CHAPTER 142

Peripheral Neuropathies

Definition

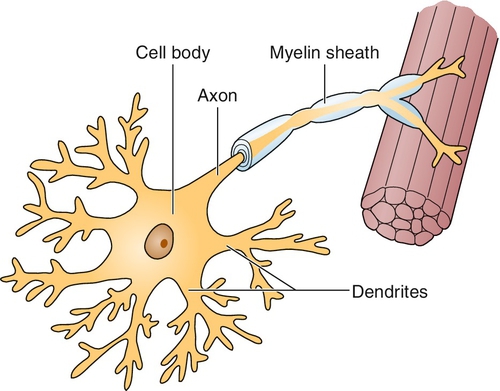

Peripheral neuropathies are a collection of disorders characterized by the generalized dysfunction of peripheral nerves. This group of diseases is heterogeneous, including those that predominantly affect the nerve axon, others that primarily affect the myelin sheath, and still others that involve both parts of the nerve simultaneously. In addition, some peripheral neuropathies affect only small, unmyelinated fibers, whereas others predominantly involve only large myelinated ones. Table 142.1 contains a list of the most frequently encountered forms of peripheral neuropathy.

Peripheral neuropathy is common; one Italian study suggested a prevalence of about 3.5% in the general population [1]. In diabetes, one study demonstrated clinical peripheral neuropathy affecting 8.3% of individuals compared with a control population, in whom 2.1% of individuals were affected [2]. After 10 years, 41.9% of the diabetic patients had peripheral neuropathy compared with 6% of the control subjects.

Defining peripheral neuropathy remains no simple task. Members of the American Academy of Neurology along with those of the American Association of Electrodiagnostic Medicine and the American Academy of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation have developed a formal case definition for distal symmetric polyneuropathy (the most common form) [3]. The authors chose to use a combination of symptoms, signs, and electrodiagnostic testing results to formulate an ordinal ranking system to identify the likelihood of the disease in a given patient. Although it is a useful tool for future research studies, the necessity of applying such a complex approach underscores the difficulty in attempting to define peripheral neuropathy in any simple fashion.

Symptoms

Patients with peripheral neuropathy present with a number of specific sensory complaints, including decreased sensation often associated with pain, tingling (paresthesias), and burning. They may complain of a “sock-like” feeling in the feet or that the feet are persistently cold. Some patients, usually with more advanced disease, will note atrophy of the intrinsic foot muscles and some weakness, especially with the development of partial footdrop. Walking difficulties usually also develop once sensation is significantly impaired. Sensory symptoms in the hand (paresthesias and reduced tactile sensation) usually develop once an axonal peripheral neuropathy has progressed up to about the level of the knees. In patients with generalized demyelinating peripheral neuropathies, more generalized symptoms of weakness and sensory loss are often present, although distally predominant paresthesias often occur. The history includes a detailed past medical history, review of systems, and any prior exposure to toxins (Table 142.2).

Physical Examination

The physical examination demonstrates distinct abnormalities that depend on the form of peripheral neuropathy present. Most commonly, patients present with a sensorimotor axonal peripheral neuropathy. In this condition, decreased sensation to pinprick, vibration, light touch, and temperature may be identified distally in the lower extremities with normal sensation more proximally. Of note, vibration sensation testing with a tuning fork has been shown to be reliable [4]. Some weakness of toe or foot extension and flexion may also be apparent. Deep tendon reflexes will be hypoactive distally (e.g., ankle jerks decreased relative to knee jerks).

In patients with acquired demyelinating peripheral neuropathy, the examination may demonstrate marked generalized weakness with some abnormal sensory findings, usually including decreased joint position sense. In this disorder, deep tendon reflexes may be reduced or diffusely absent. Patients with hereditary demyelinating polyneuropathies may demonstrate distal muscle atrophy in the feet and lower legs. Such patients may develop a pes cavus foot deformity, in which the foot is foreshortened and has a very high arch. A “champagne bottle” appearance to the legs (where muscle atrophy of the lower leg, especially of the calf, is prominent) may also be present. As any peripheral neuropathy progresses, lower extremity sensory loss may lead to gait unsteadiness, and upper extremity sensory loss may produce decreased hand dexterity.

Functional Limitations

Patients with peripheral neuropathy face a number of potential functional limitations. In those individuals with a distal axonal peripheral neuropathy, limitations usually include problems with gait and unsteadiness, especially as the neuropathy progresses. If pain is a prominent symptom, the activities of daily living may be compromised to some extent. Pain may also be prominent at night, interfering with sleep. In those patients with very advanced axonal peripheral neuropathy or demyelinating forms, such as hereditary Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease, weakness can produce major functional limitations, restricting the patient’s walking ability and in some cases leading to dyspnea and nocturnal hypoventilation. In patients with some chronic forms of demyelinating polyneuropathy, weakness of both proximal and distal muscles can become severe, limiting the performance of many activities of daily living. Sensory deficits can limit one’s ability to button shirts, to zip pants, to turn a key in a lock, to tie shoelaces, or to type on a computer.

Diagnostic Studies

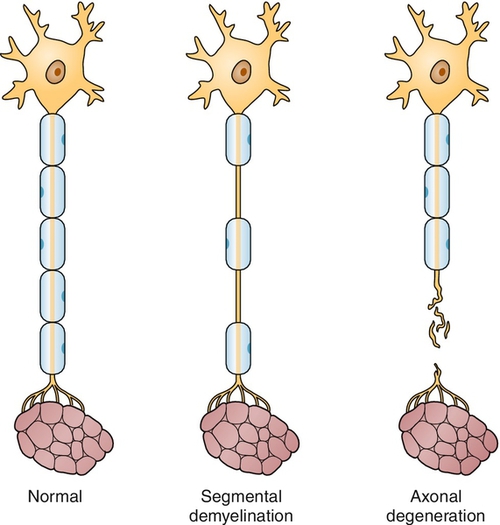

Electrodiagnostic studies (including electromyography and nerve conduction studies) remain the most important first tests in the evaluation of polyneuropathy [5]. Nerve conduction studies assist in determination of whether the peripheral neuropathy is mainly demyelinating, axonal, or mixed (Figs. 142.1 and 142.2) by evaluation of the amplitude and conduction velocities of the motor and sensory responses obtained [6]. In axonal neuropathies, amplitudes are reduced and conduction velocities are relatively normal; in demyelinating neuropathies, amplitudes are generally preserved but conduction velocities are decreased; in mixed neuropathies, a combination of reduced amplitude and conduction velocities is present. In small-fiber neuropathies, nerve conduction studies are generally normal. Likewise, nerve conduction studies help determine the severity of the process as well. Although needle electromyography plays a more limited role in the diagnosis of peripheral neuropathy, a gradient of reinnervation, in which distal muscles are most abnormal and proximal muscles less affected, helps determine the degree of motor involvement. In addition, needle electromyography may assist in determining whether a superimposed problem, such as polyradiculopathy, is also contributing.

In general, a number of serologic tests are also performed to identify the cause of the peripheral neuropathy. These are outlined in Table 142.3.

Additional workup is occasionally necessary. Sural nerve biopsy can be useful for determining the cause of the polyneuropathy for some conditions that are difficult to diagnose, such as amyloid neuropathy, as well as some other unusual forms of peripheral neuropathy. The analysis of cutaneous sensory fibers through the use of skin biopsy to identify the presence of peripheral neuropathy involving only small, unmyelinated fibers is now also routinely performed to assist with the diagnosis of idiopathic small-fiber neuropathy or that associated with certain conditions, such as amyloid [7]. On occasion, muscle biopsy may be helpful in this regard as well because vasculitic abnormalities or amyloid can also be identified in skeletal muscle. Lumbar puncture may aid in the determination of whether an acquired demyelinating peripheral neuropathy is present by the identification of a very elevated cerebrospinal fluid protein concentration in the presence of a normal number of white cells (so-called albuminocytologic dissociation). Autonomic testing, such as quantitative sudomotor axon reflex texting, tilt-table testing, and heart rate variability to deep breathing, can also be helpful in delineating the involvement of the autonomic nervous system in the neuropathic process [8].

Treatment

Initial

If a cause of the axonal peripheral neuropathy is known or identified (which generally is achieved about 80% of the time), treatment geared toward the underlying disorder itself might help slow progression of the polyneuropathy. For example, improved glucose control can help improve neuronal function in diabetic neuropathy [9]. Likewise, in those people with a neuropathy secondary to toxin exposure, such as alcoholic neuropathy, decreased exposure to the toxin may be helpful.

In patients with axonal peripheral neuropathies, treatment is usually symptom based, with efforts toward reducing pain and dysesthesias. A number of drugs have proved useful in this regard [10]. The tricyclic antidepressants remain most effective (generally nortriptyline or amitriptyline, starting with 10 mg at bedtime and increasing as needed until improvement occurs). Gabapentin (starting at a dose of 100 to 300 mg three times daily) has also gained wide acceptance in the treatment of this disorder during the past several years [11]. Two newer drugs specifically approved for use in diabetic polyneuropathy, duloxetine (Cymbalta), at 30 mg or 60 mg daily, and pregabalin (Lyrica) at a dose of 50 mg three times daily, increasing to 100 mg three times daily if needed, can be useful in a variety of peripheral neuropathies [12,13]. However, it is not clear that either of these is more efficacious than previously available and more inexpensive medications [14]. In patients in whom these measures prove of limited value, the use of long-acting narcotic agents may occasionally be necessary. In patients with certain forms of demyelinating peripheral neuropathy (such as chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy), immunosuppressive or immunomodulating therapies can make a dramatic difference in the patient’s symptoms and level of function. Drugs including corticosteroids, azathioprine, cyclosporine, and cyclophosphamide can be used [15]. Intravenous immune globulin and plasmapheresis are also widely used in this group of disorders [16,17]. Finally, in all patients with distal sensory loss due to peripheral neuropathy, and especially in those with diabetic peripheral neuropathy, regular podiatric care is extremely important in preventing the development of serious foot complications, such as ulcerations [18].

Rehabilitation

Physical therapy may be recommended to improve mobility, muscle strength, and balance. In patients with moderate to severe peripheral neuropathy, gait training may consist of balance exercise and use of an assistive device, such as a cane or walker. Either a physical or occupational therapist can review falls precautions (e.g., avoiding throw rugs in the home, using a chair in the bath or shower). Some patients may benefit from an ankle-foot orthosis. However, in patients with compromised sensation, monitoring of the skin to prevent breakdown when a brace is used is critical. Patients can be taught to self-monitor their skin with use of a long-handled mirror to check the bottom of their feet. Custom shoes (e.g., extra depth and width) may be beneficial, as can custom shoe orthoses.

In patients with more advanced peripheral neuropathy, evaluation by an occupational therapist may help maximize the function of the hands and arms. The occupational therapist can provide the patient with information about adaptive equipment, such as elastic shoelaces, wide grip handles for cookware and utensils, and shoehorns. An occupational or physical therapist experienced in assistive technology can also be helpful in specialized equipment, such as voice-activated computer software, driving adaptations, and environmental control units.

If pain is an issue, therapeutic modalities may be used to alleviate the pain. These may include instruction on use of transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation, paraffin baths, and the like. It is important to caution the patient with impaired sensation not to use any heat or ice that may cause burns or frostbite. Individuals with impaired vascular status also should be advised not to use ice because of its vasoconstrictive effects.

Procedures

Patients with peripheral neuropathy are generally at increased risk for development of superimposed compressive neuropathies, such as carpal tunnel syndrome, that can be challenging to diagnose [19]. Treatment with local corticosteroid injections can be helpful for this problem (see Chapter 36).

Surgery

Surgery may be necessary for some associated conditions, including severe carpal tunnel syndrome, but it is usually more relevant to patients who develop infections of the distal lower extremities and require amputations. Other, less severe distal leg problems may also develop, requiring orthopedic or podiatric surgery. Although lower extremity nerve release surgeries are sometimes performed in the hope of treating neuropathic symptoms [20], there is little evidence to support the use of these procedures to treat peripheral neuropathy [21].

Potential Disease Complications

A number of potential foot complications can occur, including persistent, intractable pain, skin ulcerations, and foot trauma, possibly leading to amputations. Serious trauma secondary to increased gait unsteadiness is another potential problem. Finally, depression due to immobility and persistent pain also often plays a role in patients with more advanced peripheral neuropathy.

Potential Treatment Complications

The tricyclic antidepressants and other pain medications have the potential side effect of drowsiness. Dry mouth, constipation, and urinary retention also occur commonly with the tricyclic antidepressants. Side effects of duloxetine include dizziness, nausea, and constipation. Side effects of pregabalin include dizziness and somnolence. Addiction remains a major concern with narcotic use.

Treatment of the autoimmune peripheral neuropathies poses significant risk, given the inherent toxicity of the medications employed. Patients using immunosuppressive medications are at increased risk for infection, malignant neoplasia, anemia, and multiple other side effects (e.g., liver toxicity with azathioprine, renal failure with intravenous immune globulin, hemorrhagic cystitis with cyclophosphamide).

Skin breakdown can occur with improper bracing.