CHAPTER 141

Parkinson Disease

Definition

Parkinson disease (PD) is a chronic, progressive neurodegenerative disease. On pathologic examination, it is characterized by preferential degeneration of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra pars compacta and the presence of cytoplasmic inclusions known as Lewy bodies. It is characterized clinically by a resting tremor, bradykinesia, and rigidity. It is important to distinguish PD from the disorders that are known collectively as the Parkinson-plus syndromes. These are relatively rare disorders that share some of the features of PD, such as rigidity and bradykinesia. However, the Parkinson-plus syndromes do not respond to medical treatment and have some unique clinical features as well.

The prevalence of PD has been estimated in more than 80 studies conducted around the world. The most consistent finding is that PD is an age-related disease. Between the ages of 50 and 59 years, the prevalence is estimated at 273 per 100,000, whereas between 70 and 79 years, the prevalence is estimated at 2700 per 100,000 [1]. Some studies have reported a higher prevalence of PD in men, whereas other studies have not.

The genetic contribution to the development of PD is an area of intense study. A variety of gene mutations that can cause PD have been identified in family studies [1]. However, their contribution to the development of PD in a larger population is not yet fully appreciated. Environmental risk factors are also thought to play a role in the pathogenesis of PD. Numerous studies have focused on the risk of pesticide and heavy metal exposure to the development of PD. Whereas the methodology varies in different studies, in those with an occupational exposure to pesticides or heavy metals, the data have been mixed, indicating either an increased risk for development of PD or no increased risk [1].

Symptoms

The most common initial manifestations of PD are rest tremor and bradykinesia. The resting tremor is suppressed by either purposeful movement or sleep and exacerbated by anxiety. The bradykinesia may produce a sensation of stiffness in the affected arm or leg. Pain is also a part of PD. An aching pain in the initially affected limb may first be attributed to bursitis or arthritis. Less common presenting complaints include gait difficulty and fatigue. It is not uncommon for one of these features to be present for months or even years before others develop.

As the disease progresses, there is marked difficulty in both initiating and terminating movement. There is difficulty in rising from a seated position, particularly when one is seated in a sofa or chair without armrests. Handwriting becomes smaller and more difficult to read. Friends and family members often complain that the patient’s speech is more difficult to understand, particularly on the telephone. The symptom of a softer voice with a decline in enunciation is known as hypophonia.

Physical Examination

The most distinctive clinical feature is the rest tremor. It is typically present in a single upper extremity early in the course of the disease. As the disease progresses, the resting tremor may spread to both the ipsilateral lower limb and the contralateral limbs. Examination of motor tone reveals cogwheel rigidity in the affected limb. Motor strength, however, remains unaffected.

Additional features that must be evaluated in an examination include rapid, repetitive limb movements and gait. Examination of repetitive movements of the fingers or entire hand will reveal bradykinesia and decreased amplitude and accuracy of finger tapping or toe tapping movements in the affected limb. Examination of gait will reveal decreased arm swing on the affected side, smaller steps, and an inability to pivot turn. Typically, patients make several steps to complete a turn because of some degree of postural instability. Deep tendon reflexes and sensation are not affected in PD.

In advanced PD, loss of postural reflexes becomes evident. Individuals are unable to maintain balance when turning. Other manifestations of advanced PD include freezing episodes and dysphagia. There is also a spectrum of cognitive impairment in PD, extending from minimal cognitive impairment to PD with dementia. Minimal cognitive impairment is defined as a gradual decline in cognitive function, identified by the patient or caregiver, that does not interfere significantly with functional independence [2]. PD with dementia is dementia with a slowly progressive course of cognitive impairment that most prominently affects attention, executive, and visuospatial functions [3].

In examination of someone who is taking medication for PD, it is important to record the time at which the last dose of medication was taken relative to the time at which the examination occurs. Medications for PD are particularly good at ameliorating the rest tremor and bradykinesia, particularly in the early stages of the disease. Typically, the rest tremor will subside for 1 to 3 hours after the last dose of medication. Other features, such as reduced arm swing, hypophonia, and loss of postural reflexes, do not respond to oral medication.

Functional Limitations

Functional limitations depend on which symptoms are most prominent in a particular patient. Early in the course of PD, the sole limitation may be in one’s ability to write legibly. Affected individuals are still able to perform activities of daily living, although they may prefer to use the unaffected limb for tasks such as shaving and dressing. Although the rest tremor may result in a feeling of self-consciousness or embarrassment, it does not affect one’s independence as it is suppressed with purposeful movement.

As the disease progresses, the ability to perform fine motor skills declines, and difficulty with standing and gait develops. An individual will have difficulty in buttoning a shirt or tying shoelaces. More time will be required to stand and to initiate gait. Postural instability with a tendency to retropulse also develops. Thus patients have difficulty in climbing stairs and walking safely and quickly. Slowed reaction times may also affect one’s ability to drive safely. Decisions about whether someone should drive are often difficult and must be made on an individual basis. Marked hypophonia may make speaking on the telephone difficult as well. As the voice becomes more affected, dysphagia is likely to develop.

One aspect of PD that has historically received little attention is the effect it has on sexual activity. Men may experience erectile dysfunction and difficulty with ejaculation as part of the autonomic dysfunction found in PD. Women may experience inadequate lubrication and a tendency to urinate during sex secondary to autonomic dysfunction. In both genders, hypersexuality may be seen as a side effect of treatment with dopamine agonists [4].

In end-stage PD, limitations include marked dysphagia and severe abnormalities of gait that require both devices and one or two persons for assistance. At this stage, help is necessary for all activities of daily living as well.

Diagnostic Studies

PD is a clinical diagnosis. Conventional laboratory investigations do not contribute to the diagnosis or management of PD. Computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging scans of the brain do not reveal any consistent abnormalities. A dopamine transporter radioligand has recently become available for clinical use, in single-photon emission computed tomography scanning, to assist in the evaluation of those with suspected PD. The scan is known as a DaTscan, and a recent analysis demonstrates that it does not provide greater accuracy than a clinical diagnosis based on history and examination of a patient [5].

Treatment

Initial

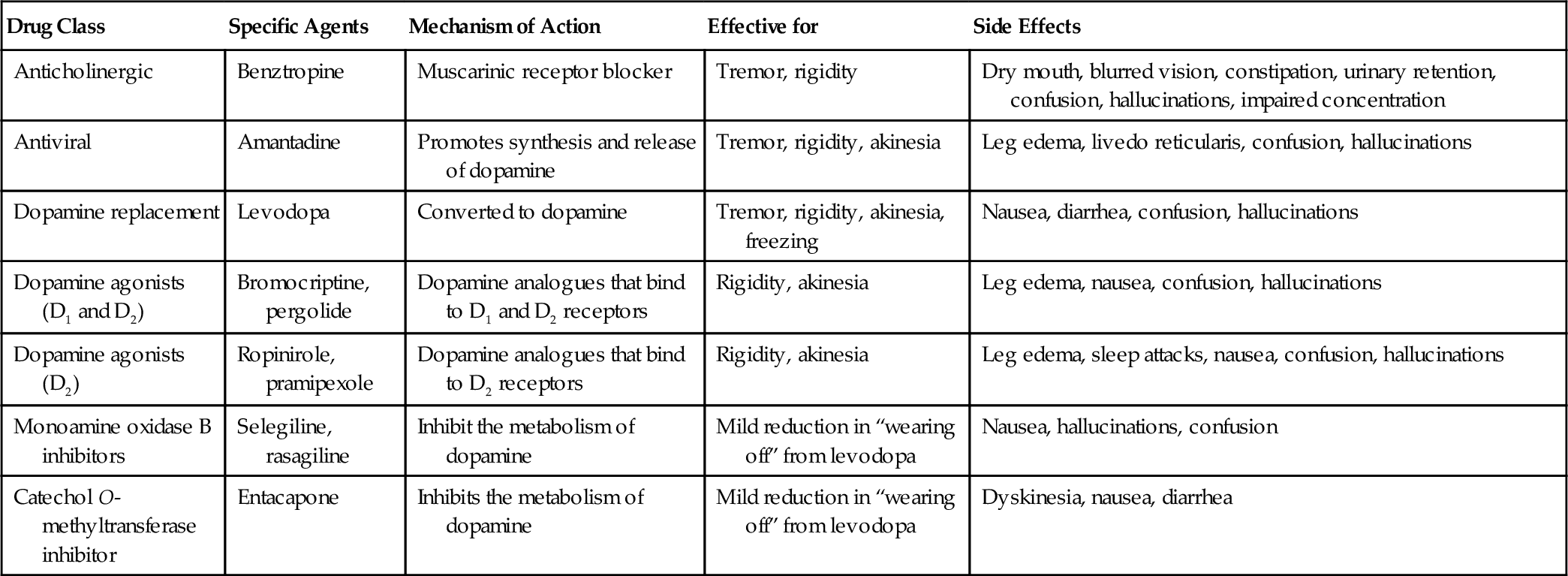

The decision to initiate medical treatment is based on the degree of disability and discomfort that the patient is experiencing. Six classes of drugs are used to treat PD (summarized in Table 141.1). The selection of a particular drug depends on the patient’s main complaint, which is usually either a rest tremor or bradykinesia. There is no evidence to suggest that expediting or delaying the onset of treatment for PD has any effect on the overall course of the disease. However, it is clear that those who do not receive treatment and are bradykinetic are at greater risk of falling and injuring themselves.

Anticholinergic agents are the oldest class of medications used in PD. They are most effective in reducing the rest tremor and rigidity associated with PD. However, the side effects associated with anticholinergic agents typically limit their usefulness. Amantadine is also used in the treatment of PD. Amantadine produces a limited improvement in akinesia, rigidity, and tremor.

Dopamine replacement remains the cornerstone of antiparkinson therapy. Levodopa is the natural precursor to dopamine and is converted to dopamine by the enzyme aromatic amino acid decarboxylase. To ensure that adequate levels of levodopa reach the central nervous system, levodopa is administered simultaneously with a peripheral decarboxylase inhibitor. In the United States, the most commonly used peripheral decarboxylase inhibitor is carbidopa. Levodopa is most effective in reducing tremor, rigidity, and akinesia. The most common side effects, seen with the onset of treatment, are nausea, abdominal cramping, and diarrhea. Long-term treatment with levodopa is associated with three types of complications: hourly fluctuations in motor state, dyskinesias, and a variety of psychiatric complaints including hallucinations and confusion. However, it is not clear whether the motor fluctuations are due to the levodopa treatment alone, the disease progression alone, or a complex interplay of imperfect dopamine replacement and the inexorable progression of disease. In summary, current evidence supports the use of dopamine replacement as soon as the symptoms of PD become troublesome to the individual patient. There is no evidence that supports withholding of treatment to minimize long-term motor complications.

Dopamine agonists, which directly stimulate dopamine receptors, are also used in the treatment of PD. These agents can be used either as an adjunct to levodopa therapy or as monotherapy. The older dopamine agonists, which are relatively nonspecific and exert their effects at both D1 and D2 receptors, are bromocriptine and pergolide. In comparison to the side effects seen with levodopa, there is a lower frequency of dyskinesias and a higher frequency of confusion and hallucinations. The newer dopamine agonists pramipexole and ropinirole are more specific for D2 receptors. These newer agents have been reported to cause daytime somnolence, peripheral edema, and impulse control disorders [6]. All dopamine agonists can cause orthostatic hypotension, particularly when they are first introduced. It is best to start with a small dose of medication at bedtime and then slowly increase the total daily dose.

Inhibitors of dopamine metabolism are also used in the medical treatment of PD. Both selegiline and rasagiline inhibit monoamine oxidase B, which metabolizes dopamine in the central nervous system. Thus, inhibitors of monoamine oxidase B are thought to improve an individual’s response to levodopa by alleviating the motor fluctuations that are seen with long-term levodopa treatment. Another agent that inhibits the metabolism of dopamine is entacapone. Entacapone inhibits catechol O-methyltransferase in the periphery. Entacapone is administered in conjunction with levodopa and, by inhibiting peripheral catechol O-methyltransferase activity, increases the amount of levodopa that reaches the central nervous system. The benefits of entacapone treatment include a reduction in total daily levodopa dose and an improvement in the length of time of maximum mobility [7].

Rehabilitation

The clinical pathologic process seen in PD reveals that patients tend to become more passive, less active, and less motivated as the disease progresses. The benefits to physical and occupational therapy are thus more far reaching than a simple improvement in motor function. The physical benefits include improvement in muscle strength and tone as well as maintenance of an adequate range of motion in the joints. The psychological benefits include enlistment of the patient as an active participant in treatment and provision of a sense of mastery over the effects of PD. Both physical therapy and occupational therapy focus on mobility, the use of adaptive equipment, and safety in both the home and community.

Because the symptoms of PD gradually worsen over time, individuals can benefit from periodic physical therapy training throughout the course of their illness. The training may take place through either community-based programs that are more readily accessible for those who live far from an academic center or home-based programs for those who cannot easily travel. An emphasis on gait training is particularly helpful to prevent falls and injury. Gait training typically involves training an individual to be conscious of taking a longer stride and putting the foot down with each step. Another method is to use visual cues to maintain a regular size for each step. For example, one can put strips of masking tape on the floor, at a regular interval that is comfortable for one’s height, weight, and gender. As PD progresses, episodes of frozen gait, in which the feet seem to be stuck to the floor, occur. Freezing episodes can be broken by multiple techniques, such as visualizing that one is stepping over an imaginary line on the floor, counting in a rhythmic cadence, or marching in place.

Occupational therapy is particularly helpful in recommending adaptive devices or establishing new routines that allow people with PD to continue to live independently. For example, the use of a long-handled shoehorn eliminates the need to bend over and thus reduces the risk that a person with PD will fall while getting dressed. Other examples of adaptive equipment are a firmly secured grab bar in the bathtub and a relatively high toilet seat with armrests to minimize the risk of freezing while on the toilet.

Speech therapy plays a critical role for those PD patients who suffer from communication difficulties. Although dysarthria is difficult to treat, hypophonia can be overcome with training. Specifically, the Lee Silverman Voice Treatment program has been shown to be effective in improving both the volume and clarity of speech in those with PD [8]. Swallow evaluation and therapy are also helpful in the treatment of dysphagia, which occurs as PD progresses.

Procedures

Feeding tubes are sometimes used in individuals who have severe end-stage PD. Some patients choose hospice care, without artificial feeding at that point. Individuals who do get feeding tubes may need to have medication doses adjusted (e.g., carbidopa/levodopa will now bypass the esophagus and have a shortened time to onset of action).

Surgery

Although a large number of medications are available for the treatment of early and moderately advanced PD, they are of limited efficacy in those with advanced PD. Several surgical procedures are currently available for those with advanced PD. These procedures consist of either creation of a permanent lesion or insertion of an electrical stimulator in a specific nucleus of the brain.

Thalamotomy consists of introduction of a lesion in the ventral intermediate nucleus of the thalamus. Thalamotomy has been reported to produce a reduction in tremor of the contralateral limb in 85% of the patients who were treated. Thalamotomy is recommended in PD patients with an asymmetric, severe, medically intractable tremor.

Unilateral pallidotomy consists of introduction of a lesion in the globus pallidus. The most striking benefits are a reduction in contralateral drug-induced dyskinesias, contralateral tremor, bradykinesia, and rigidity. Unilateral pallidotomy is recommended in PD patients with bradykinesia, rigidity, and tremor who experience significant drug-induced dyskinesia despite optimal medical therapy. However, data regarding the long-term cognitive effects of unilateral pallidotomy are limited and varied in their findings [9,10]. Thus neuropsychological evaluation is recommended in all patients both before and after surgery.

Deep brain stimulation (DBS) for PD consists of high-frequency electrical stimulation in either the globus pallidus or the subthalamic nucleus. DBS requires surgery, in which the source of electrical stimulation is placed subcutaneously in the chest wall and the leads to which it is attached are placed in one of the locations listed. The advantage of DBS is that the degree of electrical stimulation can be easily adjusted, externally, once the DBS unit is in place. In contrast, both thalamotomy and pallidotomy result in permanent, fixed lesions in the brain. DBS of the ventral intermediate nucleus of the thalamus is effective in the treatment of a severe and disabling tremor that is unresponsive to medical therapy, with reports of approximately 80% improvement in tremor 5 years after DBS implantation [11]. DBS of the globus pallidus results in a marked reduction in dyskinesia. There are also improvements in bradykinesia, speech, gait, rigidity, and tremor. DBS of the subthalamic nucleus also results in marked improvement in tremor, akinesia, gait, and postural stability [12].

Potential Disease Complications

Depression is found in approximately 35% of those with PD [13]. It may be difficult to distinguish true depression from the apathy associated with PD. The crucial factor is to determine whether the patient has a true disturbance of mood, with loss of interest, sleep disturbance, and sometimes suicidal thoughts. The reasons for depression in PD are a subject of debate. There is a suspicion that the pathologic process of PD itself may predispose to depression. Regardless of the cause, recognition and treatment of depression may have a significant impact on the overall disability caused by the illness. Many PD patients have been treated safely and effectively with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, such as fluoxetine and paroxetine. Tricyclic antidepressants can be used, although their anticholinergic properties may limit their effectiveness.

Gastrointestinal complications also occur in PD. Dysphagia is typically due to poor control of the muscles of both mastication and the oropharynx. Soft food is easier to eat, and antiparkinson medication improves swallowing. Constipation is a frequent complaint in those with PD. Treatment includes increase in physical activity; discontinuation of anticholinergic drugs; and maintenance of a diet with intake of adequate fluids, fruit, vegetables, fiber, and lactulose (10 to 20 g daily).

Potential Treatment Complications

The motor complications seen with pharmacologic treatment are divided into two categories: fluctuations (off state) and levodopa-induced dyskinesias. The off state consists of a return of the signs and symptoms of PD: bradykinesia, tremor, and rigidity. Patients may also experience anxiety, dysphoria, or panic during an off state.

The development of levodopa-induced dyskinesias appears to be related to the degree of dopamine receptor supersensitivity. As PD progresses, there is an increasing loss of dopamine receptors. This results in an increased sensitivity of the remaining dopamine receptors to dopamine itself. Thus, there is a greater chance for development of dyskinesias at a given dose of levodopa. Treatment options are to lower each dose of levodopa but with an increase in the frequency with which it is taken; to add or to increase the dose of a dopamine agonist while the dose of levodopa is decreased; and to add amantadine, which has been shown to be an antidyskinetic agent in some patients [14]. There are potential complications to each of these solutions: reducing each dose of levodopa while increasing the frequency of doses (e.g., once every 2 hours) is a difficult schedule for a patient to maintain; adding or increasing the dose of dopamine agonist may result in compulsive behaviors (shopping, gambling, hypersexuality), excessive daytime sleepiness, and peripheral edema; and amantadine may cause confusion. An alternative is to treat those who continue to experience an improvement in their mobility with levodopa but develop dyskinesias that become more pronounced as the day progresses with DBS.