxysmal positional vertigo is the cause, the Hallpike-Dix maneuver is usually positive. This maneuver is performed from the sitting position on a flat surface with the head rotated 45 degrees to either side. The patient is quickly lowered from the sitting to the lying position, until the head, still rotated, is extended over the edge of the examining table. Vertigo is experienced and nystagmus seen after a lag of up to 30 seconds [38]. Neck range of motion and tender points or trigger points should be assessed for contributions from cervicogenic dizziness (see also Chapter 8). Patients with vertigo and other illusory movement may also have balance problems, but impaired balance with difficulty on tandem walk, standing on one leg, hopping, and other maneuvers may be seen without vertigo. The Balance Error Scoring System can provide a quantifiable assessment of balance [11].

Visual

Some patients complain of a feeling of visual disorientation or intermittent blurred vision. The symptoms can be related to a need for changes in refraction, accommodative dysfunction [44], or vascular, vestibular, attentional, or psychological problems. Frequently nothing will be found on routine examination.

Olfactory

The sense of smell may be affected by damage to branches of the olfactory nerve as they pass through the cribriform plate or by focal cortical contusion.

Other cranial nerve testing, muscle strength, cerebellar testing, deep tendon reflexes, plantar stimulation, and sensation are usually normal.

Functional Limitations

The extent to which postconcussion symptoms interfere with function varies with the extent of the associated pathologic process but depends also on the psychological reaction to the postconcussion impairments. The most common consequences of postconcussion symptoms are limitations in home and community living skills or social, academic, or vocational disability. Patients may be forgetful and inattentive, may have difficulty following conversations, and may find crowded, noisy environments difficult to tolerate. Headaches are often exacerbated by attentional demands and other stresses and may themselves contribute to inattentiveness. Vertigo or other illusory motion causes difficulty in tolerating motion, including, for some, moving vehicles, and may be associated with balance problems. Depression, anxiety, and irritability can contribute heavily to functional limitations.

Diagnostic Testing

The brain CT scan is the standard for the acute assessment of intracranial lesions after mTBI [45]. Indications for emergent CT scan include headache, vomiting, loss of consciousness or amnesia, alcohol intoxication, age older than 60 years, post-traumatic seizure, physical evidence of trauma above the clavicles, and current anticoagulant use [45,46]. Although definitive criteria have not been established for those who have had no loss of consciousness, it is probably wise to obtain a CT scan or MRI study for anyone who continues to have frequent headaches, severe lethargy, confusion, or anterograde memory loss or who has focal neurologic findings and has not had any neuroimaging acutely. MRI with susceptibility-weighted imaging is more likely to show microhemorrhage related to diffuse axonal injury [26]. Event-related potentials [32], serum biomarkers (such as S100B [47]), advanced magnetic resonance techniques (such as diffusion tensor imaging [26] and fMRI [35]), and metabolic imaging (such as positron emission tomography, single-photon emission computed tomography, and magnetic resonance spectroscopy [48]) have shown promise but have not yet been studied thoroughly enough to be used routinely to answer clinical questions after mTBI [49].

Cervical spine radiographs should be obtained for patients with significant neck pain shortly after the accident to assess for fracture or subluxation.

Neuropsychological evaluation should be performed if cognitive deficits persist, particularly when rehabilitation therapies are to be pursued. Testing can provide the patient and the treatment team with a more thorough understanding of the patient’s neuropsychological strengths and weaknesses and in some instances can assist with understanding of the interplay between neurocognitive and other psychological contributions to cognitive disturbance. Tests for assessment of malingering and symptom magnification (“effort testing”) can be incorporated when necessary. In one study, people with mTBI for whom financial compensation was available, and who were referred for neuropsychological testing an average of 19.4 months after injury, had a 26.7% failure rate for effort testing (Test of Memory Malingering). Those with better benefits had a higher rate than those with modest benefits [50]. However, symptom magnification does not eliminate the possibility that the person has real cognitive deficits as well. It is useful for sports teams to have their players undergo at least a brief baseline cognitive testing or, if the resources are available, formal neuropsychological testing so that any changes can be identified after the concussion [51]. A history of attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder or learning disability, certain medications or abused substances, depression, anxiety, pain, sleep disorders, malingering, symptom exaggeration, and even expectation of the cognitive effects of mTBI can lower test performance [52]. On the other hand, normal findings on testing do not preclude a more subtle but significant underlying cognitive impairment.

A sleep study (polysomnography) is indicated to rule out sleep apnea and other disorders when excessive daytime sleepiness does not improve despite the absence of sedating medications. The threshold for obtaining polysomnography should be lower for overweight or obese patients or those who snore prominently. When vestibular complaints are prominent or are not improving in the early months after the injury, a thorough vestibular evaluation, including electronystagmography, may be indicated. Audiologic evaluations should be done when hearing loss is suspected or when tinnitus persists [38]. Ophthalmology or optometry evaluation by someone with particular expertise in visual problems related to brain injury should be considered when visual symptoms are present. Although post-traumatic neuroendocrine dysfunction is more commonly found among those with more severe traumatic brain injury, even mTBI may be associated with pituitary dysfunction. Schneider and coworkers [53] found a prevalence of endocrine disorders of 16.8% among patients with mTBI and persistent postconcussion symptoms. Neuroendocrine testing should be considered in individuals with mTBI who have persistent fatigue, cognitive difficulties, behavioral changes, or depression as these can be symptoms of post-traumatic hypopituitarism. Other manifestations include decreased libido, amenorrhea, myopathy, and life-threatening complications such as sodium dysregulation and adrenal crisis [54]. Recommended screening includes serum free thyroxine, thyroid-stimulating hormone, morning cortisol, prolactin, and insulin-like growth factor 1 levels; testosterone concentration in men; and follicle-stimulating hormone concentration in postmenopausal women or premenopausal women with amenorrhea [55].

Treatment

Initial

Treatment will depend on the specific constellation of symptoms and their severity. In general, if the patient is seen in the first few weeks after the injury, the major emphasis should be placed on caring for acute problems with headache, neck pain, and insomnia as these symptoms tend to be more responsive to early treatment than cognitive impairment and dizziness. However, education of the patient and significant others is the most important early intervention. Explanations should integrate the physical, cognitive, and psychological dimensions of the symptoms in as clear and simple a manner as possible. This is no small task, given the diversity of symptoms and possible causes and our limited understanding of postconcussion disorders at this time. Some patients are very sensitive to discussions of psychological etiology and may not return if they believe that this has been overemphasized. The patient’s experience, including the psychological reactions, should be validated and normalized [20]. The patient should be told that improvement is to be expected, and after concussions without high-risk factors (e.g., numerous previous concussions, complicated mTBI), reasonable reassurance should be given that a good recovery is likely without dismissing what the patient is experiencing. Establishing a reasonable expectation for recovery can be helpful in preventing postconcussion symptoms [56,57]. Anticipating the psychological reactions to postconcussion symptoms that occur in some patients allows the patients to recognize these reactions if they begin and leaves the door open for them to seek psychological help. Follow-up should be planned and more extensive counseling provided at the first signs of significant distress. Patients with significant symptoms should be instructed to take time off from work, school, or other taxing activities as the attentional demands and accompanying psychological stresses of attempting to perform under these circumstances can exacerbate the symptoms [23]. All patients should be instructed not to drive for at least the first 24 hours, longer when they have had post-traumatic seizures, slow processing speed, attention deficits, dizziness, and visual or other symptoms that are likely to interfere [11].

Athletes should not go back to competitive sports on the day of injury until they are free of symptoms and have gone through a program of graded exertion symptom free. Those with more severe concussions should move through this program more slowly [51]. Refer to Table 147.2 for guidelines for the stepwise return to sports activities.

Table 147.2

Template for Stepwise Return to Sports

| Stage | Activity | Objective |

| No activity | Symptom-limited physical and cognitive | Rest and recovery |

| Light aerobic exercise | Walking, swimming, or stationary bicycle, keeping intensity less than 70% of maximum predicted heart rate; no resistance training | Modest increase in heart rate |

| Sport-specific exercise | Skating drills in ice hockey, running drills in soccer; no head impact activities | Further increase in heart rate in sport-specific context |

| Noncontact training drills | Progression to more complex training drills (e.g., passing drills in football and ice hockey); may start progressive resistance training | Challenge agility, coordination, and cognitive aspects of sport |

| Full-contact practice | Following medical clearance, participate in normal training activities | Full physical and cognitive challenge; restore confidence and allow coaching staff to assess functional skills |

| Return to play | Normal game play |

Modified from McCrory P, Meeuwisse W, Johnston K, et al. Consensus statement on concussion in sport—the 3rd International Conference on Concussion in Sport held in Zurich, November 2008. PM R 2009;1:406-420.

Severe acute vertigo may require a few days of bed rest [38], but only if it is absolutely necessary. The management of acute neck pain is described in Chapter 6.

Rehabilitation

Cognition

If symptoms persist, patients may benefit from speech or occupational therapy to learn strategies for compensating for problems with arousal, attention, memory, and executive function and, later, training for internal compensation and restoration of cognitive skills [58–61]. The timing of therapies depends on the severity of the disability and the pace of recovery, which can often be determined within the first 3 months after injury. There are no published data on the optimal timing of these interventions, and no specific guidelines are available. Therapies should address the specific functional tasks that the individual faces on a daily basis and may need to include community outings. Foam earplugs or sunglasses can be tried for those sensitive to noise and light, respectively. Paper or electronic memory aids may be helpful. Psychostimulants and dopaminergic drugs (e.g., methylphenidate, amphetamines, atomoxetine, donepezil, modafinil, armodafinil, amantadine) and cholinesterase inhibitors (e.g., donepezil, 5-23 mg daily) that treat attentional and arousal disorders may be useful for reducing the extent of attention deficits and underarousal [62,63]. When sleep apnea is contributing to cognitive problems, positive airway pressure therapy, sleep position changes, or custom dental devices are indicated. Both resistance and aerobic exercises can result in improved cognitive function [64,65]. Exercise may also benefit other postconcussion symptoms when heart rate is kept below the rate that provokes symptoms [66]. There is some evidence to suggest that acupressure may also result in improved cognitive function [67].

Psychological

If symptoms persist beyond a few months, psychological counseling is almost always indicated. Some individuals benefit from learning relaxation techniques and sleep hygiene. Cognitive-behavioral therapy focused on sleep issues can help insomnia [68]. Education of the patient and significant others should continue to emphasize the interaction between the cognitive, psychological, and physical sequelae. It is important that the rehabilitation team communicate on a regular basis for treatment planning and to ensure that all clinicians approach these issues from a common framework so that mixed messages are not delivered to the patient. Support groups are often useful as well and offer an opportunity for further education about the various contributing factors. Cognitive-behavioral therapy can be helpful in concert with other treatments [69] even when symptoms do not seem to be explained by the medical condition [70]. It can target depression, anxiety, insomnia, pain, and probably other postconcussion symptoms as well. Other psychotherapy approaches include acceptance and commitment therapy and self-management, both of which focus on improving daily function rather than on improving symptoms [52]. Family counseling should be offered when there is evidence of significant stress on family members or problem family dynamics.

Depression and anxiety can also be addressed pharmacologically when they are severe and prolonged, contributing to cognitive impairment, or interfering with progress in rehabilitation, usually after or simultaneously with counseling interventions. It is generally best to begin with nonsedating, nonanticholinergic agents, such as the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (e.g., sertraline), to avoid further exacerbation of neuropsychological problems [62]. Cognitive status has been found to improve after treatment with sertraline [71]. Sedating agents, such as trazodone, zolpidem, or eszopiclone, may be necessary for those with significant insomnia [62] if treatment of depression and anxiety and sleep hygiene approaches are not successful. Zolpidem (10 mg at bedtime) can cause cognitive impairment in the morning [72]. Melatonin (0.5-3 mg) can be helpful, especially with delayed sleep phase disorder.

Headaches

Post-traumatic headaches can have a number of different causes and may be multifactorial [21,23,24,36–38]. They are therefore best addressed on multiple levels, with the emphasis depending on the headache type [73]. Treating problems with attention, sleep disorders, and psychological stresses may reduce the tension component of headaches. Relaxation techniques, including electromyographic biofeedback, can be taught. When myofascial pain originating in the neck, upper back, or temporomandibular joints contributes, physical therapy including stretching and strengthening exercises, postural retraining, environmental modification, trigger point massage, modalities, electromyographic biofeedback, or massage should be tried. However, headaches often persist despite these interventions. Trigger point, facet joint, and other injections can be helpful, as can acupuncture and pharmacologic approaches. Patients with temporomandibular joint problems can be treated with myofascial techniques, mouthguards, and exercises.

Those headaches that fit the criteria for migraine headaches may respond to acetaminophen, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, or vasoconstrictive agents commonly used to abort migraine headaches (e.g., sumatriptan). Overuse of these agents can cause rebound headaches. For prophylaxis, anticonvulsants (particularly gabapentin and valproic acid), beta blockers (e.g., propranolol), calcium channel blockers (e.g., verapamil), and antidepressants (e.g., amitriptyline, nortriptyline, fluoxetine, venlafaxine) can be helpful. Topiramate often provides some relief but causes too much cognitive decline to be used as a first-line drug [74]. However, if it relieves frequent headaches that themselves are causing cognitive impairment, the tradeoff may be favorable. Tension headaches may respond to some of these agents as well, although not to calcium channel blockers. Injection of local anesthetics or corticosteroids can be considered for greater or lesser occipital neuralgia that does not respond to more conservative approaches. Injection should be done at the site along the nerve that replicates the headache when it is palpated [36,73] (see Chapter 102).

Vestibular/Balance Disorder

When vestibular symptoms persist beyond 3 months, vestibular rehabilitation may both encourage central nervous system accommodation under controlled circumstances and assist the patient in learning compensatory strategies [75]. Canalith repositioning maneuvers may bring relief from benign paroxysmal positional vertigo by displacing and dispersing calcium stones [76]. Suppressive medications (e.g., clonazepam, scopolamine, meclizine) should be used judiciously, if at all, when other approaches have failed [38]. The evidence for their efficacy is not strong, and they can cause worsening of problems with attention and memory. Frequent vertigo or other illusory motion in people with migraine headaches (migraine-associated vertigo) is best treated preventively with tricyclic antidepressants, beta blockers, or calcium channel blockers and vestibular rehabilitation. Cervicogenic dizziness can be treated by addressing the underlying cervical musculoskeletal problems (see Chapter 8). Physical therapy can help improve balance.

Vocational

The extent to which an employer or academic institution is supportive after mTBI can be crucial to successful return to work for those with persistent postconcussion symptoms. Vocational counselors can facilitate communication between the patient and the workplace. Therapies should attempt to simulate workplace tasks. A gradual return to work can ease the transition [20].

Procedures

Procedures are discussed in the preceding sections.

Surgery

There is little that can be done surgically to manage postconcussion disorders.

Potential Disease Complications

Persistence of postconcussion symptoms beyond a few months is a possible outcome. Individuals who sustain a second concussion while still symptomatic from a recent concussion may be susceptible to cerebral edema and dangerous increases in intracranial pressure (“second impact syndrome”) [77], although some have questioned the existence of such a syndrome [78]. Multiple concussions, even after apparent clinical recovery from earlier episodes, can result in cumulative brain injury with permanent cognitive impairment or even dementia, at times with parkinsonian motor features, depression, or aggression in later life. Unique patterns of pathologic findings consistent with chronic traumatic encephalopathy have been found on autopsy in 68 of 85 people who have had multiple concussions who donated their brains. Most were boxers, football and hockey players, or military veterans. Most had developed cognitive impairment, sometimes associated with depression and suicide [79,80]. The incidence of chronic traumatic encephalopathy is unknown. Athletes and their parents (in youth) may want to discontinue involvement in high-risk sports after one or more concussions or may want to avoid such sports altogether. Caution must be exercised by those responsible for returning athletes to play.

Potential Treatment Complications

Those treating the patient with postconcussion symptoms may contribute to the persistence of symptoms either by overemphasizing the role of brain injury in causing symptoms with another etiology or, conversely, by overemphasizing psychological factors when brain injury and other physiologic variables are prominent [20,23]. There is often a fine line to be walked, and each patient must be approached individually in this regard, although there are few data available to guide the clinician.

Some of the complications related to medications can appear paradoxical. The frequent use of analgesics (nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, acetaminophen, and narcotics) can cause rebound headaches, as can the too frequent use of ergotamine and the “triptans.” Although they are generally well tolerated, psychostimulants and dopaminergic agents can lead to sedation, worsening attention, irritability, or psychosis. There are myriad other complications possible from the use of the medications mentioned.