CHAPTER 14 Local Anesthetics

2 How are local anesthetics classified?

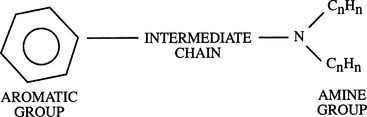

Aminoesters: Esters are local anesthetics the intermediate chain of which forms an ester link between the aromatic and amine groups. Commonly used ester local anesthetics include procaine, chloroprocaine, cocaine, and tetracaine (Figure 14-1).

Aminoesters: Esters are local anesthetics the intermediate chain of which forms an ester link between the aromatic and amine groups. Commonly used ester local anesthetics include procaine, chloroprocaine, cocaine, and tetracaine (Figure 14-1).5 What is the mechanism of action of local anesthetics?

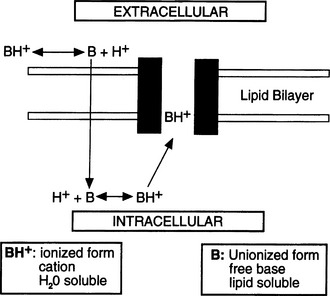

The cascade of events (Figure 14-2) follows:

6 Your patient states that he was told he is allergic to Novocain, which he received for a tooth extraction. Should you avoid using local anesthetics in this patient?

7 What determines local anesthetic potency?

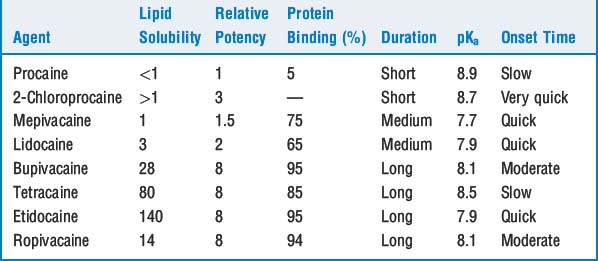

The higher the solubility, the greater the potency (Table 14-1). This relationship is more clearly seen in isolated nerve than in clinical situations when factors such as vasodilation and tissue redistribution response to various local anesthetics influence the duration of local anesthetic effect. For example, high lipid solubility of etidocaine results in profound nerve blockade in isolated nerve. Yet, in clinical epidural use etidocaine is considerably sequestered in epidural fat, leaving a reduced amount of etidocaine available for neural blockade.

12 Which regional anesthetic blocks are associated with the greatest degree of systemic vascular absorption of local anesthetic?

13 Why are epinephrine and phenylephrine often added to local anesthetics? What cautions are advisable regarding the use of these drugs?

These drugs cause local tissue vasoconstriction, limiting uptake of the local anesthetic into the vasculature and thus prolonging its effects and reducing its toxic potential (see Question 14). Epinephrine, usually in 1:200,000 concentration, is also a useful marker of inadvertent intravascular injection. Epinephrine is contraindicated for digital blocks or other areas with poor collateral circulation. Systemic absorption of epinephrine may also cause hypertension and cardiac dysrhythmias, and caution is advised in patients with ischemic heart disease, hypertension, preeclampsia, and other conditions in which such responses may be undesirable.

14 How does a patient become toxic from local anesthetics? What are the clinical manifestations of local anesthetic toxicity?

15 Is the risk of cardiotoxicity the same with various local anesthetics?

The ratio of the dosage required for irreversible cardiovascular collapse and the dosage that produces CNS toxicity is much lower for bupivacaine and etidocaine than for lidocaine.

The ratio of the dosage required for irreversible cardiovascular collapse and the dosage that produces CNS toxicity is much lower for bupivacaine and etidocaine than for lidocaine. Cardiac resuscitation is more difficult following bupivacaine-induced cardiovascular collapse. It may be related to the lipid solubility of bupivacaine, which results in slow dissociation of this drug from cardiac sodium channels (fast-in, slow-out). By contrast, recovery from less lipid-soluble lidocaine is rapid (fast-in, fast-out).

Cardiac resuscitation is more difficult following bupivacaine-induced cardiovascular collapse. It may be related to the lipid solubility of bupivacaine, which results in slow dissociation of this drug from cardiac sodium channels (fast-in, slow-out). By contrast, recovery from less lipid-soluble lidocaine is rapid (fast-in, fast-out).KEY POINTS: Local Anesthetics

16 How will you prevent and treat systemic toxicity?

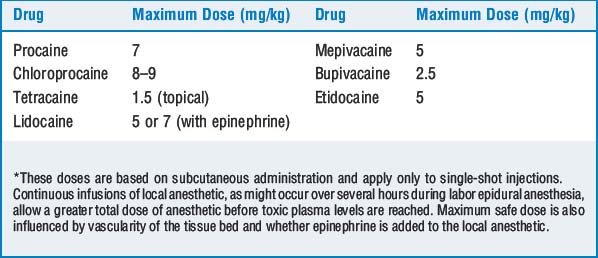

Most reactions can be prevented by careful selection of dose and concentration, use of test dose with epinephrine, incremental injection with frequent aspiration, monitoring patient for signs of intravascular injection, and judicious use of benzodiazepine to raise the seizure threshold.

Most reactions can be prevented by careful selection of dose and concentration, use of test dose with epinephrine, incremental injection with frequent aspiration, monitoring patient for signs of intravascular injection, and judicious use of benzodiazepine to raise the seizure threshold. Seizures can quickly lead to hypoxia and acidosis, and acidosis worsens the toxic effects. A patent airway and adequate ventilation with 100% oxygen should be ensured.

Seizures can quickly lead to hypoxia and acidosis, and acidosis worsens the toxic effects. A patent airway and adequate ventilation with 100% oxygen should be ensured. If seizures develop, small doses of intravenous diazepam (0.1 mg/kg) or thiopental (1 to 2 mg/kg) may terminate the seizure. Short-acting muscle relaxants may be indicated for ongoing muscle activity or to facilitate intubation if necessary.

If seizures develop, small doses of intravenous diazepam (0.1 mg/kg) or thiopental (1 to 2 mg/kg) may terminate the seizure. Short-acting muscle relaxants may be indicated for ongoing muscle activity or to facilitate intubation if necessary. Cardiovascular collapse with refractory ventricular fibrillation following local anesthetics, particularly bupivacaine, can be extremely difficult to resuscitate. Treatment includes sustained cardiopulmonary resuscitation, repeated cardioversion, high doses of epinephrine, and use of bretylium to treat ventricular dysrhythmias. Intravenous intralipid has been used successfully in cases in which conventional resuscitation measures were unsuccessful. Suggested dose is initial bolus of 1.5 ml/kg of 20% intralipid solution, which can be repeated every 3 to 5 minutes up to a total maximum dose of 8 ml/kg.

Cardiovascular collapse with refractory ventricular fibrillation following local anesthetics, particularly bupivacaine, can be extremely difficult to resuscitate. Treatment includes sustained cardiopulmonary resuscitation, repeated cardioversion, high doses of epinephrine, and use of bretylium to treat ventricular dysrhythmias. Intravenous intralipid has been used successfully in cases in which conventional resuscitation measures were unsuccessful. Suggested dose is initial bolus of 1.5 ml/kg of 20% intralipid solution, which can be repeated every 3 to 5 minutes up to a total maximum dose of 8 ml/kg.17 What is the risk of neurotoxicity with local anesthetics?

Transient neurologic symptoms manifest in the form of moderate-to-severe pain in the lower back, buttocks, and posterior thighs. These symptoms appear within 24 hours of spinal anesthesia and generally resolve within 7 days. The delayed onset may reflect an inflammatory etiology for these symptoms. They are seen most commonly with lidocaine spinal anesthesia and are rare with bupivacaine. Patients having surgery in the lithotomy position appear to be at increased risk of neurologic symptoms following either spinal or epidural anesthesia.

Transient neurologic symptoms manifest in the form of moderate-to-severe pain in the lower back, buttocks, and posterior thighs. These symptoms appear within 24 hours of spinal anesthesia and generally resolve within 7 days. The delayed onset may reflect an inflammatory etiology for these symptoms. They are seen most commonly with lidocaine spinal anesthesia and are rare with bupivacaine. Patients having surgery in the lithotomy position appear to be at increased risk of neurologic symptoms following either spinal or epidural anesthesia. Cauda equina syndrome: A few cases of diffuse injury to the lumbosacral plexus were initially reported in patients receiving continuous spinal anesthesia with 5% lidocaine dosed via microcatheters. The mechanism of neural injury is thought to be that nonhomogeneous distribution of spinally injected local anesthetic may expose sacral nerve roots to a high concentration of local anesthetic with consequent toxicity. Rare cases in the absence of microcatheters have also been described. Avoid injecting large amounts of local anesthetic in the subarachnoid space, especially if less than an anticipated response is obtained with the initial dose.

Cauda equina syndrome: A few cases of diffuse injury to the lumbosacral plexus were initially reported in patients receiving continuous spinal anesthesia with 5% lidocaine dosed via microcatheters. The mechanism of neural injury is thought to be that nonhomogeneous distribution of spinally injected local anesthetic may expose sacral nerve roots to a high concentration of local anesthetic with consequent toxicity. Rare cases in the absence of microcatheters have also been described. Avoid injecting large amounts of local anesthetic in the subarachnoid space, especially if less than an anticipated response is obtained with the initial dose.1. Mulroy M.E. Systemic toxicity and cardiotoxicity from local anesthetics: incidence and preventive measures. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2002;27:556-561.

2. Rosenblatt M.A., Abel M. Successful use of a 20% lipid emulsion to resuscitate a patient after a presumed bupivacaine-related cardiac arrest. Anesthesiology. 2006;105:217-218.

3. Strichartz G.R., Berde C.B. Local anesthetics. In: Miller R.D., editor. Anesthesia. ed 6. Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone; 2005:573-603.