CHAPTER 146

Postpoliomyelitis Syndrome

Definition

Poliomyelitis, also referred to as infantile paralysis, has a special history among infectious diseases. During the first half of the 20th century, there were major epidemics throughout the world. As a viral infection, caused by an RNA virus, it affected mainly children and countries in the Western world with good hygienic and sanitary standards. This occurred when other infectious diseases were being successfully prevented. At the end of the 1940s, several research discoveries led to a better understanding of poliovirus and opened up new opportunities for the manufacture of vaccine. The American organization the March of Dimes invested large sums of money, and the American researcher Jonas Salk started to develop a vaccine, which in 1954 was shown to be effective. General vaccination began in 1956 in the United States and shortly thereafter in other parts of the Western world. This rapidly led to a large reduction in the number of polio cases. In 1988, the World Health Organization decided to try to eradicate polio from the world. The campaign has been highly successful, and there are now only a few countries in Africa (Nigeria) and Asia (mainly Pakistan and Afghanistan) where the virus still exists. The original goal was that polio should be totally eliminated by 2000, but this deadline has been postponed repeatedly. Today, fewer than a thousand new cases are being reported annually.

It is well known that many polio survivors later in life develop new symptoms, referred to as poliomyelitis sequelae, late effects of polio, or just post-polio. Although sequelae of prior polio have been known since the end of the 19th century, it was not until the early1980s that researchers came to agree on the term postpoliomyelitis syndrome (PPS) to describe the various symptoms that polio survivors may perceive. As there are no accurate statistics describing the number of people being affected by polio, we have no clear account of the number living with PPS. The figures in the literature vary, mostly depending on the definitions used, but it is generally agreed that around 60% of those who initially had paralytic polio will develop PPS [1]. In the United States, it is estimated that more than 1 million survivors of polio live in the country; in the European Union (with a population of approximately 500 million inhabitants), the number is approximated to 600,000 polio survivors. With many young polio survivors in Africa and Asia, it is estimated that up to 10 million people around the world will need health care and rehabilitation during the next decades as a result of their poliomyelitis infection. This makes PPS one of the most common neuromuscular conditions and a challenge to rehabilitation professionals.

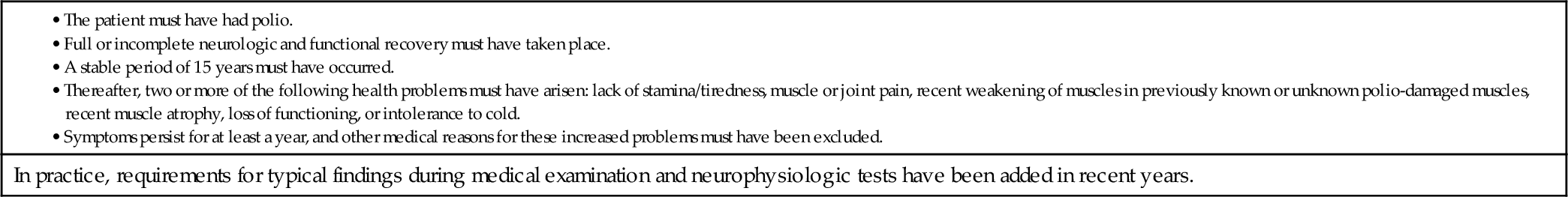

PPS is a neurologic disorder characterized by a collection of symptoms occurring decades after the initial paralytic polio. There are different definitions of PPS, but all are more or less based on the original description by Halstead and Rossi in 1985 and consist of five diagnostic criteria (Table 146.1) [2]. At the March of Dimes international conference on PPS in 2000, diagnostic criteria were recommended, including a criterion that symptoms should persist for at least 1 year [3]. Individuals with prior polio may perceive a number of new symptoms, but the three most common are new muscle weakness, fatigue (muscle as well as generalized), and pain from muscles and joints (at rest and during activities). Other, less frequently occurring but equally disabling symptoms are respiratory problems, swallowing problems, and cold intolerance [4,5].

Table 146.1

Diagnostic Criteria for Postpoliomyelitis Syndrome

• The patient must have had polio.

• Full or incomplete neurologic and functional recovery must have taken place.

• A stable period of 15 years must have occurred.

• Thereafter, two or more of the following health problems must have arisen: lack of stamina/tiredness, muscle or joint pain, recent weakening of muscles in previously known or unknown polio-damaged muscles, recent muscle atrophy, loss of functioning, or intolerance to cold.

• Symptoms persist for at least a year, and other medical reasons for these increased problems must have been excluded.

In practice, requirements for typical findings during medical examination and neurophysiologic tests have been added in recent years.

The cause of PPS is not entirely clear, but it is generally agreed that the new symptoms (muscle weakness and fatigue) are due to a distal degeneration of axons in greatly enlarged motor units that develop during recovery after the acute paralytic polio [5]. After the initial paralysis, motor units are enlarged as a compensatory mechanism. These enlarged motor units undergo a continuous remodeling, and at the age of around 50 years, people start to suffer from the “normal” age-related loss of motor neurons [6]. This process of denervation and reinnervation could be accelerated in PPS owing to a premature dropout of motor neurons caused by neuronal damage from the initial infection, increased metabolic demand in the enlarged motor units, or overuse. The loss of whole, enlarged motor units without reinnervation would also contribute and lead to a progressive dropout of muscle fibers. Other reasons underlying PPS have been discussed during the past decades, such as persistent poliovirus infection; overuse weakness due to transition in contractile properties and firing frequency; weight gain; and combined effects of muscle overuse, disuse, and weight gain. On the basis of recent findings of raised concentrations of cytokines in the cerebrospinal fluid, an inflammatory process might also be present as part of PPS [7]. This has led to the development of new treatment strategies that potentially could be beneficial for people with PPS (see the section on treatment).

Regardless of the underlying pathophysiologic mechanisms of PPS, it is a condition that is highly suitable for physicians in physical medicine and rehabilitation. There is no treatment that can cure PPS or any medication that can clearly delay its progression. However, those who have PPS can benefit from taking part in an interdisciplinary comprehensive goal-oriented rehabilitation program to reduce the consequences of the symptoms and the disability that these symptoms impose on their lives [8–10].

Symptoms

Weakness

Muscle weakness typically occurs in muscles involved during the acute infection but may also be experienced in muscles that were not clinically paralyzed originally. There is an association between the initial weakness and weakness occurring later in life. The greater the initial paralysis, the greater is the PPS-related weakness. Most people start to perceive the new weakness around the age of 50 years; however, the progression of strength losses is usually slow, with an approximate annual loss of 2% to 4% [11]. A history of more rapid progression of muscle weakness during weeks or months could indicate an alternative diagnosis, such as myopathy (e.g., polymyositis, thyroid myopathy), peripheral nerve disorders, or motor neuron disorder (e.g., amyotrophic lateral sclerosis), and should require a thorough investigation.

Fatigue

Fatigue in PPS can be either of muscle origin or more generalized. Muscle fatigue is commonly reported by people with PPS and is characterized by the inability to maintain muscle force. Muscle fatigue is linked to muscle weakness and muscle atrophy, and those with more pronounced muscle weakness also experience more muscle fatigue. Fatigue can also be described as more generalized and of central origin. This type of fatigue can be perceived as severe and persist for several years. It has been found to be associated with reduced physical functioning, increased body pain, reduced sleep quality, and more psychological distress [12]. Typically, this generalized fatigue is described as an influenza-like exhaustion that is often related to the amount of activities performed. Polio survivors usually feel fairly refreshed in the morning and become more fatigued as the day goes on. Some may even complain that they “hit a wall,” sometimes experiencing an almost paralyzing tiredness, and just have to lie down and rest, something that usually relieves the fatigue. It is not unusual for people who have had severe meningitis as part of their acute polio to experience this type of fatigue. In addition, polio survivors who describe a fairly prominent fatigue can also complain about cognitive problems, such as impaired concentration and memory difficulties. Sleep disturbance, which is also reported in polio survivors, can exacerbate general fatigue. As fatigue is an unspecific symptom, commonly occurring in other disorders, alternative diagnoses should be ruled out (e.g., depression, thyroid dysfunction, anemia, other inflammatory diseases, or vitamin B12 deficiency).

Pain

Pain is common among people with PPS and often the symptom that drives them to seek medical help. It has been shown that 50% to 90% of those with PPS experience pain. Pain is common in the shoulders, lower back, legs, and hips and is usually most pronounced in the legs. It is associated with depression and fatigue [13] and can also affect sleep. Not everyone experiences pain, however, and many suffer from mild or no pain. In general, though, increasing pain is related to a lower perceived life satisfaction [14]. Pain can emanate from a joint, a muscle, ligaments, tendons or tendon sheaths, muscle and tendon insertions, and bursae close to a joint. The reason for this is usually the weakness that occurs as a result of muscle atrophy in PPS, which leads to muscle imbalance, stress, and overload and incorrect posture. Pain in PPS can be aching, burning, or cramping in the muscles. Joint pain commonly occurs as a result of the gradual development of osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis after polio can affect joints in parts of the body with muscle weakness resulting from polio but also affects parts of the body not affected by polio because of compensatory overload. Osteoarthritis usually occurs in hip, knee, and foot joints. Typical symptoms are pain under strain, but pain at rest is also common.

Respiratory Problems

During the initial polio infection, breathing could be affected as a result of paralyzed respiratory muscles. This was treated with a ventilator for a longer or shorter time, and some have used a ventilator ever since their polio infection, whereas most improved and managed without it. These people may later in life experience new weakness in their respiratory muscles that can lead to an inability to maintain normal carbon dioxide levels in the blood because of reduced breathing volumes. This so-called underventilation is exacerbated by obesity and worsened by other restrictive lung diseases. However, respiratory problems usually occur in less than 10% of those with PPS. People with PPS-related underventilation can complain of morning headache, daytime tiredness, problems with concentration, restless sleep, waking up several times, nightmares, difficulty getting up in the morning, and increased breathlessness during and after exertion.

Swallowing

Swallowing problems occur only in those who had “bulbar” poliomyelitis that affected the swallowing muscles during the initial infection. Usual complaints are feelings of choking, gagging or coughing, and irritation in the throat or a feeling of a lump in the throat. Some people will also complain of voice problems, especially dysphonia [15].

Cold Intolerance

Cold intolerance is a feeling of coldness in the arms and legs and a general inability to thermoregulate. Cold intolerance may be caused by damage to the part of the brain that regulates body temperature, effects on nerves to arms and legs, or reduced muscle mass. It may also be exacerbated by other medical conditions, such as peripheral vascular disease.

Physical Examination

The findings during a clinical, musculoskeletal, and neurologic examination should support the diagnosis of a lower motor neuron disease process. This includes absent or diminished reflexes, decreased muscle tone, and atrophy (symmetric or asymmetric) and weakness of the muscles in the limbs or trunk. Sensory deficits are not part of PPS, but median and ulnar nerve entrapments are common in polio survivors; therefore, it is important to search for symptoms and signs of sensory disturbances in the hands.

Biomechanical symptoms and signs may also occur from musculoskeletal abnormalities in the lower extremities. This, in turn, is a result of contractures due to muscle weakness (hip and ankle), weakness of the quadriceps causing genu recurvatum at the knee, and reduced joint range of motion without apparent contributing weakness (common in the cervical spine and shoulders). Leg length discrepancies are common and may lead to scoliosis and kyphosis and pain from the spinal column.

Manual muscle testing is a quick and useful assessment of function. However, the occurrence and distribution of muscle weakness, as a hallmark of PPS, can be anything from obvious to subtle. It is therefore not always possible to rule out PPS solely by a clinical examination of muscle strength.

Visual assessment of gait and gait disturbances is a starting point for more mechanistic evaluations. Also, specific areas of the body that are reported as painful should be examined. Seating posture, turning, rising from a chair, and stair climbing are specific movements that can be affected, leading to pain, and may require interventions and corrections.

Fatigue is a common symptom and may be associated with other disorders. Therefore it is important to detect possible signs and symptoms of, for example, depression and sleep disorders. Respiratory problems should also be ruled out by a general physical examination complemented by a basic spirometer examination. Assessment of peripheral pulses and edema is also important.

Functional Limitations

Symptoms occurring as part of PPS can affect a person’s ability to perform daily tasks, such as dressing, feeding, and grooming, as well as domestic life activities, such as managing one’s household, cooking, cleaning, shopping, and participating in leisure activities. This is partly due to a reduced walking ability, including stair climbing, walking shorter and longer distances, and getting in and out of a car. It is also known that these limitations in activities of daily living can affect people with PPS, who may face a variety of challenges related to their participation, which in turn may have an impact on their autonomy and, ultimately, their life satisfaction. Areas that can be affected are family life, social roles, autonomy indoors and outdoors, work, and education [16].

PPS-related muscle and generalized fatigue as well as muscle weakness, muscle and joint pain, and breathing problems could limit the ability to perform usual daily activities, particularly activities that require some physical endurance. This, in turn, can contribute to a general deconditioning, which can cause even greater breathing problems and decreased endurance. It is therefore important to observe signs of a general reduction in physical activity, taking into account all types of daily activities, and to implement a variety of rehabilitation interventions that break this obvious vicious circle.

Diagnostic Studies

Weakness

As part of the routine clinical examination and verification of prior polio, electrodiagnostic studies, including electromyography (EMG) and nerve conduction studies, are highly recommended. Concentric needle EMG is performed to assess the distribution of neuromuscular changes and the degree of changes and also to rule out other neuromuscular diseases. On concentric needle EMG, motor unit action potentials in the limbs previously affected with paralytic polio are abnormally enlarged and polyphasic in configuration, and there is a decreased recruitment secondary to a reduction in the number of motor units available for activation during voluntary muscle contraction [1]. In many cases, EMG may be the only way to determine that signs of PPS are present.

To assess muscle weakness, as part of the routine clinical examination and in planning of appropriate interventions and evaluation, strength testing can be performed. Muscle strength can be assessed manually, with a hand-held dynamometer or with more sophisticated equipment, such as an isokinetic dynamometer. For research purposes, isokinetic dynamometers have been commonly used and are found to be both valid and reliable [17].

If it is clinically needed to establish an alternative or additional diagnosis, imaging of the spine (e.g., magnetic resonance imaging) can help evaluate whether a myelopathy or radiculopathy is present. Useful laboratory studies may include thyroid function studies to rule out thyroid myopathy and muscle enzymes, which can be mildly elevated in PPS.

Fatigue

Persons who experience generalized fatigue should be examined for an alternative diagnosis, for example, anemia, thyroid dysfunction, depression, sleep disorders, and respiratory problems. Other chronic conditions, such as congestive heart failure, diabetes, and chronic infections, can also contribute to fatigue and should lead to appropriate workup. In addition, cancer and other serious malignant diagnoses should also be ruled out.

Pain

For the underlying causes of pain to be understood, various diagnostic procedures are commonly performed, such as blood tests and plain radiographs of the spine and painful joints. Upper extremity neuropathies, such as carpal tunnel syndrome, should be considered and ruled out with electrodiagnostic studies.

Pain in PPS is of nociceptive origin. When pain is of neurogenic origin, alternative diagnoses should be considered, and magnetic resonance imaging and computed tomography can be performed. In rare cases, pain can also occur in persons who have had polio without paralysis or muscle weakness. Last but not least, pain can be due to reasons that are not related to PPS, and it is important that this is also considered.

Respiratory Problems

Respiratory problems can be initially evaluated by a baseline pulmonary function test with a portable desktop spirometer. When a reduced pulmonary function is found, a more thorough investigation with chest radiography and laboratory studies (e.g., arterial blood gas analysis) may be needed, and referral to a pulmonary specialist is recommended.

Swallowing Problems

Swallowing disorders can be diagnosed by imaging studies. A functional endoscopic evaluation of swallowing is most commonly performed.

Cold Intolerance

Cold intolerance can result from several factors, but diagnostic studies are generally not performed unless an alternative diagnosis (e.g., peripheral vascular disease) is suspected.

Treatment

Initial

Weakness

There is yet no treatment that can cure PPS and restore muscle strength. In a series of investigations, different medications (pyridostigmine, amantadine, prednisone, Q10) have been tested, but none has proved beneficial with regard to muscle weakness [18]. On the basis of the notion of an inflammatory process in the central nervous system of patients with PPS, intravenous immune globulin has been tested. In two larger randomized controlled trials, variable effects on muscle strength, pain, physical activity, and quality of life have been described [19,20]. The effect on muscle strength is, however, generally small and within the limits of random variability that would be seen from just repeated measurements [17]. However, the effect on other variables is more prominent. One clinically uncontrolled study showed that two thirds of 45 patients with PPS and pain reported a decrease on the visual analog scale for pain after treatment and 40% reported a decrease of more than 20 points [21]. A follow-up study of 41 patients [22] from the previous treatment trial [19] showed that scores of the physical component of the Short Form 36 (bodily pain and vitality), the visual analog scale for pain, and the 6-minute walk test were significantly better at 1 year compared with baseline and control subjects. These findings encourage further controlled trials to more firmly establish whether this treatment should be used in PPS.

Fatigue

Fatigue is managed by a multimodal approach. Primarily, any medical condition that may be contributing to it should be treated. Sleep disorders, depression, and other causes should be appropriately treated. Proper sleep hygiene is important (e.g., regular bedtimes, avoidance of caffeine late in the day); depression can be treated with medication or counseling or both. It is also important to address a person’s daily activities; various fatigue management interventions, including pacing and taking rest breaks during the day, can be taught. The use of medication to treat fatigue has not been highly successful. Intravenous immune globulin has shown some promising results on fatigue and vitality in subgroups of fatigued patients with PPS [23]. More recently, modafinil has been used to treat fatigue pharmacologically; in more controlled studies, the results have not been particularly encouraging [24], whereas in clinical practice and individual cases, the medication may have an effect. The dose usually starts at 100 mg orally every morning and may be increased to 200 mg daily, 100 mg in the morning and 100 mg at lunchtime.

Pain

Treatment of pain should always start with a thorough analysis of the underlying cause and thereafter selection of appropriate interventions. Treatment of joint pain consists mainly of movement training (e.g., pool exercise) in combination with mobility aids, other aids, or orthotic devices. Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation, acupuncture, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and cortisone injections are other alternatives. Other medications, such as paracetamol and tramadol, can also be prescribed. In severe cases of osteoarthritis, joint replacements are necessary, which may then eliminate the pain completely.

Pain near joints (in tendons and ligaments) is usually due to a continuous overload as a result of muscle weakness. Polio survivors often need mobility aids to relieve this pain when they walk, stand, or engage in other activities. It is also important that they be given information on the importance of reducing the load on their bodies. Activity-related muscle pain is often caused by overuse of the weakened musculature. The most important part is to focus on the reason for the muscle pain. As it is often due to overuse of muscles, the person with PPS needs to understand this so that he or she can make necessary lifestyle changes. This is combined with the prescription of mobility aids to reduce overload during various activities, the provision of information about changed activity patterns, the correction of a sitting position, and the prescription of orthotic devices. Normally, pain is reduced when the load is reduced, but if the overuse continues, the pain can become more lasting and spread to the whole body. Postpoliomyelitis myalgias can be treated and have been reported to respond to low-dose tricyclic antidepressants and also to gabapentin and pregabalin.

Respiratory Problems

Respiratory problems, particularly sleep apnea, are often treated with significant improvement in symptoms by continuous positive airway pressure or bilevel positive airway pressure at night.

Swallowing Problems

Swallowing problems are treated conservatively, with specific recommendations from a speech and language pathologist.

Cold Intolerance

Cold intolerance is treated symptomatically, and recommendations to wear layered clothing, thermal underwear, and wool socks are given. Electrically heated stockings and insoles can also be tried.

Rehabilitation

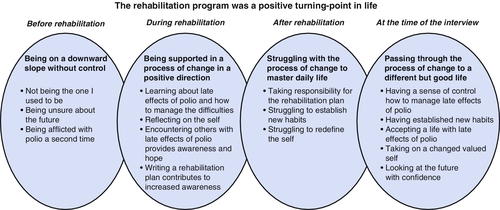

Interdisciplinary rehabilitation is the cornerstone of appropriate management in PPS [25]. Several aspects of life are often affected, so it is important that the rehabilitation team have a thorough understanding and experience of PPS. Rehabilitation in PPS can be described as a process of change. In a qualitative study, the experiences of 12 persons with PPS who had participated in an individualized, goal-oriented, comprehensive interdisciplinary rehabilitation program were presented [26]. The focus of the program was to reduce self-perceived disability by providing a variety of interventions and thereby to maximize each individual’s physical, mental, and social potential. The rehabilitation program was experienced as a turning point in the participants’ lives (Fig. 146.1). Before rehabilitation, they felt that they were on a downward slope without control. Rehabilitation was the start of a process of change whereby they acquired new skills that, over time, contributed to a different but good life. After approximately a year, they had a sense of control and had accepted life with late effects of polio. They had also established new habits, had taken on a changed valued self, and could look to the future with confidence. The participants experienced the benefits of the program developed by an ongoing and iterative process that took at least a year to complete. This emphasizes that the outcome of a PPS rehabilitation program should be assessed from a long-term perspective. The results also indicate that the effect of an interdisciplinary rehabilitation program goes beyond that of simply reducing impairments. This, in turn, emphasizes the need to select outcome measures that address the impact of rehabilitation programs in a broad sense. One newly developed rating scale that specifically assesses self-reported impairments has been presented [27]. This scale, Self-reported Impairments in Persons with late effects of Polio (SIPP), has been shown to have good psychometric properties and will facilitate the evaluation of impairments that people with PPS may experience.

Positive effects of rehabilitation were also reported in a pilot study of 27 participants with PPS. Significant improvements were noted for exercise endurance, depression, and fatigue but not for muscle strength and anxiety [28]. Another uncontrolled study found similar effects up to a year after multidisciplinary rehabilitation with emphasis on physiotherapy [29].

During a rehabilitation program, persons with PPS will be assessed by different team members and various interventions will be planned. Family members should also be encouraged to take part in the program. Many interventions cannot be evaluated until the person has actually tried them at home and later returns for follow-up. Examples of such interventions are prescription of mobility aids (scooter or power wheelchair), orthotic devices, and other adaptive equipment; teaching of compensatory techniques; medical and nonmedical interventions aimed at reducing pain, fatigue, and sleep disturbances; therapeutic home exercises, ergonomics, and vocational interventions to maintain workability; and home visits to assist in making appropriate environmental adaptation and driving adaptations [8–10]. It is therefore important that outcomes be assessed not only directly after a short rehabilitation period but also after the participants have been able to evaluate the different interventions in their preferred environment.

The exercise program should always be individualized and address flexibility, strength, and conditioning. The frequency, duration, and intensity depend very much on the distribution of PPS-related muscle weakness. For parts of the body and muscles that are not affected or only mildly affected, there are generally no restrictions. Exercise such as resistance training as well as an endurance type of training can be prescribed and may affect fatigue and quality of life positively [30]. On the other hand, whole-body vibration, a method that has gained popularity in the past decade, had no effect on muscle strength and gait performance [31]. When body parts and muscles are significantly affected by PPS, nonfatiguing protocols are preferred and the intensity of exercise must be individually tailored. EMG can often be used to decide on the type of activity, the frequency, and the duration. Non–weight-bearing exercises, such as pool exercise or cycling, are usually well tolerated, whereas high-impact exercises, such as jogging, may exacerbate pain and should be performed with caution. Appropriate prescription of orthotic devices will enable many polio survivors to walk, transfer, exercise, and function optimally within their limitations. Today, there are a variety of bracing options and materials, far from the heavy ones prescribed decades ago. Therefore, lightweight options, such as carbon fiber and Kevlar, should always be considered for this population.

Procedures

On occasion, therapeutic procedures are recommended on the basis of specific symptoms. Musculoskeletal symptoms may be treated with local steroid injections (e.g., tendinitis, osteoarthritis in the foot joints).

Surgery

Surgery should not be avoided when a disabling osteoarthritis is present. Joint replacements and carpal tunnel release can be successfully performed.

Potential Disease Complications

An important complication in PPS is falling, because of weakness and mobility problems, with subsequent injury (e.g., fracture or traumatic brain injury), and many persons with PPS complain about falls and a fear of falling [32]. Because of reduced bone mineral density, osteopenia, or osteoporosis in affected limbs, polio survivors may be more susceptible to fracture. Therefore bone mineral density studies should be considered in polio survivors with prominent weakness. Oral bisphosphonate treatment has led to significant increases in bone mineral density at the hip of PPS patients, which may have a protective effect on fracture risk [33]. Swallowing difficulties and respiratory problems can lead to pneumonia or aspiration. Also, polio survivors may be more prone to cardiovascular diseases [34], and therefore a general screening for cardiovascular risk factors in individuals diagnosed with PPS is recommended.

Potential Treatment Complications

Treatment complications may occur as a result of medication side effects and inappropriate interventions. Analgesics and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs have well-known side effects that most commonly affect the gastric, hepatic, and renal systems. Tricyclic antidepressants have cholinergic side effects, the most serious of which is the possibility of acute urinary retention in men (men with underlying prostate problems are generally at risk). Antihypertensive drugs such as beta blockers could potentially reduce muscle strength, and alternative medication for increased blood pressure should be considered. Statins can have a deleterious effect on muscle [35], which should be taken into account when they are prescribed. Polio survivors are reported to take longer to recover after general anesthesia and may require larger than the usual doses of postoperative pain medication. Careful consideration should therefore be given to the risks and benefits of surgery for this population.

During rehabilitation interventions, caution must always be used when someone’s gait and mobility are altered, such as with use of an orthotic device. Too strenuous exercises could exacerbate weakness and fatigue and increase the risk for falls.