CHAPTER 14 Group Psychotherapy

OVERVIEW

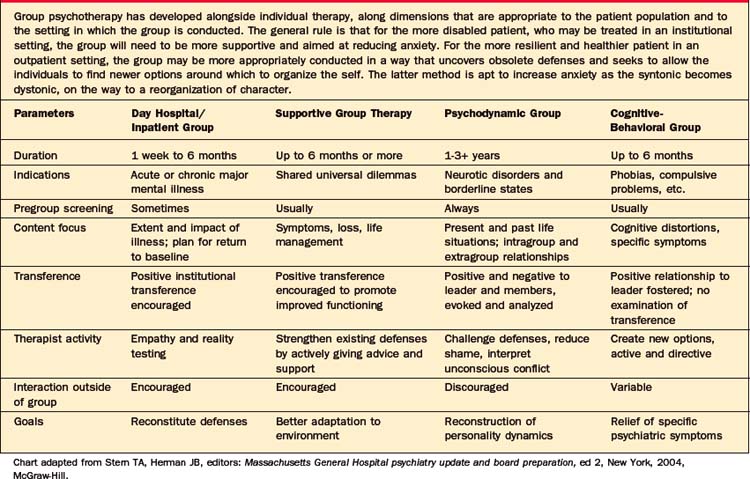

A therapy group is a collection of patients who are selected and brought together by the leader for a shared therapeutic goal (Table 14-1). In this chapter some of the goals of a therapy group will be described, and a therapy group will be distinguished from a therapeutic group enterprise. Group therapy rests on some common assumptions that apply to the entire panoply of therapeutic groups. Since the time that the field of psychoanalysis moved from an exploration of one’s inner psyche to an understanding of the importance of the intimate relationship between infant and child, and later between adults, we have been aware that the need for other people resides in all human beings. The need for attachment is seen as primary by a whole host of group theorists; the press for belonging is that which yields a sense of cohesion that can help the individual stay with the anxious new moments in a group of strangers. For better and for worse, people who wish to belong to a cohesive community are apt to mimic and to identify with the feelings and beliefs of other members in that community. Adages such as “birds of a feather fly together” emphasize that we tend to mimic the people around us in order to belong. At its best, this process allows for new interpersonal learning; at its worst, it raises the specter of dangerous mobs. People in distress tend to downplay and to mute their concerns to avoid facing their problems. In a group, each member is exposed to feelings, to needs, and to drives that increase the individual’s awareness of his or her own passions. Knowledge is power, and the power to change requires a deeper knowledge of one’s blind spots. There is an inevitable pull (based on the contagion and amplification that often overrides the normal shyness of anyone in a crowd of strangers) to get to know others more intimately in a group. As the members of a cohesive group move away from being strangers and get to know each other more deeply, they experience their own approaches to intimacy with others and with the self; in exchange, they receive immediate feedback on the impact they have on important others in their surroundings.

Many efforts have been made to describe the curative factors in a therapy group. Summed up into the essential elements, groups help people change and grow by allowing the individual within the group to grow and develop beyond the constrictions in life that brought that person into treatment. While some group theorists have relied on a cluster of factors relevant to their models of the mind and of pathology, all have used some of the whole group of therapeutic factors identified in Table 14-2. The more common healing factors are those that act by reducing each individual’s isolation, by diminishing shame (which we have come to recognize as a major pathogenic factor in mental illness), and by evoking memories of early familial attitudes and interactions (that now can be approached differently with a new set of options and in the context of support). Another healing factor is expanding one’s sublimatory options. The impulses that flourished in the context of childhood-limited defenses can now be checked by a broader emotional and behavioral repertoire that can be practiced among group members in the here and now. Provision of support and empathic confrontation can be curative as well. People often fear groups because they imagine they will be the target of harsh confrontation; they are unaware that the cohesive group is a marvelous source of concern and problem solving. Last, unmourned losses are often at the root of a melancholic and depressive stance. Listening to others grieve and responding to others’ awareness of our own losses can free an individual to move on.

Table 14-2 Yalom’s Therapeutic Factors in Group Psychotherapy

| There are many attempts to categorize what is effective in group therapy. Some factors will be more or less active depending on the kind of group. For example, corrective familial experience will figure prominently in psychodynamic groups, whereas cognitive-behavioral groups will emphasize learning and reality testing. Some are universal to all groups, such as the following: |

| Factor | Definition |

|---|---|

| Acceptance | The feeling of being accepted by other members of the group. Differences of opinion are tolerated, and there is an absence of censure. |

| Altruism | The act of one member helping another; putting another person’s need before one’s own and learning that there is value in giving to others. The term was originated by Auguste Comte (1798–1857), and Freud believed it was a major factor in establishing group cohesion and community feeling. |

| Cohesion | The sense that the group is working together toward a common goal; also referred to as a sense of “weness.” It is believed to be the most important factor related to positive therapeutic effects. |

| Contagion | The process in which the expression of emotion by one member stimulates the awareness of a similar emotion in another member. |

| Corrective familial experience | The group re-creates the family of origin for some members who can work through original conflicts psychologically through group interaction (e.g., sibling rivalry, or anger toward parents). |

| Empathy | A capacity of a group member to put himself or herself into the psychological frame of reference of another group member and thereby understand his or her thinking, feeling, or behavior. |

| Imitation | The conclusion of emulation or modeling of one’s behavior after that of another (also called role modeling); it is also known as spectator therapy, as one patient learns from another. |

| Insight | Conscious awareness and understanding of one’s own psychodynamics and symptoms of maladaptive behavior. Most therapists distinguish two types: (1) intellectual insight—knowledge and awareness without any changes in maladaptive behavior; (2) emotional insight—awareness and understanding leading to positive changes in personality and behavior. |

| Inspiration | The process of imparting a sense of optimism to group members; the ability to recognize that one has the capacity to overcome problems; it is also known as instillation of hope. |

| Interpretation | The process during which the group leader formulates the meaning or significance of a patient’s resistance, defenses, and symbols; the result is that the patient develops a cognitive framework within which to understand his or her behavior. |

| Learning | Patients acquire knowledge about new areas, such as social skills and sexual behavior; they receive advice, obtain guidance, attempt to influence, and are influenced by other group members. |

| Reality testing | Ability of the person to evaluate objectively the world outside the self; this includes the capacity to perceive oneself and other group members accurately. |

| Ventilation | The expression of suppressed feelings, ideas, or events to other group members; sharing of personal secrets ameliorates a sense of sin or guilt (also referred to as self-disclosure). |

Adapted from Yalom ID: Theory and practice of group psychotherapy, ed 5, New York, 2005, Basic Books.

Since Dr. Pratt first offered his “classes” for tubercular patients at the Massachusetts General Hospital in 1905, people have come together to commiserate with one another around common problems, to share information, and to learn how to deal with the impact of those problems on their lives. These groups are often referred to as “symptom specific” or “population specific.” Groups have been organized around medical illnesses (e.g., cancer, diabetes, and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome [AIDS]), around psychological problems (e.g., bereavement), and around psychosocial sequelae of trauma (e.g., war or natural disasters). The goals of such groups are to provide support and information that are embedded in a socially accepting environment with people who are in a position to understand what the others are going through. The treatment may emerge from cognitive-behavioral principles, from psychodynamic principles, or from psychoeducational ones. Frequently, these groups tend to be time limited; members often join at the same time and terminate together. The problems addressed in these groups are found in a broad variety of patients, from the very healthy to the more distressed, and they cut across other demographic variables (e.g., age and culture). Increasingly, research data have shown that involvement in these groups can extend the survival and the quality of life of the severely ill (e.g., women with end-stage breast cancer).

Group therapy is the treatment of choice for people with chronic and habitual ways of dealing with life, even when those ways run counter to the patients’ best interest. Character difficulties are tenacious for all human beings, from the healthiest neurotic to the most regressed patient. Characterological problems often occur outside of the patient’s awareness (often to the disbelief and the alarm of others who see the problems clearly). Such problems are syntonic and perceived as “Who I am” when brought into awareness. Like all bad habits, such ingrained behaviors are resistant to change, even when the patient wants to make such a change. When these characterological stances occur in the group, they are often repeated and come to the attention of the other members, who respond by confrontation and with offers of alternative strategies. In current parlance the term neurotic implies a relatively healthy individual who contains conflict, who owns some of the responsibility, and who may be nonetheless conflicted and guilty about his or her own life for reasons having to do with early developmental realities. In a psychodynamic open-ended group therapy, the neurotic patient observes resistance to intimacy and ambition, and works within the multiple transferences to develop a freer access to life’s options.

CREATING A GROUP

Before approaching the concrete work of planning and organizing a psychotherapy group, the goals of the group must be clearly understood and be developed by the leader. These goals in turn will be dependent on the setting, the population, the time available for treatment, and the training and capacity of the leader(s). The group agreements, or contract, will be dictated by the goals.

CLINICAL VIGNETTE

Creation and Goals of a Psychodynamic Group

Dr. B. excluded two patients. The first patient was severely depressed and had frequent suicidal thoughts that were often triggered by interpersonal conflict. When she understood that there would be relatively little structure in the group and that many feelings would get stirred up by relating to group members, she was not sure that she could be safe. It was thought that she needed to work with her individual therapist further until she was better able to deal with conflict in a safe manner. The second excluded patient was a woman with depression and an eating disorder who was looking for skills to help her control urges to binge and to purge. Dr. B. and the patient agreed that this group would not be able to provide this for her, and she was referred to a cognitive-behavioral therapy group for women with eating disorders. Finally, he had four women and two men who agreed to join the group. All had depression, anxiety, or both, and all wanted to work on their interpersonal style and their relationships.

An example of the process of a psychodynamic group follows.

In a therapy group, as in any therapeutic work, the leader must remain as pure as Caesar’s wife; dual roles are unacceptable, and no overly familiar incursions into the members’ personal lives, nor theirs of the leader, are tolerated. No special fee arrangements that are not in the awareness of the group can be tolerated without damaging the integrity of the group’s boundaries. If matters arise in the group that are of a nature to threaten the confidentiality of extragroup relationships, they may need to be conducted apart from the group, but the group should know this is happening. This refusal to hold secret any extragroup contacts sets a fine model that says the group is a safe therapeutic agent. Most important, the leader must acknowledge errors and strive to avoid them in the future. This became clear in our vignette about Dr. B.

COMBINED THERAPIES

It is crucial that the two therapists collaborate (by frequent phone calls, and by avoiding the patients’ attempts to split them). In the case where the two therapists do not agree, or do not respect the other’s work, the patient is potentially at great risk of harm, or at least in a stalemate that is iatrogenic in origin. It is impossible to overstate the importance of using supervisors and consultants when such a mismatch occurs.

RESEARCH, OUTCOME, AND EVALUATION

Research instruments are useful for measuring patient satisfaction and self-reports of increased well-being. The Clinical Outcome Results battery developed by the American Group Psychotherapy Association is one example; it uses such measures as the Symptom Checklist 90—Revised (SCL-90R), the Social Adjustment Scale Self Report (SAS-SR), the Multiple Affect Adjective Check List—Revised (MAACL-R), and the Global Assessment Scale (GAS). More recently, measures such as the Structured Analysis of Social Behavior and the Group Climate Questionnaire (GCQ) have been used extensively by MacKenzie and others who work with patients in structured time-limited groups.

Alonso A. Group psychotherapy. In Stern TA, Herman JB, editors: Massachusetts General Hospital psychiatry update and board preparation, ed 2, New York: McGraw-Hill, 2004.

Alonso A, Swiller HI, editors. Group therapy in clinical practice. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press, 1993.

Bion WR. Experiences in groups. London: Tavistock, 1961.

Bloch S, Crouch E. Therapeutic factors in group psychotherapy. New York: Oxford University Press, 1985.

Brabender V, Fallon A. Models of inpatient group psychotherapy. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press, 1993.

Durkin H. The group in depth. New York: International Universities Press, 1964.

Ezriel H. Psychoanalytic group therapy. In: Wolberg LR, Schwartz EK, editors. Group therapy: 1973. An overview. New York: Intercontinental Medical Book Corp, 1973.

Foulkes SH. Group process and the individual in the therapeutic group. Br J Med Psychol. 1961;34:23-31.

Freud S. Group psychology and analysis of the ego. In Standard edition of the complete psychological works of Sigmund Freud. London: Hogarth; 1962.

Gans JS. Broaching and exploring the question of combined group and individual therapy. Int J Group Psychother. 1990;40:123-137.

Glatzer H. The working alliance in analytic group psychotherapy. Int J Group Psychother. 1978;28:147-154.

Kaplan HI, Sadock BJ, editors. Comprehensive group psychotherapy, ed 3, Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins, 1999.

Kauff P. The contribution of analytic group therapy to the psychoanalytic process. In: Alonso A, Swiller H, editors. Group therapy in clinical practice. Washington, DC: APPI, 1993.

Kelly JA, Murphy DA, Bahr GR, et al. Outcome of cognitive-behavioral and support group brief therapies for depressed, HIV-infected persons. Am J Psychiatry. 1993;150:1679.

Klein RH, Bernard HS, Singer DL, editors. Handbook of contemporary group psychotherapy. Madison, CT: International Universities Press, 1992.

Leszcz M. The interpersonal approach to group psychotherapy. Int J Group Psychother. 1992;42:37-62.

MacKenzie KR, editor. Classics in group psychotherapy. New York: Guilford Press, 1992.

MacKenzie KR. Time-managed group psychotherapy. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press, 1997.

Malan DH, Balfour FHG, Hood VG, Shooter AMN. Group psychotherapy: a long-term follow-up study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1976;33:1303-1315.

Motherwell L, Shay J. Complex dilemmas in group therapy. New York: Brunner Routledge, 2005.

O’Leary JV. The postmodern turn in group therapy. Int J Group Psychother. 2002;51(4):473-487.

Pam A, Kemper S. The captive group: guidelines for group thera-pists in the inpatient setting. Int J Group Psychother. 1993;43:419-438.

Riess H. Integrative time-limited group therapy for bulimia nervosa. Int J Group Psychother. 2002;52:1-26.

Riester AE, Kraft IA, editors. Child group psychotherapy. Madison, CT: International Universities Press, 1986.

Rutan JS, Stone WS, editors. Psychodynamic group psychotherapy. New York: Guilford Press, 1993.

Scheidlinger S. On the concept of “mother-group,”. Int J Group Psychother. 1974;24:417-428.

Spiegel D, Bloom JR, Kraemer HC, et al. Effect of psychosocial treatment on survival of patients with metastatic breast cancer. Lancet. 1989;2(8668):888-891.

Yalom ID. The theory and practice of group psychotherapy, ed 4. New York: Basic Books, 1995.

Yalom ID. Theory and practice of group psychotherapy, ed 5. New York: Basic Books, 2005.