CHAPTER 145

Polytrauma Rehabilitation

Marissa McCarthy, MD; Robert Kent, DO, MHA, MPH; Neil Kirschbaum, DO; Gail Latlief, DO; Rafael Mascarinas, MD; Bryan Merritt, MD; S. Jit Mookerjee, DO; Steven Scott, DO; Joseph Standley, DO; Jill Massengale, MS, ARNP

Definition

In 2005, the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs officially adopted the term polytrauma, originally defined as an injury to the brain in addition to other body parts. The definition changed in 2009 to be more encompassing: “two or more injuries sustained in the same incident that affect multiple body parts or organ systems and result in physical, cognitive, psychological, or psychosocial impairments and functional disabilities [1,2].”

The sequelae of polytrauma may include physical, cognitive, and psychological impairments. If a brain injury is involved, the severity typically guides the course of rehabilitation [3]. Other common disabling conditions include limb extremity trauma or amputation, spinal cord injury, neurosensory impairments, mental health disorders, and extreme soft tissue injury.

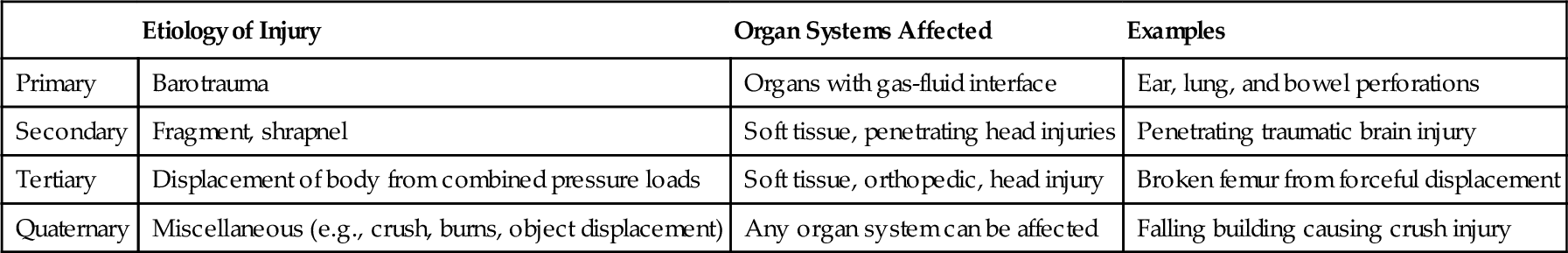

Because of the nature of modern military combat and violence in society, there is an increased risk for polytrauma injuries. Current combat-related polytrauma injuries are frequently caused by exposure to high-energy blasts or explosions [4]. Other causes of polytrauma may include severe motor vehicle accidents, falls, suicide attempts, accidental drug overdoses, and assaults. Advanced trauma life support permits increased survival among those with even the most devastating injuries (Table 145.1).

Polytrauma war-related injuries as well as civilian-based injuries occur more frequently in the younger population and predominantly in males. In noncombat conditions, active-duty men are 2.5 times more likely to have a traumatic brain injury. Military reports indicate that more than 27,000 service members serving in the current conflicts were injured between December 2001 and April 2012; of those, 49% sustained injuries classified as polytrauma. Of those injured as a result of combat operations, 62% had polytrauma injuries (K. Gross, personal communication, February 1, 2013). In the military polytrauma population, 1581 amputees have been treated in the military treatment facilities [5]. Civilian polytrauma frequency statistics are not available at this time [6,7].

Symptoms

Whereas many symptoms of polytrauma are immediately recognized, others are more subtle. Symptoms related to traumatic brain injury include cognitive, emotional, and physical impairments (see Chapter 162).

Cognitive deficits in patients with moderate to severe brain injury may include difficulties with speech and language, executive function, memory, concentration, and judgment. Irritability, anxiety, depression, and emotional lability are commonly observed. Physical symptoms of polytrauma commonly include motor and sensory deficits as well as more subtle complaints, such as headache, dizziness, fatigue, and dyssomnias. Pain is common and arises from multiple causes, complicating pain management.

Physical Examination

A thorough physical examination is essential in the evaluation of a patient who has sustained polytrauma. A mechanism of injury–directed review of systems is suggested [5]. If the mechanism of injury is blast related, the examination emphasizes testing for barotrauma to air- or fluid-filled organs. A thorough neurologic examination with complete assessment of cranial nerves (including olfactory), motor strength, sensation, reflexes, and coordination and a neuropsychological evaluation are recommended when central nervous system involvement is suspected.

A multidisciplinary approach commonly requiring specialty consultants to participate in the assessment is necessary for comprehensive care of these complex patients. Special attention is paid to the assessment of skin and soft tissue. The ideal approach is a patient-centered interdisciplinary evaluation and treatment plan coordinated by physiatry.

Functional Limitations

Polytrauma patients have multiple functional limitations based on the severity and number of physical and cognitive impairments. Hearing and visual field deficits affect everyday life functions and can make educational and vocational goals difficult to achieve. Lower extremity muscle weakness often impairs ambulation and creates a safety risk from falls. Upper extremity weakness and spasticity impair the patient’s ability to do everyday activities such as dressing, hygiene, and handwriting. Cognitive deficits affect the ability to work and to perform roles related to parenting and living independently. Particularly in the early phase of recovery, some patients may require continuous surveillance to prevent wandering or self-injurious behavior. Later in recovery, driving can be achieved in some patients after passing of a driving evaluation, which may identify necessary modifications to the current vehicle. Many polytrauma patients will experience psychosocial problems. Traumatic brain injury, stress, and mental health–related issues predispose patients to depression, anger, and mood swings. Those with brain injuries may experience significant personality changes affecting interpersonal relationships, vocational rehabilitation, and quality of life.

Diagnostic Studies

Imaging Studies

Because of the complex nature of injuries, several different imaging modalities are used to assess the central nervous system in the polytrauma patient. In general, central nervous system injury is assessed by a combination of computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging. Magnetic resonance imaging may be challenging in both military and civilian populations because of the higher incidence of retained fragments or past medical history involving a metal implant. Post-traumatic encephalomalacia, hydrocephalus, intracranial hemorrhage, diffuse axonal injury, cerebral contusions, mass effect, degree of atrophy, and spinal cord injury can be assessed by magnetic resonance or computed tomographic imaging.

Routine radiographs are often sufficient to assess axial, musculoskeletal, and visceral injuries. Other imaging techniques, such as computed tomography, bone scan, magnetic resonance, and ultrasonography, can be used when more detailed examination is necessary or for assessment of secondary complications.

Electrodiagnostics

Patients with polytrauma often sustain damage to the peripheral nervous system. A review of 33 active-duty patients admitted to the Tampa Polytrauma Rehabilitation Center revealed multiple cases of plexopathy and peripheral nerve damage due to exposure to blasts, penetrating wounds, crush injuries, and motor vehicle collisions. In this study, upper extremity nerve damage was more common than lower extremity nerve damage; multiple nerve injuries were more common than mononeuropathy [7]. Electromyography and nerve conduction studies should be considered as part of the assessment of a polytrauma patient.

Electroencephalography is a useful tool in diagnosis of post-traumatic epilepsy or encephalopathy. Seizure control and treatment of post-traumatic epilepsy are important for maximizing goal attainment during the rehabilitation process. Long-term electroencephalographic monitoring can aid in diagnosis of post-traumatic epilepsy as well as in the identification of subclinical seizures or seizure activity in patients with severe brain injuries who have not regained consciousness.

Polysomnography and actigraphy can be helpful in assessing for dyssomnias that may result after a polytrauma injury. Both sleep efficiency and sleep duration are important components of recovery, which is especially true in patients with concomitant brain injury [8].

Vascular Studies

Thromboembolic disease is a consequence of polytrauma and subsequent immobility after injury. Venous Doppler ultrasonography is frequently used to detect deep venous thrombosis in the extremities. In addition, computed tomography angiography is the diagnostic study of choice to evaluate for pulmonary embolism. Arterial Doppler ultrasonography may also be useful in the assessment of traumatic amputations to determine adequate perfusion of the residual limb.

Arterial dissection has also been documented to occur secondary to polytrauma. Traditional angiography and magnetic resonance angiography are both useful to explore the extent of dissection and superimposed thrombus after traumatic dissection.

Functional Testing

Functional testing uses sets of tests to determine performance or limitations. This testing is routinely performed by speech-language pathologists, physical therapists, and occupational therapists. Whereas overt injuries may be manifested with obvious functional deficits, milder or subclinical injuries in the presence of massive traumatic injuries may be unrecognized initially but need to be identified throughout the rehabilitation process. The intradisciplinary assessment of a polytrauma patient should include all members of the rehabilitation team to develop the full functional picture of each individual patient.

Disturbances in balance, hearing, and vision are commonly reported by polytrauma patients. Examples may include tinnitus, dizziness, and blurry vision. These disturbances result in sensory processing difficulties that affect cognitive functioning, mobility, independent performance of activities of daily living, and successful integration into the community. Evaluation and rehabilitation of the multisensory disturbances should be therapeutically integrated among specialty providers. Physical therapists with specialized training in balance disorders may perform computerized dynamic posturography to help determine the etiology of the impairment. Speech-language pathologists may be employed to evaluate dysphagia by bedside examination or video swallow study.

Neuropsychological and Psychological Evaluations

A comprehensive battery of neuropsychological and psychological tests is necessary to determine the full spectrum of cognitive and psychological sequelae from polytrauma injuries. This is typically completed once the person is medically stable, is in an acute rehabilitation program, and has emerged from a postinjury confusional state such as post-traumatic amnesia or delirium. Evaluations may be repeated to address different clinical questions during the course of recovery. Initially, assessment helps identify cognitive and emotional impairments that should be a focus of treatment. Repeated evaluations may be useful in making decisions about additional treatment needs, residential placement independence capacity, and future vocational or educational endeavors.

Differential Diagnosis

Differential diagnosis for patients sustaining polytrauma injuries is complex for seemingly simple problems. Even the cause of the injury is frequently debated. For example, brain injury can be caused by primary, secondary, and tertiary blast injuries or a combination of the three and may be traumatic or anoxic. A broad differential should be included when any problem with a polytrauma patient is considered.

The clinician must maintain a high index of suspicion for possible central nervous system infection when patients with a history of penetrating head injury present with such vague complaints as confusion, fatigue, and functional decline. Likewise, patients with a history of penetrating abdominal wounds may present with vague abdominal complaints, and an aggressive evaluation may be required for retained shrapnel and possible abscess. Musculoskeletal complaints may also be challenging, and evaluation for retained shrapnel causing impingement or nerve injury should be explored. Any complaint that does not respond to treatment as expected should be explored and the differential diagnosis widened in an effort to treat this challenging population of patients. In this regard, the potential for development of chronic pain or somatoform disorders, post-traumatic stress disorder, depression, or other psychological conditions should be considered.

Treatment

Initial

Dramatic improvement in survival is attributed to advanced trauma life support. The initial treatment is predominantly focused on maintaining medical stability and preventing further injury. With enhanced survival of catastrophic injuries, disability and impairments are increased, thus dictating the complexity of multidisciplinary rehabilitation.

Rehabilitation

Polytrauma rehabilitation is challenging in that multiple impairments must be rehabilitated concurrently. The rehabilitation process begins in the acute medical setting, such as a military treatment facility or level I trauma hospital, with the initiation of individual physical, occupational, and speech therapy. Treatment in the acute medical setting will lay the foundation for the rest of the rehabilitation process.

Successful rehabilitation of polytrauma patients requires both multidisciplinary medical care and interdisciplinary rehabilitation care. The interdisciplinary patient-centered rehabilitation team led by a physiatrist should consist of speech therapists, physical therapists, occupational therapists, nurses, blind rehabilitation specialists or certified low vision therapists, audiologists, recreational therapists, psychologists, social workers, rehabilitation counselors, family therapists, prosthetists, and others working together to minimize disability, to maximize independence, to offer psychosocial support, and to provide a rehabilitation regimen specific to each patient’s individual needs [9]. The polytrauma patients should be observed with a rehabilitation model of care from initial consultation to long-term rehabilitation care or community reintegration.

Mobility issues should be discussed with the patient or caregiver, and the most appropriate source of mobility should be considered for each individual patient. With choice of mobility, a provider must identify which type of mobility assistance provides the highest degree of independent function with the lowest degree of long-term loss of function. Some polytrauma patients are able to use manual wheelchairs, offering them a higher level of independence, whereas other polytrauma patients and their caregivers benefit from power mobility. Pressure mapping of chair cushions should also be considered in developing chairs for this population. Prosthetists and orthotists are integral members of the rehabilitation team when mobility needs of the amputee are addressed.

During the past years of conflicts in the Middle East, there has been an increase in the number and severity of urinary tract, rectal, and external genital injuries in polytrauma patients. Surgeons are faced with testicular salvage, reconstruction, and colostomies. There is an increased need for incorporating urologic care into the care of these complex injuries. The rehabilitation team faces challenges of voiding dysfunction, erectile dysfunction, infertility, and long-term psychological effects [5].

Patients with polytrauma also have increased metabolic demands. These metabolic demands are driven by factors such as healing tissue, diffuse spasticity, and rigors of the rehabilitation process. Nutrition can be further complicated by the risk of aspiration, which may require dietary changes, use of percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy or jejunostomy, and parenteral nutrition. Including a registered dietitian on the team can be extremely beneficial to these patients.

Telemedicine is an emerging technology that has proved to be an effective tool to address rehabilitation needs in this population. In the VA Polytrauma System of Care, a telehealth network was developed in 2006 to connect the interdisciplinary rehabilitation teams. This has enabled provider continuity and coordination of care from initial contact to community reintegration. Telehealth also provides enhanced options for patient access to care [10].

Multifaceted aspects of physical, psychosocial, financial, and reintegration challenges are vast. Resources for polytrauma patients are extremely individualized on the basis of the nature of the injuries. For example, patients may require special adapted housing, durable medical equipment, cognitive and physical prosthetics, vehicle modification, and mobility devices. The physiatrist has a critical role as a patient advocate. A strong working relationship with social services and caregivers is integral to the effective definition of needs and available resources. This can be a challenging but rewarding process.

Procedures

During the rehabilitation process, various interventions may be used to augment the efforts of the multidisciplinary team. Chemodenervation, intrathecal baclofen pumps, and serial casting can help reduce spasticity and improve overall mobility, hygiene, pain, caregiver burden, and function. Negative pressure wound therapy with vacuum-assisted closure may be used for large or slowly healing traumatic or postsurgical wounds, and débridement may be necessary [11]. Interventional pain procedures, trigger point and peripheral joint injections, and peripheral nerve blocks are often used to treat nociceptive pain when more conservative treatments fail. Spinal cord and peripheral nerve stimulator trials and subsequent placement are becoming more common for treatment of refractory pain [12].

Surgery

Because of the complexity of management necessary for the polytrauma patient, multiple surgical interventions may be required during the initial acute medical setting and acute rehabilitation period. Surgical examples include but are not limited to tracheostomies, percutaneous gastrostomy tubes, and external fixators. Patients may also require readmission to the hospital for subsequent surgeries, and an additional stay in the rehabilitation unit may allow the attainment of further independence goals. Patients with hydrocephalus may require placement of a ventriculoperitoneal shunt. Finally, reconstructive procedures for facial deformities, revision of skin grafts and scars, and resection of heterotopic ossification may be required in the late post-acute rehabilitation stage.

Patients who have sustained crush injuries may require fasciotomies as a result of compartment syndrome. Many patients who have sustained severe head trauma will require partial craniectomy both for removal of blood accumulation and for avoidance of further damage from cerebral edema. The removed portion of the skull is frequently unsalvageable because of fragmentation injuries. If the skull plate is salvageable, it may be either frozen or implanted into the abdominal wall for use at a later date.

The polytrauma patient frequently requires repeated surgical interventions during the acute hospitalization phase. Multiple revisions of amputated limbs as well as staged interventions for burned patients, such as repeated skin grafting, may be required.

Potential Disease Complications

Explosions have the potential to inflict multiple and severe trauma that few U.S. health care providers outside the military and the Veterans Administration have experience treating. The acute complications vary by the mechanism and pattern of trauma. Such complications can include air embolism, compartment syndrome, rhabdomyolysis, renal failure, seizures, hemorrhage, increased intracranial pressure, infections, meningitis, and encephalopathy. Early complications that follow major burns include bacterial infections, septicemia, deep venous thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, renal failure, hypovolemic shock, jaundice, glottic edema, and ileus.

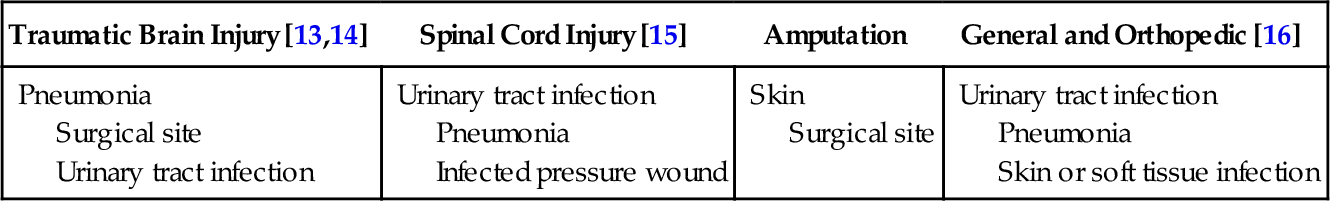

During the acute rehabilitation stage of care, there is overlap of potential complications. However, some variable patterns emerge, depending on whether the major injury is traumatic brain injury, spinal cord injury, burn, or limb amputation.

The risk of heterotopic ossification exists for traumatic brain injuries, spinal cord injuries, burns, and amputations independently; thus, concern for increased risk exists when concomitant injuries are present. Heterotopic ossification is of great concern in this population as it can decrease function, lead to increased pain, and limit rehabilitation potential (see Chapter 130).

Mental health complications are common in the polytrauma patient. Diagnoses include depression, post-traumatic stress and anxiety disorders, adjustment disorders, body image issues, and behavioral or emotional dysregulation. Any or all of these can have an impact on medication or treatment compliance and general recovery.

It is important to include an infectious disease specialist in the care of the polytrauma patient, particularly for those patients who have a recent history of exposure to endemic infections. An example of this may be an infection related to Acinetobacter baumannii in a combat-related polytrauma patient returning from Afghanistan [13] (Table 145.2).

Table 145.2

Common Infections in Polytrauma

| Traumatic Brain Injury [13,14] | Spinal Cord Injury [15] | Amputation | General and Orthopedic [16] |

| Pneumonia Surgical site Urinary tract infection |

Urinary tract infection Pneumonia Infected pressure wound |

Skin Surgical site |

Urinary tract infection Pneumonia Skin or soft tissue infection |

Cognitively impaired polytrauma patients are prone to falls because of compounding spasticity, visual impairment, impulsivity, or vestibulocochlear deficits. Along with fall issues, understanding the etiology and ramifications of the patient’s other injuries is important to map out a safe rehabilitation process. Patients’ families need to be educated on issues such as skin integrity, appropriate transfers, fall avoidance, proper wheelchair transfer and use, physical limitations, weight-bearing precautions, balance issues, and emotional stability in specific patients [17].

Potential Treatment Complications

Polypharmacy, side effects of medications, addiction to prescription pain medications, and surgical and procedural complications exist in the polytrauma patient. The use of rehabilitation equipment, orthotics, prosthetics, and other medical or adaptive devices can sometimes result in complications. Splints used in polytrauma patients to prevent joint contractures can result in pressure ulcers. Compartment syndrome, nerve injury, and infections can develop under casts that are sometimes used to treat contractures in the polytrauma population. An amputee may develop skin irritation, abrasions, ulcerations, or other skin changes from the prosthetic liner or socket.