CHAPTER 144

Plexopathy—Lumbosacral

Hope S. Hacker, MD; John C. King, MD; John D. Alfonso, MD

Definition

Lumbosacral plexopathy is an injury to or involvement of one or more nerves that combine to form or branch from the lumbosacral plexus. This involvement is distal to the root level.

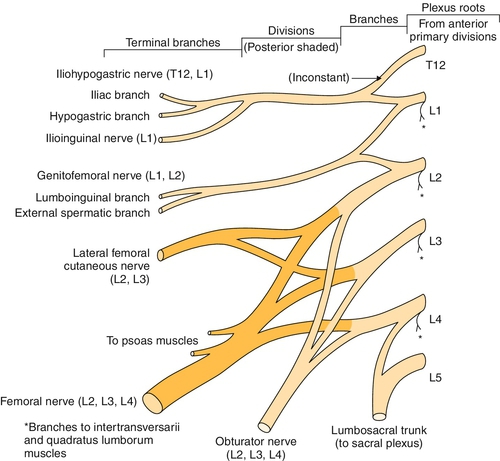

The lumbar plexus originates from the first, second, third, and fourth lumbar nerves (Fig. 144.1). The fourth lumbar nerve makes a contribution to both the lumbar and the sacral plexus. There is typically a small communication from the twelfth thoracic nerve as well. As in the brachial plexus, these nerve roots divide into the dorsal rami and the ventral rami as they exit through the intervertebral foramina. The dorsal or posterior rami innervate the paraspinal muscles and supply nearby cutaneous sensation. The ventral or anterior rami of the lumbar plexus form the motor and sensory nerves to the anterior and medial sides of the thigh and the sensation on the medial aspect of the leg and foot. The undivided anterior primary rami of the lumbar and sacral nerves also carry postganglionic sympathetic fibers that are mainly responsible for vasoregulation of the lower extremities. The branches of the lumbar plexus include the iliohypogastric, ilioinguinal, genitofemoral, femoral, lateral femoral cutaneous, and obturator nerves [1]. The lumbar portion of the plexus lies just anterior to the psoas muscle [2].

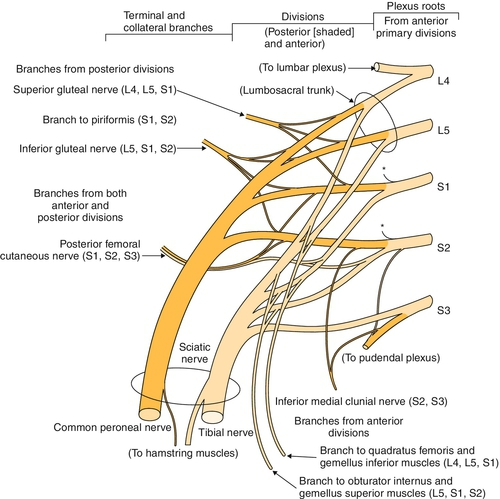

The sacral plexus innervates the muscles of the buttocks, posterior thigh, and leg below the knee and the skin of the posterior thigh and leg, lateral leg, foot, and perineum. It is formed from the lumbosacral trunk to include L5 and a portion of L4 as well as the S1 to S3 (or S4) nerve roots (Fig. 144.2). The anterior primary rami of S2 and S3 nerve roots carry parasympathetic fibers that mainly control the urinary bladder and anal sphincters. The triangular sacral plexus lies on the anterior surface of the sacrum, in the immediate vicinity of the sacroiliac joint and lateral to the cervix or prostate [1]. The branches of the sacral plexus include the superior and inferior gluteal nerves, the posterior cutaneous nerves of the thigh, the lumbosacral trunk that becomes the sciatic nerve with both tibial and peroneal divisions, and the pudendal nerve.

Etiology

Lumbosacral plexopathy has been recognized as a clinical entity or complication in a variety of surgical procedures, trauma, and obstetric surgery or delivery and as a clinical finding or sequela in treatment of pelvic tumors.

Trauma

Traumatic pelvic fractures have a 30.8% incidence of lumbosacral plexus injury [3,4]. The incidence and severity of traumatic lumbosacral plexopathy increase with the number of pelvic fracture sites and fracture instability [4]. Sacral fractures have typically been considered of secondary importance in conjunction with pelvic trauma [5]. However, sacral fractures have become recognized as an essential consideration in pelvic trauma because of their high association with lumbosacral nerve deficits. This can have a profound influence on prognosis and level of functional recovery [3,6]. The more common sacral fractures are typically the compression or avulsion fractures of the sacral ala, which can occur in lateral compression and anterior-posterior compression pelvic fractures [7]. Fractures of the sacral neuroforamina or midline sacral fractures may also occur. Fractures of the sacrum can increase the incidence of neurologic injury in pelvic trauma to between 34% and 50% because of its proximity to the sacral nerve roots [7].

Gunshot wounds and motor vehicle accidents have long been recognized as potential causes of lumbosacral plexus injuries. In a retrospective comparison of patterns of lumbosacral plexus injury in motor vehicle crashes and gunshot wounds, individuals with gunshot wounds had a greater chance of involvement of the upper portion of the plexus in comparison to individuals who sustained a motor vehicle crash. Lower plexus injuries were more common in victims of motor vehicle accidents as opposed to gunshot wounds [8].

Finally, trauma is a common cause of retroperitoneal hemorrhage, which can injure the lumbosacral plexus.

Labor and Delivery

The lumbosacral plexus may be compressed as a complication of labor and delivery. The incidence of neurologic injury that is reported in the literature for postpartum sensory and motor dysfunction is relatively low at 0.008% to 0.5% [9,10]. Factors associated with nerve injury were nulliparity and a prolonged second stage of labor; assisted vacuum or forceps vaginal delivery also had some positive association. Women with nerve injury spent more time pushing in the semi-Fowler lithotomy position. During the second stage of labor, direct pressure of the fetal head may compress the lumbosacral plexus against the pelvic rim, which may result in nerve injury [11,12].

Iatrogenic

Gynecologic surgery is thought to be one of the most common causes of femoral nerve injury (see Chapter 54) and lumbosacral plexus nerve injuries. Abdominal hysterectomy is the surgical procedure that has been most frequently implicated [13,14]. The mechanisms of neurologic injury that have been established include improper placement or positioning of self-retaining or fixed retractors, incorrect positioning of the patient in lithotomy position preoperatively or prolonged lithotomy positioning without repositioning, and radical surgical dissection resulting in autonomic nerve disruption [15].

Lumbosacral injury has also been noted after appendectomy and inguinal herniorrhaphy. Patients who are thin, diabetic, or elderly are at increased risk for such an injury. Injury to the lumbosacral plexus with clinical findings occurs in up to 10% of hip replacement procedures, and injury that is subclinical but detected electromyographically occurred in up to 70% of patients [16].

In individuals receiving anticoagulant therapy or with acquired or congenital coagulopathies, retroperitoneal hemorrhage causing lumbosacral plexopathy may occur with no precipitating injury [17,18].

Retroperitoneal hematoma has also been documented as a rare but potentially serious complication after cardiac catheterization [19,20]. In a review of 9585 femoral artery catheterizations, a reported retroperitoneal hematoma rate of 0.5% occurred. In patients undergoing stent placement, there was evidence of lumbar plexopathy involving the femoral, obturator, and lateral femoral cutaneous nerves, and the condition was typically completely reversible [21,22]. Femoral vein catheterization for dialysis has also been documented as a cause of hemorrhagic complications and retroperitoneal hemorrhage [23].

Case reports have also identified patients sustaining lumbosacral plexopathy after undergoing aortoiliac bypass grafting for abdominal aortic aneurysm. The proposed mechanism for this rare complication, with fewer than 80 patients reported in the literature, is neural ischemia secondary to interruption of the blood supply to the lumbosacral plexus or caudal portion of the spinal cord [24,25].

Oncologic

Both pelvic malignant neoplasms and treatment of pelvic tumors can damage the lumbosacral plexus. Lumbosacral radiculopathy is most common with gynecologic tumors, sarcomas, and lymphomas. Neoplastic plexopathy is characterized by severe and unrelenting pain, typically followed by weakness and sensory disturbances [26]. Pelvic radiation therapy may cause a delayed lumbosacral plexopathy that can occur 3 months to 22 years after completion of treatment; the median amount of time from the completion of treatment to onset of symptoms is about 5 years [27–29]. Chemotherapeutic agents can also cause symptoms of lumbosacral radiculopathy. Cisplatin, 5-fluorouracil, mitomycin C, and bleomycin have been implicated in the majority of these plexopathies [2]. Metastatic or tumor extension into the lumbosacral plexus and malignant psoas syndrome have been described in the literature. Malignant psoas syndrome was first reported in 1990. It is characterized by proximal lumbosacral plexopathy, painful fixed flexion of the ipsilateral hip, and radiologic or pathologic evidence of ipsilateral psoas major muscle malignant involvement [2].

Diabetic Amyotrophy

Diabetic and nondiabetic lumbosacral radiculoplexus neuropathies have been documented in the literature. Diabetic lumbosacral radiculoplexus neuropathy is a subacute, painful asymmetric lower limb neuropathy that is associated with significant weight loss (at least 10 pounds), type 2 diabetes mellitus, and relatively recent diagnosis of diabetes with relatively good glucose control [30]. The underlying pathophysiologic mechanism is thought to be immune mediated with microvasculitis of the nerve rather than a metabolic issue caused by diabetes; nondiabetic lumbosacral radiculoplexus neuropathy has also been documented with similar clinical and pathophysiologic features [30–34]. The similar clinical symptoms, findings, and response to treatment suggest that the metabolic changes from diabetes may not be the cause of these symptoms, although impaired glucose tolerance has been noted in nondiabetic lumbosacral radiculoplexus neuropathy [32].

Vascular

Vascular causes of lumbosacral plexopathies may include diabetic amyotrophy and connective tissue diseases that may be associated with vasculitis, such as systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, and polyarteritis nodosa [35]. Further, a recently published case report described acute lumbosacral plexus injury secondary to direct compression by an internal iliac artery aneurysm [36]. If a vascular cause is suspected, the aorta and iliac vessels must be evaluated for disease or occlusion [37–39].

Symptoms

Plexopathies may vary considerably in their presentation, depending on the location and degree of involvement. Lumbosacral plexopathy often begins with leg pain radiating to the low back and buttocks and progressing posterolaterally down the leg, soon followed by symptoms of numbness and weakness. Lumbosacral plexus injuries are often associated with a footdrop and sensory changes to the top of the foot. A plexopathy involving the upper lumbar roots may primarily be manifested by femoral and obturator nerve symptoms. Femoral nerve injury typically is manifested with iliopsoas or quadriceps weakness, and there may be sensory deficits over the anterior and medial thigh as well as the anterior medial aspect of the leg [13]. Obturator injury has also been seen in upper plexus injuries with weakness of the hip adductors [10] and sensory changes in the upper medial thigh.

Diabetic plexopathy typically starts as an identifiable onset of asymmetric lower extremity symptoms that most typically involve the thigh and hip with pain that progresses to include weakness, which then becomes the main disabling symptom. In a few months, this usually evolves into bilateral symmetric weakness and pain with distal as well as proximal involvement. Although motor findings are prominent, sensory and autonomic nerves have also been shown to be involved [29].

Bowel and bladder injuries tend to occur in cases in which there is bilateral sacral root involvement. Sexual dysfunction has been documented in both bilateral and unilateral sacral injuries and pelvic trauma. Lumbosacral plexus injuries are much more common in pelvic and sacral fractures but have been documented in acetabular fractures and midshaft femoral fractures as well [3,6,26].

Physical Examination

Clinical examination to evaluate for a lumbosacral plexopathy involves neurologic assessment to include motor strength testing, sensory testing, muscle stretch reflexes, tone, and bowel and bladder function. The pattern of sensory loss, asymmetric reflexes, or weakness is suggestive of multiple nerve or root level involvement. It is important to differentiate a suspected plexus injury from single root level involvement, suggesting a radiculopathy, or more generalized nerve changes consistent with peripheral neuropathy. A detailed examination of the bilateral lower limbs, including skin sensory testing of all dermatomes, manual muscle testing of all myotomes, and examination of the patellar and Achilles deep tendon reflexes, can reveal neurologic deficits that can aid in this differentiation. In addition, it may be necessary to evaluate lower sacral involvement by physical examination of a patient’s external anal sphincter tone, particularly if complaints include bowel and bladder incontinence. Edema or swelling in one lower extremity may be suggestive of a pelvic mass or lumbosacral plexus involvement rather than a more global peripheral neuropathy [38] or possible retroperitoneal hematoma or pelvic malignant neoplasm [2].

Functional Limitations

Functional limitations depend on which portions of the lumbar or lumbosacral plexus have been injured and the severity of the injury. Patients frequently present with some type of difficulty with mobility and ambulation. Activities such as transferring from one surface to another, rising from a chair, ambulation, grooming, bathing, dressing, and cooking may potentially be affected. These functional limitations may have far-reaching consequences on one’s ability to live independently and to continue in one’s chosen vocation.

Diagnostic Studies

Electrodiagnostic Testing

The electrodiagnostic evaluation of lumbosacral plexopathy is one of the most effective tools available for differentiation of a specific pattern and severity of nerve involvement. Guided by a focused history and physical examination, the skilled electromyographer can use testing of both proximal and distal sensory and motor nerves as well as muscle needle examination to determine whether there is radicular involvement, lumbar or lumbosacral plexus involvement with multiple nerves involved but no paraspinal involvement, or a more generalized picture consistent with a peripheral neuropathy.

Testing for upper lumbar plexopathy may include lateral femoral cutaneous nerve, saphenous nerve, posterior femoral cutaneous sensory nerve, and femoral motor nerve studies. Side-to-side comparison is recommended to assess for asymmetry in these technically challenging studies. Sensory involvement without motor involvement suggests a lesion distal to the dorsal root ganglion. Studies to evaluate the lumbosacral plexus and lumbosacral roots include sural and superficial peroneal sensory studies, H reflex, and peroneal and tibial motor conduction studies. Depending on the timing of the injury, nerve conduction studies can demonstrate a decrease in amplitude for the sensory nerve action potentials starting at 5 to 6 days and for compound muscle action potentials starting at 2 to 4 days [8].

The needle electromyographic examination is likely to be the most useful electrodiagnostic technique [8]. Careful examination of proximal and distal musculature demonstrates a pattern of muscle membrane instability in more than one peripheral nerve from different root levels without involvement of the paraspinal muscles. The pattern of muscle membrane instability indicates whether the injury appears to be a neurapraxia with conduction block, axonotmesis, or neurotmesis with wallerian degeneration and poor prognosis for reinnervation. Increased insertional activity may be seen in the involved musculature after 7 to 8 days, with positive waves and fibrillations starting at 10 to 30 days but being most prominent at 21 to 30 days after injury [8]. Decreased recruitment is noted immediately after injury, and this may be the only change on needle electromyographic examination in the first few days if the nerve is partially intact.

Imaging Studies

Computed tomography and positron emission tomography can be useful in determining the presence of a structural mass in the pelvic region. Computed tomographic scans, along with abdominal ultrasonography, may be used to diagnose a retroperitoneal hemorrhage. Both computed tomographic scanning and magnetic resonance imaging have been used to evaluate the lumbosacral plexus. Magnetic resonance imaging has been found to be more sensitive than computed tomography for diagnosis of cancer-related lumbosacral plexopathy [40]. High-resolution magnetic resonance neurography with T1-weighted fast spin echo and fat-saturated T2-weighted fast spin echo has been used to study the lumbosacral plexus and the sciatic nerve [41]. Plain radiographs are useful as a screening tool for suspected aneurysms or malignant disease.

Treatment

Initial

Initial treatment is based on both the presenting symptoms and the cause of the lumbosacral plexopathy. For example, many obstetric lumbosacral plexus symptoms are treated conservatively. Pelvic masses or a retroperitoneal hemorrhage may require surgical or medical intervention. Neoplastic or radiation-based plexopathy symptoms may need specific medical management, chemotherapy, or possibly surgery. If edema control is necessary, leg elevation and compressive stockings may be of some benefit. Medication for neuropathic pain might include gabapentin, duloxetine, or pregabalin. Tricyclic antidepressants may also be helpful. Opioids and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs may also provide pain relief. Use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs is contraindicated, however, when hemorrhage is suspected. Various immunomodulation therapies for diabetic amyotrophy, including corticosteroids, cyclophosphamide, intravenous immune globulin, and plasmapheresis, have been described in a number of case series, most of which report positive outcomes with regard to resolution of pain and weakness [29,34]. To date, only one multicenter, double-blind controlled study of intravenous methylprednisolone in diabetic amyotrophy exists, but it is as yet unpublished [42]. Therefore, at this time, the literature still lacks strong evidence from randomized controlled trials to definitively recommend the use of immunotherapy for diabetic lumbosacral radiculoplexus neuropathies.

Rehabilitation

Rehabilitation aims to maximize mobility and functional independence. The goals of rehabilitation are preservation of joint range of motion and flexibility, joint protection, and pain management; these goals depend on a good physical examination to determine what neurologic and functional deficits are present.

One of the primary rehabilitation concerns in an individual with nerve involvement in the lumbar or lumbosacral plexus is safe mobility and ambulation. The patient should be evaluated for the need for an assistive device, such as a cane or a walker, with ambulation. Patients with significant footdrop impairing gait benefit from prescription of ankle-foot orthoses, with dorsiflexion assist as an option. Energy conservation techniques and care of insensate feet are key treatment tools. Symptoms of lumbosacral plexopathy may be subtle and may be difficult to appreciate in a clinical setting. Physicians need to address potentially sensitive issues such as work limitations, sexual functioning, and sensory changes in the pelvic and inguinal areas.

Procedures

Sympathetic nerve blocks and chemodenervation have both been used to ameliorate pain. This can be both diagnostic and treatment oriented in helping to confirm the suspected diagnosis. Sacral nerve stimulation has been evaluated for adjunctive treatment of lumbosacral plexopathy, but further research is required for its effectiveness to be determined [17].

Surgery

Lumbosacral plexus injuries associated with pelvic or sacral fractures or with gynecologic surgery are often treated conservatively [13], although it has been documented that long-term sequelae can occur. Nerve reconstruction including nerve grafting has been reported in an attempt to restore some lower extremity function [43]. Microsurgical treatment of lumbosacral plexopathies for neurolysis and nerve grafting has been used in the retroperitoneal space. In a series of 15 cases, the muscles that benefited the most from surgery were the gluteal and femoral innervated muscles. The more distal musculature did not seem to show much benefit [44]. Whereas motor improvement is an important consideration, pain is often extremely debilitating in patients with a lumbosacral plexopathy and may block or limit rehabilitation. Pain relief is one of the major goals for surgical intervention. Surgical resection of a tumor may also be indicated in certain cases with lumbosacral plexopathy [26].

Potential Disease Complications

Potential complications of lumbosacral plexopathy include joint contractures, limited mobility, weakness, falls secondary to weakness or sensory loss, bowel or bladder incontinence, diminished or absent sensation, skin breakdown, sexual dysfunction, and significant decrease in functional independence from these complications. The rare complication of complex regional pain syndrome type II has also been reported [45].

Potential Treatment Complications

Treatment complications may include skin breakdown under orthoses and increased weakness if the rehabilitation program is too aggressive. Medication side effects are dizziness, somnolence, gastrointestinal irritation, and ataxia due to anticonvulsants; dry mouth, urinary retention, and atrioventricular conduction block due to tricyclic antidepressants; and dependence, dizziness, somnolence, and constipation due to opioid pain medications. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and analgesics can also have significant side effects that affect the gastrointestinal and renal systems as well as the liver.